Stress Among New Oncology Nurses

New oncology nurses face multiple stressors related to the predicted nursing shortage, demanding work responsibilities, and growing complexity of cancer care. The confluence of these stressors often causes new nurses to leave their profession. The loss of new nurses leads to staffing, economic, and safety concerns, which have a significant impact on the quality of oncology nursing care.

At a Glance

- Oncology nurses are valuable resources in the healthcare system.

- A promising source of support identified by new oncology nurses is the use of a nurse educator coach to guide them on how to integrate self-care strategies into daily practice.

-

The findings from the current study can be used to develop innovative interventions to achieve optimal job satisfaction, retention rates, and professional experience for new oncology nurses.

Jump to a section

Oncology nursing has been described as one of the most stressful specialty areas (Lederberg, 1989). Several studies have demonstrated that providing care for patients with cancer is a stressful occupation for nurses (Campos de Carvalho, Muller, Bachion de Carvalho, & de Souza Melo, 2005; Isikhan, Comez, & Danis, 2004). Work-related stress has a significant impact on the oncology nursing workforce. The oncology field is a complex environment in which to work because it requires nurses who are educated, skilled, and clinically competent to care for patients with cancer. Nurses also support their families through the treatment process and, perhaps, dying and death as well (Kravits, McAllister-Black, Grant, & Kirk, 2010). The factors, levels, response to, and consequences of stress on the professional and personal well-being of the oncology nurse has been the focus of a growing body of research. Factors causing stress in oncology nurses are associated with the growing shortage of nurses, characteristics of the work environment, and conflicting feelings of working with patients (Engel, 2004; McVicar, 2003). The purpose of this article is to examine the experience, sources of stress, and preferences for self-management or educational programs reported by new oncology nurses when transitioning into the oncology work environment.

Methods

This study used the survey research method. The protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review committee at Daemen College in Amherst, NY. Data were collected during the spring of 2013. Participants were recruited from a large cancer center in New York state, which gave approval prior to the recruitment of participants, and used a convenience sample of 42 oncology nurses who were aged 18 years or older, able to read and write English, assigned to direct patient care, willing to complete the survey, and had less than three years’ experience in the oncology field. The participants used SurveyMonkey® to respond and were assured of confidentiality.

A questionnaire packet and a standardized interview guide were used for this study. The packet consisted of a five-part questionnaire that contained (a) demographic questions, (b) the Nurse Stress Scale (NSS) (Gray-Toft & Anderson, 1981), (c) an instrument measuring coping strategies used by nurses (US1), (d) questions asking about the types of coping strategies that nurse educators could use to help teach nurses how to cope with stress, and (e) open-ended questions that were used to understand new oncology nurses’ perception of stress and suggest possible coping strategies for stressful situations.

Findings

The first part was the respondents’ background characteristics, which showed that 42 nurses completed the survey, 39 were female, and 32 ranged in age from 21–36 years. Regarding work experience, 20 of the nurses reported working one year or less. Twenty-three nurses reported that they were not thinking about leaving their job, whereas 19 nurses were thinking about leaving their job.

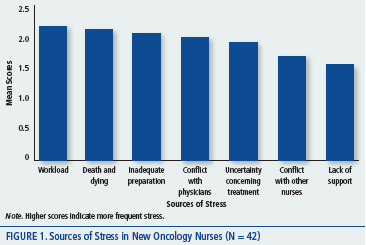

The second part of the study identified the frequency with which new oncology nurses working in a hospital experienced stress in the performance of their duties, as measured using the NSS (Gray-Toft & Anderson, 1981). Figure 1 summarizes the mean scores for the most frequent stress factors reported by the nurses. The factors were workload, death and dying, inadequate preparation, conflict with physicians, uncertainty concerning treatment, conflict with other nurses, and lack of support.

No significant association was noted between age and level of stress as reflected by the NSS. However, nurses with higher stress levels were more likely to think about leaving their current work. Nurses who answered “yes” regarding intent to leave registered higher stress (X = 2.14, SD = 0.28) than those who answered “no” (X = 1.89, SD = 0.314). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.013).

The four most frequently used coping behaviors identified were sleeping, drinking coffee, developing a personal perspective about the value of the work, and participating in entertaining activities and eating. No significant associations were noted among age, work experience, nurses’ thoughts about leaving their current job, and use of coping behaviors among new oncology nurses. Independent samples, t-tests, and one-way analysis of variance tests were used to assess the differences of stress, coping behaviors, and coping strategies by age, gender, and years of experience. No significant associations were noted among age (p = 0.055), work experience (p = 0.191), nurses’ intent to leave their current job (p = 0.109), and use of coping behaviors among new oncology nurses.

Another area of interest was to identify coping strategies that nurse educators can use to help new oncology nurses handle the stress. Among the eight coping strategies, “hearing motivational words,” “hearing words of appreciation,” and “getting emotional support from my manager” were reported as the most preferred coping strategies, whereas “having an opportunity to participate in continuing education” and “keeping the same clinical instructor during the entire orientation period” were the least favored for coping with stress.

Responses indicated that the most stressful aspect of nurses’ work clustered around three categories: the nature of the patients, insufficient education and training programs, and conflict in the work environment. Other coping behaviors nurses used to deal with their stress included praying, listening to music, taking medication, and talking with other new nurses or friends. Nurses also reported needing a supportive work environment as well as more support from their supervisor. One interesting intervention suggested was the use of a nurse educator coach to provide support, guidance, and education during the transition period.

Discussion and Implications

Work-related stress has a significant impact on the oncology nursing workforce. Stress experienced by the new oncology nurse affects their job satisfaction, desire to stay in nursing and, most important, physical and psychological health. The authors’ findings are consistent with other empirical research (Alacacioglu, Yavuzsen, Dirioz, Oztop, & Yilmaz, 2009; Rodrigues & Chaves, 2008). The authors found that the most stressful factors for new oncology nurses were the unpredictable workload, dealing with death and dying, and inadequate preparation for their job. Similar findings were reported in a robust literature review suggesting nurses who reported various frustrations did not experience a nurturing work environment (McVicar, 2003). Some researchers have reported that a supportive work environment for new oncology nurses significantly contributed to better job satisfaction and less stress (Greco, Laschinger, & Wong, 2006; McVicar, 2003). Current findings suggest effective interventions are needed to support nursing practice, job satisfaction, and patient safety in the delivery of cancer nursing care by novice nurses.

These findings have implications for nurse educators, managers, and executive leadership in developing education programs and stress management interventions for new oncology nurses. For example, educational programs can educate new nurses on ways to adapt to their new roles, communicate their needs, and establish realistic professional growth goals. Educational programs could also teach self-management techniques to reduce high stress levels. Younger nurses (aged 35 years or younger) reported using coping behaviors more often than older respondents. Younger nurses also preferred to have those strategies taught by the nurse educators. Preferences such as these can be integrated into programs focusing on generational differences and their impact on the work environment. In addition, new oncology nurses indicated the need for stronger support and more resources from managers and organizational leadership. This information can be used to create tailored didactic and clinical programs specific to new oncology nurses.

Conclusion

As new nurses enter the workforce, identifying methods that will prepare them for the delivery of safe and high-quality oncology care is critical. Because oncology nursing is stressful, methods should be identified that will reduce the high level of stress. The current article identifies factors causing stress in new oncology nurses and coping behaviors preferred by this group of nurses. The findings regarding the coping behaviors and strategies can be used in future orientation or continuing education programs to initiate discussions with novice nurses about work-related stress and strategies that can manage stress. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health report also recommended the use of nurse residency programs to help nurses adapt to their new roles and reduce first-year turnover rate (Institute of Medicine, 2010). The current nursing shortage and high turnover rates threaten the safety and quality of patient care (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2014); therefore, healthcare organizations must recognize the critical need to provide a supportive environment and additional training for new nurses to achieve a long and successful oncology nursing career.

References

Alacacioglu, A., Yavuzsen, T., Dirioz, M., Oztop, I., & Yilmaz, U. (2009). Burnout in nurses and physicians working at an oncology department. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 543–548. doi:10.1002/pon.1432

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2014). Nursing shortage. Retrieved from http://aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage

Campos de Carvalho, E., Muller, M., Bachion de Carvalho, P., & de Souza Melo, A. (2005). Stress in the professional practice of oncology nurses. Cancer Nursing, 28, 187–192.

Engel, B. (2004). Are we out of our minds with nursing stress? Creative Nursing, 10, 4–6.

Gray-Toft, P., & Anderson, J.G. (1981). Stress among hospital nursing staff: Its causes and effects. Social Science Medicine, 15A, 639–647.

Greco, P., Laschinger, H.K., & Wong, C., (2006). Leader empowering behaviors, staff nurse empowerment, and work engagement/burnout. Nursing Leadership, 19, 41–56. doi:10.12927/cjnl.2006.18599

Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Isikhan, V., Comez, T., & Danis, M. (2004). Job stress and coping strategies in health care professionals working with cancer patients. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8, 234–244.

Kravits, K., McAllister-Black, R., Grant, M., & Kirk, C. (2010). Self-care strategies for nurses: A psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Applied Nursing Research, 23, 130–138. doi:10.1016/j .apnr.2008.08.002

Lederberg, M. (1989). Psychological problems of staff and their management. In J.C. Holland & J. Rowland (Eds.), Handbook of psycho-oncology (pp. 631–646). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

McVicar, A. (2003). Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44, 633–642. doi:10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02853.x

Rodrigues, A., & Chaves, E. (2008). Stressing factors and coping strategies used by oncology nurses. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 16, 24–28. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692008000100004

About the Author(s)

Rowida Mohammed Naholi, MSN, RN, is an oncology clinical instructor at the King Fahed Specialist Hospital in Dammam, Saudi Arabia; Cheryl L. Nosek, DNS, RN, CNE, is an associate professor in the Division of Health and Human Services at Daemen College in Amherst, NY; and Darryl Somayaji, PhD, RN, CNS, CCRC, is a postdoctoral research fellow in cancer and health disparities at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston, MA. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The authors did not receive honoraria for this work. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the authors or editorial staff. Naholi can be reached at rowida.naholi@daemen .edu, with copy to editor at CJONEditor@ons.org.