Evaluation of Employee Vaccination Policies in Outpatient Oncology Clinics: A Pilot Study

Background: All major hospital facilities in the state of Utah have employee vaccination policies. However, the presence of healthcare worker vaccination policies in outpatient oncology clinics was unknown.

Objectives: The objectives of this article are to identify oncology outpatient employee vaccination policies in Utah and to identify what consequences, if any, are present for unvaccinated employees.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study design in which clinic managers from outpatient oncology clinics were asked, via questionnaire, to describe the clinic’s employee vaccination policy and the consequences for refusing the policy.

Findings: Most vaccination policies applied to employees primarily assigned to work in the direct patient care area. Most commonly, influenza and hepatitis B vaccines were required as part of the vaccination policy. Most managers offered free vaccinations to employees, but most managers also allowed employees to refuse to follow the vaccination policy for medical, religious, or personal reasons.

Jump to a section

Vaccines are one of the most important public health achievements of all time (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). Recommended by CDC (2013b), vaccines are an efficacious and cost-effective strategy for reducing healthcare costs associated with communicable illness. However, despite the success of vaccines in reducing vaccine-preventable diseases and, in some cases, eradicating disease, vaccination rates remain suboptimal in some communities in the United States (CDC, 2012b; Williams et al., 2014).

Although vaccines are commonly associated with childhood, the need for and importance of vaccinations continues into adulthood (CDC, 2012a). Adults employed as healthcare workers (HCWs) are at an increased risk for spreading vaccine-preventable diseases to at-risk populations because of physical contact during patient care. As a result, it is increasingly important for HCWs to be fully vaccinated (CDC, 2013c) against communicable diseases such as influenza, hepatitis B, pertussis, measles, hepatitis A, and chickenpox. Mandatory vaccination policies for HCWs are recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (2013), as well as the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices and CDC. In addition, other organizations, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Hospital Association, and American Public Health Association, have released policy statements recommending that healthcare facilities institute, at a minimum, mandatory influenza vaccination of HCWs (Immunization Action Coalition, 2014).

Acknowledging the importance of HCW vaccination, many hospitals have implemented mandatory vaccination policies even without legal requirement to do so (Babcock, Gemeinhart, Jones, Dunagan, & Woeltje, 2010). Likewise, several hospital systems in Utah have enacted vaccination mandates for employees. In addition, Intermountain Healthcare, the largest healthcare provider in the region, implemented the Intermountain Healthcare compulsory immunization program in 2011 to protect patients and employees from vaccine-preventable diseases. Intermountain Healthcare requires vaccination of all employees, volunteers, students, vendors, and even temporary employees (Intermountain Healthcare, 2014). In addition, University Healthcare (University of Utah, 2011) and MountainStar Healthcare (M. Newns, personal communication, June 4, 2014) hospital facilities in Utah have instituted mandatory vaccination policies for HCWs.

Although the majority of Utah inpatient facilities have vaccination policies for employees, little is known about Utah outpatient clinics’ policies. Despite the less acute nature of patients in the outpatient clinic, a low employee vaccination rate still poses unwarranted risk to patients, particularly those who are children, older adults, or immunocompromised. Oncology clinics, in particular, are areas in which vaccination of HCWs is vital to the health of the immunocompromised patients, particularly because some vaccinations are contraindicated in patients with cancer who are undergoing radiation or chemotherapy treatments (Foster, Short, & Angelo, 2013; Lindsey, 2008). Even among immunocompromised patients in whom vaccinations are not contraindicated, vaccines may not be effective (Foster et al., 2013). Consequently, vaccination of those who have contact with patients with cancer is of paramount importance. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the vaccination policies of Utah oncology HCWs employed in outpatient oncology clinics. The objectives were to determine if Utah oncology outpatient clinics have employee vaccination policies and ascertain what consequences are included in the policy for employees who refuse vaccination.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study prior to data collection. The convenience sample included the managers of all 33 outpatient oncology clinics in Utah. Managers of inpatient treatment facilities were excluded from participation. A list of Utah oncology clinics was generated by comparing data from a general Internet search, contact with a local cancer center, and a search of oncologists credentialed with two large insurance companies. To be eligible for participation, the participant needed to be employed full- or part-time as the manager of at least one Utah outpatient oncology clinic.

Setting

The study took place in Utah, where vaccination rates are consistently below the national average (Utah Department of Health, 2014). As a result, Utah also has cases of vaccine-preventable diseases. According to the Utah Department of Health (2013), 237 cases of chickenpox, 12 cases of hepatitis A, and 29 cases of hepatitis B were reported in Utah during 2013. In addition, in 2013, Utah reported 1,077 cases of influenza that resulted in hospitalization (Utah Department of Health, 2013). The incidence of pertussis disease in Utah has steadily increased since 2009, surpassing the national average in 2013 with 1,307 cases (Utah Department of Health, 2013).

In Utah, the incidence rate for all cancers is 492.1 per 100,000 for males and 361.1 per 100,000 for females (American Cancer Society, 2015). Among all types of cancer reported in Utah, the most common include breast, cervical, colorectal, prostate, lung, and melanoma (Utah Cancer Action Network, 2016).

Design

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive study design. All outpatient oncology clinic managers in Utah were contacted via telephone to explain the aims of the study, as well as eligibility requirements for participation. Following the initial telephone contact explaining the study, the outpatient oncology clinic managers received a packet through the mail. Each packet contained an informed consent document, a study questionnaire, an addressed and stamped return envelope, and $1 as compensation for participation. Even without participation, the managers retained the $1 incentive. Four weeks after the initial mailing, nonresponders were sent a reminder packet that included another copy of the informed consent document, questionnaire, and addressed and stamped return envelope. No incentive was included in the second mailing. Eight weeks following the second mailing, the informed consent, questionnaire, and addressed and stamped return envelope were delivered by hand to the nonresponders and left with the receptionist, along with a $25 gift card. The manager retained the $25 gift card, regardless of participation in the study.

Instrument

The original instrument was developed by a group of Utah researchers and a panel of public health experts for use among managers employed in Utah outpatient pediatric clinics. The panel of public health experts included representatives from local and state health departments, healthcare providers from government subsidized clinics, and vaccination experts. The original questionnaire, used in the pediatric outpatient clinics, was pretested with 12 clinic managers in urgent care and family practice clinics and then adjusted according to the feedback of the clinic managers. The original questionnaire was then adapted by the same group of Utah researchers and public health experts to pilot in the outpatient oncology setting. The original instrument included two added questions for use in this study with oncology outpatient clinics. The adjusted two-page questionnaire included six demographic, eight multiple-choice, and four open-ended items (18 total).

Demographic items included questions on the clinic manager’s age, gender, and years worked as the clinic manager in that specific clinic. Participants were also asked to respond to questions about the clinic they managed, including location of the clinic (e.g., urban, suburban, rural), average number of patients served per day, and percentage of clinic employees working directly with immunocompromised patients during a routine workday.

The multiple-choice questions related to the clinic’s employee vaccination policy included which positions required vaccinations (e.g., front-office staff, back-office staff, in-house billing staff, support staff, clinic administrators). If employees were allowed to refuse vaccinations despite the presence of a clinic policy, clinic managers were asked to select the response that most closely resembled the circumstances under which refusals were allowed. Finally, clinic managers were asked if and when employee vaccinations were offered and whether the cost of employee vaccinations was paid by the employer. All multiple-choice questions offered an “other” category, where the clinic manager could write in his or her own response. Some questions required selecting only one answer, and others allowed the clinic manager to select all that applied.

Four questions were open-ended. The first question asked how long the clinic vaccination policy, if any, had been in effect. In addition, the clinic manager was asked how often the employee vaccination records were reviewed. A question about description of the most significant barrier to having an employee vaccination policy was also included. At the end of the questionnaire, a space was provided where clinic managers could write in any additional comments. The open-ended questions regarding the most significant barrier to having an employee vaccination policy and the additional comments are not included in this report because of a lack of saturation in responses.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into an SPSS®, version 21.0, database. Two independent researchers ensured the accuracy of data entry—one researcher read the questionnaire responses and the other researcher reviewed the entered data. The primary investigator examined unclear responses to determine the correct response. Frequencies, measures of central tendency, and dispersion were calculated for all quantitative items. Responses to open-ended items were analyzed by two independent researchers, each of whom conducted a content analysis.

Findings

Of the 33 questionnaires, 24 were returned for a response rate of 73%. Demographic data were collected about the clinic and clinic manager. The mean number of patients seen per day was 104.4 (SD = 159.95). The mean age of the clinic managers was 45.6 years (SD = 11.987). They were employed by the clinic for a mean of 13.3 years (SD = 7.892). The sample included 22 females and one male; one participant did not respond. Eleven of the clinics were in an urban location, five were rural, four were suburban, and four managers gave no response.

Vaccination Policy

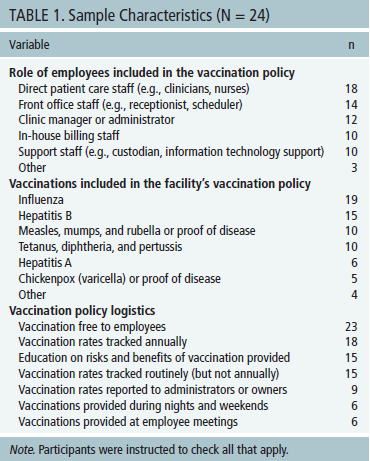

Data regarding the specific employees to which the vaccination policy applied were collected (see Table 1). Managers were asked to describe the vaccination policy, reporting which specific vaccinations were mandated. Data regarding the logistics of the vaccination policy also were obtained.

Consequences for Unvaccinated Employees

When asked to describe the clinic’s vaccination policy, nine managers reported that no consequence was in place for noncompliance and four reported that a consequence was in place for noncompliance, although the consequence was something other than termination or resignation. Seven managers reported that noncompliance with the vaccination policy resulted in the termination or resignation of the employee. Two managers reported that the clinic had no vaccination policy.

Of those who responded, six clinic managers reported having no additional work requirements for ill employees who refused the clinic policy vaccinations. Eleven managers required ill employees who were also unvaccinated to wear a mask at work. When asked to specify the symptoms for which additional requirements applied, nine managers required the unvaccinated employee to wear a mask when cough was present, seven managers required the unvaccinated employee to wear a mask when fever was present, and four required the unvaccinated employee to wear a mask when rash was present.

Although a little less than 50% of managers reported that employees must wear masks when ill, some unvaccinated employees were restricted from patient care duties if ill with a cough, fever, or rash. Six managers restricted employees from contact with patients when fever was present, four when they were ill with a rash, and three when they had a cough. One manager said employees were temporarily suspended or put on unpaid leave with the presence of a cough, fever, or rash.

Vaccine Refusal Process

Managers were also asked to report what type of vaccine refusals HCWs were allowed by the clinic policy. Of the responding clinic managers, 17 allowed HCWs to refuse vaccination for medical reasons when accompanied by a written excuse from the employee’s healthcare provider. HCWs were allowed to refuse vaccines for religious reasons, as reported by 14 managers. Other refusals included personal beliefs (n = 10) and medical reasons as reported by the employee (n = 9). One manager reported that refusals were not allowed.

Managers were asked to specify which information was included on the HCW vaccine refusal form. Twelve managers indicated that information regarding personal risk of vaccine refusal was included on the refusal form. In addition, 12 managers indicated that an employee signature was required along with an explanation for refusing the vaccine. Other information included risk to patients of vaccine refusal (n = 11) and facility rationale for requiring the vaccine (n = 9).

When reporting on documentation of employee vaccination refusal, 14 clinic managers reported that they kept a record of the refusal in paper form. The next most frequently selected response was that the employee’s refusal of vaccinations was not formally documented (n = 3).

Discussion

Despite the efficacy of vaccines in preventing the spread of infectious diseases, vaccination rates among HCWs remain suboptimal, even with strong recommendations from the CDC and multiple other professional healthcare associations (Rakita, Hagar, Crome, & Lammert, 2010). Optimal influenza vaccination rates among HCWs have proven to be particularly challenging (Caban-Martinez et al., 2010). As a result, protection for the spread of disease in some clinical environments was less than optimal. Even with the knowledge of suboptimal protection, and acknowledging the benefit of vaccines, many HCWs still go unvaccinated (Sullivan, 2010).

In the current study, most (n = 18) oncology clinic managers reported that the vaccination policy applied to HCWs employed in the direct patient care area, primarily referring to those with direct patient contact. Although HCWs with direct patient contact likely have the most physical contact with patients and, arguably, the most opportunity to spread infectious diseases to immunocompromised patients, they are not the only employees in whom vaccination can prevent the spread of disease. The CDC (2014a) defines HCWs as any person working in a healthcare setting that could have exposure to patients or any infectious agents. Although the CDC (2014a) definition of HCW includes nurses, doctors, and medical assistants, it also includes others, such as therapists, technicians, laboratory personnel, billing staff, custodians, clerical staff, laundry staff, administrators, students, and volunteers. Therefore, it is important for all HCWs to be fully vaccinated, regardless of the number and duration of direct patient encounters.

According to findings in the current study, vaccinations most frequently included in the oncology clinic vaccination policies were influenza and hepatitis B. Although these vaccinations are imperative, the CDC (2014d) also strongly recommends that HCWs receive additional vaccinations, such as measles, mumps, and rubella; chickenpox; pertussis; and meningococcal. Cases of measles, chickenpox, whooping cough, and meningitis occur every year in the United States and pose a direct threat to patients who are immunocompromised (Rubin et al., 2013). During 2014, measles cases peaked at their highest level for the prior 20 years (CDC, 2014c). Information on cases of chickenpox in the United States is limited (CDC, 2013a), and, although whooping cough cases are underreported in the United States, 28,660 cases were definitively diagnosed during 2014 (CDC, 2015). Meningococcal disease affects 800–1,500 individuals each year in the United States (CDC, 2014b). Because these diseases are still present in the United States and have potential to cause severe illness in immunocompromised patients, HCWs employed in oncology clinic settings should be fully vaccinated, reducing their risk of contracting illness themselves and then transmitting illness to patients.

Evidence shows that vaccination rates significantly improve with the presence of a workplace policy (Sullivan, 2010). However, discussion continues as to which elements included in policies will definitively result in improved HCW vaccination rates. Many call for mandating vaccination of HCWs because of the direct benefit to HCWs and patients but are contrasted by arguments for HCW personal liberty and personal belief. For example, Sullivan (2010) reported that voluntary HCW influenza vaccination programs were just as effective as mandated programs, some of which attained vaccination rates as high as 90%. In contrast, Podczervinski et al. (2015) found that HCW influenza vaccination rates were highest when policies included voluntary HCW vaccination with a penalty for noncompliance, namely completion of an education module. However, some facilities, such as Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), opted to institute a mandatory influenza vaccination policy for HCWs with a noncompliance penalty of termination. In the first year of CHOP’s implementation of this new policy, HCW vaccination rates for influenza surpassed 99% (Johnson & Talbot, 2011).

Some facilities require HCWs who refuse influenza vaccination to wear a mask during influenza season. However, such a penalty for noncompliance may be ineffective. According to Aiello et al. (2010), no statistical significance exists in reduction of respiratory illness transmission, even in HCWs wearing a mask during the entire influenza season. In addition, wearing a mask was found to be ineffective in protecting patients or HCWs from transmitting influenza (Ng, Lee, Hui, Lai & Ip, 2009). Rationale for failure of masks to prevent transmission of influenza includes issues with HCW noncompliance and episodes of unanticipated patient contact during the workday. Therefore, HCW vaccination against communicable diseases, such as influenza, remains superior in controlling transmission of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Limitations

This pilot study was limited in that participants were selected by convenience sampling. All participating clinics were located in Utah. Despite the inclusion of all Utah oncology clinics in the pilot study and a response rate of 73%, the sample size was small. As a result, the sample may not accurately represent outpatient oncology clinic facilities nationwide and may not be generalizable.

Implications for Practice

Patients with cancer have the right to receive care from a HCW who has taken the proper precautions to ensure patient safety and minimize patient harm (Ottenberg et al., 2011). Therefore, patients with cancer may already assume that their HCW has received all of the recommended vaccinations when this may not be the case. As patient advocates, oncology nurses should share credible patient education resources (see Figure 1) and empower clinic managers to question HCWs’ vaccination status.

Oncology nurses, in particular, have a special charge to lead practice change and influence and shape policy relating to the healthcare environment (Oncology Nursing Society, 2015). As powerful advocates for patient safety, oncology nurses can be instrumental in shaping vaccination policies in their respective institutions or clinics, positively influencing the health and safety of patients with cancer. Oncology nurses may want to begin by outlining the HCW vaccine recommendations by the CDC on the type of vaccines HCWs need in the healthcare environment and then encouraging key clinic policymakers, such as clinic administrators or human resources, to enact and enforce strict HCW vaccination policies. Oncology nurses should also oppose HCW refusal of vaccines for personal reasons and educate clinic policymakers on the lack of evidence supporting the use of masks as a penalty for unvaccinated HCWs who refuse vaccinations. In addition, oncology nurses can easily adapt established vaccination policies in local hospitals for use in the outpatient oncology setting.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"26136","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"211","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"371"}}]]

Conclusion

Low vaccination rates among HCWs in outpatient settings could be problematic, putting patients and HCWs at risk for preventable illnesses. Low HCW vaccination rates in the oncology setting are particularly problematic because these HCWs care for immunocompromised patients. To protect the health of patients undergoing oncology treatments, HCWs have a professional obligation to be fully vaccinated and to lead policy change that positively influences the health and safety of patients, particularly those who are immunocompromised.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"26141","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"189","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"766"}}]]

References

Aiello, A.E., Murray, G.F., Perez, V., Coulborn, R.M., Davis, B.M., Uddin, M., . . . Monto, A.S. (2010). Mask use, hand hygiene, and seasonal influenza-like illness among young adults: A randomized intervention trial. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 201, 491–498. doi:10.1086/650396

American Cancer Society. (2015). Cancer facts and figures 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/…

Babcock, H.M., Gemeinhart, N., Jones, M., Dunagan, W.C., & Woeltje, K.F. (2010). Mandatory influenza vaccination of health care workers: Translating policy into practice. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50, 459–464. doi:10.1086/650752

Caban-Martinez, A.J., Lee, D.J., Davila, E.P., LeBlanc, W.G., Arheart, K.L., McCollister, K.E., . . . Fleming, L.E. (2010). Sustained low influenza vaccination rates in US healthcare workers. Preventive Medicine, 50, 210–212.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60, 619–623.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012a). Adults need vaccines, too. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/features/adultimmunizations

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012b). There are vaccines you need as an adult. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013a). Chickenpox (varicella): Outbreaks. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/outbreaks.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). Influenza vaccination information for health care workers. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/healthcareworkers.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013c). State immunization laws for healthcare workers and patients. Retrieved from http://www2a.cdc.gov/vaccines/statevaccsApp

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014a). Influenza vaccination information for health care workers. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/healthcareworkers.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014b). Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases: Chapter 8: Meningococcal disease. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt08-mening.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014c). Measles cases in the United States reach 20-year high. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0529-measles.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014d). Recommended vaccines for healthcare workers. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/hcw.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Notifiable diseases and mortality tables. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, ND-1-ND-19.

Foster, S.L., Short, C.T., & Angelo, L.B. (2013). Vaccination of patients with altered immunocompetence. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 53, 438–440. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2013.13526

Immunization Action Coalition. (2014). Influenza vaccination honor roll. Retrieved from http://www.immunize.org/honor-roll/influenza-mandates

Infectious Diseases Society of America. (2013). IDSA, SHEA, and PIDS joint policy statement on mandatory immunization of health care personnel according to the ACIP-recommended vaccine schedule. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2bBtPWm

Intermountain Healthcare. (2014). Immunization policy. Retrieved from http://intermountainhealthcare.org/health-resources/immunization-policy…

Johnson, J.G., & Talbot, T.R. (2011). New approaches for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 24, 363–369.

Lindsey, H. (2008). Preventing infection in immunocompromised cancer patients: Latest recommendations. Oncology Times, 30, 25–26, 28. doi:10.1097/01.COT.0000340713.41105.fa

Ng, T.C., Lee, N., Hui, S.C., Lai, R., & Ip, M. (2009). Preventing healthcare workers from acquiring influenza. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 30, 292–295. doi:10.1086/595690

Oncology Nursing Society. (2015). Lifelong learning for professional oncology nurses. Retrieved from https://www.ons.org/advocacy-policy/positions/education/lifelong

Ottenberg, A.L., Wu, J.T., Poland, G.A., Jacobson, R.M., Koenig, B.A., & Tilburt, J.C. (2011). Vaccinating health care workers against influenza: The ethical and legal rationale for a mandate. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 212–216. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.190751

Podczervinski, S., Stednick, Z., Helbert, L., Davies, J., Jagels, B., Gooley, T., . . . Pergam, S.A. (2015). Employee influenza vaccination in a large cancer center with high baseline compliance rates: Comparison of carrot versus stick approaches. American Journal of Infection Control, 43, 228–233.

Rakita, R.M., Hagar, B.A., Crome, P., & Lammert, J.K. (2010). Mandatory influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: A 5-year study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 31, 881–888. doi:10.1086/656210

Rubin, L.G., Levin, M.J., Ljungman, P., Davies, E.G., Avery, R., Tomblyn, M., . . . Kang, I. (2013). 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58, e44–e100. doi:10.1093/cid/cit684

Sullivan, P.L. (2010). Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: Should it be mandatory? Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2c8oPWc

University of Utah. (2011). Immunization information. Retrieved from https://www.hr.utah.edu/serviceTeams/immunization.php

Utah Cancer Action Network. (2016). 2016–2020 Utah comprehensive cancer prevention and control plan. Retrieved from http://www.ucan.cc/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/State-Cancer-Plan-Revisio…

Utah Department of Health. (2013). Communicable disease annual report, Utah, 2013. Retrieved from http://health.utah.gov/epi/data/annualreport/2013_CD_Annual_Rpt.pdf

Utah Department of Health. (2014). Immunization coverage levels. Retrieved from http://www.immunize-utah.org/statistics/utah%20statistics/immunization%…

Williams, W.W., Lu, P., O’Halloran, A., Bridges, C.B., Pilishvili, T., Hales, C.M., & Markowitz, L.E. (2014). Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63, 95–102.

About the Author(s)

Karlen E. Luthy, DNP, FNP-c, is an associate professor, Sarah L. Stocksdale, BS, FNP-s, is a graduate student, Janelle L.B. Macintosh, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor, Lacey M. Eden, MS, FNP-c, is an assistant teaching professor, and Renea L. Beckstrand, PhD, RN, CCRN, CNE, is a professor, all in the College of Nursing at Brigham Young University in Provo, UT; and Katie Edmonds, BS, RN, is an RN at the Thyroid Institute of Utah in Provo. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The authors did not receive honoraria for this work. The content of this article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is balanced, objective, and free from commercial bias. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the authors, planners, independent peer reviewers, or editorial staff. Luthy can be reached at beth_luthy@byu.edu, with copy to editor at CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2015. Revision submitted November 2015. Accepted for publication December 11, 2015.)