Oncology Nurse Navigation: Results of the 2016 Role Delineation Study

Background: In 2011, an oncology nurse navigator (ONN) role delineation survey (RDS) was conducted by the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) when the role was relatively new to oncology. Results did not demonstrate a unique skill set for the ONN; however, since then, the role has expanded.

Objectives: ONS and the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation partnered in 2016 to complete an RDS of ONNs to redefine the role and determine the need for an ONN certification examination.

Methods: A structured RDS was conducted using a formal consensus-building process. A survey was developed and released to examine the specific tasks, knowledge, and skills for the ONN as well as to determine which role possesses more responsibility for the tasks: the ONN or the clinical or staff nurse.

Findings: The ONN role is evolving, and more was learned about its key tasks, including differences in the responsibilities of the ONN and the clinical or staff nurse. However, the RDS did not find an adequate difference in the knowledge required by the ONN and the clinical or staff nurse to support the need for a separate ONN certification.

Jump to a section

Care coordination is an essential component of high-quality patient care regardless of the patient’s health state, disease status, or location of care. Although it has been considered an integral component of nursing care for some time, care coordination, including its process and components, has recently received more focus in response to calls to improve patients’ care experience, enhance the health of all populations, and reduce healthcare costs (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2012; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2011). The ANA (2012) has led multiple initiatives to underscore nurses’ critical role in care coordination. Other organizations, such as the American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (2016) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016), have also been involved in care coordination projects.

Care coordination is an integral component of oncology nursing. According to the Oncology Nursing Society’s (ONS’s) Statement on the Scope and Standards of Oncology Nursing Practice: Generalist and Advanced Practice, “The oncology nurse functions as a patient care coordinator and collaborates with other health care team members to provide high-quality interdisciplinary care” (Brandt & Wickham, 2013, p. 10). However, multiple barriers to timely care have been identified, such as difficulty navigating the healthcare system, poor communication, misunderstanding, fear, anxiety, and lack of resources (Blaseg, 2014). The oncology nurse navigator (ONN) role has the potential to address and perhaps overcome some of these challenges (Cantril, 2014).

The ONN role has continued to develop with diverse implementation of patient navigation in cancer care. Further expansion of patient navigation in cancer care and specifically the ONN role has most recently been driven by the Commission on Cancer (CoC) Standard 3.1: Patient Navigation Process (American College of Surgeons [ACoS], 2012). Although CoC Standard 3.1 does not indicate that a navigator is needed, many programs have added or expanded ONN roles to ensure that they are meeting the standard. The CoC Cancer Program Standards were updated in 2016 and clarified that hiring a navigator is not required as the focus of the standard is the process of care coordination (ACoS, 2016). In addition, the ONN role has further expanded to support organizational strategies across the cancer care continuum. Although patient navigation began with screening and diagnosis, it now extends from screening through survivorship and end-of-life care. ONNs may support a specific phase or all phases across the continuum—depending on the organizational design.

Full implementation of the ONN role has been difficult in all oncology settings because of the challenges presented by its rapid expansion and shifting priorities in patient navigation. In many organizations, the ONN role is designed to bridge gaps in continuity of care and support various care processes. In addition to supporting CoC Standard 3.1, ONNs often have the responsibility for the CoC Continuum of Care cancer standards for psychosocial distress screening and survivorship care plans. Many ONNs also are expected to demonstrate the value of their role and the navigation program. The current direction of cancer care and patient navigation requires periodic role evaluation to provide role clarification, support the expanded role, and define the added value that ONNs bring to the patient experience as well as to outcomes and cost of care.

In 2011, ONS conducted a role delineation study (RDS) to explore the job-specific functions of the ONN (Brown et al., 2012). At that time, the ONN role was relatively new and its functions and responsibilities were not well understood. Although the 2011 RDS identified a set of tasks specific to the ONN role, the data did not demonstrate how the identified knowledge, tasks, and skills could be differentiated from those performed by nurses who held other Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation (ONCC) certifications, especially the OCN® credential (Brown et al., 2012). In recognition of the expanding use of ONNs and the inability of the 2011 RDS to demonstrate a unique skill set for the ONN, ONS and ONCC partnered to conduct a new RDS in 2016. The goal of the 2016 RDS was to define the current role of the ONN and determine whether data from this new survey would support the development of an ONN certification examination.

Methods

An RDS is conducted to determine the tasks, knowledge, and skills necessary to perform a job safely and effectively (Duke & Meyer, n.d.). A well-executed RDS follows prescribed steps to provide legal defensibility and assurances that tasks, knowledge, and skill requirements are derived from a rigorous process and not built on bias or vested interests (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014). Throughout the phases of the RDS, the key to building consensus is working with subject matter experts, who in this case identified themselves as practicing ONNs. Those who perform the role being studied are asked to describe in detail what they do and what is required for them to be able to fulfill the role. The RDS “helps to ensure that workers know exactly what is needed to perform their jobs safely and efficiently” (Duke & Meyer, n.d., p. 9). Furthermore, it allows “practitioners to study aspects of practice—whether it is in the context of introducing an innovative idea or in assessing and reflecting on the effectiveness of existing practice, with the view of improving practice” (Koshe, 2005, p. 9).

ONS and ONCC contracted with an outside company, Prometric, to facilitate the 2016 ONN RDS process. Prometric has extensive experience with test development and was brought in to manage the RDS and collect data that could be used to determine whether a specific ONN certification was warranted based on new information from ONNs about the tasks, knowledge, and skills necessary to perform the role.

To begin the process, a call for volunteers was disseminated to all ONS members through an emailed ONS Connect Weekly News Update and targeted email messaging to more than 3,300 members of the ONS Nurse Navigation Special Interest Group and members who self-identified as nurse navigators. A total of 118 volunteer applications were received from ONS members who were interested in participating as task force members and/or pilot testers. Ten subject matter experts from the interested applicants were chosen for the ONN RDS task force based on their answers to questions about their experience with role delineation or competency development, their strengths, and their rationale for participation. In addition, to ensure diversity, the selection committee considered the applicants’ years of experience as an RN and as an ONN, work setting, education level, current credentials, and geographic location.

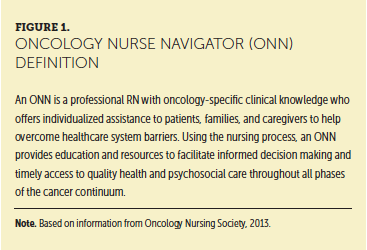

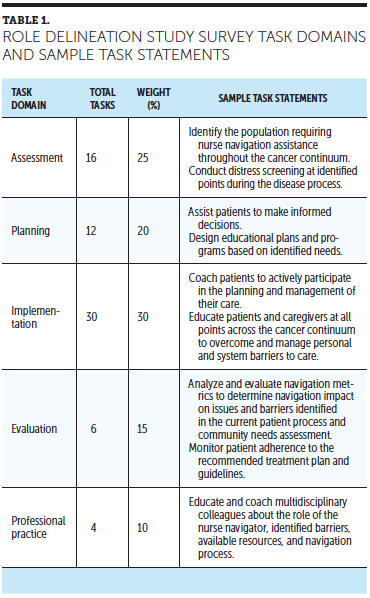

Using the 2011 RDS as a starting point, the ONN RDS task force was first asked to define oncology nurse navigator. The task force decided to adopt the definition from the ONS (2013) ONN core competencies (see Figure 1). Building on that definition, data from the 2011 RDS, and the expertise of the task force members, the task force deliberated and reached consensus on statements concerning tasks (n = 68), knowledge (n = 36), and skills (n = 25) that they felt were essential for competent practice as an ONN in the current healthcare environment. Many of the task statements used in the 2011 RDS were reworded to better reflect the current role of the ONN or make them easier to interpret. For example, the 2011 tasks that focused on identification of patients suspected of having cancer, with a new diagnosis of cancer, or with a recurrence were replaced with one task statement related to identification of populations requiring nurse navigation assistance throughout the cancer continuum. The tasks were then divided into five domains of practice consistent with the 2011 RDS: assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation, and professional practice. The knowledge and skills reflected broader concepts that crossed the domains. These agreed-upon tasks, knowledge, and skills formed the basis of a draft survey.

To ensure that the survey instructions and questions were clear, a pilot test of the draft survey was completed. Twenty-four subject matter experts who had previously indicated interest in participating in the pilot test were asked to validate, negate, add, or comment on the identified role requirements in the draft survey. Eighteen subject matter experts completed the pilot test and provided feedback about the need to reword some of the questions to clarify what specifically was being requested. Two additional tasks were added to the evaluation domain related to analyzing use of and identifying gaps in available resources. No other changes were made to the task, knowledge, and skill statements.

Using specific feedback from the pilot survey group, the task force edited the survey to create the final version. Although seemingly redundant, this step added validity to the final survey. Refining the survey based on pilot-test feedback also ensures that tasks are not forgotten (Duke & Mayer, n.d.). Once finalized, the survey was distributed to 5,397 ONS members and nonmembers identified in the ONS database as ONNs or members of the ONS Nurse Navigator Special Interest Group. An email invitation was sent with a link to the Prometric survey with a request to complete the survey within five weeks. Two email reminders were sent from both Prometric and ONS/ONCC, and the survey deadline was extended by four days to encourage completion of the survey, especially for those who had started but not completed it.

Survey Construction

The survey developed for the RDS had five sections:

• Background and general information: This included descriptive questions about the respondents, such as demographic characteristics and professional activities.

• Tasks: The tasks identified by the task force as potentially important to the ONN role were listed by domain in this section (see Table 1). Respondents were asked to answer two questions about each task regarding its importance and where the primary responsibility for the task was in their current role.

“How important is this task in your current role?” This question was rated using a five-point Likert-type scale from 0 (no importance) to 4 (very important).

“Is the oncology nurse navigator more responsible for this task than a clinical/staff nurse in your facility?” This question was answered with yes or no.

• Knowledge and skills: Using the same five-point Likert-type scale as in the tasks section, respondents were asked to rate the importance of each identified knowledge and skill requirement for their current role.

• Weighted recommendation: Respondents were asked what weight (in percentages that added to 100) each knowledge domain should receive if a certification test was developed.

• Comments: The final section included open-ended questions to evaluate current and future professional development needs.

After the survey closed, the responses were analyzed by a small group of subject matter experts, including five members from the task force and five new subject matter experts. The new subject matter experts were identified from the original set of volunteers for this project with the intent of ensuring continued diversity in years of experience as an RN and as an ONN, work setting, education level, and geographic location. The group was tasked with three duties: (a) to determine which tasks, knowledge, and skills were important for the ONN role; (b) to create links among the tasks, knowledge, and skills; and (c) to group the task, knowledge, and skill requirements into specific content areas. The subject matter experts then reached consensus on the relative weight of importance that should be assigned to each task domain.

Results

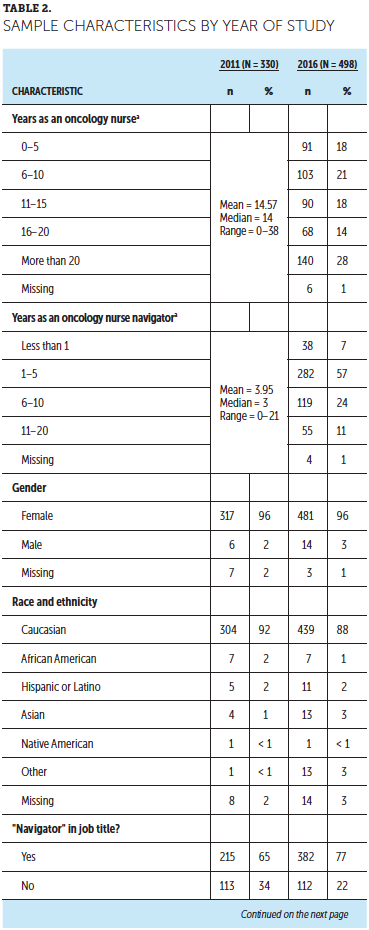

Invitations to complete the survey were sent to 5,397 individuals in the ONS database who self-identified as nurse navigators or members of the ONS Nurse Navigation Special Interest Group. A total of 498 surveys were completed and contained sufficient information to be included in the analysis (9% return rate). An evaluation of the demographic data demonstrated that the respondents represented the sample sufficiently to allow for statistical analysis (Prometric, personal communication, February 2016). Respondents were all RNs from the United States, with representation from 47 states. Respondents most commonly worked in suburban settings (60%), and 75% worked in ambulatory settings, with 25% in inpatient settings. Most worked in site-specific navigation roles, and breast and lung cancers were reported most commonly (see Table 2).

Most respondents reported that their primary job title included the term navigator, and 17% stated that they were case managers or coordinators. Other reported job titles included program nurse, care manager, and clinical coordinator. Most respondents were members of ONS (59%), whereas other respondents were members of the Academy of Oncology Nurse and Patient Navigators and state navigation coalitions or organizations.

The 68 task statements included on the survey were evaluated based on mean importance ratings and frequency with which respondents reported that the ONN was more responsible for performing the task than the clinical or staff nurse in their setting. Four of the task statements were removed as they did not reach the predetermined importance rating of 2.5 (out of 4) and were not found to be more of the ONN’s responsibility than the clinical or staff nurse’s. Two additional task statements were removed as respondents reported they were not sufficiently important to retain or were not commonly an ONN’s responsibility, respectively: (a) “Identify people at high risk for cancer requiring screening” and (b) “Organize/facilitate cancer-related support groups for patients and caregivers.” The remaining 62 task statements were spread across the domains. All 36 knowledge requirements were rated as important or highly important to the ONN role and all were retained. Of the 25 skill statements, two were eliminated as they were rated with little to moderate importance to the ONN role (grant writing and marketing).

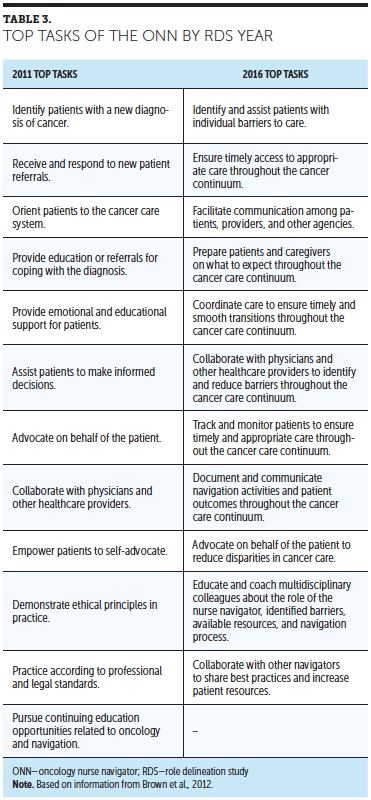

Of the 62 tasks identified, four key concepts emerged: access, barriers, care coordination, and communication. Several of the tasks focus on the ONN as the essential point of contact for patients and caregivers regarding facilitation and access to care throughout the cancer care continuum. In addition, ONNs, either by themselves or in collaboration with other members of the healthcare team and the community, are responsible for identifying and addressing barriers that can inhibit optimal care (i.e., patient-specific or organization- or healthcare system–related barriers). Coordination of care is also essential to ensure timely access and smooth transitions throughout the cancer care continuum. Communication across caregivers and systems, including patients and caregivers, other members of the healthcare team, and internal and external organizational resources, is critical for smooth transitions and best outcomes of care. Table 3 provides a list of the primary responsibilities identified for ONNs.

Of the 36 knowledge statements, the most highly ranked areas were pathophysiology of cancer, multimodality treatment planning, goals of care, symptom management, quality of life, and evidence-based practice guidelines. Of the 23 skill statements, communication, collaboration, critical thinking, problem solving, advocacy, multitasking, time management, and patient and family education were rated as important. These knowledge and skill statements were clearly consistent with the main concepts identified in the task portion of the ONN RDS survey.

In the final section of the survey, respondents provided more than 500 responses to questions focused on current and anticipated professional development needs. During analysis of the responses, several themes emerged: the patient’s needs related to survivorship issues, management of psychosocial issues, new treatments, technologies and systems, disease-specific updates, financial aspects of care, metrics and outcome data collection and analysis, and improving communication with patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

Discussion

The results of the 2016 ONN RDS supported the belief expressed to ONS leadership that the ONN role has been expanding and evolving rapidly since 2011. New areas of importance for the ONN role emerged in the 2016 RDS. Some of these new tasks focus on psychosocial aspects of care, such as distress screening, survivorship care planning and communication, facilitating and providing support during difficult conversations, and facilitating advanced care planning. Others focused on the process of care, such as identification of patients appropriate for genetic counseling, designing educational plans and programs, and monitoring for patient adherence. The results supported the importance of identifying gaps in services and resources and evaluating the impact of navigation on processes and patient outcomes through tracking, documenting, and reporting navigation metrics.

The 2016 RDS also provided data that indicated some differences between the role of the ONN and that of the clinical or staff nurse. Although many areas overlap between the ONN and the clinical or staff nurse roles, such as psychosocial support for patients and caregivers, ensuring proper patient care, collaboration with multidisciplinary teams and caregivers, and providing evidence-based education to patients and caregivers, numerous tasks are associated more strongly with the ONN. The difference between the roles appeared to be centered around the focus of daily practice. The clinical or staff nurse usually focuses on meeting patients’ clinical needs in one setting whereas the ONN most often provides care coordination, guidance, education, and advocacy across care settings. For instance, an ONN is concerned with practical matters such as patient transportation, financial resources, and ensuring that patients have correct referrals and information to make appropriate decisions. In terms of professional practice, the ONN focuses on educating and coaching multidisciplinary colleagues about their role, collaborating to learn best practices, and marketing navigation services. The professional performance focus of the clinical or staff nurse is on direct patient care, treatment, and management of side effects.

Both roles, however, require similar knowledge and skills. The knowledge requirements identified through the RDS were compared to the 2016 OCN® Test Content Outline and a strong congruence was found (ONCC, 2016). About 74% of the knowledge statements on the 2016 ONN RDS were an exact match or aligned with a very similar item found on the OCN® Test Content Outline. At this time, the results do not support the need for a separate and unique ONN certification and reinforce the ONS (2015) position statement on Oncology Nurse Navigation Role and Qualifications: “Nurses in ONN roles should possess certification through one of the National Commission for Certifying Agencies–accredited certifications offered by the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation—minimally, Oncology Certified Nurse (OCN®)”.

Implications for Practice and Future Navigation Work

The results of the RDS will likely be used in many ways to increase the understanding of the role of the ONN, particularly for the tasks rated with high importance and/or the primary responsibility of the ONN. In addition, a focus on the tasks newly identified in this survey as important to the role, such as providing support during difficult conversations, facilitating advanced care planning, monitoring patient adherence, and tracking, documenting, and reporting on navigation metrics, can help define areas for future growth of navigation programs.

ONS is in the process of updating the ONN Core Competencies, which will reflect the tasks, knowledge, and skills identified in the 2016 ONN RDS. The ONN RDS task force members identified many ways in which the data collected in this RDS and the coming changes to the ONN competencies might impact practice at both the institutional and individual levels. On the institutional level, the key concepts that underpin the role as well as the top tasks listed as primary responsibility of the ONN can help develop position descriptions and serve as a guide to determine pertinent job responsibilities. While setting clear expectations for what the ONN can contribute to the organization, position descriptions can help identify the resources that ONNs need to perform their jobs effectively. The key concepts and tasks might also help institutions justify the need for ONNs as an essential driver of patient satisfaction and organizational efficiencies.

The results of the RDS may be helpful in establishing and evaluating measurable outcomes of the navigation program, such as decreasing outmigration, increasing patient and physician satisfaction, and decreasing emergency room visits (Struskowski & Stapp, 2016). Metrics might be used to demonstrate system efficiencies gained through the efforts of the ONN. On an individual level, delineating the role will help ONNs prioritize responsibilities and delegate tasks that can be completed by support staff. In addition, defining the role will help ONNs determine their focus for continuing education and nursing certifications.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"29276","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"154","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"362"}}]]

Conclusion

Nursing navigation provides an opportunity to focus on patient care needs that cross settings, streamlining transitions and overcoming barriers to quality care. The release of the CoC Standard 3.1 in 2012 led many accredited programs to hire ONNs to fulfill navigation requirements. However, many programs did not have concrete resources describing the ONN role, so many programs were developed from scratch and evolved by trial and error. A clearer role description outlining key tasks and behaviors can provide new programs with a starting point from which to move forward.

The 2016 RDS provides data demonstrating that while many of the core components of the ONN role remain the same over time, the role is evolving and clearer themes of ONN focus are emerging. In addition, the 2016 RDS supports a differentiation from the direct care nurse role and identifies some unique contributions that the ONN makes to quality processes and patient outcomes. The ONN is instrumental in eliminating barriers across the healthcare continuum in areas such as prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care. This can lead to not only greater patient satisfaction and improved care, but also improvement in systems efficiencies and potentially cost savings.

ONS and ONCC are currently in the process of exploring strategies to further support the role of the oncology nurse and ONN in care coordination. However, the need for and sustainability of a separate and unique ONN certification is not supported at this time.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Brenda Nevidjon, MSN, RN, FAAN, for her thoughtful review and comments. The authors also thank all the subject matter experts who contributed to the development, piloting, and review of role delineation survey and results.

About the Author(s)

Barbara G. Lubejko, RN, MS, is an oncology clinical specialist at the Oncology Nursing Society in Pittsburgh, PA; Sonia Bellfield, RN, MS, OCN®, is a clinical research nurse coordinator at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD; Elisa Kahn, MSOL, DMA, MM, BS, is a certification specialist and consultant for the Institute of Credentialing Excellence in Washington, DC; Carrie Lee, RN, BSN, OCN®, is an immuno-oncology clinical liaison at Bristol-Myers Squibb in Zanesville, OH; Nicole Peterson, RN, BSN, OCN®, is an oncology nurse navigator at CHI Health in Elkhorn, NE; Traudi Rose, RN, BSN, MBA, OCN®, is a VISN20 program manager for the Cancer Care Navigation Team at the VA Portland Healthcare System in Oregon; Cynthia Miller Murphy, MSN, RN, CAE, FAAN, is the executive director at the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation in Pittsburgh; and Michele McCorkle, RN, MSN, is the executive director at the Oncology Nursing Society. Lubejko can be reached at blubejko@ons.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2016. Accepted November 22, 2016.). The authors take full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias.