Family Caregivers: A Qualitative Study to Better Understand the Quality-of-Life Concerns and Needs of This Population

Background: While providing physical, psychological, and spiritual care to their loved ones with cancer, family caregivers (FCGs) are physically and emotionally vulnerable to the tolls of caregiving. Patients and FCGs experience the uncertainty that comes with illness and treatment, its side effects, the lack of control, the emotional upheaval, the spiritual doubt, and the helplessness of advancing disease.

Objectives: This study was conducted to better understand the quality-of-life needs of the FCG population, particularly those who encounter financial strain related to patients’ cancer and treatment.

Methods: This qualitative study of FCG concerns was conducted in association with a randomized trial of an FCG support intervention. Twenty FCGs of patients with solid tumor cancers were interviewed in person or via telephone for this study. The FCG version of the City of Hope quality-of-life tool, which consists of four domains of well-being (physical, psychological, social, spiritual), was applied to the content analysis of interviews.

Findings: Care for FCGs is needed across all quality-of-life domains.

Jump to a section

One of the most significant factors in the oncology workforce, or among those who care for patients with cancer, is the availability and support of family caregivers (FCGs). These individuals are providing complex cancer care at a time when such care is shifting more into the home, away from the inpatient setting, and when the aging population is affecting patients and FCGs (Goren, Gilloteau, Lees, & DaCosta Dibonaventura, 2014; National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP Public Policy Institute, 2015; Nielsen, Neergaard, Jensen, Bro, & Guldin, 2016). Older adults with cancer often have multiple comorbidities and care needs in addition to their cancer, and older FCGs often face illnesses themselves (Girgis, Lambert, Johnson, Waller, & Currow, 2013; Hudson, Thomas, Trauer, Remedios, & Clarke, 2011). The importance of FCGs prompted the National Academy of Science in 2016 to produce a report on this topic (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). The report urges that more attention be paid to caregiving in illnesses such as cancer, as well as that related research be expanded and models of care be developed.

Caregiving and serious illness are also known to take an enormous financial toll on patients and families (Zafar, 2015). Direct costs of cancer care include medications, diagnostic tests, and co-payments for clinic visits and hospitalizations. FCG expenses are also substantial, including lost work time, travel costs, and patient assistance to meet financial demands (Zafar et al., 2013). This qualitative study explored cancer caregiving in a population of FCGs who were experiencing financial strain because of cancer and its treatment. The study findings offer direction for oncology clinicians to provide support to FCGs (Kamal et al., 2017).

Literature Review

A systematic review of family caregiving in cancer analyzed literature from 2009–2016. More than 800 articles were found; of these, 50 were randomized trials of FCG interventions. These trials were largely psychoeducational (64%), with 22% that were skills-based trials and 15% that were counseling trials. The interventions themselves were often couples-based (53%), and all the interventions were evenly divided between face-to-face interviews and telephone-based interviews (Ferrell & Wittenberg, 2017). The most predominant areas of intervention content focused on physical care or symptom management (72%) and FCG self-care (68%) (Ferrell & Wittenberg, 2017).

Beyond these randomized studies of interventions, numerous observational studies or review articles have described the impact of family caregiving (Candy, Jones, Drake, Leurent, & King, 2011; James, Hughes, & Rocco, 2016; Thomas, Dalton, Harden, Eastwood, & Parker, 2017). FCGs report physical strain and symptoms (e.g., sleep disruption, fatigue) associated with the physical burden of providing care. Studies have consistently noted that the psychological symptoms reported by FCGs, including anxiety and depression, are similar to those of the patients for whom they care. Social concerns of FCGs include issues of sexuality and intimacy, financial strain, and changes in roles or relationships (AARP, 2016; Kamal & Dionne-Odom, 2016; Kavalieratos et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2015).

Although there has been a substantial increase in literature related to patient spirituality, limited attention has been paid to FCGs’ spiritual needs (Sun et al., 2016). In addition, some articles have mentioned the positive aspects of family caregiving; many FCGs derive great meaning and benefit from caring for their ill family member (Li & Loke, 2013).

Methods

This qualitative study of FCG concerns was conducted in association with a randomized trial of an FCG support intervention. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the investigators’ institution, City of Hope Medical Center in Duarte, California, and written consent was obtained from FCGs. The randomized trial of the FCG intervention is in progress and will include 225 FCGs of patients with solid tumor cancers. After the first year of study accrual, the investigators recognized a need to gather qualitative data to better understand the needs of this population of FCGs across all quality-of-life domains (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being) (Kent et al., 2016; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013). The study specifically targeted FCGs experiencing financial strain related to patients’ cancer and treatment; this was determined in the screening process by asking FCGs if they or the patients for whom they were caring were experiencing financial distress as a result of the disease or treatment.

The researchers employed a convenience sample of 20 FCGs enrolled in the randomized trial of the FCG intervention to participate in a one-time interview conducted in person or via telephone. An interview guide based on the FCG version of the City of Hope quality-of-life tool (Sun et al., 2016) was used and consisted of questions asking the FCGs to describe their own physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being, as well as the financial strain they had experienced during caregiving. An additional question asked FCGs to describe what they did to care for themselves. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, and they ranged from 20–40 minutes in length. Transcripts were analyzed by the investigators using thematic content analysis. Themes and subthemes were identified, and tables that had been constructed to summarize the quotes by theme were reviewed by members of the research team with extensive experience in qualitative research.

Results

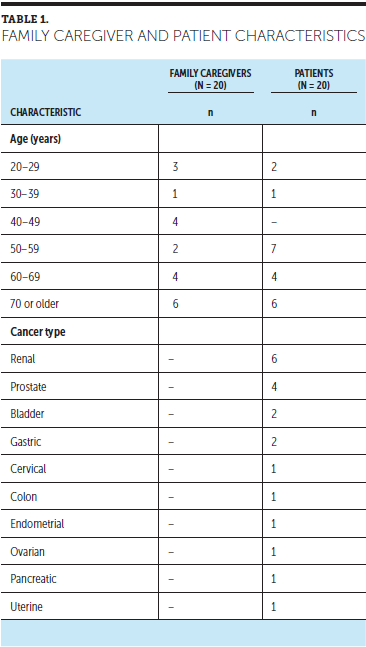

Table 1 summarizes FCG and patient demographic data. FCGs and patients ranged in age (28–80 years and 26–78 years, respectively). More than half of the FCGs were White (n = 11), with Hispanic being the most prominent minority population (n = 6). Two FCGs were identified as Black, and one FCG indicated other or unknown ethnicity. Fourteen FCGs were women, and six were men. The patients had a variety of multiple solid tumor diagnoses.

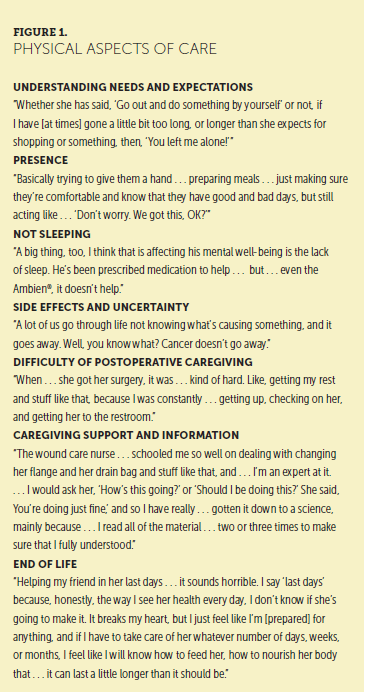

Physical Aspects of Care

As cancer care is shifting away from healthcare settings into the home, family members are often forced to take on the responsibility of caring for their loved ones without training and preparation (Given, Given, & Sherwood, 2012). The first category of themes that arose from interviewing FCGs concerned the physical aspects of care. Although some FCGs spoke of experiencing family cohesion and unity and not finding caregiving to be difficult, the majority of FCGs cited challenges in providing care to family members with cancer. FCGs reported that understanding and anticipating the needs and expectations of their loved ones was difficult. Needs of their family members with cancer often shifted, and FCGs said they wanted to understand patients’ needs, as well as be present, attentive, and reassuring, while also preparing meals, offering care, and ensuring that their loved ones were comfortable (see Figure 1). One FCG further described this struggle:

What has been the most challenging in caring for the patient’s physical needs? Trying to understand what they need at the moment, trying to help them . . . be there for them. . . . They say they don’t want this, they don’t want that, but you offer and don’t ever get tired.

The most repeated physical care theme was the presence and difficulty of dealing with treatment side effects. FCGs reported that patients experienced various side effects, including fatigue, nausea, constipation, neuropathy, headaches, mouth blisters, and the inability to sleep. One FCG stated, “There have been a variety of things over the years, and any one or two or three of these things may be affecting her on a given day.” Referring to treatment, one FCG noted that side effects recurred weekly: “It’s been very challenging for her, but we’ve come to the conclusion that Wednesdays throughout treatment are never going to be good.” About a loved one’s lack of sleep, one FCG noted, “She’s always fighting her sleep. She’ll not sleep. She doesn’t get nearly as much sleep as she should, her being on treatment. She needs it more.”

FCGs grappled with the uncertainty that accompanied the treatment side effects and the cancer itself. One patient fell and experienced pain after the fall. Doctors could not determine if the pain was because of the fall or attributable to a new ailment:

I drive him there at 2 o’clock in the morning. I come home. . . . It’s 5. . . . They take a picture of his head. They give him. . . meds, and he’s feeling a little better. But he never does get to feeling really terrific. . . . Mind you, we had stopped . . . the cancer drugs. So, the question is, is it the fall, or is he developing something else? We don’t think he’s having a stroke because he’s been taking his blood pressure and it’s good. . . . We don’t know why he doesn’t feel good.

Overall, cancer brings uncertainty to the lives of patients and FCGs that may never go away. In addition, FCGs said that the support from hospital staff support was extremely valuable. One FCG praised the wound care nurse who taught her how to change the flange and drain bag. The FCG described herself as an “expert” at care, having read all the instructions multiple times; she worked with the wound care nurse and was assured by the nurse that she was correctly performing the caregiving tasks.

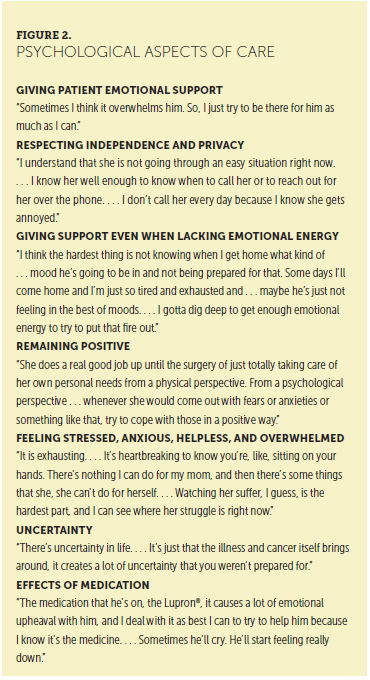

Psychological Aspects of Care

FCGs spoke about the psychological challenges faced by patients with cancer and the psychological effects of caregiving (see Figure 2). A frequent theme expressed by FCGs was being present to offer support even when they lacked the emotional energy to do so. One FCG spoke about being sensitive to the patient’s moods while trying not to “baby” him, but also noting that “you want to care for them . . . and so . . . you’re kind of caught there in the middle.” Another reported she was careful not to bother the patient too much while trying to be present and in touch daily or every other day, either by text message or telephone call. Other FCGs reported the need to maintain a positive environment. One FCG noted actively trying to offset the negative thoughts of her loved one with positive thoughts, whereas another FCG said he used motivational audio recordings to help increase positivity while caring for his wife:

I certainly felt the need and the responsibility to just be very positive, loving, and try to make the experience as comfortable as possible and took on some additional roles. . . . It was just important to keep as positive of an environment as possible.

According to one FCG, physical caregiving was needed less than “the emotional aspect” of caregiving. Another FCG said focus was not placed on the cancer but rather on the patient’s health needs; in other words, the FCG put less emphasis on the disease itself and more on the issues the patient was experiencing because of the disease.

Multiple FCGs spoke about depression. One FCG related that when the patient found out that she needed more chemotherapy, she gave up her favorite activity—working on her car—and wanted to be left alone. Another FCG explained that having her children home from school during the summer helped to improve her husband’s mood; because he was not alone during the day, he could not dwell on his condition and physical appearance. The FCG stated that when she returned home at night from work, she did not know what kind of mood her husband would be in. Regardless of his mood, she could not share her day with him. Another FCG described her loved one as being “at a crossroad,” saying that “one minute she accepts it, and another minute she doesn’t.” Her loved one dwelled on the “why me?” question, with her moods alternating between happy and sad.

Uncertainty was another topic that FCGs raised. One FCG said that patients with cancer are never really in remission: “You can’t just tuck it away.” Another FCG used the term “emotional rollercoaster” to explain how it feels to not know about the course of the disease and the future. Several FCGs described this uncertainty as “exhausting” and “heartbreaking,” remarking on the helplessness they felt when watching their loved one suffer and being unable to relieve that suffering. One FCG said he recognized that death was inevitable and tried to live “one day at a time” because “we’re not promised tomorrow.”

The topic of role reversal arose several times. Husbands took on expanded household roles, and a daughter tried to adjust to taking care of her mother, who had always assumed the role of parent and caregiver. The daughter said it was hard to see her mother in a weakened state, adding that her mother had initially hidden the extent of her condition to avoid burdening the daughter.

When offered professional psychological assistance, patients did not always take advantage of it. One woman explained that machismo prevented her family member from accepting assistance; he claimed he could “handle it” on his own. Other patients took advantage of professional help and support groups, as well as expressed gratitude that such services were available.

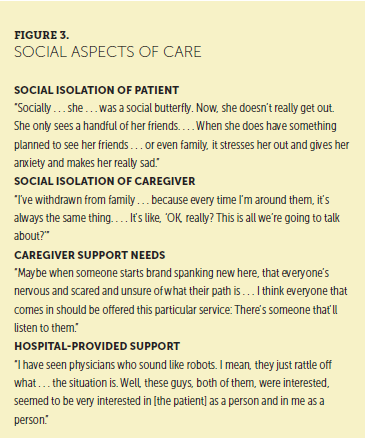

Social Aspects of Care

Social isolation was a recurring topic in FCG interviews (see Figure 3), and it was felt by the patient and the FCG. FCGs described their ill family members as being in a self-imposed social isolation, choosing not to go out when invited by friends. In addition, FCGs spoke of the stress that such invitations caused their loved ones, as well as the sadness and anxiety that accompanied plans to socialize. FCGs reported that the patients missed their work and colleagues. One FCG said the patient “misses his buddies.” A mother of a very ill daughter described her as having no social life at all:

She’s a 32-year-old woman that hasn’t had a date in three years and hasn’t had a young life. . . . Fortunately, she’s had very supportive friends, and . . . they have just been wonderful . . . in their connection with her.

In terms of FCG social isolation, one FCG stated that she had no “social needs” and that her family, which was enough of a challenge, made up her social life: “I don’t really go out and catch a movie with a friend. I don’t do any of that stuff.” Another FCG spoke of the difficulty of gauging when he could “get away” by himself, referring to the emotional state of the patient and when being away would “be acceptable.” One FCG said she had withdrawn from her family; when she was with them, all they talked about was the ill family member. She reported needing a break from caregiving responsibilities.

FCGs reported needing support and not just information: “There is nothing like having a . . . chat with someone, especially someone . . . who is sensitive, understanding, and has the experience, the depth of experience, of talking to people in all levels of . . . what they’re going through.” This FCG suggested that the healthcare community take this need into account and “handle people differently.” Another FCG echoed the same theme, saying that the details about clinical trials available online needed to be supplemented with a person who could answer questions. The FCG found the information to be confusing, overwhelming, and largely indecipherable: “It’s just a lot of literature that I have no idea about. . . . I was really honest. I said I didn’t go to med school. I don’t know what I’m reading. I need help.”

Some of the FCGs praised the support provided by hospital staff, including physicians, social workers, and nurses. Several expressed that having someone to talk to when they were scared, nervous, or unsure, such as before a computed tomography scan or other procedure, would be helpful. They complimented the City of Hope resource center and helpline telephone service, saying that these were resources they could go to for information and guidance regarding who could address their concerns. One FCG said, “I did have some issues where . . . things had gotten overwhelming . . . and they sent me to the right people.” Of the helpline, an FCG said, “We have always known we had a resource . . . out here, and we’ve used it.” Group meetings for patients made up of “either survivors or [people who are] living it” were praised as a good source of patient support. An FCG said it was nice to talk with others who had faced similar issues to know they were not alone in their feelings: “Some of your reactions are very normal, and it’s OK to have them.” In addition, FCGs found the social workers and physicians who listened to and responded to their needs to be invaluable.

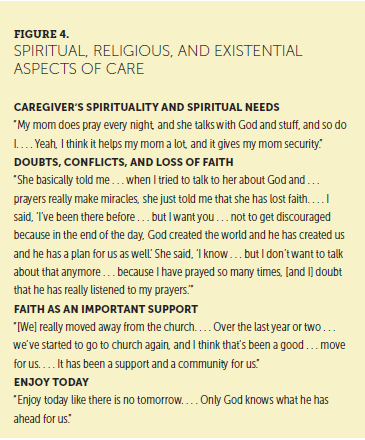

Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care

FCGs reported praying for “patience and tolerance and understanding” to help their loved ones (see Figure 4). Others expressed questions in their prayers and dismay about why their loved ones had to suffer from disease. Some stated that their family members had lost their faith and that they themselves were angry with “God’s ways.” One FCG said, “I think he forgives me for my irritation with some of his decisions.” Other FCGs expressed that they and their loved ones were relieved that there was a “God to pray to and to know that he’s listening.” One FCG stated that God answers prayers; these answers were “not always in the way you want him to . . . but he does answer.” Another FCG stated that faith was such an important support and that a “deep-seated faith” allowed her loved one to “continue on this journey and not feel the depths of despair that some people do.” The act of having faith provided a community, which was a source of support. Several FCGs voiced a “live for today” philosophy, not putting off trips or other things they wanted to do, because “only God knows what he has ahead for us.”

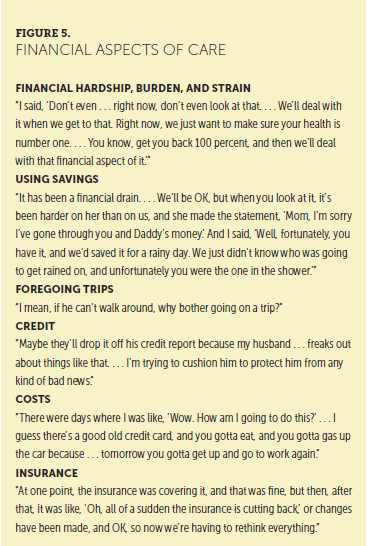

Financial Aspects of Care

Financial concerns of FCGs were plentiful. They reported the burdens, stresses, hardships, and strain that accompany illness and treatment (see Figure 5). Although a few FCGs had set aside money for emergencies such as illness or had good healthcare benefits, the majority said they were struggling, balancing disability payments with housing expenses or using savings to get by. FCGs worried about the impact of the illness on their credit or about gaps before Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program) began, which left patients responsible for co-payments or out-of-pocket expenses (“We got . . . the bill, and she had a panic attack”). The costs associated with medical care were abundant, but the most common ones reported by FCGs were the expenses associated with last-minute flights, gasoline, overnight hotel stays, restaurant meals, and vehicle maintenance. Even those who said they currently were financially stable and had healthcare coverage voiced serious anxiety about the future of healthcare coverage. Many also spoke about insurance concerns: deductibles and co-payments, sudden cutbacks or changes in coverage, or concern for the political environment that was threatening insurance, Social Security, and Medicare benefits. These considerations caused FCG distress and additional burden.

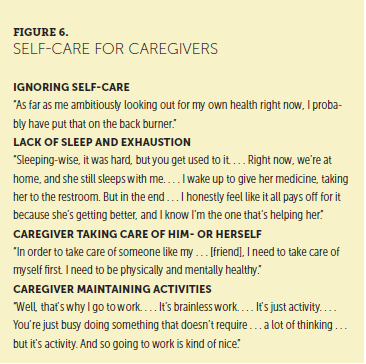

Caregiver Self-Care

Based on responses to the question of how FCGs cared for themselves, the majority of FCGs were neglecting self-care and were too busy taking care of their loved ones to care for themselves (see Figure 6). Some FCGs reported lack of sleep and exhaustion because the ill patient required their full and immediate attention. One FCG said that the hospital had not provided a cot or reclining chair when he stayed overnight with his wife, but that they were not there to take care of him: “If I had to make a choice between supreme medical care and my own comfort, I’ll take the supreme medical care every time.” Another FCG suspected that he had some health issues that needed to be addressed, but he did not want to worry his wife:

I have held off on that because . . . I wanted to make sure that I didn’t somehow find out that I have an issue that needed to be addressed, where all of a sudden my wife would be more worried about me, which would be kind of standard.

Similarly, an FCG said that “whatever medical situations” he had, they had to take care of his wife’s first.

Other FCGs recognized they needed to care for themselves to take care of their loved ones (“I knew that I had to . . . make sure that I was . . . as healthy as I could be to take care of her”), so they planned ahead for meals, exercised, went to doctors’ appointments and checkups, took walks, participated in hobbies (e.g., quilting classes), or worked, all of which served as a refuge or respite from caring.

Clinical Implications

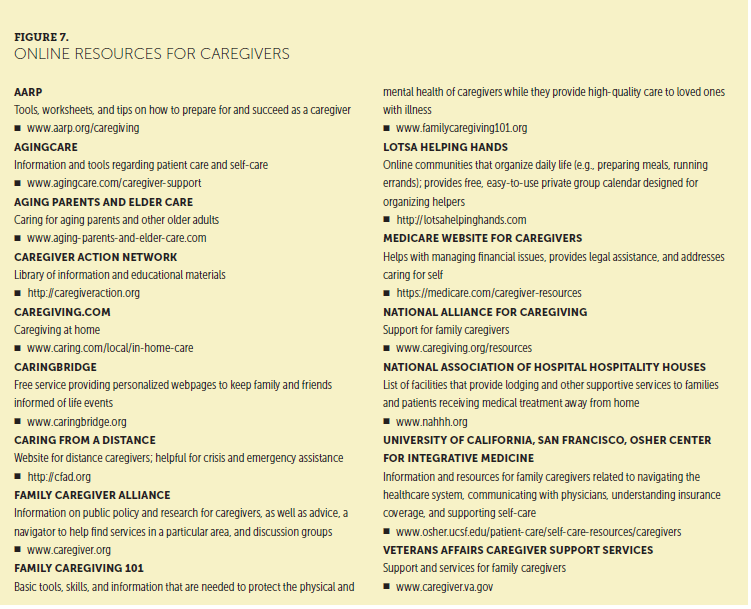

The themes identified through FCG interviews provide important direction for nursing care. In terms of physical aspects of care, it is clear that the management of patient symptoms is a key area of caregiving, as well as an area where FCGs need preparation and support. Similarly, FCGs also may be experiencing symptoms of their own, and nurses should ask FCGs about those physical needs and symptoms. In regard to psychological aspects of care, FCGs are involved with assessing and responding to the many emotions and psychological needs of the patient. FCGs also may have many emotions and symptoms, and nurses can acknowledge those concerns and encourage FCGs to seek counseling and pay attention to their own symptoms. In addition, when asked about social aspects of care, patients and FCGs voiced their need for support and other resources. Figure 7 includes some key resources that can be used by oncology nurses to support FCGs. Related to spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care, FCGs have spiritual needs and rely on their faith to support them in the difficult role of cancer caregiver. Nurses routinely ask patients if they wish to see a chaplain, but they also should be attentive to the spiritual needs and requests for chaplaincy support of FCGs. As for the financial aspects of care, FCG responses serve as a reminder that these concerns add stress to the already difficult role of caregiving. Nurses are key to assessing for financial strain and involving social workers or financial counselors. Finally, most FCGs recognize their lack of self-care. Nurses should discuss self-care needs with FCGs and direct them to all available resources.

Conclusion

From interviews with FCGs, it is evident that more attention needs to be paid to the effects of caring for loved ones with cancer. For instance, cancer exacts a financial toll, and oncology clinicians need to advocate for and provide support to help address the significant financial strain and burden that is placed on patients and FCGs. On the whole, cancer affects all quality-of-life domains for patients and FCGs. Nurses can support FCGs in caring for patients with cancer and for themselves.

About the Author(s)

Betty R. Ferrell, RN, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, CHPN, is a professor and director of the Division of Nursing Research and Education, and Kate Kravitz, RN, HNB-BS, LPC, NCC, ATR-BC, Tami Borneman, RN, MSN, CNS, FPCN, and Ellen Taratoot Friedmann, JD, are all senior research specialists in the Division of Nursing Research and Education, all at the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, CA. The authors take full responsibility for this content. This study was funded by a research grant from the American Cancer Society (principal investigator: Ferrell). The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Society. Ferrell can be reached at bferrell@coh.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2017. Accepted November 24, 2017.)

References

AARP. (2016). Caregivers and technology: What they want and need. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/home-and-family/personal-technolo…

Candy, B., Jones, L., Drake, R., Leurent, B., & King, M. (2011). Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2011, CD007617. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007617.pub2

Ferrell, B., & Wittenberg, E. (2017). A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21396

Girgis, A., Lambert, S., Johnson, C., Waller, A., & Currow, D. (2013). Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: A review. Journal of Oncology Practice, 9, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2012.000690

Given, B.A., Given, C.W., & Sherwood, P. (2012). The challenge of quality cancer care for family caregivers. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 28, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.002

Goren, A., Gilloteau, I., Lees, M., & DaCosta Dibonaventura, M. (2014). Quantifying the burden of informal caregiving for patients with cancer in Europe. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22, 1637–1646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2122-6

Hudson, P.L., Thomas, K., Trauer, T., Remedios, C., & Clarke, D. (2011). Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41, 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.006

James, E., Hughes, M., & Rocco, P. (2016). Addressing the needs of caregivers at risk: A new policy strategy. Retrieved from http://www.healthpolicyinstitute.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/Caregiver…

Kamal, A.H., & Dionne-Odom, J.N. (2016). A blue ocean strategy for palliative care: Focus on family caregivers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(3), e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.305

Kamal, K.M., Covvey, J.R., Dashputre, A., Ghosh, S., Shah, S., Bhosle, M., & Zacker, C. (2017). A systematic review of the effect of cancer treatment on work productivity of patients and caregivers. Journal of Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy, 23, 136–162. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.2.136

Kavalieratos, D., Corbelli, J., Zhang, D., Dionne-Odom, J.N., Ernecoff, N.C., Hanmer, J., . . . Schenker, Y. (2016). Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316, 2104–2114. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16840

Kent, E.E., Rowland, J.H., Northouse, L., Litzelman, K., Chou, W.-Y., Shelburne, N., . . . Huss, K. (2016). Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer, 122, 1987–1995. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29939

Li, Q., & Loke, A.Y. (2013). The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: A critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 2399–2407. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3311

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP Public Policy Institute. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united…

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2013). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (3rd ed.). Pittsburgh, PA: Author.

Nielsen, M.K., Neergaard, M.A., Jensen, A.B., Bro, F., & Guldin, M.-B. (2016). Psychological distress, health, and socio-economic factors in caregivers of terminally ill patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24, 3057–3067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3120-7

Sun, V., Grant, M., Koczywas, M., Freeman, B., Zachariah, F., Fujinami, R., . . . Ferrell, B. (2015). Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer, 121, 3737–3745. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29567

Sun, V., Kim, J.Y., Irish, T.L., Borneman, T., Sidhu, R.K., Klein, L., & Ferrell, B. (2016). Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology, 25, 1448–1455. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3987

Thomas, S., Dalton, J., Harden, M., Eastwood, A., & Parker, G. (2017). Updated meta-review of evidence on support for carers. Health Services and Delivery Research, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr05120

Zafar, S.Y. (2015). Financial toxicity of cancer care: It’s time to intervene. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 108(5), djv370. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv370

Zafar, S.Y., Peppercorn, J.M., Schrag, D., Taylor, D.H., Goetzinger, A.M., Zhong, X., & Abernethy, A.P. (2013). The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist, 18, 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279