Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice

The Professional Oncology Navigation Task Force created this document to provide professional oncology clinical navigators and patient navigators with clear information regarding the standards of professional practice. This includes the knowledge and skills all professional navigators should possess to deliver high-quality, competent, and ethical services to people impacted by cancer. These standards also provide benchmarks for use by healthcare employers and information for policy and decision makers, as well as other health professionals and the public to understand the role of professional oncology navigators. These standards are intended to provide guidance and may be applied differently, as appropriate, in different settings. These standards are designed to address professional oncology navigator practice and are not meant to apply to individuals working in a volunteer navigation role. It is important to read this document in whole and cross-reference within the document and with relevant professional guidance as necessary.

Jump to a section

Documented throughout recorded history, cancer has been called the “emperor of all maladies.”1 Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020.2 The disease can pose significant burdens to the individuals, families, and communities impacted and to the professionals and systems charged with caring for them. It taxes our individual physical, emotional, and financial capabilities, and our global systemic and financial capacities.

Cancer also has a disproportionate impact on communities of color, those with lower socioeconomic status, LGBTQ communities, and other populations who tend to experience access inequalities, lower-quality healthcare, and higher cancer death rates.3-6 The confluence of social determinants of health (which are the “conditions in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect health, functioning, and quality of life”7), systemic racism, and inadequate policy approaches have contributed to a cancer care system that produces inequitable experiences and outcomes.

Patient navigation emerged as one solution following the 1989 American Cancer Society National Hearings on Cancer in the Poor.8 The hearings highlighted the substantial barriers, pain and suffering, personal sacrifices, and discrimination many people with limited financial means face when confronted with cancer.8 In 1990, Harold P. Freeman, MD, launched the first patient navigation program in the United States based in Harlem, New York.8 Patient navigation was developed as a “strategy to improve outcomes in marginalized populations by eliminating barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment of cancer and other chronic diseases.”9

Since the founding of the first program, patient navigation has evolved, expanded, and grown and is sometimes contracted based on available support and funding. Navigation has received government attention and funding as evidenced by the Patient Navigator Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Act of 2005 and systems-level integration as evidenced by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer standard mandating navigation within accredited programs beginning in 2015. It has come to include unlicensed, nonclinical navigators as well as those with clinical nurse or social work licenses. In addition, a host of individuals fill vital roles alongside navigators in clinics, hospitals, and communities. These include community health workers, promotores/promotoras de salud, and financial navigators along with many other individuals and roles who help to navigate patients across the cancer care system.

Freeman and Rodriguez noted in 2011 that “patient navigation should be defined with a clear scope of practice that distinguishes the role and responsibilities of the navigator from that of all other providers.”8 Despite, or perhaps because of, the growth and evolution of the profession, it has historically been a moving target to define and standardize oncology navigation.

The Professional Oncology Navigation Task Force created this document to provide professional oncology clinical navigators and patient navigators with clear information regarding the standards of professional practice. This includes the knowledge and skills all professional navigators should possess to deliver high-quality, competent, and ethical services to people impacted by cancer. These standards also provide benchmarks for use by healthcare employers and information for policy and decision makers, as well as other health professionals and the public to understand the role of professional oncology navigators. These standards are intended to provide guidance and may be applied differently, as appropriate, in different settings. These standards are designed to address professional oncology navigator practice and are not meant to apply to individuals working in a volunteer navigation role. It is important to read this document in whole and cross-reference within the document and with relevant professional guidance as necessary.

Goals of the Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice

• Enhance the quality of professional navigation services provided to people impacted by cancer

• Advocate with and on behalf of people at risk for cancer, cancer patients, survivors, families, and caregivers to protect and promote the needs and interests of people impacted by cancer

• Encourage navigator participation in the creation, implementation, and evaluation of best practices and quality improvement in oncology care

• Promote navigator participation in the development, analysis, and refinement of public policy at all levels to best support the interests of people impacted by cancer and to protect and promote the profession of navigation

• Educate all stakeholders about the essential role of navigators in oncology systems

Definitions

The definitions included in these Standards reflect a select group of professional oncology navigators, including patient navigators and clinical navigators. They are not meant to apply to every specific type of oncology navigator or volunteer navigator. There may be other roles that deliver select components of patient navigation, such as financial navigation.

Professional navigator: A trained individual who is employed and paid by a healthcare-, advocacy-, and/or community-based organization to fill the role of oncology navigator. Positions that fall under the professional navigator category include oncology patient navigators and clinical navigators. Clinical navigators comprise oncology nurse navigators and oncology social work navigators.

Oncology patient navigator: A professional who provides individualized assistance to patients and families affected by cancer to improve access to healthcare services. A patient navigator may work within the healthcare system at the point of screening, diagnosis, treatment, or survivorship or across the cancer care spectrum or outside the healthcare system at a community-based organization or as a freelance patient navigator.10 A patient navigator may be employed by a clinic or a community-based organization and work throughout the community, crossing the clinic threshold to continue to provide a consistent person of contact and support within the healthcare system. A patient navigator does not have or use clinical training.

Clinical navigator/oncology nurse navigator: A professional registered nurse with oncology-specific clinical knowledge who offers individual assistance to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome healthcare system barriers. Using the nursing process, an oncology nurse navigator provides education and resources to facilitate informed decision-making and timely access to quality health and psychosocial care throughout all phases of the cancer continuum.11

Clinical navigator/oncology social work navigator: A professional social worker with a master’s degree in social work and a clinical license (or equivalent as defined by state laws) with oncology-specific and clinical psychosocial knowledge who offers individual assistance to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome healthcare system barriers. Using the social work process, an oncology social work navigator provides education and resources to facilitate informed decision-making and timely access to quality health and psychosocial care throughout all phases of the cancer continuum.

Oncology navigation: Individualized assistance offered to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome healthcare system barriers and facilitate timely access to quality health and psychosocial care from prediagnosis through all phases of the cancer experience.11-13

Patient: In this document, patient is used to refer to an individual screened for or diagnosed with cancer, as well as their family and support systems. When working with children with cancer, both the child and the parent/legal guardian are incorporated into all aspects of care, including decision-making.

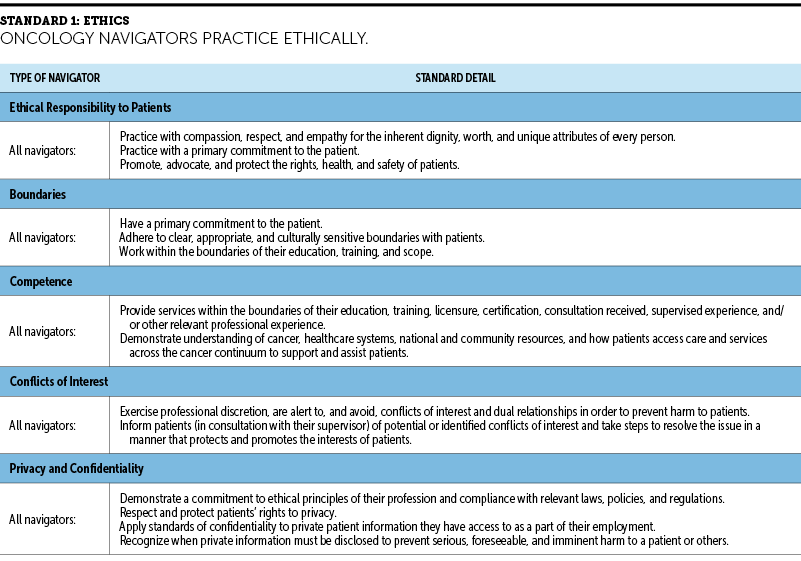

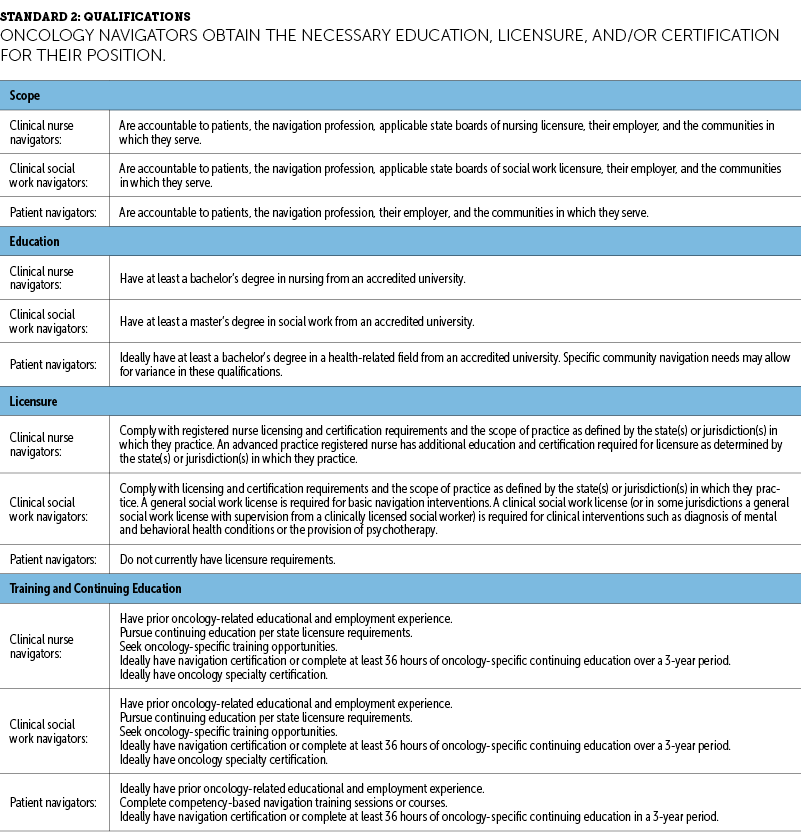

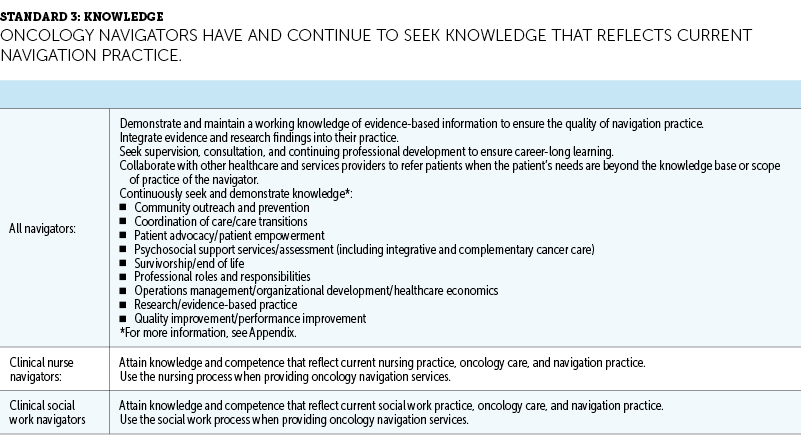

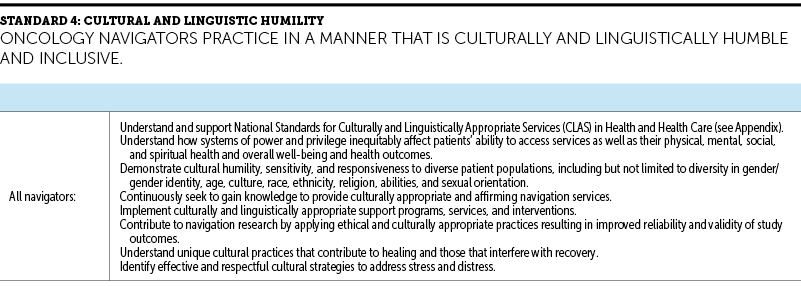

Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice

The Oncology Navigation Standards of Professional Practice identify best practices to promote a high level of navigation quality. They are intended to serve as guidance for professional practice (regardless of setting). Exceptions to the Standards may be necessary and should be determined on an individual or institutional basis. The following standards apply to all 3 types of professional navigators unless otherwise noted below.

Knowledge Resources

Scope and Standards of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nursing Practice. Chicago, IL: Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses; 2014.

Christensen D, Cantril C. Oncology Nurse Navigation: Delivering Patient-Centered Care Across the Continuum. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2020.

GW Cancer Center. Oncology Patient Navigator Training: The Fundamentals. https://cme.smhs.gwu.edu/gw-cancer-center-/content/oncology-patient-nav….

Pratt-Chapman ML, Willis A, Masselink L. Core competencies for oncology patient navigators. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2015;6(2):16-21.

Shockney LD (ed). Team-Based Oncology Care: The Pivotal Role of Oncology Navigation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018.

US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdfs/EnhancedNationalCLASSta….

Acknowledgments

The professional organizations responsible for the creation of the Oncology Navigation Standards for Professional Practice include the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators, Association of Oncology Social Work, Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses, and Oncology Nursing Society. The patient organizations involved in the creation of this document include the Cancer Support Community and the Smith Center for Healing and the Arts. The initial work of the Biden Cancer Initiative working group on patient navigation also led to the creation of this document. We would like to thank all individuals and organizations who reviewed and commented on this document.