Consent and Assent in Pediatric Research: Whose Right Is It Anyway?

Although the right to health care is not written into the U.S. Constitution, moral and ethical tenets govern the delivery of optimal medical care universally and across the life continuum. Pertaining to children, in accordance with the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1924 and the United Nations Human Rights General Assembly adoption of the Rights of the Child in 1959, parents or guardians are responsible for the health and well-being of a child until age 18 years. Much consideration is needed regarding the anatomic, physiologic, emotional, and cognitive development of children when making decisions regarding their health care and, particularly, when enrolling them into research studies.

Jump to a section

Although the right to health care is not written into the U.S. Constitution, moral and ethical tenets govern the delivery of optimal medical care universally and across the life continuum (De Lourdes Levy, Larcher, & Kurz, 2003). Pertaining to children, in accordance with the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1924 and the United Nations Human Rights General Assembly adoption of the Rights of the Child in 1959 (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 1990), parents or guardians are responsible for the health and well-being of a child until age 18 years. Much consideration is needed regarding the anatomic, physiologic, emotional, and cognitive development of children when making decisions regarding their health care and, particularly, when enrolling them into research studies.

Guidelines encourage alternatives to conducting research on participants younger than age 18 years, when possible (Gill et al., 2003). In recognition of how children differ from adults with their varying stages of development, it is not always possible to simply apply results from adult studies to children. Regulations are in place, however, to not only minimize risks to pediatric research participants, but also ensure that such risks are less than those taken by adult research participants (Diekema, 2006). When it is necessary to conduct research on children, the usual protocol is for parents or guardians to consent as proxies (Leibson & Koren, 2015) and for children to give assent starting as young as age 7 years (National Cancer Institute, 2014). Assent is the child’s agreement to participate in the study. Ideally, the discussion with the child is conducted during several sessions before the research team feels confident that the child understands what study participation will entail and agrees to participate (National Cancer Institute, 2014). However, challenges arise when the parent or guardian and child have differing wishes. In addition, considerations are needed in situations where children may be more educated than adults, which is sometimes the case in disparate communities. Assent issues are compounded when the study involves genetic and genomic investigations. Anyone conducting research in individuals younger than age 18 years should consider these factors.

Evaluating Children’s Rights and Capacity

Researchers generally assume that adults are informed and have the capacity to make decisions for and in the best interest of children. Researchers also think that children are not cognitively mature enough to have autonomous authority (De Lourdes Levy et al., 2003). In fact, the impetus for the adult consenting process for children is under the premise that children are a vulnerable population, with such populations protected under the Declaration of Helsinki (Leibson & Koren, 2015; World Medical Association, 2013). Morally and ethically, respecting children’s rights to agree to participate should be considered to the fullest extent possible (Gill et al., 2003). Planning research studies in pediatric populations necessitates determining the earliest age at which children can accurately understand, appreciate, reason, and choose whether or not to participate in a study. Hein et al. (2014) adapted a version of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research and found that children were competent enough to make that type of decision beginning at age 9.6 years. Of note, this finding is older than the general guideline of age 7 years. Understanding that children might mature at younger or older ages, all children should be included in the decision-making process whenever possible.

When talking with children about a research study, researchers should recognize that children often align with their parents’ or guardians’ beliefs, values, and wishes at a young age but may develop differing opinions as they get older (Leibson & Koren, 2015). When the parent or guardian and a child have differing opinions about enrolling in a study, researchers should always take the child’s wishes seriously and evaluate the medical necessity. For example, would the child’s life or well-being be in jeopardy, and is the only treatment option to enroll in a clinical trial? If a parent or guardian consents for a child, but the child strongly dissents, evaluate the child’s cause for dissent (e.g., misunderstanding the study, does not like what is involved in the study, does not want to be taken from school) (Cheah & Parker, 2014). If the child assents but the parent or guardian dissents, ensure that the parent or guardian understands the importance of the study, and evaluate the decision, whether it may be against cultural beliefs, a time burden, or some other factor. In addition, in situations where research studies are targeted at underserved, disparate populations with high incidence and prevalence rates of specific diseases that necessitate investigation, educating the adults and children is a priority (Cheah & Parker, 2014).

In all settings, thorough education for adults and children cannot be overemphasized when children are sought for genomic studies. The ethical issues surrounding adult participation in genomic studies is complex because of disclosing findings to family members, making decisions about incidental findings that can affect patients and family members, properly interpreting unclear results, and addressing confidentiality issues (Wilfond & Diekema, 2012). With children, the complexity increases tremendously. Some of the challenges include disclosing findings to children once they are aged 18 years, implications for them as children depending on the findings, and consequences for potential future offspring (Wilfond & Diekema, 2012). Overall, the level of understanding for adults and children regarding genomic studies may be minimal. When possible, the consent and assent processes should include a form of additional written material that simplifies the study information (Leibson & Koren, 2015; National Cancer Institute, 2014; Wilfond & Diekema, 2012).

Questions to Consider

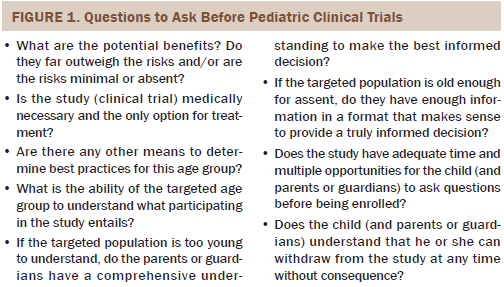

With the evolving complexities of research science involving children, some basic guidelines can help ensure that benefit is high and risk is minimal, that parents or guardians and children understand the study to the best of their abilities, and that conducting the research study will provide important and clinically meaningful outcomes. Simple questions can be asked when conducting a pediatric research study (see Figure 1).

Conclusion

Enrolling children into research studies is complex and necessitates moral and ethical considerations. Taking time to ensure that parents or guardians and children fully comprehend the scope of what is involved is paramount. With the unfolding genomic science that often benefits from children enrolling in research studies, the guidelines and parameters for consent and assent will likely shift to meet these needs and challenges. Genomic discoveries will hopefully reduce the amount of studies needed in the pediatric population.

References

Cheah, P.Y., & Parker, M. (2014). Consent and assent in paediatric research in low-income settings. BMC Medical Ethics, 15, 22. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-15-22

De Lourdes Levy, M., Larcher, V., & Kurz, R. (2003). Informed consent/assent in children. Statement of the Ethics Working Group of the Confederation of European Specialists in Paediatrics (CESP). European Journal of Pediatrics, 162, 629–633. doi:10.1007/s00431-003-1193-z

Diekema, D.S. (2006). Conducting ethical research in pediatrics: A brief historical overview and review of pediatric regulations. Journal of Pediatrics, 149(Suppl.), S3–S11. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.043

Gill, D., Crawley, F.P., LoGiudice, M., Grosek, S., Kurz, R., de Lourdes-Levy, M., . . . Chambers, T.L. (2003). Guidelines for informed consent in biomedical research involving paediatric populations as research participants. European Journal of Pedatrics, 162, 455–458. doi:10.1007/s00431-003-1192-0

Hein, I.M., Troost, P.W., Lindeboom, R., Benninga, M.A., Zwaan, C.M., van Goudoever, J.B., & Lindauer, R.J. (2014). Accuracy of the MacArthur competence assessment tool for clinical research (MacCAT-CR) for measuring children’s competence to consent to clinical research. JAMA Pediatrics, 168, 1147–1153. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1694

Leibson, T., & Koren, G. (2015). Informed consent in pediatric research. Paediatric Drugs, 17, 5–11. doi:10.1007/s40272-014-0108-y

National Cancer Institute. (2014). Children’s assent. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/patient-sa…

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (1990). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/crc.pdf

Wilfond, B.S., & Diekema, D.S. (2012). Engaging children in genomics research: Decoding the meaning of assent in research. Genetics in Medicine, 14, 437–443. doi:10.1038/gim.2012.9

World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310, 2191–2194. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053

About the Author(s)

Hammer is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing at New York University in New York. No financial relationships to disclose. Hammer can be reached at marilyn.hammer@nyu.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org.