Nursing Care at the Time of Death: A Bathing and Honoring Practice

Purpose/Objectives: To explore family members’ experience of a bathing and honoring practice after a loved one’s death in the acute care setting.

Research Approach: A descriptive, qualitative design using a semistructured telephone interview script.

Setting: The Inpatient Adult Oncology Unit at Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital in California.

Participants: 13 family members who participated in the bathing and honoring practice after their loved one’s death on the oncology unit.

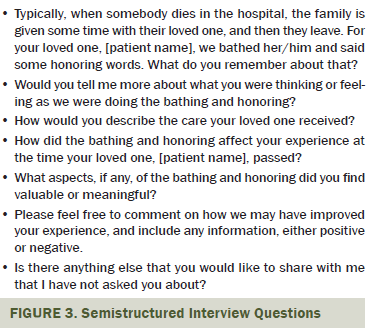

Methodologic Approach: Participants were selected by purposive sampling and interviewed by telephone three to six months after their loved one’s death. Interviews using a semistructured script with open-ended questions were recorded, transcribed, verified, and analyzed using phenomenologic research techniques to identify common themes of experience.

Findings: 24 first-level themes and 11 superordinate themes emerged from the data. All participants indicated that the bathing and honoring practice was a positive experience and supported the grieving process. The majority found the practice to be meaningful and stated that it honored their loved one. Many expressed that the bathing and honoring was spiritually significant in a nondenominational way and that they hope it will be made available to all families of patients who die in the hospital.

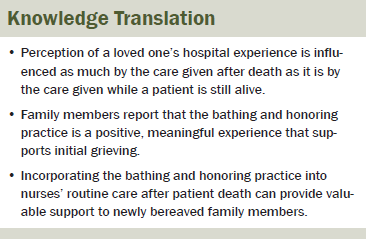

Conclusions: After patient death, a bathing and honoring practice with family member participation is positive and meaningful, and it supports family members’ initial grieving.

Interpretation: This study is a first step toward establishing specific nursing interventions as evidence-based practice that can be incorporated in routine nursing care for patients and families at the end of life.

Jump to a section

According to statistics published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011), more than one-third of the population dies in acute care hospitals, and about 20% die in nursing homes. Nurses are the primary bedside healthcare providers in these settings, and they care for patients leading up to and at the time of death. Providing competent, compassionate care to patients and their families throughout the course of illness, including after a patient dies, is an important part of nurses’ work. Oncology nurses, in particular, are committed to providing the best possible care to their patients and patients’ families at end of life (Beckstrand, Collette, Callister, & Luthy, 2012)

Pattison (2008b, p. 55) described nursing care of the patient who has died as “the final act of caring” and stressed that families often have vivid memories of the events surrounding the death and the care given afterward. From family members’ point of view, perception of their loved one’s hospital experience is influenced as much by the care given after death as it is by the care given while the patient is still alive. End-of-life nursing education (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2016) and practice guidelines (AACN, 1998; Dahlin, 2013; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2013) establish the importance of competent, compassionate care by nurses after death. Although some mention exists in the literature of bathing the deceased and the use of ritual to support grieving in bereaved family members as part of that care (Moules, Simonson, Prins, Angus, & Bell, 2004; Olauson & Ferrell, 2013; Pattison, 2008a, 2008b), research studying specific nursing interventions is nascent (Thirsk & Moules, 2013). This article reports the results of a qualitative research study that explored family members’ experience of a bathing and honoring practice after the death of their loved one on an oncology unit in an acute care hospital.

Methods

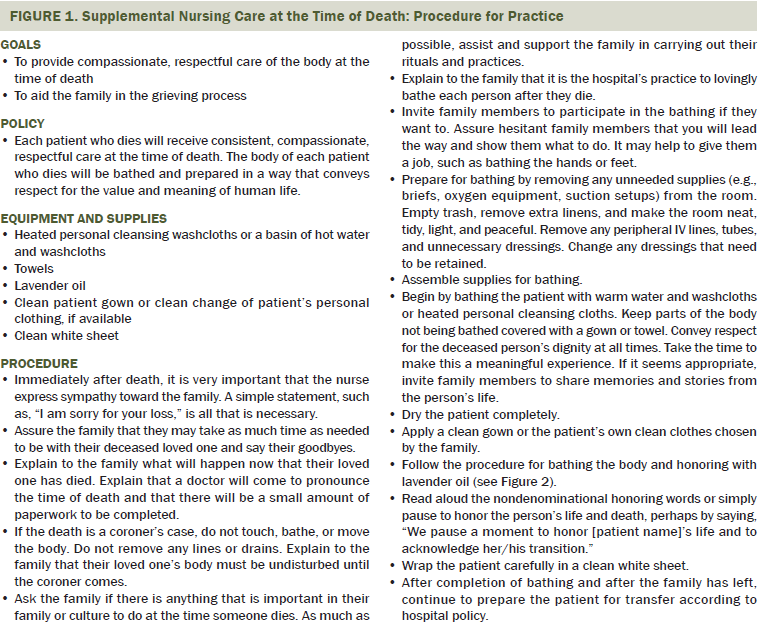

A procedure (see Figure 1) has been developed to bathe and honor patients with the recital of nondenominational words for those who die in the acute care setting. While the honoring words (see Figure 2) are being read, lavender oil is placed on the patient. A Spanish translation of the procedure is available.

Approval was obtained from the institutional review board at Cottage Health System in Santa Barbara, California, prior to the start of this research study, including approval to obtain verbal consent from family members to perform the bathing and honoring practice and to conduct subsequent telephone interviews. All disciplines involved in end-of-life care on the oncology unit were trained in the bathing and honoring practice during a four-hour training session. This included nurses, patient care technicians, palliative care providers, interpreter services, spiritual care staff, and social workers.

The bathing and honoring practice was offered to all families of patients who died on the oncology unit during the course of the study from February 2011 to June 2013. When family members left the hospital, they were given a letter stating that they may be contacted with questions about their experience. A log was maintained by the charge nurse documenting whether the bathing and honoring practice was performed and, if it was not, the reason.

When a patient dies on the oncology unit, the nurse asks if there is anything that is important in their family, culture, or faith to do when someone dies. If there is, the nurse supports the family to do those things in the hospital as much as possible. The nurse also explains that it is the oncology unit’s practice to give each patient who dies a last, loving bath and asks if the family would like to take part. If the family agrees, they are invited to participate in the bathing to the extent that they feel comfortable. Sometimes, family members just observe staff bathing their loved one, and, other times, family members wash their loved one’s face, hands, and feet. Still others bathe their loved one thoroughly in an unhurried way, with caring attention given to each part of the body. In the second part of the bathing and honoring practice, nondenominational words are read by a nurse, chaplain, or family member while the nurse and/or family members rub lavender oil on their loved one’s skin. Throughout the practice, nurses invite family members to share stories and memories of their loved one.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"23496","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"628","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"366"}}]]

Data Collection

Family members who participated in the bathing and honoring practice were selected to be interviewed by purposive sampling based on their willingness to provide contact information and to talk at length with researchers about their experience (Polit & Beck, 2012). Participants were eligible for interviewing if they were aged 18 years or older and were present for the bathing and honoring practice on the oncology unit. The interview questions were focused on learning the lived experience of family members based on a descriptive, phenomenologic research approach (Polit & Beck, 2012). Data collection occurred through a semistructured interview process that allowed the interview to go in the direction determined by the interviewee (see Figure 3). Interviews were recorded using a digital voice recorder and uploaded to a password-protected data storage folder on the hospital’s primary server. One investigator transcribed the interviews verbatim, and a second investigator independently verified them for accuracy. Interviews were conducted until saturation was reached and no new themes emerged.

Data Analysis

Three co-investigators analyzed the interviews to identify emerging themes. Data analysis followed a phenomenologic analytic method, as described by Polit and Beck (2012). Polit and Beck (2012) listed four steps of descriptive phenomenology: bracketing, intuiting, analyzing, and describing. In the first step of bracketing, co-investigators identified their preconceived beliefs that the bathing and honoring practice was beneficial and supportive, setting those beliefs aside to hear the participants’ experience as impartially as possible. The co-investigators independently listened to the recordings and read the transcripts while making initial notation of thoughts and feelings expressed by the participants relating to the bathing and honoring practice, intuiting first-level emerging themes. The investigators then met, discussed their notes, and confirmed the first-level themes that had emerged, achieving inter-investigator agreement.

Investigators analyzed first-level themes, searched for connections, and grouped them into superordinate themes in an iterative process that included returning to the original recorded interviews and transcripts for confirmation. Therefore, the superordinate themes were discovered collaboratively based on patterns that emerged from the interviews. The investigators reread the transcripts and extracted quotes associated with the themes. Based on the superordinate themes, researchers formulated an integrated description of the phenomenon under study: the participants’ experience of the bathing and honoring practice.

Rigor

Koch (2006) suggested that, to establish rigor in qualitative research, the researcher must show evidence of credibility, transferability, and dependability. Credibility can be established by returning to the participants for validation of coded themes or by enlisting other readers to offer evaluation and outside perspective on interpretation (Koch, 2006; Moules, 2002). Credibility can also be supported by one or more kinds of triangulation (Carter, Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Blythe, & Neville, 2014; Guion, Diehl, & McDonald, 2002). Cooney (2011) further defined credibility in qualitative research as referring to how vividly and faithfully the research describes the phenomenon. When qualitative research is credible, participants, researchers, and practitioners recognize the experience, and “the reader should ‘almost literally see and hear the people’” (Cooney, 2011, p. 19).

Sensitive to the feelings of grief that could be triggered by additional contact with interview participants, researchers chose instead to use internal triangulation of investigators and external triangulation by different readers to establish credibility. External triangulation was established by nurses with advanced degrees within the hospital who were not on the research team.

As bedside nurses conducting research, it was important to reach out and elicit the expertise of doctoral-prepared nurse researchers and academic leaders. Early on, one academic nurse leader who specialized in the development of evidence-based practices evaluated the data collection and analysis, essentially auditing the process from transcription of interview recordings through the three steps of coding and selection of interview quotes to support emerging themes. In addition, this academic nurse leader and a second doctoral-prepared academic nurse reviewed the article for accuracy and rigor.

Transferability refers to the concept that research findings can by transferred to settings other than the study environment and that readers will find the results meaningful and appropriate based on their own experiences (Koch, 2006; Moules, 2002). During the course of the study, researchers presented preliminary findings internally within the organization and externally at two End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) Summits. Within the hospital, two intensive care units and a medical and surgical unit chose to adopt the bathing and honoring practice, adapting it to their patient care environments with good result. Externally, the bathing and honoring practice was extremely well received by participants from a wide variety of practice settings at both ELNEC Summits and earned a 2013 ELNEC Award of Excellence for contribution to hospice and palliative care.

Dependability is achieved by “exact documentation of the process of inquiry in such a way that demonstrates how interpretations have been arrived at” (Moules, 2002, p. 16). Selected quotes from the transcripts reflect the identification and interpretation of themes transparently in a way that allows the reader to confirm the findings.

In addition to credibility, transferability, and dependability, Moules (2002) stated that the rigor of a qualitative study is bolstered when the research is consistent with the philosophical ground on which it is based. This study achieves consistency by expanding on evidence found in the literature and by relating findings to Watson’s Theory of Caring (Watson Caring Science Institute, 2016) and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (Dahlin, 2013).

Findings

During two years and three months, 149 patients died on the oncology unit. Of those who were offered the bathing and honoring practice, 89 families (68%) chose to participate. Thirteen interviews were conducted, and permission to record telephone interviews was obtained. Data on why families declined participation were not systematically collected, but nurses noted that some families did not feel comfortable participating, were not present, or stated the patient would not want the bathing and honoring practice.

Six families were not offered the bathing and honoring practice; in one instance, staff was unavailable, and the others were prohibited because they were coroner’s cases. The oncology unit cares for overflow medical and surgical patients when beds are available and, of the five coroner’s cases, two were patients who had been in motor vehicle accidents, one was a suspected suicide, and the remaining two patients died within 24 hours of admission to the hospital, triggering coroner review.

Eleven superordinate (second-level) themes emerged from the initial first-level coding of 24 themes. Superordinate themes were then ranked by the number of interviews in which they were mentioned and the total times mentioned in the interviews. The top five themes are discussed in detail in the current article.

Positive Experience

In all of the interviews, without exception, participants expressed that the bathing and honoring practice was a positive experience. A total of 86 different statements were made using a variety of superlative adjectives in which interviewees communicated their appreciation of the practice and the experience. They described it as tasteful, respectful, beautiful, incredibly thoughtful, absolutely wonderful, amazing, and impressive, and they said they were very happy they had participated. One participant said, “It was a good experience for me.” Another noted, “I left glad that I was participating and that I was there for that. . . . It was a positive experience.” A different participant said, “I thought so much of the way it was done . . . and how we participated. . . . Everybody felt pretty complete about it.”

Supported Grief Process

All 13 participants indicated that the bathing and honoring practice supported their grieving. Five themes were identified in this category: (a) evoked and supported emotion, (b) gives direction, (c) helped with grieving, (d) helped understand reality of a loved one’s death, and (e) facilitated transition.

Evoked and supported emotion: One participant remembered feeling a great sense of relief that the practice was going to happen. Several family members talked about the poignant feelings that arose during the bathing and honoring practice. They indicated that it evoked and supported their emotions, stating “it made me cry,” “it brought peace,” “it was comforting,” “it was very poignant,” and “I left feeling good.” Another participant said, “There’s just so many emotions around it,” and one said, “I think, like, it . . . gave a sense of peace that . . . I may not have experienced without it.”

Gives direction: Eight individuals conveyed that the bathing and honoring practice gave direction at a time when they felt lost and did not know what to do. One participant said, “At the time, you’re just kind of lost, and you don’t know what to do. And this brought a little bit more order to things.” Another participant said, “People just don’t know what to do; they’re almost frozen in their bodies.” A participant also noted, “It felt like a nice ritual . . . to perform at that time . . . because you don’t really know what to do or what to say.”

Helped understand reality of a loved one’s death: Participants expressed that it helped them to understand the reality of their loved one’s death in a very concrete way. The physicality of bathing and the review of their loved one’s life facilitated by the honoring words seemed to help family members come to terms with that reality. One participant said, “It did kind of add to the reality and the closure of it.” Another said, “I was thinking how this is my last time I would ever see him in his body.”

Facilitated transition: Some specifically said that it gave them a way to say goodbye and make the transition to finally leave their loved one. This was corroborated by nurses’ subjective observations that families tend to leave soon after the bathing and honoring practice ends, whereas, prior to implementation of the bathing and honoring practice, family members would often linger for a long time after their loved one’s death, finding it difficult to leave. One participant noted that it was “such a great way to finally . . . say your last goodbye to someone you love so dearly.” Another said, “It helped make the transition. . . . We had to . . . finally, you have to leave her.”

Meaningful

In addition to all 13 family members finding the bathing and honoring practice to be a positive experience, 12 verbalized that the bathing and honoring practice was meaningful. The honoring words resonated with participants and led them to think about personal memories and their loved one’s specific, unique qualities. Family members appreciated the lavender oil and reported using it later to comfort themselves. The bathing and honoring practice made a lasting impression, and the participants conveyed they would always remember the experience. Family members also felt honored to have been invited to participate in the practice. Five subthemes were included in this theme: (a) words and oil, (b) meaningful, (c) lasting impression, (d) final loving act, and (e) valued family participation.

Words and oil: Family members were offered a printed copy of the honoring words and the vial of lavender oil to take home. Many interviewees talked about keeping the honoring words and oil and using the oil to remember their deceased loved one and to comfort themselves. One participant said, “Some of the words rang so true.” Another said, “It was beautiful, and I still have the poem. I still have the oils, and that experience was absolutely so beautiful.” A different participant noted, “The oil , that’s huge. . . . I mean, I think you guys have really thought through. To have that oil is incredible. I have it in a special place right by my bed.”

Meaningful: Many family members spoke directly about how much the bathing and honoring practice meant to them. One participant said, “It was very meaningful,” and another said, “I thought the service was very touching. For me, it meant a lot.” A different participant said, “It just made me feel really touched that he was being honored, that he was being loved and taken care of.”

Lasting impression: Some interviewees talked about how strong their memories of the bathing and honoring practice were. One participant said, “It was an experience that I will always remember, and I wish more people would do it, [that] more hospitals actually would do that.” Another participant said, “I remember specifically how they cleaned the various parts of the body.”

Final loving act: Several family members expressed gratitude for the opportunity to perform a final loving act for their loved one. A participant noted that it was “such a great way to finally say your last goodbye to someone you love so dearly.” Another said, “Well, I guess you could say it was my last chance to honor her.”

Valued family participation: Some interviewees talked about how much they appreciated being offered to participate as family members and about how it was meaningful to them as a family. One participant said, “They honored us too because we were all a part of that person. Not only did they honor him, but they honored us.” Another said, “Thanks to the nurses, that gave me and my family the opportunity to see and experience something so personal.” A participant also noted, “That . . . was a great gift that the nurses gave to my family and myself.”

Honored Loved One

The majority of the participants stated that the practice honored their loved one, their memory, and their physical body. The bathing and honoring practice caused family members to reflect on their loved one’s life. Many volunteered memories of things their loved one had done and the kind of person they had been. It also caused family members to reflect on their own relationship with their loved one. One participant joked, “His brow . . . I helped put those wrinkles there!” Three themes emerged in this category: (a) honored their loved ones, (b) caused reflection of loved one’s life, and (c) caused reflection on own relationship with loved one.

Honored their loved ones: One participant said, “It did honor him. I think it paid tribute to my father, to the person he was.” Another said, “It seemed to just honor her memory and her physical body.”

Caused reflection of loved one’s life: A participant noted, “It really gave me pause to reflect back on his life, a life well lived. What a life well lived; what a great man.” Another said, “That was a beautiful way to spend time with who he was. Such a strong, strong man, a World War II veteran. He just worked so hard in his life.” A different participant said, “Because . . . especially the anointing of the lips . . . and what they said . . . I added more to it [laughs] because John was a jokester.”

Caused reflection on own relationship with loved one: One participant said, “His shoulders . . . beared the weight of the world, which he really did at the end.” Another said, “He just worked so hard in his life, and he just never allowed anybody to get close to him.”

Ritually or Spiritually Significant

Eleven family members made comments that indicated the bathing and honoring practice was ritually or spiritually significant to them. Some specifically used the word “spiritual,” including a few that related it to their personal religious faith. Others described it as nondenominational or ecumenical. However participants experienced this aspect of the practice, they communicated that it was positive and significant.

It seemed that individuals with a religious faith or sense of spirituality experienced the bathing and honoring practice as religious or spiritual within the context of their beliefs. One participant said, “It was my last chance to honor her by washing her feet. As a Christian, washing someone’s feet is very honorable.” Another said, “We’re all very spiritual, and that was important to us.” A different participant said, “I mean, it was spiritual. I found it very spiritual and very comforting.” A different participant said, “This is what we’ve done for thousands of years. That’s what the Middle Eastern countries do. That’s what India, the third-world countries, they all do this.”

Participants who did not have a religious orientation experienced it as a secular, human honoring. One participant said, “What I did like about it was that it was not any one particular religion. It was pretty nondenominational.” Another said, “It’s not a religious ceremony; it’s just a way to honor them.” A different participant noted, “I don’t think it had anything to do with whatever denomination you were in any way.”

Nurses’ Caring

Family members across the board spoke about how touched they were by the nurses’ genuine caring for their loved one as an individual and not just as “a patient number.” They used adjectives like “kind,” “respectful,” “gentle,” “calm,” and “personal” to describe nurses’ caring behaviors. One family member stated, “It was pretty miraculous looking up and seeing tears in the eyes of the people that did this every day.” In addition, several individuals expressed that the nurses were not only honoring their loved one who had died, but also were honoring and caring for them as family members.

Physicality

Many people spoke to the physicality of the bathing and honoring practice. Several commented on the physical act of bathing and touching different parts of their loved one’s body. They felt it honored each part of their loved one’s body, as well as the whole person. Several individuals expressed feeling very comfortable touching their loved one’s body, indicating that the practice allowed them to feel OK doing so. One woman experienced the practice as an opportunity to show her mother’s body gratitude and to give thanks for holding her mother’s spirit for so long.

New Experience

Eight of 13 participants commented on the unexpectedness of the practice, saying it was something they had never experienced before and that, in general, they did not know what was done after someone died in the hospital. All who noted the newness of the experience said that they enjoyed it, that it was a special gift, and that they were glad they participated. One person said, “It was an unexpected and very beautiful surprise.”

Another family member commented that he initially felt some hesitation about the practice. After experiencing it, he said, “I went into it thinking, ‘This is a little too much outside my comfort zone,’ but, at the end, I really was glad.”

A third participant expressed that the bathing and honoring practice had a profound effect on her, making her less afraid of dying. She said, “I’m not afraid of it anymore, for myself, for my children, for anything. I’m just not afraid.”

Hope That Bathing and Honoring Becomes Routine Care

In three interviews, the participants talked about their positive experience of the bathing and honoring practice and volunteered that they hope it will continue to be offered to families and become part of routine care. One participant said, “That is a beautiful tradition that I hope will always continue because it brought such great joy and comfort and love that I was able to share with all my family members.”

Discussion

This descriptive, phenomenologic study explored family members’ experience of the bathing and honoring practice after their loved one’s death on an inpatient oncology unit. Patients’ families unanimously reported positive responses to the bathing and honoring practice. Family members stated that the practice was a positive experience, helped with their grieving, was meaningful, was ritually or spiritually significant, and honored the deceased. The practice served its intended purpose by providing a positive and meaningful experience for families during a difficult time. Although other studies have described the benefits of care after death, this is the first comprehensive study of a specific practice of bathing and honoring in the acute care setting after a patient death.

The literature review revealed that nursing interventions at the time of death have not been extensively researched. Some of the published works on the subject are general articles on recommended practices for dying patients and their grieving families. Pattison (2008a, 2008b) encouraged nursing practices of caring for patients after death, describing bathing and dressing the patient, as well as supporting grieving family members who may have their own religious or cultural practices. Pitorak (2003) discussed the dying process and managing distressing symptoms while supporting family members leading up to death, and recommended creating rituals for after the patient dies.

Moules, Simonson, Prins, Anugs, and Bell (2004) have studied grief and therapeutic interventions nurses can use to support bereaved family members, including challenging problematic beliefs and using maps drawn of their own experiences rather than traditional grief models to guide their interactions (Moules, Simonson, Fleiszer, Prins, & Glasgow, 2007). In another study, Olauson and Ferrell (2013) explored nurses’ perceptions of caring for a patient’s body after death. This study of the bathing and honoring practice contributes a specific intervention that nurses can provide for grieving families that fills the void of recommended care after a patient dies.

Grief and the role health professionals play in treating the bereaved is a very active field of research. Worden (2009) describes grieving as a method of developing a continuing bond with the deceased. Moules et al. (2007) explain that grief is a “lifelong event and a continued connection to the lost loved one” (p. 118). The authors believe the bathing and honoring practice described in the current article supports the beginning of the grieving process by acknowledging that the loved one has passed and allowing the family to remember who he or she was as a person.

The literature in the field of grief therapy widely supports rituals to assist the bereaved in their experience of grieving. Rando (1985) described traditional funerals as rituals that serve to confirm the reality of the death of the loved one and to provide a time and place to express memories and feelings of loss while being supported by others. Rando (1985) also traced the development of modern secular rituals, which are often highly individualized and can be found in many settings. The structured nature of ritual, with a beginning, an end, and a clear focus is “especially helpful for the confusing disorganization and loss of control commonly experienced in grief” (Rando, 1985, p. 239). Rando (1985) also noted the concrete, in-the-body learning that ritual facilitates:

Participation in ritual assists one in “learning” that the deceased is gone. It provides the experience necessary to validate the loss and help the individual to prepare for, as well as make, readjustments to the environment in which the deceased is missing. (p. 239)

Running, Tolle, and Girard (2008) confirmed the ways in which grief rituals help family members or loved ones of someone who has died, calling such rituals “the final expression of care” (p. 303). They emphasized that grief rituals do not necessarily need to be culturally dependent or religious, and that secular rituals can be just as meaningful and helpful.

The authors believe that a need exists for grief support in the acute care setting and developed the bathing and honoring practice for this purpose. Participants expressed themes that are supported by the grief therapy literature, including facilitating the realization that their loved one has passed and providing a meaningful way to remember them.

Implications for Future Research

Further research is needed to substantiate the results of this study. The limitations of this study include that it was a single-institution study and that the family members interviewed were self-selected by answering the telephone when contacted and agreeing to participate. Oncology nurses often have ongoing relationships with their patients and patients’ families, which may be different than other settings within an acute care hospital, where patients may be admitted and die quickly before developing a relationship with caregivers. Studies are needed to test whether the results in this study can be replicated in other acute care environments.

Although it was not the main focus of this study, some nurses who participated wrote brief field notes documenting their observations and experience. Several nurses reported feeling honored to be a part of patients’ care during the practice. One reported that it was a concrete way to express her condolences to the family for their loss. She said, “It was one last thing we could offer the patient and the family.” Another nurse said, “This seemed to be a very cathartic experience for the patient’s sister and for myself. I am very happy to have been able to be a part of this experience.” Research into the effect the practice may have on nurses and their grieving for patients may provide insight into how nurses cope with patient deaths.

Although the 89 families who participated in the bathing and honoring practice represented a wide diversity of religious, ethnic, and national backgrounds, exploring the experience in a cultural context was not a stated objective of this study. The authors observed anecdotally that the practice was well received by all of the families regardless of culture and ethnicity. Although this information was not tracked for this study, it is an important area for further research.

Implications for Nursing

This research provides evidence that the practice is well received by families of the recently deceased and is a positive, meaningful experience that supports their initial grieving. Nurses looking for resources on care after patient death can take the information in this article and implement a positive experience for the grieving families of their patients. The practice aligns itself well with guidelines and recommendations from a diverse group of professional organizations, and many disciplines were involved with the implementation of the practice for the purposes of this research.

The bathing and honoring practice meets the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (Dahlin, 2013), which include information on respectful care of patients and their families after patient death. Watson (Watson Caring Science Institute, 2016) included a description of caring occasions and caring moments, heart-centered encounters with another person. She describes this concept when two people, each with their own background, come together in a human-to-human interaction that is meaningful, authentic, intentional, honoring, and sharing. Such an encounter allows each person to expand his or her worldview and spirit, leading to new discovery of self and others and new possibilities. The authors believe that, by implementing the bathing and honoring practice, a caring occasion is created between caregivers, family members, and their loved ones. Having the opportunity to make an environment that becomes a safe and healing place can later be seen as a significant or healing time in their lives. The practice is also aligned with recommendations by the AACN (1998), which include assisting families and colleagues to cope with “suffering, grief, loss, and bereavement in end-of-life care” (para. 16).

Although the literature supports continuing care after patient death, a need exists for evidence-based interventions that accomplish this type of care. The authors hope this article brings attention to the potential for research in this field. The bathing and honoring practice provides one intervention that may assist families, nurses, and other healthcare providers coping with grief and loss.

Conclusion

This is the first comprehensive summary of families’ experience with a bathing and honoring practice for their loved ones after death in an acute care setting. Families expressed universal support of the experience, with every participant stating that the practice was a profoundly positive, meaningful experience and that it supported them in their grieving. A bathing and honoring practice provides bedside nurses with an opportunity to make a long-lasting impact on family members’ experience of a loved one’s death and of the care received during their final days in the hospital. This study is a first step toward establishing specific nursing interventions as evidence-based practice that can be incorporated in routine nursing care for patients and families at the end of life.

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (1998). Peaceful death: Recommended competencies and curricular guidelines for end-of-life nursing care. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1RFzJyi

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2016). End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC). Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec

Beckstrand, R.L., Collette, J., Callister, L., & Luthy, K.E. (2012). Oncology nurses’ obstacles and supportive behaviors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 398–406.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, B., & Neville, A. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 545–547.

Cooney, A. (2011). Rigour and grounded theory. Nurse Researcher, 18, 17–22.

Dahlin, C. (Ed.). (2013). National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (3rd ed.). Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1URtEW1

Guion, L.A., Diehl, D.C., & McDonald, D. (2002). Triangulation: Establishing validity of qualitative studies (FCS6014). Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1PAU7zk

Koch, T. (2006). Establishing rigor in qualitative research: The decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 53, 91–103.

Moules, N., Simonson, K., Fleiszer, A., Prins, M., & Glasgow, B. (2007). The soul of sorrow work: Grief and therapeutic interventions with families. Journal of Family Nursing, 13, 117–141.

Moules, N., Simonson, K., Prins, M., Angus, P., & Bell, J. (2004). Making room for grief: Walking backwards and living forward. Nursing Inquiry, 11, 99–107.

Moules, N.J. (2002). Hermeneutic inquiry: Paying heed to history and Hermes, an ancestral, substantive, and methodological tale. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(3), 1–21.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2013). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Palliative care [v.1.2016]. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1RKzF6R

Olauson, J., & Ferrell, B. (2013). Care of the body after death: Nurses’ perspectives of the meaning of post-death patient care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 647–651.

Pattison, N. (2008a). Care of patients who have died. Nursing Standard, 22(28), 42–48.

Pattison, N. (2008b). Caring for patients after death. Nursing Standard, 22(51), 48–56.

Pitorak, E.F. (2003). Care at the time of death. American Journal of Nursing, 103(7), 42–53.

Polit, D.F., & Beck, C.T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Rando, T.A. (1985). Creating therapeutic rituals in the psychotherapy of the bereaved. Psychotherapy, 22, 236–240.

Running, A., Tolle, L.W., & Girard, D. (2008). Ritual: The final expression of care. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 14, 303–307.

Thirsk, L.M., & Moules, N.J. (2013). “I can just be me”: Advanced practice nursing with families experiencing grief. Journal of Family Nursing, 19, 74–98.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). Health, United States, 2010: With special feature on death and dying. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf

Watson Caring Science Institute. (2016). Caring science theory, research, and measurement. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1PAUcTx

Worden, J.W. (2009). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

About the Author(s)

Rodgers and Calmes are clinical nurses in the Inpatient Adult Oncology Unit and Grotts is a statistician in the Department of Research Compliance, all at the Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital in California. No financial relationships to disclose. Rodgers, Calmes, and Grotts contributed to the conceptualization and design. Rodgers and Calmes completed the data collection. Grotts provided the statistical support. Rodgers, Calmes, and Grotts contributed to the analysis and manuscript preparation. Rodgers and Calmes can be reached at dlrodgers27@gmail.com and bcalmes@sbch.org, respectively, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted February 2015. Accepted for publication November 26, 2015.