Repetitive Negative Thinking: The Link Between Caregiver Burden and Depressive Symptoms

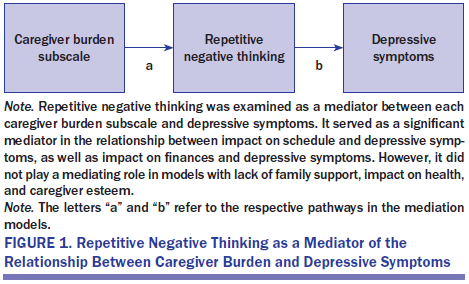

Purpose/Objectives: To explore whether repetitive negative thinking (RNT) mediates the pathway between subscales of caregiver burden and depressive symptoms.

Design: Cross-sectional pilot study.

Setting: Bone marrow unit at the University of Louisville Hospital in Kentucky and caregiver support organizations in Louisville.

Sample: 49 current cancer caregivers who were primarily spouses or partners of individuals with lymphoma or leukemia and provided care for a median of 30 hours each week for 12 months.

Methods: Caregivers completed questionnaires assessing caregiver burden, RNT, and depressive symptoms.

Main Research Variables: Caregiver burden, RNT, and depressive symptoms.

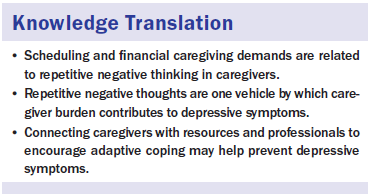

Findings: Results showed that RNT mediated the relationship between burden (as a result of impact on schedule or finances) and depressive symptoms. Although burden from a lack of family support and impact on health was positively related to depressive symptoms, these relationships were not mediated by RNT. In addition, caregiver esteem was not associated with RNT or depressive symptoms.

Conclusions: RNT plays an important role in maintaining and potentially exacerbating caregiver distress. Assessment and intervention regarding RNT in cancer caregivers may reduce depressive symptoms prompted by burden from an impact on schedule or finances.

Implications for Nursing: Nurses may be significant in connecting caregivers experiencing RNT to resources and professionals to enhance adaptive coping and potentially prevent depressive symptoms.

Jump to a section

The rate of depression in informal caregivers of individuals with cancer ranges from 10%–53% (Girgis, Lambert, Johnson, Waller, & Currow, 2013). In cancer caregivers, depression has been associated with poorer health, as well as lower levels of quality of life and life satisfaction; it may also affect caregivers’ ability to provide care (Swore Fletcher, Dodd, Schumacher, & Miaskowski, 2008). Examination of factors associated with depressive symptoms is important for the well-being of the caregiver and the care recipient.

Cancer caregiving is taxing, and, at times, it can become burdensome. Demands associated with caregiving have been shown to affect caregivers’ schedule, esteem, family support, health, and finances (Goren, Gilloteau, Lees, & DaCosta DiBonaventura, 2014; Park et al., 2012; Stenberg, Cvancarova, Ekstedt, Olsson, & Ruland, 2014; Tang et al., 2013). Impact in these respective areas results in symptoms such as being easily bothered, as well as experiencing fearfulness, isolation, and loneliness (Given et al., 2004). In addition, caregiver burden and low caregiver esteem has been linked with depressive symptoms (Lambert, Girgis, Lecathelinais, & Stacey, 2012; Stenberg et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2013). For example, a prior study of cancer caregivers found that burden, because of interference with daily activities, was associated with greater odds of developing borderline or clinically significant depression after 6 months and 12 months, respectively (Lambert et al., 2012). Similarly, greater impact on schedule and health, less family support, and lower caregiver esteem were associated with more depressive symptoms in a sample of 193 cancer caregivers (Tang et al., 2013). Overall, the literature supports a link between caregiver burden and depressive symptoms.

Theoretical models have posited that caregiver burden influences depressive symptoms through coping styles (Fletcher, Miaskowski, Given, & Schumacher, 2012; Knight & Sayegh, 2009). Fletcher et al. (2012) have described a model specific to the cancer context, in which appraisals of stressors in the cancer caregiving experience are associated with health and well-being through cognitive-behavioral responses (Fletcher et al., 2012). One key cognitive-behavioral coping mechanism that may play a role in the relationship between caregiver burden and depressive symptoms is repetitive negative thinking (RNT). RNT is a maladaptive thought process that requires mental capacity and is characterized by repetition, intrusiveness, and unproductiveness (Ehring et al., 2011). In addition, RNT is considered to be a transdiagnostic process, in that it spans multiple mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Ehring et al., 2011) and includes other forms of thinking, such as rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) and worry (Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990). Research has shown that RNT is a thought process that increases vulnerability for symptoms of depression and anxiety in individuals (Ehring et al., 2011; McEvoy & Brans, 2013), with experimental data demonstrating that RNT is a precursor to changes in mood (McLaughlin, Borkovec, & Sibrava, 2007).

Notably, some data show a link between caregiver burden and maladaptive coping styles (Papastavrou, Charalambous, & Tsangari, 2012). For example, caregivers who experienced high burden from the caregiving process endorsed greater use of avoidance and wishful thinking to cope, compared to more adaptive coping styles (Papastavrou et al., 2012). In addition, RNT has been positively associated with maladaptive cognitive efforts to control (e.g., worry) and avoid (e.g., suppress) unwanted and threatening thoughts (McEvoy, Moulds, & Mahoney, 2013). However, data examining RNT in cancer caregivers are lacking.

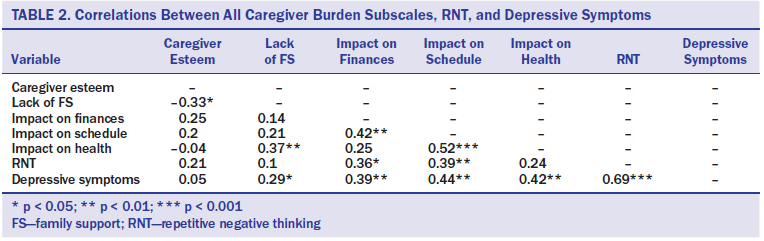

The current study examined associations among caregiver burden, RNT, and depressive symptoms in a sample of 49 cancer caregivers. Based on theory (Knight & Sayegh, 2009) and research (Papastavrou et al., 2012), burden experienced as a result of impact on schedule, health, and finances, as well as lack of family support, was thought to be positively associated with RNT; caregiver esteem was expected to be negatively associated with RNT. Also hypothesized was that RNT would be positively associated with depressive symptoms. Finally, RNT was expected to mediate the relationship between subscales of caregiver burden and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Fifty-seven participants were recruited for this study. Recruitment efforts consisted of in-person requests at the bone marrow unit of a local hospital (n = 36), email invitations to members of a caregiver support group at a local cancer center (n = 7) and a local cancer support organization (n = 11), and Listserv announcements to a university community (n = 3). No exclusion criteria for participation in the study existed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; surveys were completed using an online program or on paper. The study was approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board. Sample size was determined based on large effect sizes found in data examining associations between RNT and depressive symptoms (Ehring et al., 2011). Analyses focused on current caregivers who provided data on burden, RNT, and depressive symptoms. Seven participants were excluded (five participants did not identify as current caregivers, and two lacked data on the variables of interest, and one outlier was removed from analyses; this resulted in a sample of 49 caregivers).

Instruments

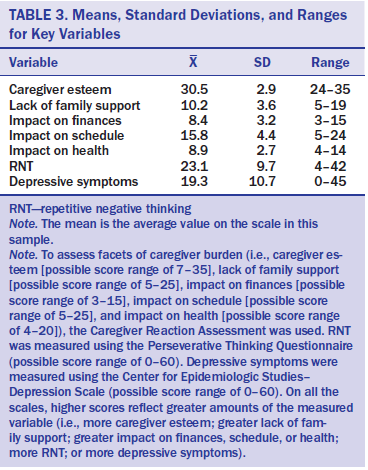

Caregiver Reaction Assessment: This 24-item tool was used to evaluate caregiver burden in participants (Given et al., 1992). Items were summed to calculate burden scores in five domains: caregiver esteem, lack of family support, impact on finances, impact on schedule, and impact on health (Given et al., 1992). Cronbach alphas for the burden scale in each domain have ranged from 0.62–0.83 in cancer caregiving samples (Nijboer, Triemstra, Tempelaar, Sanderman, & van den Bos, 1999), which was consistent in the current sample (0.69–0.78).

Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire: This 15-item tool was used to assess the degree to which participants engage in RNT (Ehring et al., 2011). The total sum score has been shown to exhibit good psychometric properties in adults (Cronbach alpha of 0.94–0.95) (Ehring et al., 2011). The overall internal consistency for the total sum score in the current study was 0.94.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale: This tool was used to assess depressive symptomatology in participants during the past week (Radloff, 1977). Prior research has shown a Cronbach alpha value of 0.9 in a caregiving sample (Carter & Chang, 2000). The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.9.

Data Analysis

One outlier, as defined by plus or minus three standard deviations (SDs) from the mean, was removed. Person mean substitution was used for missing data at the item level, which is appropriate given the limited data missing (Hawthorne & Elliott, 2005). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all participants. To test the proposed mediation models, the widely used approach posited by Preacher and Hayes (2008) was employed. This particular approach focuses on indirect effects because, in cases characterized by a competitive mediation (i.e., the indirect effect has significant opposing signs), a direct effect may not be significant when a mediation is present (Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010). Regression analyses were conducted to examine paths “a” and “b” in each mediation model (see Figure 1). Given the sample size, the competitive and complementary indirect effects (a*b) of the mediation models were examined using the RMediation program, as suggested by the literature (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). The RMediation program provides 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mediated effect using the distribution of product, Monte Carlo simulations, and an asymptotic normal distribution; a mediation is considered significant if it does not include zero (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011).

Results

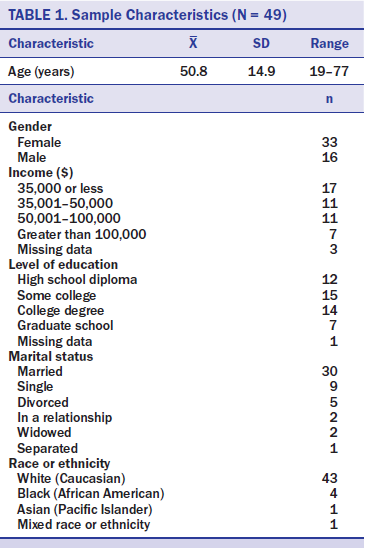

Demographic details of participants (49 current caregivers of individuals with cancer) are described in Table 1. In this sample, caregivers identified as a spouse or partner (n = 25), child (n = 6), parent (n = 7), sibling (n = 3), friend (n = 2), or other (n = 5) regarding their relationship with the care recipient (missing data = 1). Participants reported the cancer type of the care recipient as lymphoma or leukemia (n = 20), brain (n = 5), breast (n = 5), colorectal (n = 2), lung (n = 4), or other (e.g., bladder, skin, myeloma; n = 12) (missing data = 1). Caregivers provided care for as many as 264 months, with a median of 12 months, and the number of hours of care per week ranged from less than one hour to greater than 168 hours, with a median of 30 hours per week.

Correlations and means, along with SDs, are depicted in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Regression results are reported in Table 4. As expected, impact on schedule (p = 0.01) and finances (p = 0.006) were positively associated with RNT. However, caregiver esteem (p = 0.15), lack of family support (p = 0.48), and impact on health (p = 0.1) were not related to RNT. RNT was positively associated with depressive symptoms after controlling for each respective caregiver burden subscale (p < 0.001). Consistent with hypotheses, examination of the 95% CIs showed that RNT served as a mediator in the relationship between impact on schedule and depressive symptoms (95% CI [0.18, 1.06]), as well as in the relationship between impact on finances and depressive symptoms (95% CI [0.2, 1.62]). Contrary to expectations, RNT did not significantly mediate the relationships between caregiver esteem and depressive symptoms (95% CI [–0.18, 1.34]), lack of family support and depressive symptoms (95% CI [–0.36, 0.8]), or impact on health and depressive symptoms (95% CI [–0.09, 1.34]).

Discussion

The current study examined whether RNT mediated the relationship between subscales of caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in cancer caregivers. Results showed that burden resulting from impact on schedule and finances was associated with higher RNT. In addition, more RNT was positively related to depressive symptoms. As expected, burden from impact on schedule and finances was indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through RNT.

RNT plays an important role in the experience of cancer caregivers. A growing body of literature has examined coping styles used by cancer caregivers (Epiphaniou et al., 2012; Gaugler, Eppinger, King, Sandberg, & Regine, 2013; Lambert et al., 2012; Papastavrou et al., 2012). The current data are consistent with prior data showing that highly burdened caregivers are more likely to use wishful thinking or avoidance to cope, compared to assertiveness or positive approaches (Papastavrou et al., 2012). In addition, RNT and depressive symptoms have been linked in adults (Ehring et al., 2011) and dementia caregivers (Segerstrom, Schipper, & Greenberg, 2008). The current study extends these findings, showing that negative thoughts characterized by repetition, intrusiveness, and unproductiveness play a mediating role in the relationship between burden and depressive symptoms in cancer caregivers.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"30476","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"536","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"502"}}]]

Contrary to expectations, burden as a result of lack of family support and impact on health was not associated with RNT. In addition, caregiver esteem was not related to RNT. The reason for this remains unclear. Given the direct link between an absence of family support and impact on one’s health with depressive symptoms, the lack of findings regarding these subscales of burden were not because of nonapplicability. However, although burden because of impact on schedule and finances affects daily activities and immediate planning, impact on health, lack of family support, and caregiver esteem relate to long-term consequences. Perhaps these experiences of burden are associated with coping processes that relate to delayed outcomes.

The role of RNT in caregivers of patients with cancer is of clinical relevance. Specifically, the current findings provide information on how caregiver distress may be maintained and potentially exacerbated during the caregiving process. In other words, repetitive, intrusive, and unproductive cognitive focus on the impact of caregiving responsibilities on one’s schedule and finances is a maladaptive coping process by which distress may manifest as depressive symptoms. Based on such results, targeting RNT may be fruitful in interrupting and reducing depressive symptoms in cancer caregivers. For example, research has shown that mindfulness skills are helpful in reducing the degree to which people engage in RNT (Heeren & Philippot, 2011). Examination of the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions, including those led by nurses, in reducing RNT in cancer caregivers is needed.

The mediating role of RNT in the relationship between burden, due to impact on schedule or finances, and depressive symptoms supports relationships posited in the updated sociocultural stress and coping model (Knight & Sayegh, 2009) and the model developed by Fletcher et al. (2012). Both models hypothesize that coping mechanisms, including cognitive-behavioral responses such as RNT, would mediate the associations between appraisal of stressors (e.g., caregiver burden) and mental as well as physical health outcomes. Multilevel analyses examining the interplay of relationships in the complete models would be fruitful. In addition, although the mediations in the current study bring greater understanding of the relationships explored, they were cross-sectional in nature. Consequently, data examining these relationships across three timepoints are warranted.

In the current study, caregivers largely identified as White and female. Some data suggest that differences exist in caregiver burden and distress depending on gender and racial or ethnic identity (Girgis et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2012). Studies with larger cohorts should replicate these findings and examine potential moderating effects of sociodemographic characteristics. In addition, caregivers were primarily caring for someone with lymphoma or leukemia for a median of 30 hours a week for one year. The experience of burden because of demands associated with caregiving has been found across a multitude of cancers (Hartnett, Thom, & Kline, 2016). In addition, the stress process described in the theoretical model developed by Fletcher et al. (2012) has been posited to apply across the cancer trajectory. However, this model may operate differently by cancer type, stage, or treatment.

The current study did not examine outcomes beyond depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms have a prevalence rate of 10%–53% in cancer caregivers (Girgis et al., 2013) and are, therefore, an important outcome of clinical interest. However, theoretical models also describe potential pathways, including coping mechanisms, from caregiver burden to physical health outcomes (Fletcher et al., 2012; Knight & Sayegh, 2009). Some data have shown that rumination, one of the thought processes embedded in RNT, is associated with elevated biomarkers, such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein (Segerstrom et al., 2008; Zoccola, Figueroa, Rabideau, Woody, & Benencia, 2014). As a result, examination of physical and mental health outcomes are warranted in future studies.

Implications for Nursing

The current findings have clinical implications for the field of nursing. Nurses are often a primary source of caregiver interaction. As such, they are likely the recipient of discussion topics related to caregiving, such as financial and scheduling concerns, or the witness of RNT in caregivers. Data from the current study suggest that early detection and intervention regarding caregiver burden and RNT may be helpful in preventing the onset or reduction of existing depressive symptoms. The interactions between nurses and caregivers may be particularly important for connecting caregivers with support mechanisms (e.g., support groups, online resources, education materials), as well as behavioral health professionals (e.g., psychologists, social workers) when appropriate. Increased training opportunities or information for nurses about communication styles and behaviors in caregivers that indicate burden or RNT would be helpful in achieving a goal of early detection or intervention of caregiver depressive symptoms.

Nursing-guided interventions with caregivers are receiving increasing attention in the literature (Belgacem et al., 2013). In the current study, caregivers indicated that their schedule was negatively affected by their caregiving responsibilities. Consequently, brief interventions are important. Given that nurses likely interact with most caregivers (e.g., healthcare visits for care recipient), these may be opportune moments for the implementation of brief, empirically supported interventions. Continued examination of the effectiveness of brief nursing-led interventions, including those focused on reducing caregiver burden and RNT, is needed.

Conclusion

The current study showed that RNT mediates the relationship between burden, as a result of impact on schedule and finances, and depressive symptoms in a sample of 49 cancer caregivers. Findings highlight the important role that coping plays in the experience of caregiver distress. Future research examining caregiver distress or burden, coping, and mental and physical health outcomes within the context of cancer caregiver interventions is warranted.

About the Author(s)

Mitchell is a postdoctoral researcher at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus and was, at the time of this writing, a PhD candidate in the Department of Counseling and Human Development at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, and Pössel is a professor in the Department of Counseling and Human Development at the University of Louisville. No financial relationships to disclose. Mitchell completed the data collection and provided the analysis. Pössel provided statistical support. Both of the authors contributed to the conceptualization and design and manuscript preparation. Mitchell can be reached at amanda.mitchell2@osumc.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted May 2016. Accepted for publication July 20, 2016.