Factors Influencing Nurses’ Use of Hazardous Drug Safe Handling Precautions

Problem Identification: Nurses taking measures regarding the safe handling of hazardous drugs (HDs) can reduce their risk of exposure and environmental contamination. However, the findings of studies examining factors influencing the use of HD safe handling precautions by nurses have been inconsistent.

Literature Search: An integrative review of the Embase® and Scopus® electronic databases was performed.

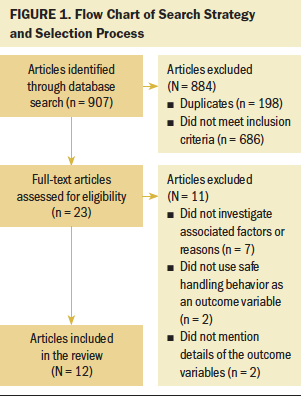

Data Evaluation: The search strategy yielded 907 articles. Ten quantitative studies and two qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria. The Health Evidence Bulletin Wales checklist was used to evaluate the quality of the articles.

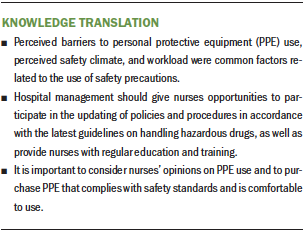

Synthesis: The outcome variables were categorized as engineering controls, work practice controls, and personal protective equipment (PPE) use. The frequency of PPE use was measured as an outcome variable in all reviewed studies. Associated factors were based on the behavioral-diagnostic model. Perceived barriers to PPE use, perceived safety climate, and workload were common factors related to the use of safety precautions.

Implications for Practice: Nurses should proactively obtain information about the safe handling of HDs and share their perceptions and experiences of it with their colleagues. Managers should actively construct a safe environment by adopting high reliability principles and provide nurses with sufficient and easy-to-use PPE.

Jump to a section

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health ([NIOSH], 2004) defines hazardous drugs (HDs) as inherently toxic drugs posing a risk to healthcare providers. They are characterized as having carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, reproductive toxicity, genotoxicity, and organ toxicity at low doses. Nurses comprise the largest proportion of healthcare providers who make contact with HDs during multiple types of clinical activities (Connor & McDiarmid, 2006). Because acceptable doses of occupational exposure to HDs have not yet been determined, current recommendations suggest that nurses take measures for the safe handling of HDs to reduce exposure to risk and environmental contamination as much as possible (Eisenberg, 2018).

The Oncology Nursing Society’s Chemotherapy and Biotherapy Guidelines and Recommendations for Practice (Polovich, Olsen, & LeFebvre, 2014) establishes protective measures for nurses exposed to HDs during clinical activities, with reference to guidelines by NIOSH (2004) and the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (2006). The measures outlined by Polovich et al. (2014) are based on a five-level, pyramid-shaped Hierarchy of Controls that can be followed by administrators and nurses. The top level of the pyramid involves reducing drug toxicity to control the risk from exposure, but this is generally not feasible in clinical practice. The remaining levels in the pyramid are similarly ranked, from most effective to least effective, according to how effective they are at controlling exposure: engineering controls, administrative controls, work practice controls, and personal protective equipment (PPE). Engineering controls reduce exposure through the use of equipment like biologic safety cabinets when preparing HDs and closed-system transfer devices when preparing and administering HDs. Administrative controls consist of policies and procedures for safe HD handling put in place by hospital management, regular updates to HD lists, education and training, medical surveillance, and exposure monitoring. Work practice controls consist of reducing risk exposure to environmental contamination, such as by washing hands, covering work surfaces with plastic-backed absorbent pads, and employing waste disposal methods for HDs. PPE refers to special gloves, nonabsorbent gowns, and respiratory and eye protection. Guidelines recommend the use of PPE during clinical activities where there is a risk of exposure to HDs (Polovich et al., 2014). Although there are clearly defined policies, nurse adherence to safety and protection measures is still not ideal. Boiano, Steege, and Sweeney (2014) found that nurses did not fully adhere to guidelines when performing exposure control measures during HD administration, including failure to wear a gown and chemotherapy gloves. He, Mendelsohn-Victor, McCullagh, and Friese (2017) determined that 90% of ambulatory nurses wore a single pair of gloves while administering and preparing HDs, even though the recommendation is for double gloving (NIOSH, 2004). Graeve et al. (2017) reported that double gloves were always used by about 34% of nurses when administering HDs.

Adherence by nurses to guidelines regarding the safe handling of HDs (Polovich et al., 2014) has been found in numerous studies to be inconsistent (Boiano et al., 2014; Graeve et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012). Additional investigation into the results of these studies is warranted, with a view toward providing a reference for future interventional studies and clinical work. The current authors used DeJoy’s (1986) behavioral-diagnostic model of workplace self-protective behavior to interpret factors associated with self-protective behaviors. The model is based on the PRECEDE (predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling causes in educational diagnosis and evaluation) model, which groups complex and multifaceted personal health behaviors into predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors (Green, Kreuter, Deeds, & Partridge, 1980). Predisposing factors refer to individual factors consisting of knowledge, perception of risk, beliefs and attitudes, perceptions of barriers, and the motivations individuals have for adopting behaviors. Reinforcing factors occur when individuals exercise behaviors and receive feedback, causing them to continue performing safety and protection measures. This behavioral feedback consists of approval from peers, supervisors, and managers. Reinforcing factors are organizational, and they take the form of specific policies and procedures, the safety climate, education, and training programs. Enabling factors are individual subjective perceptions of obstacles or encouragement to adopt behaviors, and they are environmental factors in the form of availability of resources, equipment, supplies, and workload. In the current integrative review, the authors used a multilevel analysis to confirm the factors associated with HD safe handling precautions to provide a reference for interventional studies and clinical practice.

Methods

Search Strategy

For this study, an integrative review method incorporating diverse methodologies was used (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Full-text searches of articles in the Embase® and Scopus® electronic databases were performed in October 2017 with the following Boolean search terms: (“safe handl*” OR precaution OR protec*) AND nurs* AND (“hazard* drug” OR antineoplastic OR chemo* OR cytotoxic OR antitumor). Database searches were conducted in English and were restricted to articles published from 2007 to October 2017 because organizational policy, nurses’ attitudes, and the standards for safe handling of HDs have gradually changed over time.

Study Selection

Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (a) were original, peer-reviewed research, (b) included nurses among the participants, (c) reported factors or reasons associated with the use of HD safe handling precautions by nurses, and (d) described the details of the outcome variables. A total of 907 articles were retrieved and imported into EndNote®, version X8, and 709 remained after eliminating duplicate articles. A total of 686 articles were eliminated because their titles and abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 23 full-text articles were accessed. Eleven articles were then excluded from the review because two did not use safe handling behavior as an outcome variable, two did not mention the details of the outcome variables, and seven did not investigate associated factors or reasons. Consequently, 12 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review (see Figure 1). The screening process was conducted by the first author, and the process for determining whether the articles met the inclusion criteria was performed by all authors.

Data Evaluation

Ten of the articles reviewed were quantitative studies, and two were qualitative studies. The Health Evidence Bulletin Wales checklist (Weightman, Mann, Sander, & Turley, 2004) was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. The articles were then organized into a data extraction sheet listing the study design, study location for recruiting participants, sample size, response rate, outcome variables, inferential statistics, and results. The first and second authors independently scored 4 of the 12 articles for quality and collectively arrived at a final quality score. The rest of the articles were then scored for quality by the first author.

Data Analysis

The parts of the studies related to HD safe handling precautions used by nurses were categorized according to the Hierarchy of Controls. The administrative controls in this hierarchy refer to the ways in which medical institution administrators focus on guidelines for safe HD handling, not how individual nurse behaviors adhere to the guidelines; this is why the current authors categorized the data according to engineering controls, work practice controls, and PPE. The associated factors were based on the behavioral-diagnostic model for factors associated with self-protective behaviors at work.

Results

Study Design and Measurement Tools

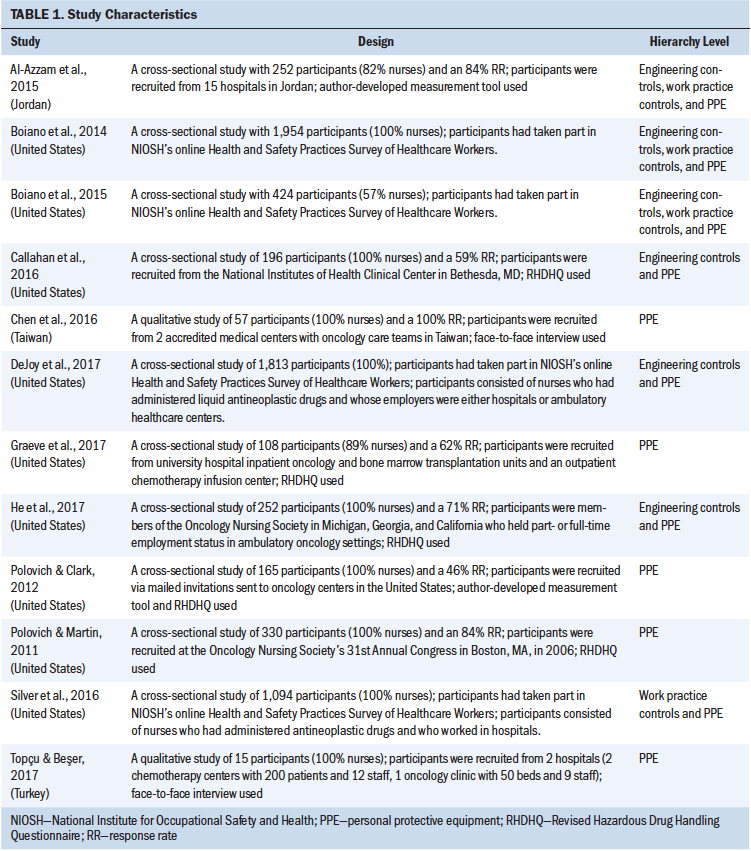

Nine of the 12 articles reviewed took place in the United States. In 10 studies, participants were recruited by multiple medical institutions or professional associations. Sample size estimation was reported only in the study by Polovich and Clark (2012), and only the two qualitative studies provided their inclusion criteria (Chen, Lu, & Lee, 2016; Topçu & Beşer, 2017). Nine of the studies consisted of only nurse participants (Boiano et al., 2014; Callahan et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; DeJoy et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012; Polovich & Martin, 2011; Silver, Steege, & Boiano, 2016; Topçu & Beşer, 2017), and three studies also included pharmacists in addition to nurses (Al-Azzam, Awawdeh, Alzoubi, Khader, & Alkafajei, 2015; Boiano, Steege, & Sweeney, 2015; Graeve et al., 2017). The number of study participants ranged from 15 to 1,954, and five studies had a participation rate higher than 60% (Al-Azzam et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Graeve et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Martin, 2011) (see Table 1).

The Revised HD Handling Questionnaire (RHDHQ) (Polovich & Clark, 2012) was used in several studies and was based on the 20-item Chemotherapy Handling Questionnaire (Martin & Larson, 2003), which assesses the frequency of use of PPE during clinical activities that involve handling HDs (e.g., drug preparation, administration, disposal), among other variables, and measures this using a three-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (usually) to 3 (rarely). The RHDHQ measures frequency of use of PPE using a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). The internal consistency of the RHDHQ was measured, but its validity was not examined. Boiano et al. (2014, 2015), DeJoy et al. (2017), and Silver et al. (2016) used data regarding nurses’ use of HD safe handling precautions collected in a nationwide online survey developed and conducted in the United States in 2011 by NIOSH (Health and Safety Practices Survey of Healthcare Workers).

The frequency of PPE use was regarded as an outcome variable in all studies reviewed. Five of the 12 studies considered PPE use to be the only outcome variable, whereas the other seven articles also regarded work practice controls or engineering controls, or both, as outcome variables. In most of the studies, the means for the outcome variables were calculated, and factors associated with them were investigated using multiple regression. For example, Polovich and Clark (2012) calculated the mean for nurses’ frequency of use of chemotherapy gloves, double gloves, nonabsorbent gowns, eye protection, and respiratory protection during HD administration and waste handling, and Callahan et al. (2016) used the same method, although without specifying the exact scoring method for the outcome variables. Graeve et al. (2017) calculated the mean of nurses’ frequency of use of chemotherapy gloves, double gloves, nonabsorbent gowns, reusable isolation gowns, eye protection, and respiratory protection, but without describing specific clinical scenarios. He et al. (2017) also calculated the mean of nurses’ frequency of use of chemotherapy gloves, double gloves, nonabsorbent gowns, eye protection, respiratory protection, and closed-system transfer devices during drug preparation and administration.

However, DeJoy et al. (2017) and Silver et al. (2016) calculated the respective total scores for different control levels in the Hierarchy of Controls. In the DeJoy et al. (2017) study, engineering controls were measured using nurses’ scores concerning always using a closed-system transfer device, Luer lock fittings, and needleless systems. In Silver et al.’s (2016) study, the number of activities in which gloves contaminated with HDs came into contact with other work environments was defined as an outcome variable. Both studies calculated total scores of PPE adherence using the sum of four PPE actions (the frequency of always using chemotherapy gloves, double gloves, nonabsorbent gowns, and eye or face protection when administering liquid HDs). A chi-square test or correlation analysis was performed between each precaution item and various independent variables in two of the studies examined (Al-Azzam et al., 2015; Polovich & Martin, 2011).

Six of the 10 quantitative studies fulfilled the assessment criteria of the Health Evidence Bulletin Wales checklist (Al-Azzam et al., 2015; Callahan et al., 2016; Graeve et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012; Polovich & Martin, 2011). In the remaining four quantitative studies, the response rate was not reported; consequently, the criterion of whether confounding factors and bias were considered was not fulfilled. Among the two qualitative studies, Chen et al. (2016) fulfilled all the criteria in the checklist, whereas Topçu and Beşer (2017) failed to satisfy two criteria: whether the author’s position was stated clearly and whether the sampling strategy was described clearly and justified.

Factors Related to Nurses’ Use of Hazardous Drug Safe Handling Precautions

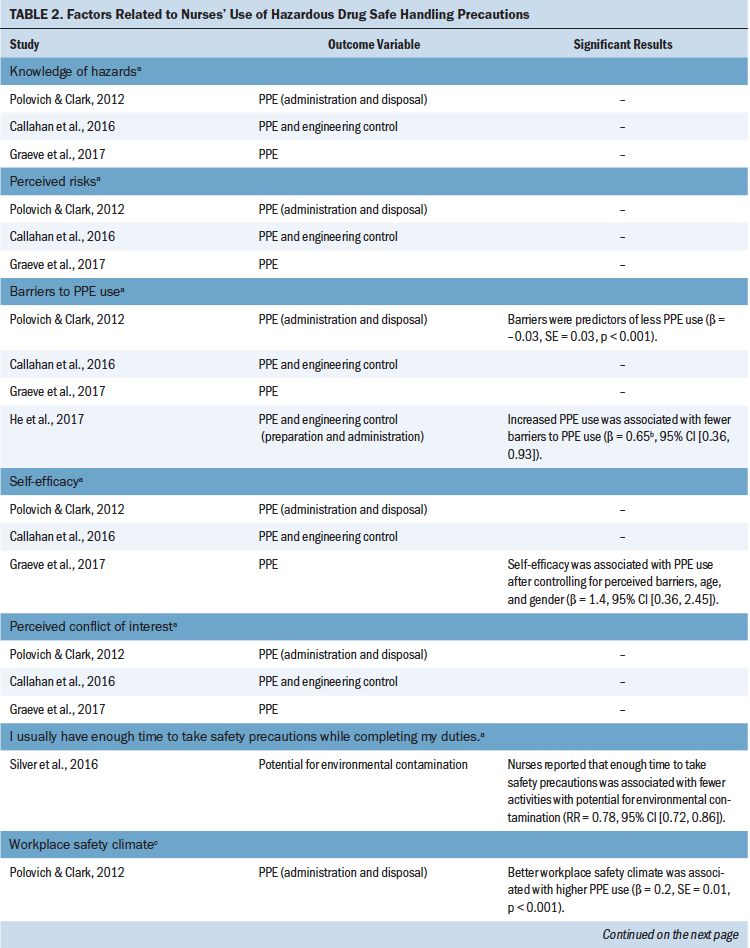

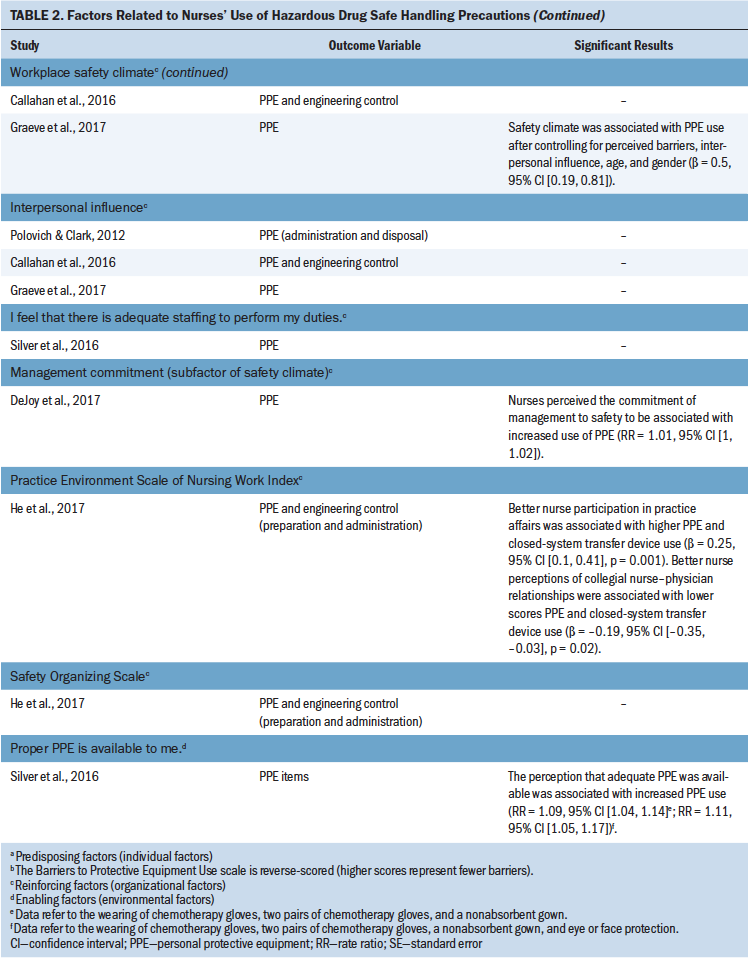

Individual factors: Three studies indicated that factors such as nurses’ knowledge about HD exposure, perceived risk of harm from HD exposure, and perceived conflict of interest were not significantly associated with the outcome variables (Callahan et al., 2016; Graeve et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012). Graeve et al. (2017) found that self-efficacy of PPE use was positively associated with frequency of PPE use. Polovich and Clark (2012) and He et al. (2017) found that nurses perceiving fewer barriers to PPE use would employ PPE more frequently when handling HDs. Silver et al. (2016) reported that the more the nurses agreed that they had adequate time to adopt safety precautions, the less frequently they wore gloves previously contaminated with HDs in other work environments (see Table 2).

The 2011 Health and Safety Practices Survey of Healthcare Workers conducted by NIOSH found that the main reasons for not using PPE were the minimal possibility of skin exposure, exclusion of PPE from the protocol, lack of equipment provided by employers, and the presence of engineering controls for protection (Boiano et al., 2014, 2015).

Organizational factors: Polovich and Clark (2012) used the 20-item Hospital Safety Climate Scale proposed by Gershon et al. (1995) with modifications to the items pertinent to HD handling, and they found that a better workplace safety climate was associated with a higher frequency of PPE use. Subsequently, Callahan et al. (2016) and Graeve et al. (2017) conducted studies based on the Workplace Safety Climate questionnaire developed by Polovich and Clark (2012). Callahan et al. (2016) reported no significant association between workplace safety climate and frequency of PPE use, whereas Graeve et al. (2017) reported that the safety climate was positively associated with the frequency of PPE use when the multivariate regression models did not include the unit where the participants worked.

DeJoy et al. (2017) used an exploratory factor analysis to yield three factors for the safe perception questions that asked participants about safety where they work: management commitment to safety, risk perception, and safety voice. This study indicated that management commitment was associated with a higher frequency of use of engineering controls and PPE (DeJoy et al., 2017).

He et al. (2017) reported that higher scores on the nurse participation in practice affairs subscale of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) (Lake & Friese, 2006) were associated with a higher frequency of PPE use. However, they also observed a significant negative correlation between the scores on the collegial nurse–physician relationships subscale of the PES-NWI and the frequency of PPE use.

The studies by Callahan et al. (2016), Graeve et al. (2017), and Polovich and Clark (2012) show that interpersonal influence in the workplace, as perceived by participants, was not significantly associated with the frequency of PPE use.

Environmental factors: The study by Silver et al. (2016) indicated that higher nurse-perceived availability of PPE was associated with increased PPE use.

Personal factors: Regarding work experience, years of experience in handling HDs and frequency of PPE use have been shown to be negatively correlated with each other. For example, studies by DeJoy et al. (2017) and Silver et al. (2016) reported that nurses with more experience administering HDs used PPE less frequently. Silver et al. (2016) also found that nurses with more work experience were involved in more activities where cross-contamination might occur.

Nurses who had received education and training in the safe handling of HDs used safety precautions more frequently than those who had not received such education and training. Al-Azzam et al. (2015) indicated that participants who had received on-the-job education about chemotherapy used safe handling precautions more frequently than those who had not. The study by Silver et al. (2016) revealed that nurses who had received training within the past year were more likely to use PPE frequently. DeJoy et al. (2017) also found that nurses who were trained in safe handling of HDs displayed a higher frequency of use of engineering control measures. Silver et al. (2016) and DeJoy et al. (2017) reported that nurses who were more familiar with guidelines for HD safe handling used more PPE.

Factors related to the background of the nurses’ workplace: The organizational characteristics of nurses’ workplaces were also associated with the use of PPE by nurses. Polovich and Martin (2011) found that nurses in a private practice setting used double gloves less frequently during drug preparation and administration. DeJoy et al. (2017) indicated that nurses at government or nonprofit organizations used PPE and engineering controls more frequently. He et al. (2017) reported that PPE was used more frequently by nurses in non-private medical institutions. Nurses in outpatient departments used PPE less frequently compared to those in inpatient units (DeJoy et al., 2017; Polovich & Martin, 2011). Graeve et al. (2017) found that nurses in bone marrow transplantation units used PPE more frequently than those in oncology and outpatient departments.

Nurses provided with established policies or procedures for safe HD handling in their workplaces adopted PPE more frequently. Polovich and Martin (2011) indicated that nurses whose organizations had updated their policies for the safe handling of chemotherapy drugs in accordance with the 2004 NIOSH Alert used double gloves more frequently. Silver et al. (2016) and DeJoy et al. (2017) reported that nurses whose organizations provided procedures for the safe handling of HDs used more PPE and engineering controls. DeJoy et al. (2017) also reported that nurses at institutions that provided HD spill kits and had implemented measures like monitoring environmental exposure and employees’ health used more PPE items.

DeJoy et al. (2017) and Silver et al. (2016) also indicated that nurses who had administered more HDs in the previous week used PPE less frequently. Callahan et al. (2016), He et al. (2017), and Polovich and Clark (2012) reported that PPE use decreased as the number of patients cared for by nurses increased.

Qualitative Studies

The ethnographic qualitative study by Chen et al. (2016) found that nurses appeared to emphasize work efficiency and their professional image when citing reasons for not using PPE. Experienced nurses felt confident in their ability to avoid exposure to chemotherapy toxicity.

Topçu and Beşer (2017) employed the Health Belief Model to interview nurses on their perceptions of the use of HD safe handling precautions, finding that a heavy workload, an excessively low nurse-to-patient ratio, and a lack of PPE and safety knowledge were barriers to PPE use. Providing education, safety reminders, and an established safety culture can be cues for action to improve PPE use.

Discussion

In the current integrative literature review to confirm the factors associated with nurses’ use of safe handling precautions for HDs, the authors did not find consistent results across the studies, perhaps because of differences in measurement tools. Two crucial problem areas have been identified: factors related to the safety precautions used by nurses and to the measurement tools used in different studies.

Perceived barriers to PPE use, self-efficacy of PPE use, the safety climate, nurses’ participation in public affairs, nurse–physician cooperation, and perceived availability of PPE were significant factors associated with nurses’ safety behaviors. Nurses’ use of safety precautions was significantly associated with their work experience, participation in education on safety precautions, familiarity with safety guidelines, organizational characteristics (public or nonprofit hospital), work unit characteristics (outpatient or inpatient department), safe handling policies and procedures in the workplace, and workload. The results of the current review are similar to those of Valim, Marziale, Richart-Martínez, and Sanjuan-Quiles (2014), who investigated factors related to healthcare providers’ adherence to infection control practices, identifying various important factors including employee training, perception of a safe environment, perceived barriers to adherence to standard precautions, and knowledge. Adherence to safe HD handling precautions may prevent healthcare workers’ exposure to HDs, subsequent health threats, and the contamination of work environments.

Qualitative and quantitative studies have indicated that nursing workload, perceived safety climate in the workplace, and perceived barriers to PPE use were the most common variables affecting the use of safety precautions by nurses. Consequently, it is likely that efforts could be made in relation to these variables that would increase the frequency of nurses’ use of safety precautions. Regarding nursing workload, managers can adjust the daily number of patients and the weekly amount of HDs handled by nurses. In terms of perceived safety climate in the workplace, managers could adopt relevant high reliability principles to create a safe work environment and enhance employees’ positive perception of the commitment to safety (e.g., deference to expertise), as well as provide nurses with opportunities to participate in policy decisions and in selecting suitable PPE for purchase. In addition, with respect to the principle of commitment to resilience, healthcare organizations must promote a learning environment by encouraging employees to share their perceptions of workplace safety; this could lead nurses to influence one another through peer interactions, therefore creating a safer work environment (Lin, Lin, & Lou, 2017; Oster & Deakins, 2018). In a prospective interventional study by Keat, Sooaid, Yun, and Sriraman (2013) that involved the preparation of HDs in readily used forms with labels containing clear handling instructions, providing education and training and renewing standard operating procedures led to enhanced knowledge, attitudes, and practices associated with the safe handling of HDs by nurses. In regard to perceived barriers to PPE use, Polovich and Clark (2012) and He et al. (2017) averaged participants’ responses to all tool items and examined the results through a regression analysis. Polovich and Clark (2012) and He et al. (2017) found that although the perceived barriers to PPE use were significantly associated with the outcome variables, it was not clear which subscales were associated with the frequency of PPE use; this made designing measures to reduce participants’ perceptions of the barriers to PPE use difficult. Some of the studies reviewed (Boiano et al., 2014, 2015) showed that nurses’ reasons for not using PPE may be linked to their belief that their exposure to HDs was minimal and to their lack of knowledge regarding the protective function of PPE. Consequently, the current authors recommend that managers discuss with their employees clinical situations and activities in which exposure to HDs may have occurred, disseminate information regarding the protective function of PPE, and ensure that employees are able to recognize potential hazards at work.

In addition, managers should take steps to enact a comprehensive improvement plan that includes providing updated policies and procedures, offering education and training, ensuring employee participation in this education and training, procuring easy-to-use and comfortable PPE, and reducing workloads. These measures should enhance the perception of the organizational safety climate and reduce perceived barriers to PPE use.

The nature of the organization or work unit is a fixed variable. A conceptual analysis by Lin et al. (2017) indicated that the characteristics of healthcare organizations are among the antecedents for the safety climate, and Graeve et al. (2017) found that, after controlling variables related to the participants’ work units, the perceived safety climate was not associated with the frequency of PPE use. These findings suggest that the perceived safety climate may vary by organization and that interventions need to be tailored to individual workplaces based on an understanding of how nurses perceive the safety climate dimensions in their respective environments.

The current integrative review showed that nurses’ work experience and work environment affected how they used safety precautions. Confirmation of these unchangeable factors can provide a reference for the design of tailored interventions. Such factors can also be used as control variables in studies that test the efficacy of interventions.

The factors affecting PPE use that were reported in the two qualitative studies examined in this review (Chen et al., 2016; Topçu & Beşer, 2017) were not identified as significant correlates of PPE use in the quantitative studies. If different factors are related to the implementation of safe HD handling precautions by nurses according to regional or cultural backgrounds, the use of a qualitative method to investigate those factors and to construct a model is suggested, followed by the use of a quantitative method to measure the correlation between the variables in the model. Although cause-and-effect relationships cannot be validated cross-sectionally, understanding the correlation between variables can help with experimental research, which can validate the underlying cause-and-effect relationships between model variables.

Limitations

Four studies used measurement tools developed by other researchers without testing their construct validity (Callahan et al., 2016; Graeve et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012), which could possibly explain the inconsistent results across different studies. Polovich and Clark (2012) developed a model for the prediction of safe HD handling precautions from other fields and modified measurement tools to suit the context of HD handling. Although content validity was performed in such studies (Al-Azzam et al., 2015; Boiano et al., 2014, 2015; Polovich & Martin, 2011), construct validity should be tested to determine the degree to which a tool can accurately measure abstract concepts. In addition, employment background and cultural characteristics should be addressed in measurement tools to better reflect the perception of HD safe handling precautions.

PPE use is at the bottom of the Hierarchy of Controls because it is the least effective measure for controlling HD exposure and does not prevent environmental contamination. However, it is the last line of defense against the entry of HDs into the human body. Sugiura et al. (2011) found that HDs were not detected in the urine of employees using PPE, even though swab samples indicated HD contamination of the work environment. Nurses are personally responsible for using PPE for their own safety, making this an important indicator of individual adherence with safety guidelines. This is possibly why PPE use is seen as an outcome variable in all of the studies examined in the current review. However, work practice controls are deemed to be more effective than PPE in the prevention of HD exposure, according to the Hierarchy of Controls. Apart from protecting personal safety, such controls can also prevent environmental contamination. Silver et al. (2016) included work practice controls as an outcome variable. Engineering controls are mainly used in drug preparation and administration, and most of the studies on drug administration selected the frequency of closed-system transfer device use as an outcome variable. However, closed-system transfer device use is related to the procedures of dispensing departments and is not entirely controlled by personal will. This could possibly explain why most studies did not include the use of closed-system transfer devices as an outcome variable.

In four articles (Callahan et al., 2016; Graeve et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Polovich & Clark, 2012), scores for outcome variables were obtained by calculating the mean of the frequency of use of different precautions in different activities involving HD handling. However, clinical activities involving HD handling differ in terms of the level of risk of HD exposure and the necessary controls for nurses. By calculating the mean, a certain amount of information was discarded, and the correlation between independent and dependent variables in the model could not be measured precisely. Therefore, an analysis of outcome variables should be conducted separately based on the different clinical activities that involve HD handling. Future studies should include measures related to other levels in the Hierarchy of Controls and self-protection behaviors in the measurement tools for outcome variables. Individual scores should be calculated based on different clinical activities involving HD handling and different levels in the Hierarchy of Controls to determine the factors influencing the levels of precautions required by various clinical activities.

Most of the qualitative and quantitative studies reviewed enrolled participants from different organizations. The studies were of high quality, with findings that adequately determined the factors affecting nurses’ behavior. A publication bias may have occurred; the literature search performed for this review was restricted to published articles and certain publication languages. The inconsistent results across different studies may be attributable to a lack of standardization and construct validity in the measurement tools. Because the methods for self-reporting and scoring outcome variables differed across studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Future Research

Nurses should obtain information about the protective function of PPE proactively, recognize potential hazards in their work environment, and share their perceptions and experiences of the safe handling of HDs with their colleagues. In addition, managers could conduct a brief meeting at shift change to communicate potential safety issues to nurses and ensure the effective distribution of safety information. Hospital management must establish policies and procedures in accordance with the latest guidelines for handling HDs and provide employees with opportunities to participate in practice affairs (e.g., policy decision making) and regular education and training. It is important to know more about the perceived barriers to PPE use and to provide suitable improvement measures, such as finding optimal locations for PPE placement and purchasing PPE that adheres to safety standards and is comfortable to use. Attention should also be paid to nursing workloads, particularly for nurses who frequently handle HDs. Active efforts for building a safe work environment can enhance the positive perception of the safety climate, reinforcing the willingness of employees to use safety precautions.

Future studies should use questionnaires that contain items on safety precautions that are suited to the clinical context involving the frequent handling of HDs. Items should include precautions at other levels of the Hierarchy of Controls to gain a better understanding of the discrepancies between safety guidelines and the clinical use of safety precautions by nurses. A research framework with preset models validated through structural equation modeling would facilitate the precise identification of influencing factors while reducing information loss.

Conclusion

In this integrative review, the frequency of PPE use was measured as an outcome variable in all studies. Inconsistent results were found across the studies; possible reasons for this include the lack of a comprehensive psychometric analysis of the measurement tools used, use of different scoring methods for outcome variables, and differences in the work environments. Perceived barriers to PPE use, perceived safety climate, and workload were common factors related to the use of safety precautions. Recommendations include increasing the nurse-to-patient ratio, reducing workloads, actively constructing a safe work environment by applying high reliability principles, and providing nurses with sufficient and easy-to-use PPE.

About the Author(s)

Ying Siou Lin, RN, MSN, is a doctoral candidate in the School of Nursing in the College of Medicine at National Taiwan University and an RN in the Department of Nursing at the National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei; and Yu Chia Chang, RN, MSN, is a doctoral student, Yen-Chun Lin, RN, PhD, is an assistant professor, and Meei-Fang Lou, RN, PhD, is a professor, all in the School of Nursing in the College of Medicine at National Taiwan University. No financial relationships to disclose. Ying Siou Lin, Chang, and Lou contributed to the conceptualization and design. Ying Siou Lin, Yen-Chun Lin, and Lou contributed to the manuscript preparation. Ying Siou Lin and Lou completed the data collection and provided statistical support. All authors provided the analysis. Lou can be reached at mfalou@ntu.edu.tw, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2018. Accepted November 26, 2018.)

References

Al-Azzam, S.I., Awawdeh, B.T., Alzoubi, K.H., Khader, Y.S., & Alkafajei, A.M. (2015). Compliance with safe handling guidelines of antineoplastic drugs in Jordanian hospitals. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 21, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155213517128

American Society of Health System Pharmacists. (2006). ASHP guidelines on handling hazardous drugs. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 63, 1172–1191. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp050529

Boiano, J.M., Steege, A.L., & Sweeney, M.H. (2014). Adherence to safe handling guidelines by health care workers who administer antineoplastic drugs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 11, 728–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2014.916809

Boiano, J.M., Steege, A.L., & Sweeney, M.H. (2015). Adherence to precautionary guidelines for compounding antineoplastic drugs: A survey of nurses and pharmacy practitioners. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 12, 588–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2015.1029610

Callahan, A., Ames, N.J., Manning, M.L., Touchton-Leonard, K., Yang, L., & Wallen, R. (2016). Factors influencing nurses’ use of hazardous drug safe-handling precautions. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.43-03AP

Chen, H.C., Lu, Z.Y., & Lee, S.H. (2016). Nurses’ experiences in safe handling of chemotherapeutic agents: The Taiwan case. Cancer Nursing, 39(5), E29–E38.

Connor, T.H., & McDiarmid, M.A. (2006). Preventing occupational exposures to antineoplastic drugs in health care settings. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 56, 354–365.

DeJoy, D.M. (1986). A behavioral-diagnostic model for self-protective behavior in the workplace. Professional Safety, 31, 26–30.

DeJoy, D.M., Smith, T.D., Woldu, H., Dyal, M.A., Steege, A.L., & Boiano, J.M. (2017). Effects of organizational safety practices and perceived safety climate on PPE usage, engineering controls, and adverse events involving liquid antineoplastic drugs among nurses. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 14, 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2017.1285496

Eisenberg, S. (2018). USP <800> and strategies to promote hazardous drug safety. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 41, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000257

Gershon, R.R.M., Vlahov, D., Felknor, S.A., Vesley, D., Johnson, P.C., Delcios, G.L., & Murphy, L.R. (1995). Compliance with universal precautions among health care workers at three regional hospitals. American Journal of Infection Control, 23, 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/0196-6553(95)90067-5

Graeve, C.U., McGovern, P.M., Alexander, B., Church, T., Ryan, A., & Polovich, M. (2017). Occupational exposure to antineoplastic agents: An analysis of health care workers and their environments. Workplace Health and Safety, 65, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916662660

Green, L.W., Kreuter, M.W., Deeds, S.G., & Partridge, K.B. (1980). Health education planning: A diagnostic approach. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

He, B.Y., Mendelsohn-Victor, K., McCullagh, M.C., & Friese, C.R. (2017). Personal protective equipment use and hazardous drug spills among ambulatory oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.ONF.60-65

Keat, C.H., Sooaid, N.S., Yun, C.Y., & Sriraman, M. (2013). Improving safety-related knowledge, attitude and practices of nurses handling cytotoxic anticancer drug: Pharmacists’ experience in a general hospital, Malaysia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 14, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.69

Lake, E., & Friese, C.R. (2006). Variations in nursing practice environments: Relation to staffing and hospital characteristics. Nursing Research, 55, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200601000-00001

Lin, Y.-S., Lin, Y.-C., & Lou, M.-F. (2017). Concept analysis of safety climate in healthcare providers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 1737–1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13641

Martin, S., & Larson, E. (2003). Chemotherapy-handling practices of outpatient and office-based oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1188/03.ONF.575-581

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2004). NIOSH alert: Preventing occupational exposure to antineoplastic and other hazardous drugs in health care settings. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2004-165/pdfs/2004-165.pdf?id=10.26616/N…

Oster, C.A., & Deakins, S. (2018). Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 48, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

Polovich, M., & Clark, P.C. (2012). Factors influencing oncology nurses’ use of hazardous drug safe-handling precautions [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, E299–E309. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.ONF.E299-E309

Polovich, M., & Martin, S. (2011). Nurses’ use of hazardous drug-handling precautions and awareness of national safety guidelines. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.718-726

Polovich, M., Olsen, M., & LeFebvre, K.B. (Eds.). (2014). Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice (4th ed.). Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society.

Silver, S.R., Steege, A.L., & Boiano, J.M. (2016). Predictors of adherence to safe handling practices for antineoplastic drugs: A survey of hospital nurses. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 13, 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2015.1091963

Sugiura, S., Nakanishi, H., Asano, M., Hashida, T., Tanimura, M., Hama, T., & Nabeshima, T. (2011). Multicenter study for environmental and biological monitoring of occupational exposure to cyclophosphamide in Japan. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 17, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155210369851

Topçu, S., & Beşer, A. (2017). Oncology nurses’ perspectives on safe handling precautions: A qualitative study. Contemporary Nurse, 53, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2017.1315828

Valim, M.D., Marziale, M.H., Richart-Martínez, M., & Sanjuan-Quiles, Á. (2014). Instruments for evaluating compliance with infection control practices and factors that affect it: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 1502–1519. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12316

Weightman, A.L., Mann, M.K., Sander, L., & Turley, R.L. (2004). Health Evidence Bulletins Wales: A systematic approach to identifying the evidence. Project methodology 5. Cardiff, Wales: Information Services, University of Wales College of Medicine.

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x