Barriers and Facilitators to Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Somali Immigrant Women: An Integrative Review

Problem Identification: Somali immigrant women access breast and cervical cancer screenings at a significantly lower rate than other women in the United States and face unique barriers and facilitators to cancer screening.

Literature Search: A literature search was performed using CINAHL®, PubMed®, EBSCOhost, PsycINFO®, MEDLINE®, and Google ScholarTM. Articles included qualitative studies that explored the barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screening in Somali immigrant women.

Data Evaluation: 10 articles were summarized using a standardized data matrix. Evidence was integrated into a synthesis of evidence and organized by theme.

Synthesis: According to the literature reviewed, Somali immigrant women face knowledge, cultural, and healthcare system barriers to screening for breast and cervical cancer. Recommendations to increase screening included providing culturally tailored education, increasing community involvement, and improving provider education.

Implications for Research: Understanding the barriers and facilitators that are unique to Somali immigrant women can assist nurse researchers and practitioners in developing evidence-based interventions that will provide support to this underserved population.

Jump to a section

The American Cancer Society (ACS, 2020a) estimates that in 2020 there will be about 276,480 new female breast cancer diagnoses and 42,170 deaths from female breast cancer in the United States. In the 2010 National Health Interview Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2012) reported that 72% of U.S.-born women accessed breast cancer screening services, but only 47% of immigrant women who had lived in the United States for 10 years or fewer received recommended screening services. Research indicates that Somali immigrant women in particular have low rates of breast cancer screening. In a data analysis of refugee patients’ service uptake in a primary care setting in Minnesota, Morrison et al. (2012) found that only 15% of eligible Somali immigrant women received a mammogram compared to 48% of non-Somali immigrant women.

In addition, about 13,800 cases of cervical cancer will be diagnosed, and 4,290 deaths from cervical cancer are expected in 2020 (ACS, 2020b). According to ACS (2020b), cervical cancer deaths have decreased considerably following increased screening with Papanicolaou (Pap) testing. However, disparities in screening continue among ethnic minority and immigrant populations, particularly Somali refugees (Harcourt et al., 2013; Morrison et al., 2012). In a data analysis of cancer screening uptake in Minnesota, Harcourt et al. (2013) found that 55% of Somali immigrant women reported never receiving a Pap test, compared to 43% of other African immigrant women. The CDC (2012) reports that 85% of U.S.-born women have received a Pap test within the past three years, whereas only 67% of immigrant women who have lived in the United States for 10 years or fewer have received this recommended cervical cancer screening.

Humanitarian crises worldwide have led to an influx of nearly three million refugees to the United States since 1980 (Krogstad & Radford, 2017). The Pew Research Center indicates that the United States has admitted 104,100 Somali refugees since 2001 (Krogstad, 2019). According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2015), the Somali healthcare system and public health infrastructure ranks among the poorest in the world. In a survey of cancer screening capabilities, WHO (2014) reported that Pap testing, acetic acid visualization, and mammography were generally not available within the public healthcare system in Somalia, and there was no national immunization program for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. In Somalia, breast and cervical cancer also have the highest incidence and mortality rates of all cancers affecting women (WHO, 2014).

To promote improved health in this population, the U.S. healthcare system must adapt to meet the needs of Somali immigrant women. The purpose of this integrative review was to explore the beliefs, attitudes, and other factors that affect the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening in Somali immigrant women and to provide recommendations for future interventions to address this disparity in cancer screening.

Methods

Search Strategy

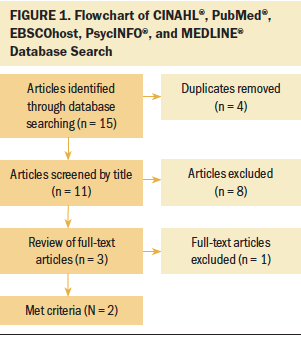

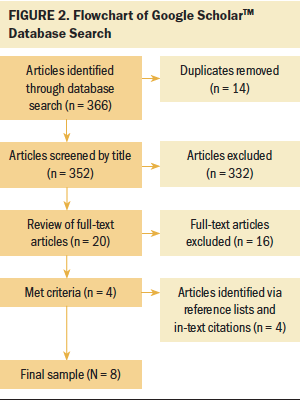

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework guided the search strategy for this review. An initial database search was performed using CINAHL®, PubMed®, EBSCOhost, PsycINFO®, and MEDLINE®. Search terms included Somali women, breast cancer, cervical cancer, barriers, and facilitators. A second search was performed using Google ScholarTM, with search terms including Somali women, breast cancer, cervical cancer, screening, barriers, facilitators, knowledge, and health beliefs.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies performed from 2007 to 2018 with an exclusive focus on Somali immigrant women’s beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes toward breast and/or cervical cancer screening (e.g., mammography, Pap testing) were included. In addition, studies were included if they sought to determine Somali women’s barriers and facilitators to cancer screening, as well as their attitudes toward preventive health care. To be included, studies involving other patient populations had to clearly identify Somali-specific beliefs. Studies that included data from other populations (e.g., East African immigrants), where data specific to Somali immigrant women could not be identified, were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they focused on HPV vaccinations, included men, solely addressed healthcare providers, only reported rates of cancer screening, or did not address breast or cervical cancer screening. For this review, studies originating from countries outside of the United States were included.

Search Outcome

The initial literature search produced 15 results. After eliminating duplicates, eight article titles and three full-text articles were screened. Two articles met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). The second search in Google Scholar yielded 366 articles. Fourteen duplicate articles were eliminated, and 332 articles were eliminated after screening article titles. Twenty full-text articles were screened, and four met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 2). Four additional articles were identified through reference lists and in-text citations that met the inclusion criteria. All articles were identified as qualitative research; no interventional or experimental research studies met the inclusion criteria.

Data Evaluation

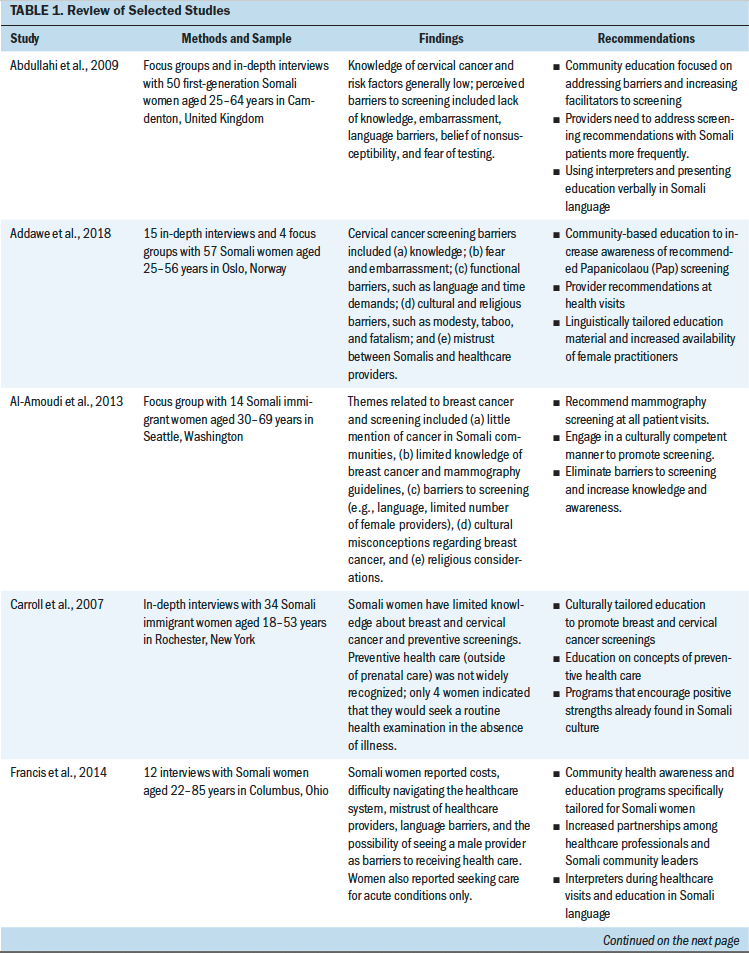

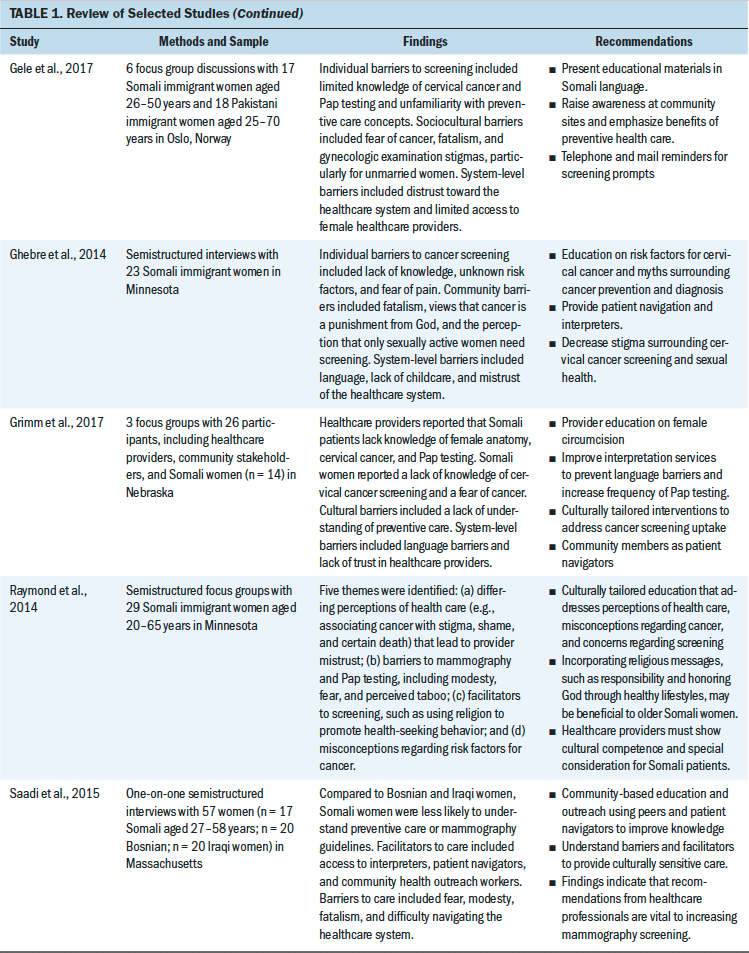

The 10 articles identified in the literature review were summarized based on study methods and sample, research findings, and recommendations. The author reviewed each article individually to extract and organize the data. An integrative review data analysis was performed by grouping research findings into emerging themes, and all articles were reviewed for thematic input. Based on the integrative review, cancer screening program initiative recommendations were developed and guided by the thematic elements. The results were compiled into a synthesis of evidence (see Table 1).

Results

Studies were published from 2007 to 2018. Qualitative methodology was used in all of the studies, including individual interviews, focus groups, or both. Study participants were recruited from clinic-based settings and community-based settings. Three studies took place in Europe (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Gele et al., 2017); the remaining seven studies took place in the United States (Al-Amoudi et al., 2013; Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015). Although some studies focused solely on breast or cervical cancer screening, some included data on screening for both cancers (Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014). Several studies questioned the patients on their health beliefs toward general preventive care in addition to cancer screenings (Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al, 2014; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015). Two studies included populations in addition to Somali women, but qualitative data analysis was performed separately (Gele et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). One study included interviews with healthcare providers and community stakeholders in addition to the Somali focus group (Grimm et al., 2017). The following four themes of evidence emerged from the literature review: (a) limited knowledge of breast and cervical cancer screenings, (b) health beliefs and sociocultural barriers to cancer screenings, (c) system-level barriers to cancer screenings, and (d) recommendations to facilitate screening and preventive care.

Limited Knowledge of Cancer Screenings

In this review, all 10 studies found that limited knowledge significantly influenced Somali women’s lack of breast and cervical cancer screening. In a study of 34 Somali women by Carroll et al. (2007), only 53% of women were familiar with the terms Pap test or pelvic examination, only 18% understood the purpose of mammography, and 74% did not recognize the word cancer. Grimm et al. (2017) reported that female Somali focus group participants and healthcare providers indicated that Somali women lack an understanding of female anatomy, the purpose of cervical cancer screening and the HPV vaccine, and the procedure for Pap testing. Abdullahi et al. (2009) and Addawe et al. (2018) found that first-generation Somali women reported unfamiliarity with cervical cancer screening before emigrating because Somalia had no organized screening program. In the study by Abdullahi et al. (2009), the majority of participants could not identify the purpose of a Pap test. Pap testing was also viewed as a diagnostic tool needed only when vaginal symptoms are present (Addawe et al., 2018). According to Al-Amoudi et al. (2013), Somali women report that cancer is rarely mentioned in Somali communities, leading to limited knowledge of breast cancer and mammography guidelines. Similarly, Gele et al. (2017) and Ghebre et al. (2014) found that their focus groups reported little knowledge of cervical cancer risk factors, screening recommendations, and cervical cancer prevention. Saadi et al. (2015) performed semistructured interviews with Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somali women. Based on the results, Somali women were least likely to understand the purpose of a mammogram, and those who correctly understood breast cancer screening had gained this knowledge since immigrating to the United States (Saadi et al., 2015). Misconceptions regarding risk factors also led to incorrect understanding of breast and cervical cancers, which may cause Somali women to believe they are less susceptible to cancer because of its cultural classification as a western disease (Ghebre et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014).

Health Beliefs and Sociocultural Barriers to Screening

Preventive care: Five studies found that Somali women do not adhere to cancer screening guidelines because they are unfamiliar with the concept of preventive health care (Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). In focus groups, Somali women reported that their primary understanding of health care consisted of symptomatic acute care and that they would be unlikely to undergo screening or seek a clinic visit without acute symptoms (Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). In the study by Gele et al. (2017), the majority of respondents believed that Pap testing should not be performed on women without symptoms of illness, which indicates lack of understanding of the preventive nature of cervical cancer screening. In addition, Saadi et al. (2015) found that 76% of participants in their study had no contact with physicians in Somalia and were unlikely to understand preventive care when compared to Bosnian and Iraqi refugees.

Fatalism: Religious beliefs were commonly cited as integral to the Somali perspective on health, illness, and death. Fatalism is a belief that, despite intervention, one cannot control one’s fate or destiny, which is often associated with fewer cancer screenings and delayed cancer treatment (Medscape, 2009). In eight studies, fatalism was identified as a salient theme (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015). Participants in the studies reviewed consistently stated that, whether they participated in healthcare prevention services, God’s will ultimately decides their fate. Some Somali women understood cancer to mean a fatal illness, and some participants reported that Somali women would rather not discuss cancer because of the fear and stigma surrounding such an illness (Carroll et al., 2007; Ghebre et al., 2014). Conversely, some participants believed their religious status as Muslims bestowed protection from cancer and, therefore, denied the need for preventive screening (Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014).

Modesty and taboo: Several studies found that modesty and taboo surrounding gynecologic examinations were a common barrier to screening uptake (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015). Participants in these studies also reported that they would be uncomfortable or unwilling to receive a gynecologic examination from a male healthcare provider, and that a lack of female healthcare providers constituted a barrier to care. Somali women in three studies also expressed concern that virginity may be compromised by undergoing Pap testing (Addawe et al., 2018; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014). In the Ghebre et al. (2014) study, participants believed that single women could be ostracized by their communities for undergoing Pap testing because it may be publicly perceived as an indication that they are sexually active outside of marriage. Female genital mutilation or circumcision, a common practice in Somali families, was mentioned in five studies as a barrier to cervical cancer screening uptake (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017). In many studies, participants stated that circumcision may cause pain during a gynecologic examination, make the examination impossible, or cause shame and embarrassment because of the healthcare provider’s reaction (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017).

System-Level Barriers to Screening

Commonly cited barriers to screening among Somali women included language barriers, difficulty navigating the healthcare system, distrust toward the healthcare system or providers, and financial costs (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014). In a study by Raymond et al. (2014), refugee women identified that a lack of transportation, previous work and childcare commitments, and financial costs kept women from obtaining preventive healthcare services. Somali women and healthcare providers in Grimm et al.’s (2017) study identified language as the primary barrier to increasing cervical cancer screenings. Several studies found that mistrust between Somali women and healthcare providers constituted a major barrier to screening uptake; Somali women reported that they did not believe that the healthcare system had their best interest in mind, and they often questioned the recommendations of their healthcare providers (Addawe et al., 2018; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014). Despite this, Somali women in several studies reported that they would be more likely to undergo cancer screening at the recommendation of their healthcare provider (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013).

Recommendations to Facilitate Screenings and Access to Preventive Care

Recommendations to facilitate breast and cervical cancer screenings included educating Somali women on preventive healthcare concepts and the importance of and methods for cancer screening (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013; Carroll et al., 2007; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014). Education should be culturally tailored to address barriers specific to Somali immigrant women and provided in Somali language (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Carroll et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014). Addawe et al. (2018) promoted partnerships among healthcare providers and faith community leaders to develop messaging that addressed religiously grounded concerns regarding cervical cancer and Pap testing, such as fatalism, modesty, and sexual taboo. Several studies suggested that Somali community members should be trained as health outreach workers or patient navigators to overcome social and health system barriers (Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). In many of the studies reviewed, community involvement was seen as essential to educating the Somali community on breast and cervical cancer screening (Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). Healthcare providers should also be educated on how to engage Somali women sensitively and effectively, as well as the importance of addressing screening recommendations at office visits (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015).

Discussion

Breast and cervical cancer screening continues to be underused among Somali immigrant women (Harcourt et al., 2013; Morrison et al.,2012). Qualitative research suggests that multiple barriers contribute to the continued gap between evidence-based screening recommendations and the current rate of screening in the Somali population. These barriers were consistently identified at the personal, cultural, and system levels across all 10 studies in this review. The predominant personal barriers discovered during the literature review included a lack of knowledge of mammography and Pap testing, as well as the importance of guideline-based cancer screening. All 10 studies reported that Somali women either self-reported a lack of knowledge or were unable to correctly identify important facts regarding breast and/or cervical cancer screening. In the studies included in this review, cultural barriers most often included the lack of a framework to understand preventive health care, fatalistic views toward illness and cancer, concerns about modesty, and a taboo regarding discussions of gynecologic health. Common barriers at the system level in this review included language barriers, mistrust of healthcare providers, financial concerns, and difficulty navigating the healthcare system. Suggested strategies to overcome these barriers were also consistent across the studies in this review. The synthesis of evidence suggests that offering culturally tailored education that addresses common barriers to cancer screening in the community setting may be effective in increasing breast and cervical cancer screening. Educating healthcare providers who frequently work with Somali patients on these barriers and facilitators may also be beneficial.

Recommendations for Screening Program Initiatives

This integrative review aims to provide key recommendations for future screening program initiatives involving Somali immigrant women, particularly in the United States where Somali immigrant communities are growing. Based on this integrative review, the author recommends that the following components be included in planning for breast and cervical cancer screening initiative programs for Somali immigrant women: (a) community involvement, (b) culturally and linguistically tailored health education, and (c) enhanced access to culturally sensitive care.

Community involvement: In four studies, community involvement was considered essential to cancer screening programs targeting Somali immigrants (Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). Efforts to obtain community buy-in for health education initiatives could include community-based participatory research methods, which have been strategically used in previous research efforts in relocated refugee communities, including Somalis (Filippi et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2009). These methods focus on collaborating among community partners, acknowledging community strengths, and leveraging these as facilitators to improve public health measures to create an atmosphere of mutual trust and engagement throughout the research process (Johnson et al., 2009). Other strategies to engage the Somali community in cancer screening initiatives involve training and including Somali community health workers when planning and executing education programs (Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Saadi et al., 2015). Community health workers have been studied in cancer screening efforts with ethnic minorities within the United States with favorable results (Wells et al., 2011). Another effort to increase community participation can be to host education programs within Somali community centers or mosques to provide a familiar environment and increase recruitment (Francis et al., 2014).

Culturally and linguistically tailored health education: Significant cultural, knowledge, and linguistic barriers to care were identified in this integrative review. Health education is needed to address the prevalence of inadequate knowledge of cancer, preventive health care, recommended cancer screenings, and screening guidelines. Six studies identified language issues as a significant barrier to cancer screening uptake (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013; Francis et al., 2014; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017); therefore, education offerings should be linguistically tailored, when possible. According to the NYS Statewide Language Regional Bilingual Education Resource Network (2012), dialects vary considerably throughout Somalia, and the ability to read Somali script is limited. Oral videos, presentations, and audio recordings may be more effective than written education handouts in this population (Abdullahi et al., 2009). Culture-specific issues, such as modesty, sexual taboo, religious concerns, and fatalism, should also be addressed in a sensitive manner to reduce barriers to cancer screening. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has created a series of culturally and linguistically tailored educational videos for Somali immigrant women covering a broad range of health topics, including cancer screening (Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2019). These videos are available for free and represent evidence-based resources for Somali health promotion initiatives.

Enhanced access to culturally sensitive care: If possible, community-based health promotion initiatives to increase female cancer screening among Somali women could involve partnering with local clinics and healthcare organizations to provide culturally sensitive care and affordable screening options. To mitigate any mistrust between Somali immigrant women and U.S. healthcare providers, culturally sensitive communication is vital (Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017). Access to female healthcare providers and interpreters is also essential to reducing feelings of shame and discomfort that are sometimes associated with gynecologic examinations (Francis et al., 2014; Gele et al., 2017). Healthcare providers should be educated on culturally specific healthcare beliefs and traditions of Somali culture, such as the importance of virginity for unmarried women and the prevalence of female circumcision (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Gele et al., 2017; Ghebre et al., 2014; Grimm et al., 2017; Raymond et al., 2014). Cultural sensitivity training can better prepare healthcare providers to navigate conversations regarding these topics, which are considered taboo within Somali culture. In addition, three studies indicated that provider recommendation for cancer screenings is a key facilitator to increasing screening uptake (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Al-Amoudi et al., 2013). Therefore, healthcare providers should be proactive in recommending cancer screening and educating Somali immigrant patients on the importance of evidence-based breast and cervical cancer screening. Addressing functional limitations, such as lack of childcare, transportation, and financial constraints, may also reduce barriers to screening (Addawe et al., 2018; Ghebre et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014; Saadi et al., 2015). Many healthcare systems offer services to underinsured or uninsured residents; connecting patients with community resources may facilitate cancer screening uptake.

Three studies in this review were performed in western European countries (Abdullahi et al., 2009; Addawe et al., 2018; Gele et al., 2017). Although the healthcare system in these countries differs from the United States, most notably in the availability of a national healthcare system, study findings regarding knowledge, cultural, and system-level barriers did not markedly vary from the study findings of research conducted in the United States. The findings suggest that offering free or affordable access to cancer screenings alone may not result in increased screening uptake. Instead, a multifaceted approach that addresses each barrier and facilitator to care should be used in screening program initiatives.

Limitations

A majority of the studies in this review used convenience sampling to recruit participants, which may have introduced bias into the research (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015). In addition, the qualitative studies reviewed may not adequately reflect the perceived needs, beliefs, barriers, and facilitators to care for all Somali immigrant women in the United States. Although qualitative research is helpful for understanding the experience of Somali immigrant women undergoing cancer screening and navigating the healthcare system, there is no guarantee that programs using these methods will result in increased Pap testing and breast cancer screening.

Implications for Research

Synthesizing the body of evidence regarding barriers and facilitators to cancer screening can provide nurse researchers and practitioners with valuable information to more effectively engage the Somali community in cancer screening initiatives. Nurses caring for this population must be aware of the health beliefs and cultural implications that influence breast and cervical cancer screening uptake among Somali women. Understanding the unique needs that Somali women may have when immigrating to western countries can provide a framework for health promotion in this population. Nurses and nurse practitioners often provide health education in primary care settings and are key stakeholders in community healthcare initiatives. As trusted healthcare professionals, nurses can build relationships that will help to influence their patients to engage in healthy behaviors. By implementing initiatives that consider the qualitative themes presented in this review, nurses have the opportunity to improve the health of Somali women at local, state, and national levels. Although this integrative review focused exclusively on barriers and facilitators to breast and cervical cancer screenings among Somali immigrant women, the author’s approach to synthesizing health beliefs and attitudes to inform future cancer screening programs may be used by other researchers seeking to reach different populations. Before designing and implementing public healthcare initiatives, nurse researchers should gain insight into minority and immigrant cultures. This review provides a guide to synthesizing evidence regarding cultural considerations for cancer screening programs.

Conclusion

This integrative review supports the use of culturally and linguistically tailored education delivered by healthcare providers in community settings as an evidence-based method to increase breast and cervical cancer screenings among Somali immigrant women. Decreasing barriers to screening, such as facilitating appointment scheduling, offering translation services, and dispelling myths surrounding cancer screening, may lead to increased screening uptake in Somali women. Enhancing facilitators to screening, such as improving culturally sensitive provider recommendations, using community health workers, improving access to female practitioners and interpreters, and using Somali community centers for screening and education programs, may also increase the frequency of Pap tests and mammograms received by Somali women. Interventions incorporating these qualitative themes are needed to further examine whether addressing these barriers and facilitators will increase cancer screening behaviors among Somali immigrant women.

About the Author(s)

Katie Huhmann, DNP, FNP-C, is a family nurse practitioner in Kansas City, MO. No financial relationships to disclose. Huhmann can be reached at katiehuhmann@hotmail.com, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted May 2019. Accepted August 1, 2019.)

References

Abdullahi, A., Copping, J., Kessel, A., Luck, M., & Bonell, C. (2009). Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health, 123(10), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011

Addawe, M.A., Mburu, C.B., & Madar, A.A. (2018). Barriers to cervical cancer screening: A qualitative study among Somali women in Oslo Norway. Health and Primary Care, 2(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.15761/hpc.1000128

Al-Amoudi, S., Cañas, J., Hohl, S.D., Distelhorst, S.R., & Thompson, B. (2013). Breaking the silence: Breast cancer knowledge and beliefs among Somali Muslim women in Seattle, Washington. Health Care for Women International, 36(5), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.857323

American Cancer Society. (2020a). How common is breast cancer? Retrieved January 24, 2020, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-…

American Cancer Society. (2020b). Key facts about cervical cancer. Retrieved January 24, 2020, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

Carroll, J., Epstein, R., Fiscella, K., Volpe, E., Diaz, K., & Omar, S. (2007). Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and preventive health care among Somali women in the United States. Health Care for Women International, 28(4), 360–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330601179935

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Cancer screening—United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(3), 41–45.

Filippi, M.K., Faseru, B., Baird, M., Ndikum-Moffor, F., Greiner, K.A., & Daley, C.M. (2012). A pilot study of health priorities of Somalis living in Kansas City: Laying the groundwork for CBPR. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(2), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9732-1

Francis, S.A., Griffith, F.M., & Leser, K.A. (2014). An investigation of Somali women’s beliefs, practices, and attitudes about health, health promoting behaviours and cancer prevention. Health, Culture and Society, 6(1), 1–12. http://doi.org/10.5195/hcs.2014.119

Gele, A.A., Qureshi, S.A., Kour, P., Kumar, B., & Diaz, E. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among Pakistani and Somali immigrant women in Oslo: A qualitative study. International Journal of Women’s Health, 9, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S139160

Ghebre, R.G., Sewali, B., Osman, S., Adawe, A., Nguyen, H.T., Okuyemi, K.S., & Joseph, A. (2014). Cervical cancer: Barriers to screening in the Somali community in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(3), 722–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0080-1

Grimm, B., Alnaji, N., Watanabe-Galloway, S., & Leypoldt, M. (2017). Cervical cancer attitudes and knowledge in Somali refugees in Nebraska. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 3(1, Suppl.), 81S–87S. https://doi.org /10.1177/2373379917698673

Harcourt, N., Ghebre, R.G., Whembolua, G.L., Zhang, Y., Warfa Osman, S., & Okuyemi, K.S. (2013). Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening behavior among African immigrant women in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(3), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4

Johnson, C.E., Ali, S.A., & Shipp, M.P.L. (2009). Building community-based participatory research partnerships with a Somali refugee community. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6, Suppl. 1), S230–S236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.036

Krogstad, J.M. (2019, October 7). Key facts about refugees to the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/07/key-facts-about-refuge…

Krogstad, J.M., & Radford, J. (2017, January 27). Key facts about refugees to the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/30/key-facts-about-refuge…

Medscape. (2009). Cancer fatalism and health disparities. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/707850

Melnyk, B.M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2015). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Morrison, T.B., Wieland, M.L., Cha, S.S., Rahman, A.S., & Chaudhry, R. (2012). Disparities in preventive health services among Somali immigrants and refugees. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(6), 968–974. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9632-4

NYS Statewide Language Regional Bilingual Education Resource Network. (2012). Somalia: Language and culture. New York University.

Office of Refugee Resettlement. (2019). Refugee health promotion and education. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/refugee-health-promotion-and-education

Raymond, N.C., Osman, W., O’Brien, J.M., Ali, N., Kia, F., Mohamed, F., . . . Okuyemi, K. (2014). Culturally informed views on cancer screening: A qualitative research study of the differences between older and younger Somali immigrant women. BMC Public Health, 14, 1188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1188

Saadi, A., Bond, B.E., & Percac-Lima, S. (2015). Bosnian, Iraqi, and Somali refugee women speak: A comparative qualitative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening. Women’s Health Issues, 25(5), 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.005

Wells, K.J., Luque, J.S., Miladinovic, B., Vargas, N., Asvat, Y., Roetzheim, R.G., & Kumar, A. (2011). Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention, 20(8), 1580–1598. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11- 0276

World Health Organization. (2014). Cancer country profile: Somalia. https://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/som_en.pdf

World Health Organization. (2015). Humanitarian response plans in 2015: Somalia. https://www.who.int/hac/donorinfo/somalia.pdf