Acceptability of a Dyadic Psychoeducational Intervention for Patients and Caregivers

Purpose: To assess participants’ acceptability of the FOCUS program, a psychoeducational intervention, delivered to multiple patient–caregiver dyads in a small-group format.

Participants & Setting: A total of 72 adults diagnosed with cancer and their caregivers (36 dyads) who participated in 1 of 11 FOCUS programs delivered at two Cancer Support Community affiliates.

Methodologic Approach: A pre-/postintervention design was used to implement the FOCUS program. The FOCUS Satisfaction Instrument measured participants’ satisfaction with the program, usefulness of the materials, helpfulness in coping with cancer, duplication of services, willingness to recommend the program to others, and the most and least beneficial aspects. Descriptive statistics, t tests, and content analysis were used.

Findings: Most participants reported that the program did not duplicate services, that it helped them cope with cancer, and that they would recommend the program to others. The most beneficial aspects of the program were the group format and the dyadic approach.

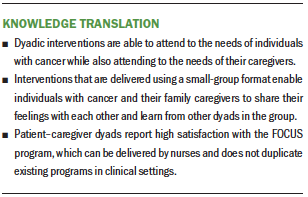

Implications for Nursing: A group format and dyadic approach to address the psychosocial impact of cancer is highly valued by individuals with cancer and their caregivers. Nurses are well positioned to lead implementation of programs like the FOCUS program that complement other cancer support services.

Jump to a section

The diagnosis of cancer affects the well-being and quality of life of individuals with cancer and their family caregivers (Ferrell & Wittenberg, 2017). As the demands placed on family caregivers increase, caregivers report higher emotional distress and lower quality of life, hindering their ability to provide high-quality patient care at home (Litzelman et al., 2016).

Dyadic programs are needed that treat the patient–caregiver dyad (i.e., the pair) as the unit of care. Dyadic programs should be based on the concept of interdependence and on prior research that indicates that responses to illness of patients with cancer and their family caregivers are significantly related; each person affects the other (Traa et al., 2015). Dyadic programs promote open patient–caregiver communication, encourage mutual support, foster effective dyadic coping, and provide education and support to help dyads manage the demands of illness (Baucom et al., 2012).

Most dyadic interventions have been delivered to individual patient–caregiver dyads (Ferrell & Wittenberg, 2017), with only a few delivered to multiple dyads using a small-group format (Dockham et al., 2016; Johns et al., 2019; Manne et al., 2016; Titler et al., 2017). Findings indicate that these dyadic interventions improve patient and caregiver outcomes by reducing depressive symptoms, anxiety, and distress (Johns et al., 2019; Manne et al., 2016; Titler et al., 2017) and by increasing self-efficacy, perceived benefits of illness, well-being, and quality of life (Dockham et al., 2016; Johns et al., 2019; Manne et al, 2016; Titler et al., 2017). However, despite these positive intervention effects, study enrollment rates can be low—such as 10.4%, as reported by Manne et al. (2016)—raising the question about the acceptability of dyadic, small-group interventions.

A systematic review by Ugalde et al. (2019) of cancer caregiver interventions and their potential for implementation into practice demonstrated that fewer than half of the 26 studies that met the review criteria contained evidence concerning the acceptability of interventions from the caregivers’ perspectives and only 2 addressed the potential adoption of interventions. To bridge the gap between research and practice, the acceptability of interventions to individuals with cancer and their caregivers and their potential for future adoption need to be assessed (Ugalde et al., 2019).

Objectives

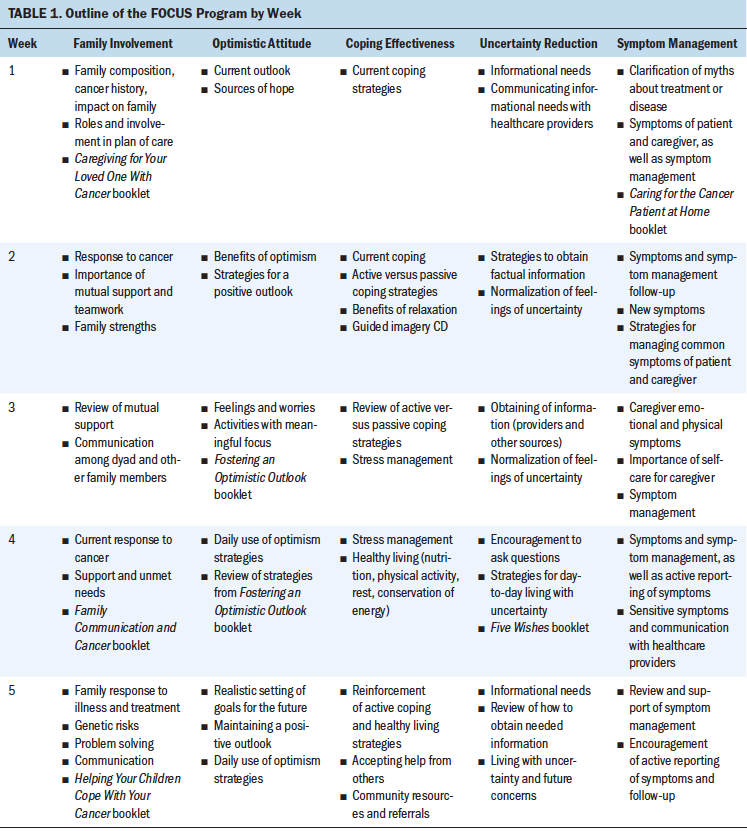

The current study assessed satisfaction (i.e., acceptability) of adults with cancer and their family caregivers (i.e., partners, family members) with the FOCUS program when delivered to multiple dyads using a small-group format. The FOCUS program is an evidence-based, psychoeducational intervention that addresses family involvement, optimistic attitude, coping effectiveness, uncertainty reduction, and symptom management (see Table 1); it was tested in three randomized clinical trials (N = 947 patient–caregiver dyads) and demonstrated efficacy in improving outcomes (e.g., emotional distress, quality of life) of individuals with cancer and their caregivers (Northouse et al., 2005, 2007, 2013). The FOCUS program has also demonstrated effectiveness when implemented using a group delivery format in Cancer Support Community (CSC) sites in three diverse locations in the United States (Dockham et al., 2016; Titler et al., 2017).

This article reports participants’ satisfaction and feedback concerning the FOCUS program when delivered to multiple dyads in a small-group format at CSC affiliates in California and Ohio (Titler et al., 2017). Research questions were as follows:

• What is the level of satisfaction of participants taking part in the five-week group-delivered FOCUS program?

• What is the perceived usefulness of material resources participants received during the FOCUS program?

• Were there significant differences between the satisfaction and usefulness scores of individuals with cancer and their caregivers?

• What were participants’ perceptions regarding the FOCUS program (a) duplicating services offered by their cancer treatment center, (b) assisting them to cope with cancer, and (c) recommending the program to others facing cancer?

• What did participants perceive as the most beneficial and least beneficial aspects of the program?

Methods

Sample and Setting

Satisfaction and feedback findings about the FOCUS program are from participants of a multisite implementation study at two CSC sites in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Santa Monica, California (Titler et al., 2017). The CSC is a large network of community agencies in the United States that provides professional psychosocial care in a group format at no cost to individuals with cancer and their family caregivers. The racial mix at the Cincinnati CSC site is principally Caucasian (81%) and African American (11%), whereas the racial mix at the Santa Monica CSC site is Caucasian (69%), Asian (11%), and Hispanic (7%).

Individuals with cancer were eligible to participate in the FOCUS program if they were aged 18 years or older, had been diagnosed with any type of cancer, were currently in treatment or had completed treatment in the past 18 months, and had a caregiver willing to participate in the study. Caregivers were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older and identified by the person with cancer as their primary family caregiver. A family caregiver was defined as the individual who provided emotional and/or physical support to the person with cancer without pay. Caregivers were excluded from participation in the study if they had been diagnosed with cancer in the previous year or if they were receiving active treatment for cancer. The enrollment rate was 71%, and the retention rate was high, at 90% (Titler et al., 2017).

The FOCUS program was delivered by licensed, trained social workers from each site using a group format of three to four dyads (six to eight people) with five weekly face-to-face sessions, each lasting two hours (Titler et al., 2017). A total of 11 FOCUS programs, with each program comprised of five sessions, were delivered during 12 months to 36 dyads (72 adults) (Titler et al., 2017).

A pre-/postintervention design (no control group) was used to implement the FOCUS program; quantitative and qualitative data were obtained. The methods of the multisite implementation study and informed consent process are reported in detail elsewhere (Titler et al., 2017).

Instruments

Satisfaction was measured by the FOCUS Satisfaction Instrument, which was used in previous studies and has demonstrated content validity and reliability of 0.87–0.89 for individuals with cancer and 0.89–0.93 for caregivers (Dockham et al., 2016; Harden et al., 2009; Northouse et al., 2002). The instrument consists of two parts: (a) seven items for rating participants’ satisfaction with components of the program on a scale of 1 (not satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) and (b) seven items for rating the usefulness of the resource materials received on a scale of 1 (not useful) to 5 (very useful). Items in each of the two parts are summed and divided by seven to arrive at a total satisfaction score. The instrument includes additional questions that assess if the program helped participants cope with cancer (no, unsure, yes); if it duplicated any services offered by their cancer treatment center (no, yes); and if participants would recommend the program to others facing cancer (no, unsure, yes). It also included open-ended questions asking about the most and least beneficial aspects of the program. The satisfaction instrument was the same for the person with cancer and the caregiver.

Demographic questions assessed participants’ age, gender, marital status, race, education, income, and employment status. Other questions assessed patients’ type and stage of cancer and whether they were currently receiving cancer treatment.

Data Collection

Participants’ demographic and medical information was collected prior to commencement of the FOCUS program. The FOCUS Satisfaction Instrument was administered on completion of the last (i.e., fifth) session of the FOCUS program. Individuals with cancer and their caregivers completed questionnaires independently and placed them in sealed envelopes. Personnel at each CSC site collected the sealed envelopes and returned them to the investigative team.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Follow-up exploratory analyses were conducted using t tests to determine if there were differences in the satisfaction and usefulness scores of individuals with cancer and their caregivers.

Statements regarding most and least beneficial aspects of the FOCUS program were analyzed using qualitative techniques (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis was used to group data into response patterns (Pope & Mays, 2006). Interrater reliability was obtained by having two of the current authors (M.G.T. and C.S.) independently code and cluster similar statements into categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Statements within categories were compared, and differences were reconciled by another of the current authors (L.N.). Categories were then named with a theme that best reflected the statements within each category.

Results

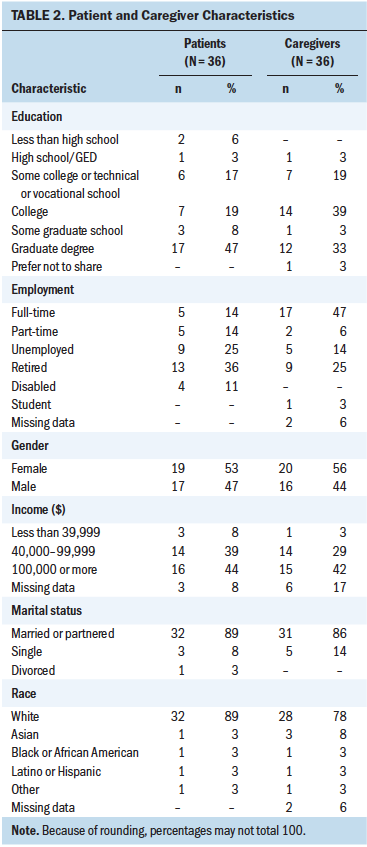

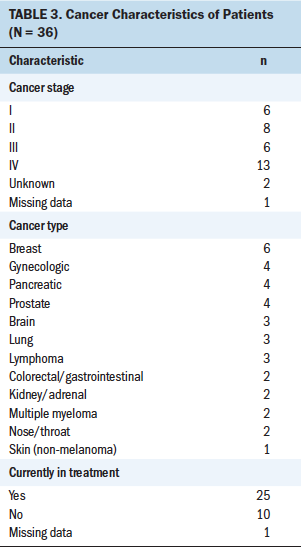

Demographics of participants (N = 36 dyads) are summarized in Table 2. The mean age of individuals with cancer was 60.8 years (SD = 14.2, range = 18–88 years) and 55.9 years (SD = 15.1, range = 19–83 years) for caregivers. Most individuals with cancer and their caregivers were female and either married or partnered. Most individuals with cancer had stage II or IV cancer and were currently in treatment (see Table 3).

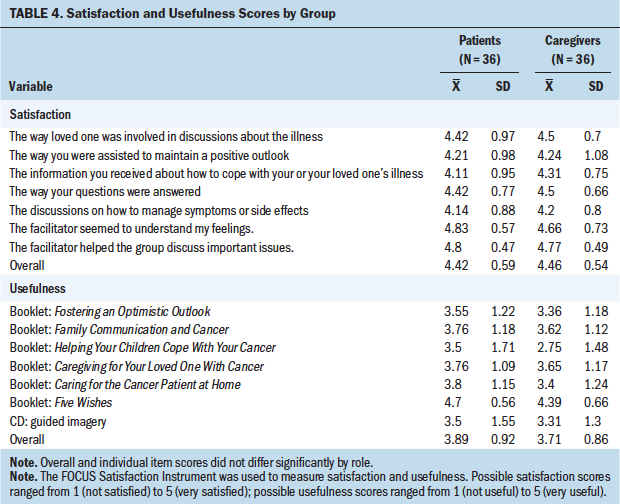

Overall program satisfaction scores for individuals with cancer and their caregivers were more than 4.4 on a 5-point scale; overall usefulness scores were somewhat lower among both groups (3.89 for individuals with cancer and 3.71 for caregivers). Overall and individual item scores did not differ significantly by role (see Table 4). Satisfaction items rated the highest by both groups concerned the group facilitator: “The facilitator seemed to understand my feelings” and “The facilitator helped the group discuss important issues.” The resource with the highest usefulness rating was the Five Wishes booklet that provides a foundation to discuss spiritual and emotional needs, as well as advance care planning, during a serious illness.

A majority of individuals with cancer and their caregivers (85% of each group) reported that the FOCUS program did not duplicate services provided at their cancer treatment center, and most reported that the program helped them cope with cancer (individuals with cancer = 86%, caregivers = 81%). Almost all participants reported that they would recommend the program to others facing cancer (individuals with cancer = 91%, caregivers = 94%).

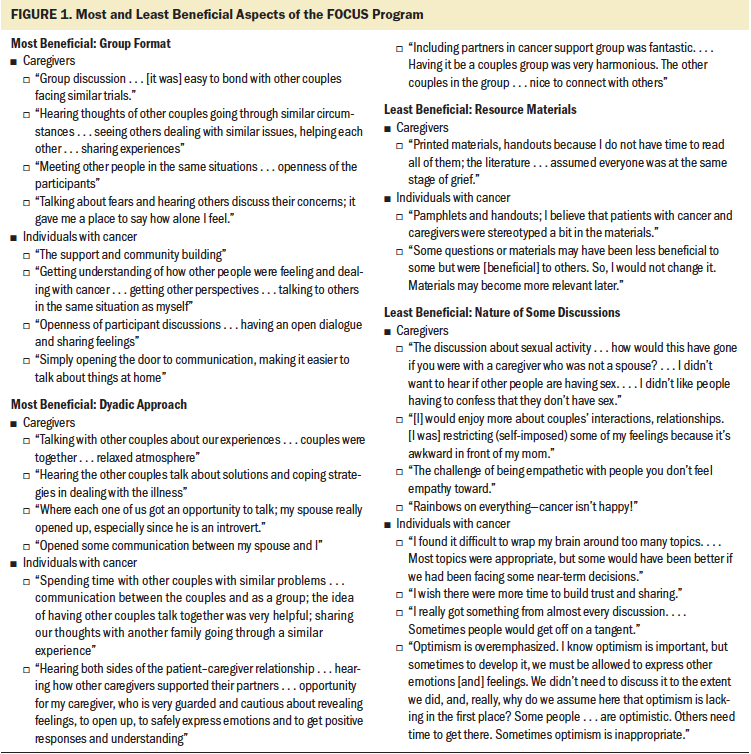

Comments regarding the most beneficial aspects of the FOCUS program centered on two major themes: the group format and the dyadic approach (see Figure 1). Two themes were also identified from comments regarding the least beneficial aspects of the program: the use of resource materials and the nature of some discussions.

Discussion

Individuals with cancer and their caregivers were highly satisfied with the FOCUS program. An important aspect of the FOCUS program, according to quantitative and qualitative data, was the group format that fostered open discussions among others who were also dealing with a cancer diagnosis. For example, participants noted the benefits of being able to talk openly about their fears while also hearing about others’ concerns, as well as the openness and the ease of bonding while talking with other patient–caregiver dyads in similar situations. This is supported by satisfaction scores for specific items such as “The way your questions were answered” (average score of greater than 4.4 for both groups), as well as “The facilitator seemed to understand your feelings” and “The facilitator helped the group discuss important issues” (average scores of greater than 4.6 for both groups). These findings are consistent with the therapeutic processes underlying other small-group interventions that foster peer support, the opportunity to openly discuss feelings in a safe environment among others in a similar situation, and the ability to learn effective coping strategies from others (Manne et al., 2016).

Of high value was the dyadic approach that enabled individuals with cancer and their caregivers to participate in the program together. The program gave each of them (the individual with cancer and the caregiver) the opportunity to talk, allowed the caregiver (not just the individual with cancer) to express feelings and receive support, opened up communication between the individual with cancer and the caregiver, helped them learn about solutions and coping strategies, and enabled them to hear about both sides of the patient–caregiver relationship. These findings underscore the important core components of dyadic interventions and the goal of assisting the individual with cancer while also attending to the well-being of the caregiver (Baucom et al., 2012; Sher, 2012). In the current study, individuals with cancer reported twice as many positive comments about the dyadic approach compared to caregivers, perhaps reflecting that this program stimulates and facilitates discussions with their caregiver that they previously may have been reluctant to initiate. This is supported by high satisfaction scores for the item “The way loved one was involved in discussions about the illness” (average score of greater than 4.4 for both groups).

These positive findings are similar to those from a pilot study by Johns et al. (2019), who reported high participant satisfaction for a dyadic group mindfulness intervention to support quality of life and advance care planning for individuals with metastatic cancer (N = 13 dyads). In the Johns et al. (2019) study, the enrollment rate was 59% and the retention rate was 85%, indicating that once dyads enrolled, they were likely to continue with the program, which suggests that they found the program helpful.

The moderate usefulness ratings of resource materials in the current study may be attributable to participants’ preference for open dialogue with the other dyads; participating in this conversation could have been thought of as more rewarding than reading the materials. Some resources, such as the Helping Your Children Cope With Your Cancer booklet, may have been less relevant to the older participants in the current study (the mean age of individuals with cancer in the current study was 60.8 years). The resource materials provided general information for individuals with cancer and their caregivers, rather than information tailored to the individual dyads; participants may have preferred resources that were more tailored to their unique situation (e.g., stage of grief). The Five Wishes booklet received a higher usefulness score than the other resource materials, perhaps because it is a more tailored document that takes into consideration the specific wishes of each person with cancer regarding medical treatment and end-of-life care planning.

In contrast, Johns et al. (2019) found that individuals with cancer and their caregivers rated highly the resources used for their dyadic group mindfulness intervention, responding positively to the following item: “The CDs and printed materials I received helped me to practice.” This wording suggests that the resources were closely related to carrying out the mindfulness exercises. These differences in study findings may be attributed to the nature of the psychoeducational intervention, the differences in the purpose of the resources, and the nature of the questions asked.

Group discussions related to sexuality were reported as less beneficial by two caregivers in the current study. Although the effects of cancer on sexual well-being and intimacy are important areas of need for many individuals with cancer and their caregivers (Girgis et al., 2013), discussing sexual well-being in a group setting may have been uncomfortable for these participants. In a study by Morse et al. (2014) that evaluated the support group topic preferences of individuals with cancer and their caregivers, dealing with treatment choices, anxiety, uncertainty, and stress received higher ratings than did dealing with issues related to sexuality. In addition, two participants in the current study preferred less emphasis on optimism. The qualitative comments about optimism are supported by the moderate scores from individuals with cancer and their caregivers regarding the Fostering an Optimistic Outlook booklet (3.55 and 3.36, respectively). Optimism may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is helpful for people to have some optimism—that is, to feel that there is some hope in their lives. However, on the other hand, the term “optimism” may suggest to others that they need to minimize feelings of sadness and loss, which are a common part of the cancer experience. Findings suggest that the positive and negative aspects of optimism need to be carefully addressed in future programs.

A hallmark of high satisfaction is a participant’s desire to recommend the program to others with similar circumstances. The overwhelming majority of participants in the current study noted that they would recommend the FOCUS program to others. Similarly, Johns et al. (2019) found that individuals with cancer and their caregivers were extremely likely to recommend the program to a friend or family member in a similar situation. In addition, the FOCUS program was complementary to, rather than duplicative of, the services available at the participants’ cancer treatment center and helped them cope with cancer. These are important findings to foster the spread and sustainability of evidence-based programs, such as the FOCUS program, to address the psychosocial needs of individuals with cancer and their caregivers.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include lack of racial and ethnic diversity and the relatively small sample size. In addition, participants had a relatively high level of education, with the majority having a college degree or higher. It is unknown whether participant satisfaction would be similar for a more ethnically diverse and less educated sample. Also, the FOCUS program was implemented only at CSC sites, which provide supportive cancer care free of charge to participants. Satisfaction of participants who receive the FOCUS program in other types of settings (e.g., church-affiliated settings, community cancer centers) is unknown. Perceptions of participants from hard-to-reach and vulnerable populations are unknown.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses or social workers who are educated about delivery of the FOCUS program can serve as facilitators. Implications for practice are fourfold. First, nurses must be mindful that the cancer experience includes caregivers. Consequently, a couples approach to address the psychosocial impact of cancer is merited and is highly valued by individuals with cancer and their caregivers. Second, the FOCUS program was not duplicative of the services participants received at their cancer center. Cancer treatment settings do not typically offer psychoeducational interventions to address the emotional and psychological distress of living with cancer. This requires that nurses collaborate with CSC affiliates or other community agencies in their local area to provide individuals with cancer and their caregivers the help they need to address these issues. Third, nurses need to take the lead in implementing programs like the FOCUS program in their practice agency and/or community. The authors of the current study have developed training materials for delivery of the FOCUS program to multiple dyads in a small-group format as well as an implementation manual to foster widespread uptake. (These materials are available from the first author.) Fourth, assessment of participant satisfaction is an essential part of evaluating psychoeducation interventions to determine if the intervention is meeting participants’ expectations.

Future nursing research should include measurement of participants’ satisfaction when testing the efficacy or effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for dyads delivered in a group format. Future implementation studies with the FOCUS program should explicate the mechanisms for reaching underserved and hard-to-reach populations; the satisfaction of participants and the usefulness of materials used will be important to evaluate. Given the effectiveness of and satisfaction with the FOCUS program, additional studies are needed to examine the best methods for spreading the implementation and sustainability of the FOCUS program to multiple community-based settings.

Conclusion

The FOCUS program is an evidence-based, dyadic psychoeducation program for adults with cancer and their family caregivers. Delivery in a group format resulted in high satisfaction and multiple benefits for the participants. Satisfaction findings from the current study in conjunction with the demonstrated effectiveness of the FOCUS program to improve quality of life, emotional and functional well-being, and distress at an estimated cost of $165 per dyad (Titler et al., 2017) provide a solid foundation for dissemination and implementation of this program. Individuals with cancer and their caregivers are not receiving the support they need to cope with the detrimental effects of their illness on quality of life. A national public policy is warranted to provide payment structures for delivery of the FOCUS program to individuals with cancer and their caregivers and to implement the FOCUS program in communities where people can derive optimal benefit.

About the Author(s)

Marita G. Titler, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor and Rhetaugh G. Dumas Endowed Chair, and Clayton Shuman, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor, both in the School of Nursing at the University of Michigan; Bonnie Dockham, LMSW, is the executive director of the Cancer Support Community of Greater Ann Arbor; Melissa Harris, BSN, RN, is a PhD student investigator, and Laurel Northouse, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor emerita, both in the School of Nursing at the University of Michigan, all in Ann Arbor. This study was funded by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research Pilot Grant Program of the University of Michigan (UL1TR000433). Titler, Shuman, Dockham, and Northouse contributed to the conceptualization and design. Titler, Shuman, and Dockham completed the data collection. Titler and Shuman provided statistical support. Titler, Shuman, and Northouse provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Titler can be reached at mtitler@umich.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2019. Accepted January 9, 2020.)

References

Baucom, D.H., Porter, L.S., Kirby, J.S., & Hudepohl, J. (2012). Couple-based interventions for medical problems. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.008

Dockham, B., Schafenacker, A., Yoon, H., Ronis, D.L., Kershaw, T., Titler, M., & Northouse, L. (2016). Implementation of a psychoeducational program for cancer survivors and family caregivers at a cancer support community affiliate: A pilot effectiveness study. Cancer Nursing, 39(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000311

Ferrell, B., & Wittenberg, E. (2017). A review of family caregiver intervention trials in oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67(4), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21396

Girgis, A., Lambert, S.D., McElduff, P., Bonevski, B., Lecathelinais, C., Boyes, A., & Stacey, F. (2013). Some things change, some things stay the same: A longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers’ unmet supportive care needs. Psycho-Oncology, 22(7), 1557–1564. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3166

Harden, J., Falahee, M., Bickes, J., Schafenacker, A., Walker, J., Mood, D., & Northouse, L. (2009). Factors associated with prostate cancer patients’ and their spouses’ satisfaction with a family-based intervention. Cancer Nursing, 32(6), 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b311e9

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Johns, S.A., Beck-Coon, K., Stutz, P.V., Talib, T.L., Chinh, K., Cottingham, A.H., . . . Helft, P.R. (2019). Mindfulness training supports quality of life and advance care planning in adults with metastatic cancer and their caregivers: Results of a pilot study. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 37(2), 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119862254

Litzelman, K., Kent, E.E., Mollica, M., & Rowland, J.H. (2016). How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34(29), 3554–3561. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3434

Manne, S.L., Siegel, S.D., Heckman, C.J., & Kashy, D.A. (2016). A randomized clinical trial of a supportive versus a skill-based couple-focused group intervention for breast cancer patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 668–681. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000110

Morse, K.D., Gralla, R.J., Petersen, J.A., & Rosen, L.M. (2014). Preferences for cancer support group topics and group satisfaction among patients and caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 32(1), 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2013.856058

Northouse, L., Kershaw, T., Mood, D., & Schafenacker, A. (2005). Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology, 14(6), 478–491. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.871

Northouse, L.L., Mood, D.W., Schafenacker, A., Kalemkerian, G., Zalupski, M., LoRusso, P., . . . Kershaw, T. (2013). Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology, 22(3), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3036

Northouse, L.L., Mood, D.W., Schafenacker, A., Montie, J.E., Sandler, H.M., Forman, J.D., . . . Kershaw, T. (2007). Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer, 110(12), 2809–2818. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23114

Northouse, L.L., Walker, J., Schafenacker, A., Mood, D., Mellon, S., Galvin, E., . . . Freeman-Gibb, L. (2002). A family-based program of care for women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29(10), 1411–1419. https://doi.org/10.1188/02.ONF.1411-1419

Pope, C., & Mays, N. (2006). Qualitative research in health care (3rd ed.). Blackwell.

Sher, T.G. (2012). What, why, and for whom: Couples interventions: A deconstruction approach. Behavior Therapy, 43(1), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.006

Titler, M.G., Visovatti, M.A., Shuman, C., Ellis, K.R., Banerjee, T., Dockham, B., . . . Northouse, L. (2017). Effectiveness of implementing a dyadic psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and family caregivers. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(11), 3395–3406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3758-9

Traa, M.J., De Vries, J., Bodenmann, G., & Den Oudsten, B.L. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: A systematic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12094

Ugalde, A., Gaskin, C.J., Rankin, N.M., Schofield, P., Boltong, A., Aranda, S., . . . Livingston, P.M. (2019). A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: Appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psycho-Oncology, 28(4), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5018