Survivorship Care Plan Preferences and Utilization Among Asian American Breast Cancer Survivors

Problem Identification: The survivorship care plan (SCP) is an individualized document with cancer diagnosis, treatment, surveillance, and health promotion recommendations. This integrative review synthesizes the extant literature to understand preferences and utilization of SCPs among Asian American survivors.

Literature Search: The CINAHL®, Embase®, PsycINFO®, and PubMed® databases were searched for articles about Asian American women with breast or cervical cancer and SCPs.

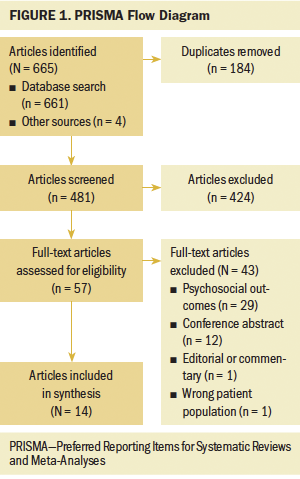

Data Evaluation: Two independent reviewers evaluated 481 titles and abstracts according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of those 481 titles and abstracts, 14 articles were selected for inclusion.

Synthesis: There was little evidence surrounding utilization of SCPs. Articles identified addressed only survivors of breast cancer, predominately of Southeast Asian descent. Asian American women with breast cancer reported preferences surrounding their survivorship needs. Barriers to delivery of the SCP were related to socioeconomic factors.

Implications for Research: There is a paucity of information guiding evidence-based delivery of SCPs in the vastly heterogenous population of Asian American survivors. More work is needed to provide high-quality care to these survivors.

Jump to a section

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death for Asian American women, followed by lung, colorectal, and corpus and uterine cancers (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2018). Although Asian American women tend to have lower breast cancer incidence and mortality rates (101 and 12.2 per 100,000, respectively) compared to White and Black women (127.5 and 19.2 per 100,000, respectively, for White women; 121.2 and 26.8 per 100,000, respectively, for Black women) (U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2018), Asian American women have experienced a rapid increase in breast cancer incidence in the past decade, with the highest rate increase among Korean and Southeast Asian women (Gomez et al., 2017). Cambodian and Lao women have cervical cancer incidence rates that are two to three times higher than those of White women (15.3 and 24.8 per 100,000 versus 8.1 per 100,000, respectively) (Miller et al., 2008). In addition, Asian Americans are the fastest growing population in the United States and are comprised of 19 Asian ethnic subgroups from East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021; Hoeffel et al., 2012). The U.S. Asian population increased by 81% between 2000 and 2015, with the largest ethnic groups being Chinese, Indian, and Filipino (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). About 60% of Asians in the United States are foreign-born (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Cancer risk increases after 10 years of living in the United States, bringing Asian American breast cancer incidence rates similar to those of non-Hispanic White women (Gomez et al., 2013). As the sensitivity of screen-detectable cancers (e.g., breast, cervical) increases and as the number of Asian Americans with cancer rises, healthcare providers must be equipped with knowledge of the survivorship needs of and relevant mitigation strategies for this heterogeneous group.

Asian American women who are diagnosed with a life-limiting, chronic disease like cancer find themselves negotiating how they should manage their lives with cancer. More than a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine recommended that every person living with a cancer diagnosis receive an individualized survivorship care plan (SCP) that summarizes their diagnosis and treatment, as well as details about their ongoing cancer surveillance plan, additional monitoring, cancer screening recommendations, and health maintenance advice (Hewitt et al., 2006). There is great variation across healthcare sites in terms of what SCPs should look like and how they should be delivered (Jacobsen et al., 2018). Every patient is also not guaranteed to receive an SCP from either their oncology or primary care teams (Mayer et al., 2015). The American Society of Clinical Oncology developed a statement that intended to emphasize the need for a standard but modifiable SCP template, identifying barriers that may exist in delivering the SCP effectively and ensuring the patient-centeredness of each SCP (Mayer et al., 2014). However, action addressing the statement has yet to bring widespread adoption of SCP best practices (Cowens-Alvarado et al., 2013; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2021). The American College of Surgeons (2019) Commission on Cancer no longer requires that SCPs be provided to individuals living with a cancer diagnosis; instead, the 2020 standards recommend and encourage that each patient be provided with an SCP as part of the comprehensive care plan offered by the survivorship care team to meet the needs of survivors.

To deliver a patient-centered SCP, it is necessary to acknowledge sociocultural influences on cancer survivorship in Asian women (Saha et al., 2003). This involves application of the concepts of cultural competence and cultural humility to the care of these women. Cultural competence is defined as possession of knowledge and skills to provide culturally congruent care (Marion et al., 2016). Cultural humility is a commitment to lifelong learning about one’s own biases and other cultures, as well as adapting to and advocating for the needs of patients and their families (Campinha-Bacote, 2019). In addition, studies have shown that cancer survivorship care may be influenced by the effects of limited English proficiency, immigration status, and respect for authority figures (Singh-Carlson et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2013). Among Asian American women diagnosed with breast cancer in California, a state with a large Asian population, 67% face additional challenges because of their immigration status (Wu et al., 2013). Incorporation of a culturally humble delivery of the SCP may reduce barriers for some Asian Americans who are diagnosed with breast and cervical cancer as they seek high-quality survivorship care (Lee et al., 2012).

Asian Americans are heterogeneous; therefore, delivering a culturally tailored SCP to each one of these ethnic subgroups is unrealistic (Wints & Handzo, 2014). However, given that the purpose of the SCP is to communicate information pertinent to cancer history and follow-up care, fostering culturally humble care is warranted. Sensitivity to cultural variation across Asian American groups can serve as the foundation of culturally competent communication between patients and healthcare providers (Teal & Street, 2009). The purpose of this review is to summarize existing literature describing preferences and utilization of SCPs for breast and cervical cancer in Asian American women. Synthesizing and disseminating the literature on sociocultural considerations in SCP delivery will begin a trajectory toward meeting the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendation.

Methods

An integrative review of knowledge related to breast cancer survivorship care planning was performed to better understand preferences, utilization, and barriers in Asian American women (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Electronic database inquiries in CINAHL®, Embase®, PsycINFO®, and PubMed® were conducted. Keywords and headings related to SCPs, breast cancer, and cervical cancer were used to identify articles eligible for inclusion (i.e., articles containing data related to Asian American adult survivors of breast or cervical cancer and SCP use). Each article was read and evaluated in depth for concepts related to Asian American women’s cancer survivorship experiences. Articles were excluded if the study population was less than 50% Asian American, if they had samples of mixed race or ethnicity with aggregated data, and if the samples included individuals being screened for a cancer, or non-American or pediatric populations.

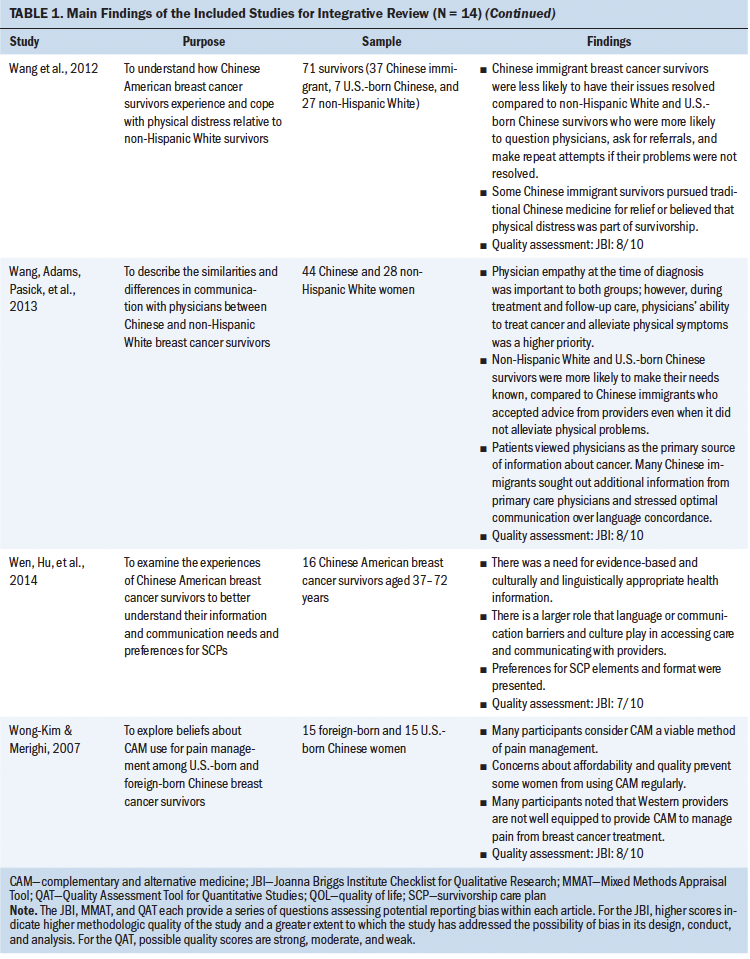

Two of the current authors extracted data from the included articles and critically appraised the quality of each study using the Joanna Briggs Institute (2017) Checklist for Qualitative Research and the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies from the Effective Public Health Practice Project (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, n.d.). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to evaluate mixed-methods studies (Hong et al., 2018). The current authors discussed emergent themes from the articles and agreed on those most relevant for inclusion. The results of this assessment are summarized in Figure 1.

Results

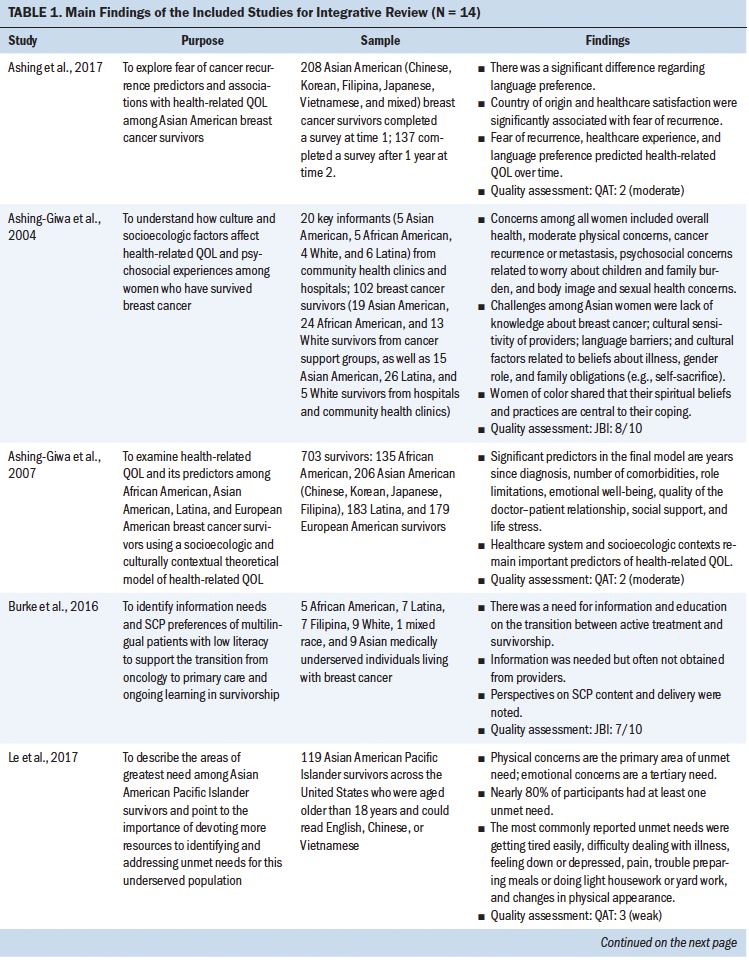

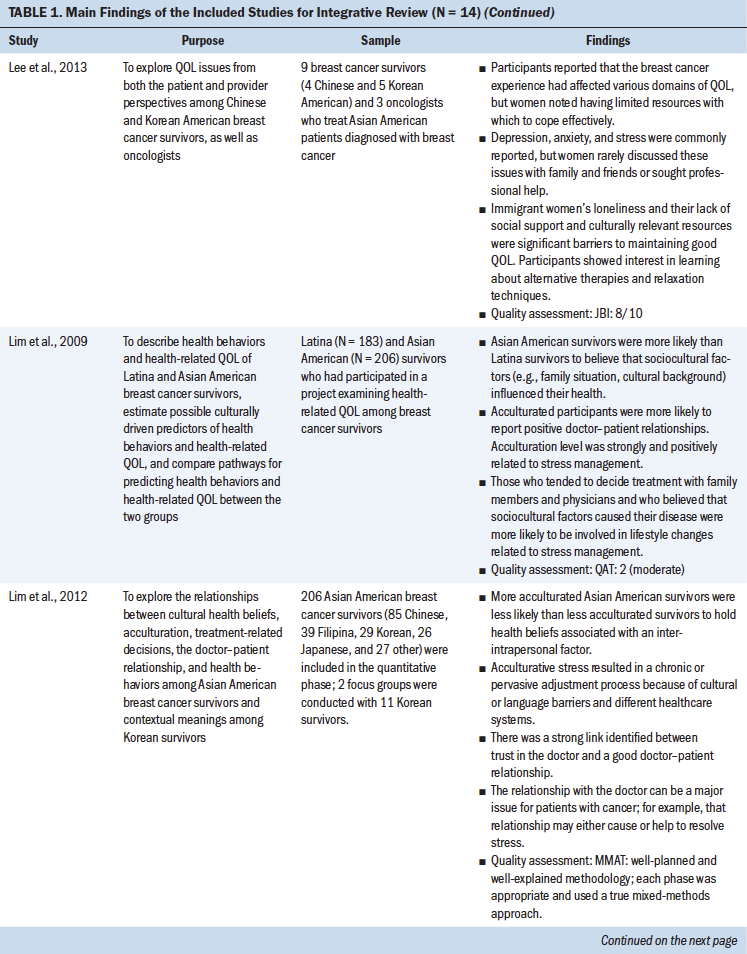

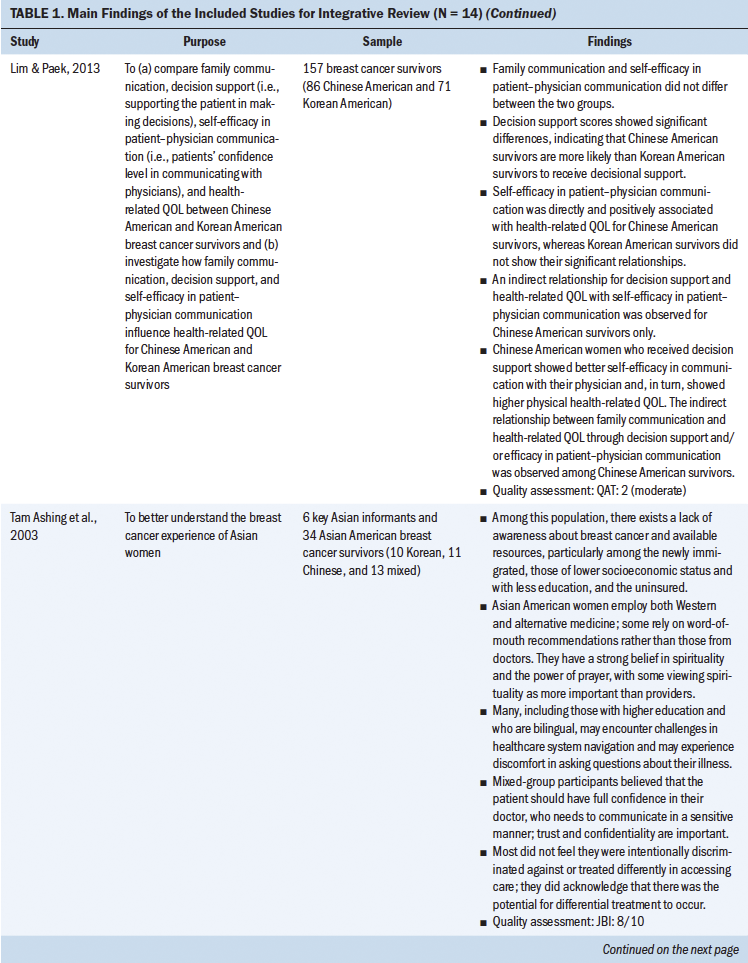

The 14 selected articles that met the inclusion criteria are described in Table 1. Eight used a qualitative methodology, five used a quantitative methodology, and one used a mixed methodology. Across these 14 articles, there were a total of 725 unique Asian American survivors of breast cancer, given that four of the articles detailed information derived from one study (Ashing et al., 2017; Ashing-Giwa et al., 2007; Lim et al., 2009, 2012) and 14 Asian American key informants (oncology clinicians) who provided perspectives on Asian American cancer survivorship experiences. No studies addressed cervical cancer survivorship. The majority of participants in the studies identified as Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Filipina, with two studies including first-generation immigrants (Wang et al., 2012; Wong-Kim & Merighi, 2007). The mean age of breast cancer survivors ranged from 28 to 77 years. Samples within these articles were generally educated, with a majority completing high school education or beyond.

Only two studies explicitly addressed SCP plans (Burke et al., 2016; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). The included articles addressed only breast cancer survivorship. Most articles discussed preferences for survivorship care and barriers that Asian American women encountered when receiving survivorship care.

Preferences in Survivorship Care and Needs

Asian American women with breast cancer reported preferences surrounding their survivorship care and needs, including cultural humility, psychosocial concerns, and spirituality.

Cultural humility: This review revealed that Asian Americans require healthcare providers to approach their survivorship care and implementation of the SCP with cultural humility, understanding that norms, practices, and beliefs may differ across Asian American subgroups. Largely, this consisted of sensitivity toward cultural factors, specifically language, etiquette with healthcare providers, gender roles, and openness to Eastern medicine. Language preferences were most commonly reported. Ashing et al. (2017) found that among a diverse sample of Asian Americans, there was a difference in language preference, with Chinese women being more likely to prefer to speak with healthcare providers in their native language about emotional issues than other Asian women in the study (i.e., Korean, Filipina, Japanese, and Vietnamese). Other Asian American participants identified the need for culturally appropriate English and non-English formatting of evidence-based survivorship information (Burke et al., 2016; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). However, Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al. (2013) identified that many Chinese immigrants in their study reported seeking additional health information that was communicated well, rather than solely seeking language concordance, indicating that health literacy is important to consider and warrants additional research.

Sociocultural norms with healthcare providers during survivorship visits were evident. Women spoke about their affinity to shy away from asking questions or to be passive with healthcare providers out of respect (Wang et al., 2012; Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al., 2013; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). Lim and Paek (2013) noted that self-efficacy in patient–provider communication among Chinese and Korean Americans did not differ. Tam Ashing et al. (2003) noted that sociocultural norms sometimes led to women agreeing to recommendations and later, because of discomfort, not following through with the recommendations. However, in a comparison of Chinese immigrants and non-Hispanic White individuals, Wang et al. (2012) found that each group reported physical concerns equally. Tam Ashing et al. (2003) and Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al. (2013) noted that U.S.-born Asians and those who were more acculturated were more likely to speak to healthcare providers about concerns than Asian immigrants or U.S.-born Asians who were less acculturated. In addition, Asian American women valued having time with healthcare providers (Tam Ashing et al., 2003; Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al., 2013; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). Chinese Americans prioritized a healthcare provider’s ability to alleviate their physical symptoms during treatment and follow-up care, particularly physicians’ ability to treat cancer (Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al., 2013). In one multiethnic study, Chinese women expressed the desire for culturally appropriate guidance on discussing their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment with their family (Burke et al., 2016). This is particularly important given that Asian Americans generally believe that healthcare providers control their health to some degree (Lim et al., 2012). Cultural norms would suggest that Asian Americans are private and prefer to avoid burdening their families.

Gender roles were noted among the articles, in that Asian American women held family caregiving in the highest esteem over personal health, despite living with breast cancer (Tam Ashing et al., 2003). Traditional gender roles were more pronounced in older women and those who had lower socioeconomic status (Tam Ashing et al., 2003). Public privacy was also important to these women in that women preferred to depend on their families (Lee et al., 2013; Tam Ashing et al., 2003), which was even more important in making decisions about care, given that such decisions are often made by the entire family in some cultures (Lim et al., 2009, 2012). In communication, even within the family, information and decisional support is variable across Asian American groups (Lim & Paek, 2013).

Openness to complementary and alternative medicine (e.g., traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture) was a consideration for the mitigation of adverse effects and improvement in immune function among this population of diverse cancer survivors (Lee et al., 2013; Tam Ashing et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2012; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). Cultural influences drive this openness, often because of practices being relative to beliefs about why an illness has come about (e.g., hot and cold imbalances) (Wang et al., 2012; Wong-Kim & Merighi, 2007). Some Asian American women were open to the inclusion of Eastern medicine within their treatments but not in lieu of Western medicine (Tam Ashing et al., 2003; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014; Wong-Kim & Merighi, 2007). Openness to complementary and alternative medicine was most common among more recently resettled Asian immigrants compared to Asian Americans who have lived for generations in the United States (Wong-Kim & Merighi, 2007). Generational Chinese Americans note that navigating information relative to complementary and alternative medicine and Western medicine causes confusion; they emphasize the need for evidence-based education on both treatment options and potential interactions (Wen, Hu, et al., 2014; Wong-Kim & Merighi, 2007).

Psychosocial concerns: Like their non-Hispanic White counterparts, Asian American women report psychosocial concerns related to breast cancer diagnosis and treatment effects. However, how they experience their psychosocial concerns, and how they seek care for them, may be different for Asian American women. Anxiety and depression, including uncertainty and fear of recurrence, are common experiences for cancer survivors (Ashing et al., 2017; Burke et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2012). Stress may result from concerns about employment and insurance coverage, ability to care for their family, physical effects of treatment, body image, and effects on intimate relationships (Le et al., 2017; Tam Ashing et al., 2003; Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al., 2013). Role limitation, emotional well-being, social support, and life stressors are significant predictors of quality of life among women of racial and ethnic minority groups (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2007). Many Asian American women reported internalizing their worries and coping by persisting with household work, such as cooking, cleaning, and child care (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004).

Many Asian American women expressed negative feelings related to body image changes after breast surgery, which affected their self-worth and caused feelings of stigmatization (Tam Ashing et al., 2003). This is expressed more often by women who have undergone a mastectomy compared to lumpectomy, although it is less concerning for older women. Asian American women describe the varied impact of breast cancer treatment on sexual activity, sexual symptoms, and emotional intimacy with partners.

Asian American women report that their anxiety or depression is difficult to deal with, but few seek care from their oncology clinical team (Le et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2013). Some Asian American women express concerns that emotional care is beyond the scope of their oncologist’s responsibility or that their concerns will not be taken seriously (Lee et al., 2013). Indeed, oncology clinicians express concerns that Asian Americans living with breast cancer are not expressing their psychosocial concerns (Lee et al., 2013). Conversely, lack of clear cancer care communication by providers and understanding of treatment effects and surveillance may lead to heightened fear and anxiety in Asian American women with breast cancer (Burke et al., 2016; Tam Ashing et al., 2003).

Social support for Asian American survivors primarily comes from family, including adult children (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2013). Specific to cancer caregiving, spouses are often the primary caregivers for married Asian American women (Lee et al., 2013). Caregivers help with household maintenance, accompany women to appointments, and take part in medical decision-making. Because Asian cultures prioritize family over one’s own needs, women may voice concerns of burdening their family (Le et al., 2017; Tam Ashing et al., 2003). They describe withholding negative emotions from their close caregivers and their diagnosis from friends to avoid burdening them with the knowledge (Lee et al., 2013). Asian immigrant women sometimes report having less social support in the United States than what they would have if they had been in their home country (Lee et al., 2013).

Spirituality: Two studies identified a desire to integrate spiritual care into treatment and after treatment, although not in SCPs explicitly. In a nationwide survey of 119 Asian American Pacific Islanders with cancer, about 52% stated that their emotional needs were unmet and 22% stated that their spiritual needs were unmet (Le et al., 2017). A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina, and White survivors of breast cancer identified the importance of spiritual support after treatment and its lack of availability (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004).

Utilization

Asian American women living with breast cancer reported that utilization of SCPs in survivorship care was low and that SCPs rarely integrated complementary and alternative therapies, although such treatments were generally accepted by Asian American women.

Use of SCPs: Only two studies explicitly addressed SCPs (Burke et al., 2016; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). Although healthcare providers may be a primary source of information about survivorship care, many Asian American women felt they received more information from support groups than providers (Burke et al., 2016). Despite noting that SCPs were used, Burke et al. (2016) found that Asian American women were not satisfied with SCPs because these women felt that they were ill-equipped for life with a cancer diagnosis. Conversations around survivorship care with their healthcare providers, facilitated by written lay language SCP documents, were preferred (Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). To better prepare and care for themselves, Chinese and Filipina women requested information that would assist with self-management of health in relation to side effects, self-care (e.g., diet, nutrition, exercise), and hereditary cancers (Burke et al., 2016). Communicating with providers and being able to understand and use information in the SCP are most important to survivors and their families.

Integration of complementary and alternative therapies: Among the articles that directly addressed SCPs, there was a need for information on diet and exercise and complementary and alternative therapies to be included in SCPs (Burke et al., 2016; Wen, Hu, et al., 2014). In the study by Wen, Hu, et al. (2014), participants recognized that complementary and alternative therapies could not replace Western medicine treatment but desired more information regarding reliable and approved therapies.

Although Ashing-Giwa et al. (2004), Lee et al. (2013), Tam Ashing et al. (2003), and Wang et al. (2012) did not address SCPs directly, they identified the desire for alternative and complementary therapies to be integrated during and after treatment. In a study of Asian American survivors, participants reported that physicians offered minimal information on complementary and alternative medicine, despite Asian American patients relying on both alternative and Western medicine (Tam Ashing et al., 2003). In another study with Chinese immigrant women, a majority of participants preferred to use traditional Chinese medicine and food in their postdiagnosis care. However, participants expressed concern regarding affordability as a barrier (Wang et al., 2012). In an in-depth interview study of four Chinese and five Korean American breast cancer survivors, participants reported a desire for nutrition and diet plans after treatment, expressing that a few of them had had to buy books from their home country in their native language to answer particular questions (Lee et al., 2013).

Barriers in Survivorship Care Delivery

Asian American women with breast cancer reported barriers to survivorship care delivery relative to barriers in language, patient–provider relationships, survivorship education, and systems within health care.

Language barriers: Asian Americans were more likely than Latina Americans (with similar acculturation) to believe that their health was affected by sociocultural factors (Lim et al., 2009). Acculturative stress factors, such as language, were barriers to accessing and navigating survivorship care (Lee et al., 2013; Tam Ashing et al., 2003). Wen, Hu, et al. (2014) reported that differences in cultural communication create barriers to accessing care and engaging with healthcare providers. Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al. (2013) found that Chinese immigrants in the San Francisco Bay Area had few difficulties with communication because of the availability of resources (e.g., interpreters, Chinese physicians, personal English proficiency).

Patient–provider relational barriers: Asian Americans who are more acculturated reported positive patient–provider relationships (Lim et al., 2009). However, other potential communication barriers relative to the patient–provider relationship exist. Lack of trust and a personal relationship with healthcare providers is a barrier across Asian American groups (Lim et al., 2012; Tam Ashing et al., 2003). Lim et al. (2012) noted that Korean Americans reported that attitudes and communication styles are influential and relative to how information is received, whether or not they are stressed by information, or whether or not they will follow the doctor’s recommendations. Chinese Americans perceived that they were more likely to receive support in making decisions than Korean Americans (Lim & Paek, 2013). In addition, Lim and Paek (2013) showed that decisional support might also be more important to Chinese Americans, given that there were implications of higher quality of life in those who received such support. Higher quality patient–provider relationships are predictive of better quality of life in Asian Americans (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2007). Racial concordance may enhance therapeutic relationships between survivors and healthcare providers (Wen, Fang, & Ma, 2014).

Survivorship education barriers: Whether or not rapport is established with healthcare providers, Asian American breast cancer survivors report receiving a lack of guidance for life after diagnosis and treatment beyond medications and scans (Wen, Fang, & Ma, 2014). Transitions from active treatment to surveillance and from oncologist to primary care provider are critical points when survivorship education is needed (Burke et al., 2016). Most Asian American women perceived that comprehensive survivorship education—such as that concerning screening, recurrence, adverse effects and pain, reconstruction, healthy eating and physical activity, and heredity—is integral to delivery of the SCP (Burke et al., 2016). U.S.-born Chinese patients perceived that normalization of distress lessens healthcare providers’ conversations about and initiation of interventions to meet survivorship needs (Wang et al., 2012). However, some healthcare providers perceived that Asian American women were not proactive about their care, particularly those who were less acculturated (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004; Tam Ashing et al., 2003). Gaps in survivorship education may ultimately lead to greater unmet needs.

Systemic healthcare barriers: There is a need to build culturally informed healthcare systems around diverse populations of cancer survivors (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). Understanding that some Asian Americans may have low socioeconomic status and rely on safety-net care (which may be of a lower quality or more overwhelmed with need) is also important to consider (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004). Noted systemic challenges faced also include limited tailoring of SCP content, variable methods of delivery and information relative to tailored resources, nonstandardized follow-up and outcomes, and undifferentiated roles of healthcare providers (Burke et al., 2016). Healthcare providers may also be unaware of culturally appropriate resources to which they can refer Asian American survivors (Lee et al., 2013).

Discussion

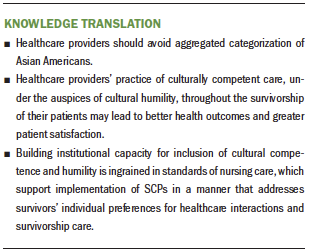

This review provides insight into the preferences concerning, utilization of, and barriers to implementation of survivorship care planning among diverse Asian American women with a breast cancer diagnosis. In addition, this review highlighted similarities and variabilities across these findings. Given that one of the largest issues in research among Asian Americans is the dearth of knowledge surrounding subgroups of Asian American women (Holland & Palaniappan, 2012), there is an impetus to avoid aggregated categorization of Asian American individuals. This review also underscores the importance of healthcare providers practicing culturally competent care, under the auspices of cultural humility, throughout the survivorship of these women to potentially achieve better health outcomes and greater patient satisfaction, as has been seen in other racial and ethnic minority groups of survivors (Lewis-Thames et al., 2020).

Although common needs in survivorship, like psychosocial care and attention to spirituality, were noted (Lewis-Thames et al., 2020), preferences and needs in survivorship care among Asian American women with breast cancer were colored by sociocultural contexts. For example, socioeconomic well-being is a priority in survivorship for all; however, Chinese immigrants report disproportionately lower socioeconomic well-being in comparison to U.S.-born Chinese survivors (Wang, Adams, Tucker-Seeley, et al., 2013). Consequently, building cultural competence toward cultural humility in the management of diverse Asian American individuals with breast cancer during survivorship care is paramount. However, articles in this review describe sentiments revealing that the care received, particularly around the communication of information, is not routinely congruent with their culture. Precipitating conditions for communication barriers in care delivery included acculturative stressors (e.g., language), lack of relationships with healthcare providers, and socioeconomic-driven issues. In terms of language, this review points to the pertinence of recognizing that Asian American women face challenges in regard to health literacy, which may also be compounded by challenges with English literacy for some Asian American women.

The purpose of the SCP is to provide a comprehensive treatment summary and relevant recommendations for surveillance and maintenance of health (Hewitt et al., 2006), and it may be used to reduce patient–provider communication barriers. It is well known that language proficiency affects healthcare outcomes (Lee et al., 2012). Particularly for less-acculturated individuals, the SCP can be another opportunity to gain clarity surrounding their care. A study of Canadian women of Chinese descent identified that survivorship care information should be delivered in the survivor’s native language, removing some of the communication barrier but also providing much needed credible information to consider when partnering with healthcare providers to self-manage survivorship care (Singh-Carlson et al., 2013). Credible information can be used to assist Asian American women with decisions like whether one should seek Western, traditional, or complementary and alternative treatments for curative purposes or adverse treatment effects.

This review also highlighted the scarcity of literature describing the utility of SCPs in this population. The utility of SCPs is vastly unknown because of a lack of studies (American College of Surgeons, 2019). However, findings from this study and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2021) guidelines support their inclusion in survivorship care. Singh-Carlson et al. (2013) found that Asian American survivors also supported the use of SCPs, citing that SCPs would be useful when tailored to survivors’ needs and culture and delivered in a structured format. Rationale for such sentiments may be that SCPs offer an additional credible resource for survivors who might otherwise be inundated with verbal information during care visits. However, there is still no clear consensus on who should deliver the SCP during care. Some may prefer oncology-directed care, whereas others would accept delivery in a general practice (Wallner et al., 2017). Still others might even prefer that a nurse rather than a physician provide the SCP (Singh-Carlson et al., 2013).

This review also highlighted barriers of SCP implementation in this population: language, patient–provider relationship, lack of targeted survivorship education, and the healthcare system. As alluded to in this review, language is one of the largest barriers to the effective delivery and comprehension of treatment-related information in preparation for decision-making. Although compounded by the potential for some Asian American women to experience a language barrier, the patient–provider relationship is integral to better survivorship outcomes (Lee et al., 2012). However, cultural norms of reverence for healthcare provider opinions may pose challenges to fostering conversations about needs and concerns (Wang, Adams, Pasick, et al., 2013). Other structural barriers (e.g., healthcare system navigation, healthcare access, language access), particularly in times of added stresses, as with the COVID-19 pandemic, are amplified. For example, Hmong Americans reported additional challenges with accessing resources that are culturally appropriate (Thorburn et al., 2013), and Chinese immigrants may have difficulty in building rapport with healthcare providers in terms of expressing themselves on telehealth calls (Tsoh et al., 2016). Despite the barriers identified, SCP implementation was seen positively and welcomed by diverse Asian American women in this review.

There were a number of strengths of this review. The search was completed in a systematic manner with clearly delineated inclusion and exclusion criteria that corresponded to the purpose of the study. Limitations of this review included the paucity of studies relative to the topic, few studies with randomized controlled trials, and predominately small sample sizes. Despite these limitations, this review provides valuable information on a growing population of breast cancer survivors.

Implications for Practice

Although SCPs are not mandated by accrediting bodies, there may be benefits of their implementation among Asian American individuals living with breast cancer. Importantly, the delivery of SCPs should be dependent on individual survivorship needs and preferences. Implications for nursing care delivery might entail assessment of health literacy to gauge understanding of information covered through survivorship care planning. The needs of these survivors may also be met if information, both written and verbal, is congruent with the sociocultural contexts of each patient. For example, for patients primarily speaking a language other than the nurse’s primary language, the nurse should engage interpreters when communicating with such patients. The nurse might also make allowances for family members to be included in conversations surrounding survivorship. Rather than focusing on the SCP as a document, the nurse delivering survivorship care uses the SCP as a living template for follow-up of care, addressing the actual and potential effects of a cancer diagnosis on the lives of their patients.

Congruency in implementation of SCPs must also meet individual preferences for healthcare interactions. Such care can be provided only if there is attention given to cultural competence and humility. Building institutional capacity for the inclusion of cultural competence and humility is ingrained in standards of nursing care (Campinha-Bacote, 2019; Marion et al., 2016). Although the change in the American College of Surgeons’ guidelines provides no incentives for providers’ delivery of the SCP as a part of routine follow-up, this review may suggest a need to readdress the guideline change and health policy through advocacy and education with accountability. Further improving the likelihood of delivery of such care may also be facilitated by diversification of the nursing workforce.

Implications for Research

Because there is a paucity of research supporting implementation of SCPs, additional evidence is needed. There are several elements of importance identified in this review that are worthy of consideration. First, the study of disaggregated groups of Asian American women with breast cancer is warranted. Noted variability in cultural aspects like language and social norms can influence how the SCP document and process are designed and delivered. Second, there may be a particular interest in SCP delivery among Asian Americans with a breast cancer diagnosis and its effect on health literacy, given that individuals who are less acculturated and have lower socioeconomic status might also face challenges with comprehension of details provided during the address of survivorship via the SCP. Third, with the rise of telehealth and the preference of many Asian Americans to include family in healthcare decision-making, it remains to be seen how telehealth might improve healthcare providers’ ability to connect with the family to discuss the health care of the patient. Fourth, cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to understand how SCP implementation affects healthcare and health services outcomes. Taken together, there is much work to be done to afford culturally sensitive survivorship care planning for Asian Americans.

Conclusion

This review indicates that preferences and barriers to SCP implementation must be considered to bolster the utility of SCPs. Although not required by accrediting bodies, SCP implementation in the clinical setting may be an asset in Asian American women’s survivorship care. Research is warranted to further explore SCP utility.

About the Author(s)

Timiya S. Nolan, PhD, APRN-CNP, ANP-BC, is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing, Elizabeth Arthur, PhD, APRN-CNP, AOCNP®, is a nurse scientist at the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, Ogechi Nwodim, MSc, is a medical student in the College of Medicine, Amelia Spaulding, BS, is a research assistant, and Jennifer Kue, PhD, is an associate professor in the College of Nursing, all at the Ohio State University in Columbus. Nolan was supported by a National Cancer Institute R03 grant (R03CA245999-01A) and a K08 award (K08CA245208-01), as well as seed funding from the Ohio State University. Nolan and Kue contributed to the conceptualization and design. Spaulding completed the data collection. Nolan, Arthur, and Kue provided analysis. Arthur, Nwodim, and Kue contributed to the manuscript preparation. Nolan can be reached at nolan.261@osu.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted February 2021. Accepted April 29, 2021.)