Communication About Advance Directives and Advance Care Planning in an East Asian Cultural Context: A Systematic Review

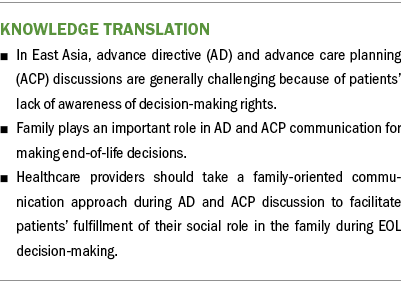

Problem Identification: In East Asian cultural contexts, advance directive (AD) and advance care planning (ACP) discussions are generally challenging given patients’ unawareness of decision-making rights.

Literature Search: Selected databases were searched for articles published from January 2000 to December 2020.

Data Evaluation: 21 studies were included and appraised with Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Systematic Review Checklist.

Synthesis: Five themes emerged: (a) nature of AD and ACP communication, (b) insufficient understanding of the differences between ADs and ACP, (c) late timing of AD and ACP conversations, (d) importance of family participation in AD and ACP communication, and (e) unclear division of responsibilities during end-of-life care.

Implications for Research: Future research should focus on developing a culturally appropriate AD and ACP communication framework.

Jump to a section

Communication between patients and their clinicians provides the opportunity to discuss patients’ expectations of treatment and the issues they are facing. This holds true in advance care planning (ACP), where communication enables individuals with decisional capacity to identify their personal values, to reflect on the meanings and consequences of critical illness scenarios, to define goals and preferences regarding a future medical care plan, and to discuss these items with family members and healthcare professionals (Rietjens et al., 2017). ACP is a process that involves eliciting patients’ wishes about their future medical care and translating those wishes into appropriate care plans for use when patients are no longer able to speak for themselves. To document these decisions, hospitals in many English-speaking countries assist patients to complete an advance directive (AD) form, which is a legal statement about the patient’s substantive directives, or a living will that aligns with treatment preferences in the event the patient becomes incapacitated. The surrogate, who is typically a trusted person to the patient, might be more involved in assisting with decision-making or if the patient becomes incapacitated (Sudore et al., 2017). Epstein and Street (2007) suggested that those who have had an ACP conversation or prepared an AD tend to receive less interventional medical care. This generally leads to a better quality of life near death in patients and less likelihood of bereaved caregivers experiencing major depressive episodes. However, practices that focus mainly on completing legal documents, such as an AD form or do-not-resuscitate orders, were shown to be ineffective means in facilitating end-of-life (EOL) decision-making and fail to improve EOL care (Allison & Sudore, 2013; Heyland et al., 2012). ACP should include communication and open discussion between healthcare providers and the patient’s family to prepare for any future medical crises.

Considering the importance of communication in EOL care, there are protocols and strategies developed to guide clinicians to discuss ACP with patients. For example, A National Framework for Advance Care Directives (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2011) states the goals for policy and practice and promotes the adoption of ACP for recognizing the limits of modern medicine and the role of health-promoting palliative care. Conroy et al. (2009) lists key factors that clinicians need to consider when discussing ACP with patients, such as one’s beliefs and values. Existing frameworks were developed in English-speaking countries, but they may not be applicable in the context of East Asia given the differences in culture between the East and the West. As a result of such cultural differences, the differing perceptions of ACP beliefs could affect patients’ knowledge and willingness to implement ADs and directly affect the engagement level in their own medical care planning.

Typically, in East Asian cultures (e.g., Korea, China, Japan) the following items are true related to death:

• Death is a taboo subject.

• Family plays an important role in medical discussions about the care of a dying patient.

• Patients are expected to fulfill their social role in the family.

For example, Confucianism, one of the traditional East Asian philosophies, influences societies where familial responsibility and harmony are highly valued (Fielding et al., 1998). This makes decision-making a family-centered practice. Family members, and the eldest child particularly, are expected to be heavily involved in making medical decisions in the patient’s care. The sociocultural factors of patients’ communication preferences and their understanding of emotionally challenging topics, such as EOL care and death, play crucial roles in AD and ACP discussions (Labaf et al., 2014; Mystakidou et al., 2004; Pun et al., 2020).

The nature of the AD and ACP communication process (i.e., effective ways to execute discussion among patients, their clinicians, and their families about patient preferences and wishes for future care for when patients lack the capacity to express wishes themselves) has received little attention in previous literature. In the East Asian context, patients generally have not heard of ADs, and few prefer implementing ADs. Most East Asian patients, specifically those of Chinese descent, tend to simply nominate their eldest son or daughter as their proxy (Wang, 2010). This is because filial piety is of value in Chinese culture, and adult children are expected to provide care to their parents as a return for the care they received in early years. Therefore, many patients of advanced age perceive that their children, particularly the eldest, who is typically deemed as having the greatest responsibility in the family, naturally understand the parent’s preference and are capable of decision-making on the patient’s behalf in the final days (Bowman & Singer, 2001; Fan et al., 2019; Kwak & Haley, 2005). However, a Taiwanese study on patient preferences about information disclosure reported that substantial divergences exist between terminally ill patients and their family members regarding the degree to which they were notified of the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis (Tang et al., 2005). Therefore, relying on the eldest child to make EOL decisions for the parent might not always be ideal.

Although there is advocacy in many parts of the world for patients to document their EOL care preferences, such advocacy seems to be absent in the East Asian context. A study with Hong Kong nursing home residents revealed that most participants felt uncomfortable and avoided stating their preferences for EOL care regarding life-sustaining treatment (Chan & Pang, 2007). It was not until 2006 that the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong released a consultation paper on substitute decision-making and ADs that illustrated doctors’ adherence to patients’ AD and EOL preferences. This encouraged local healthcare providers to initiate AD discussions with nursing home residents to ensure that they were familiar with ADs.

There is a dearth of reviews on AD and ACP communication in the context of East Asia. The only available review that documented ACP and AD preferences of Chinese patients from Eastern and Western cultures included 16 articles (Lee et al., 2014). That review identified five major areas related to AD and ACP preferences:

• Factors predicting preferences for AD and ACP

• Chinese-specific considerations related to ACP

• Decision-making in ACP

• Knowledge about ACP and ADs

• Unclear division of responsibilities during EOL care

The findings were in line with those of a study by Hou et al. (2019) in Beijing that explored the knowledge and attitudes of patients with cancer toward ACP. The study reported that a majority of patients had never heard of ACP. Patients who had heard of ACP avoided or refused to engage in conversation about it. The majority also expected that a surrogate would proactively bear all responsibilities on making care decisions when they became unable to do so. These findings highlight the large gap between patients’ knowledge of ACP and their expectations of ACP implementation in the East Asian context in general (Hou et al., 2019).

Previous literature has pointed to the lack of systematic approach in assisting healthcare providers to initiate AD and ACP communication with older adult patients. No effective, culturally appropriate guidelines exist for AD and ACP discussions in the East Asian context, where family plays an important role in such future medical decisions.

Given the paucity of research on AD and ACP communication in the context of Asia, the current systematic review sought to report the scope and nature of AD and ACP communication in East Asian family-centered cultures. Unlike Western culture, in which individualism is emphasized and leads to autonomy that is favorable to the development of ADs, the elements of East Asian culture may hinder truth-telling, discussion of poor prognosis, and conversation about ACP. Therefore, there is a need to identify appropriate communication styles for ACP discussions that take patients’ cultural values into consideration. The aim of this review was to answer the following questions:

• What is the existing research evidence regarding AD and ACP communication with patients in Asia?

• What is the nature of the AD and ACP communication process?

The results elucidate the nature of AD and ACP communication and contribute to future research and policy-making regarding AD and ACP.

Methods

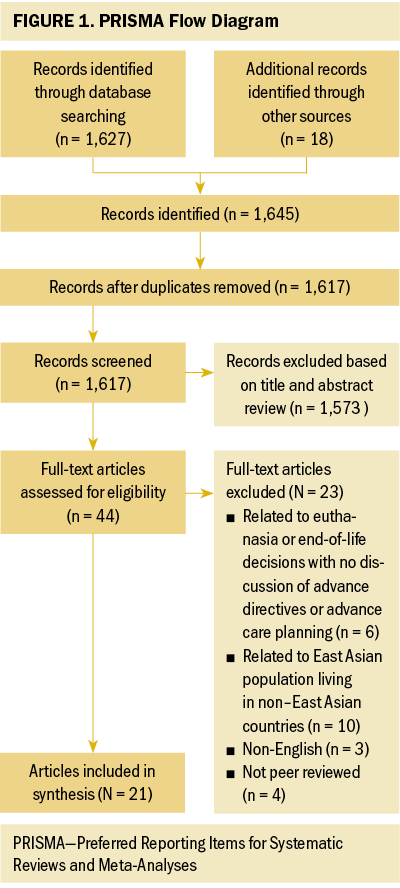

This systematic review used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) model to report studies on AD and ACP communication (see Figure 1). Relevant studies published from January 2000 to December 2020 were included.

Eligibility

PsycINFO®, PubMed®, MEDLINE®, and Health and Medical Collection databases were searched using the keywords advance directive, advance care planning, communication, and Asia. Only peer-reviewed articles that concerned AD and ACP communication with a focus on the East Asian context were considered to be eligible. Exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Articles on euthanasia or EOL decisions with no discussion of ADs or ACP

• Studies conducted in places other than East Asian countries or regions

• Articles concerning East Asian populations living in non–East Asian countries

• Non-English articles

• Non–peer-reviewed articles

Two reviewers cross-checked the initial shortlisted articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria for data extraction and final review.

Data Extraction

To exclude irrelevant articles, the author screened the titles and read the abstract of each article that met the inclusion criteria. If the abstracts were potentially relevant, full text would be reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and subjected to in-depth data extraction. To collate data from the selected articles, objectives, research and study design, results, and discussions were examined and recorded in template form, and were categorized according to their characteristics. The findings of included studies were used to identify themes. Data were extracted and theme identification was performed independently by the author and reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved via team discussion and consultation of another researcher on the team.

Quality Assessment

To ensure the inclusion of high-quality studies, the articles were screened using a series of steps (i.e., keyword selection, title screening, abstract review, and full-text checking) for final data extraction. Disagreements among the author and the two reviewers were evaluated by another researcher in the team; an approach of team discussion was adopted for achieving consensus. Selected studies were appraised with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Systematic Review Checklist (Kryshtafovych et al., 2019). All included studies (N = 21) received a “yes” from the researcher to at least eight assessment items on the CASP checklist. This implies that all articles were of good quality, and no research was discarded in the process. Some examples of the questions included in the CASP checklist were whether the results of the review are valid, how precise the results are, and whether the results can be applied to the local population (Kryshtafovych et al., 2019).

Results

The initial search identified 1,627 eligible articles, with 18 additional records from other sources, resulting a total of 1,645 entries. Screening of the abstracts of those articles led to the exclusion of 1,573 articles based on the exclusion criteria. The remaining 44 studies underwent in-depth full-text screening, which led to the exclusion of an additional 23 articles. Finally, 21 studies were included in this systematic review.

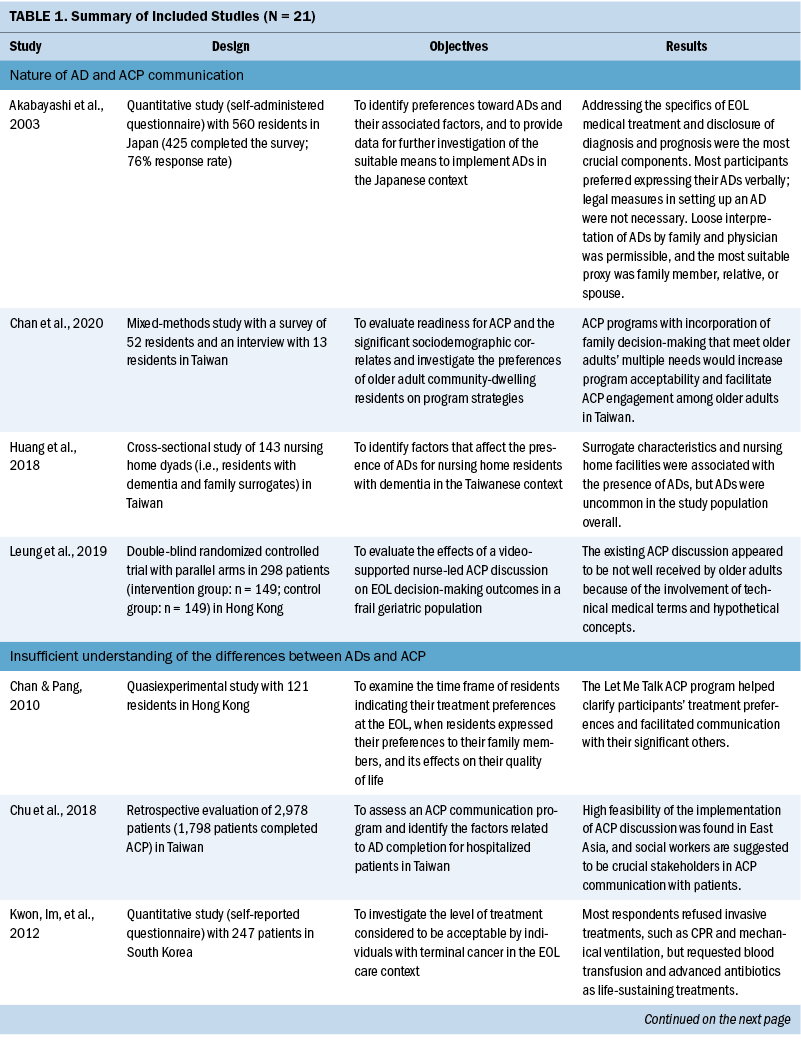

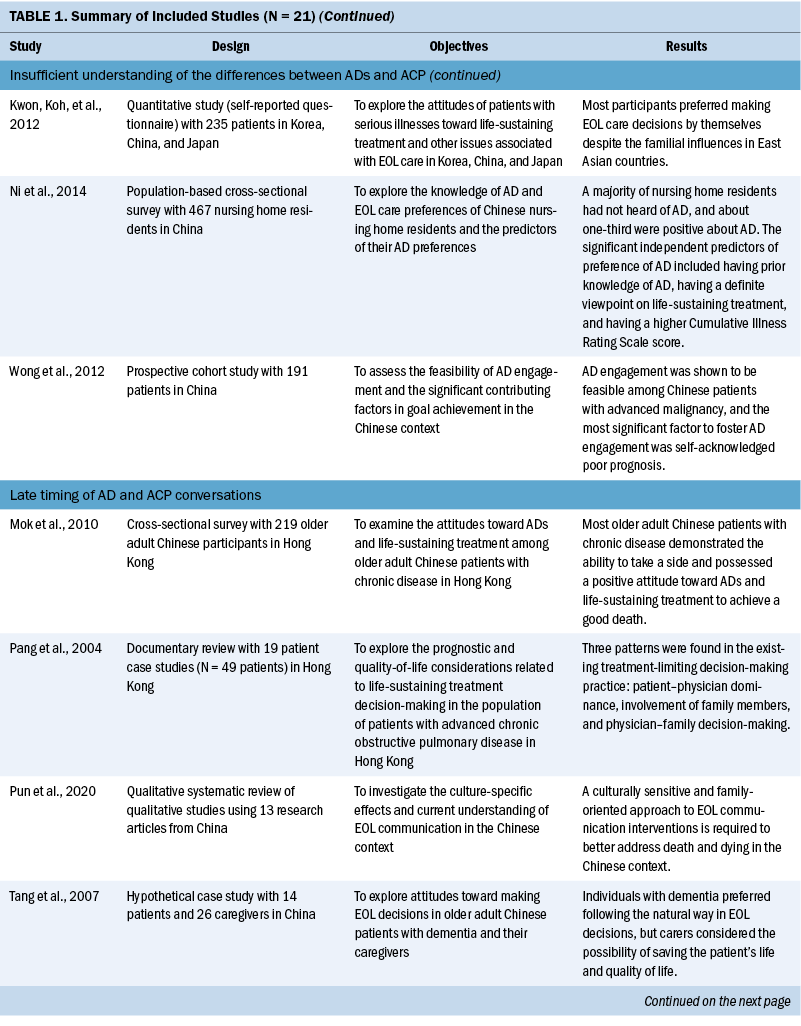

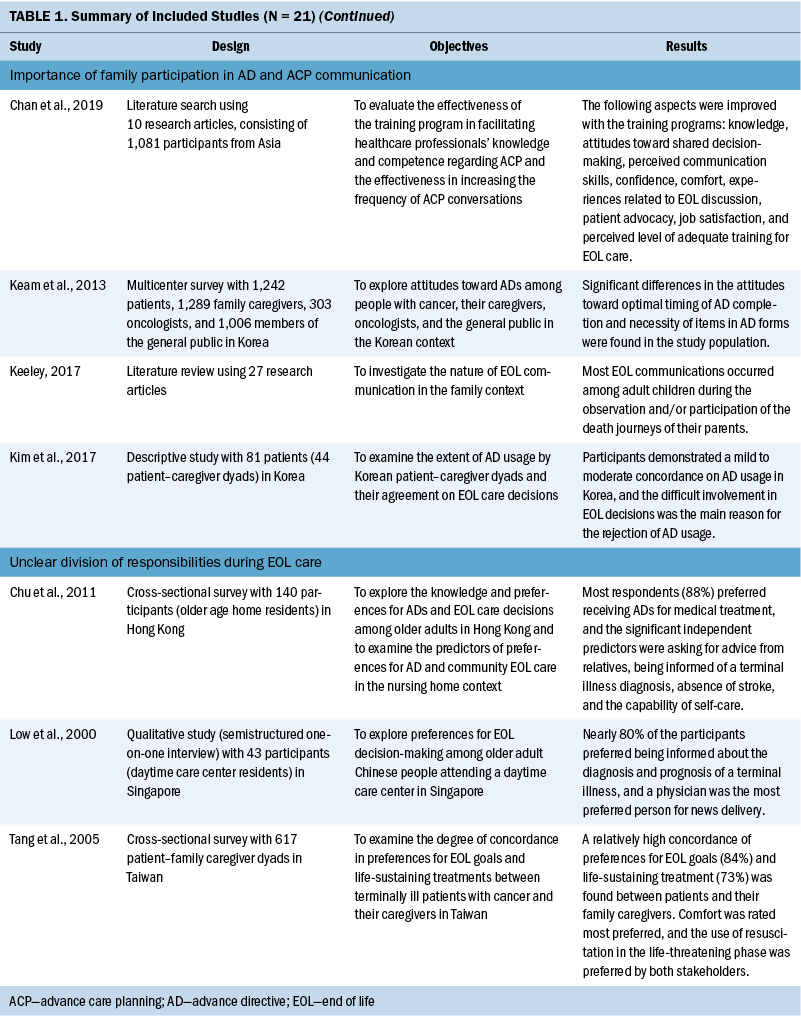

Themes

Rather than using a set of predetermined themes for theme analysis, the author and two researchers coded issues for each included study, which were synthesized into a set of broad common themes. To do this, the team read through each study carefully and gave an initial freecoding to all segments relevant to AD and ACP communication. Then, several rounds of reviews were conducted to compare, sort, and recode for identifying connections among the coded segments and compared analyses from the included studies. In this way, the process promoted a higher level of trustworthiness of the findings. The themes from each included study were identified and coded by the team. Themes were then synthesized into the following set of five overarching, reoccurring themes related to AD and ACP communication in the East Asian context (see Table 1):

• Nature of AD and ACP communication

• Insufficient understanding of the differences between ADs and ACP

• Late timing of AD and ACP conversations

• Importance of family participation in AD and ACP communication

• Unclear division of responsibilities during EOL care

Nature of AD and ACP communication: ACP is a process of communication among a patient, their family members, and healthcare providers to plan the patient’s future medical and personal care in the event of incompetency (Akabayashi et al., 2003). This communication process is designed to assure mentally competent patients that, when the time comes, they will receive EOL care that is consistent with their documented ACP discussion (Chan et al., 2020). The reviewed articles summarized that the key topics to be addressed in ACP communication were disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis and advantages and disadvantages of medical treatment to achieve the provision of quality medical care and EOL care decision-making that aligns with patient preferences. Regarding the means of recording their own AD, the proportions of patients opting for written documentation or oral communication with family members or acquaintances were largely equal, with more than 40% for each (Akabayashi et al., 2003). Although both oral and written approaches may be deemed suitable in implementing ADs, misinterpretation or a lack of direct conveyance to the medical providers tended to occur with verbal ADs. Written ADs, which are legally binding statements that are made while the patient is mentally and physically competent, can specify the patients’ preferences about EOL care and life-sustaining treatments if they lose the capacity to make decisions; therefore, written documentation is encouraged.

Leung et al.’s (2019) research on frail older adults in Hong Kong found an insufficiency in documentation of patient preferences. Huang et al. (2018) noted that the general inadequate regulatory and incentive policies in Asian societies might contribute to the low rate of ADs. However, some predictive factors of presence of ADs included the surrogates being informed of ADs by a healthcare professional, religious affiliation, and implementation of policies in nursing homes. Personal factors might also play a role; the Japanese patients in Akabayashi et al.’s (2003) study reported a neutral stance regarding setting up an AD via legal measures, and loose interpretation of an individual’s AD is widely acceptable. Because of the importance of expression and record of one’s will, encouraging the use of written documentation may be warranted in the East Asian context to promote communication among the patients, family members, and healthcare providers about treatment plan decision-making. It also enables a treatment plan to be developed according to the patient’s wishes, so when family members have to make EOL care decisions on behalf of the patient, their stress and burden can be reduced (Leung et al., 2019).

Insufficient understanding of the differences between ADs and ACP: ACP refers to the communication process about EOL preferences among patients, families, and healthcare providers, and ADs are the documentation of patients’ wills regarding EOL treatment (Chan & Pang, 2010; Chu et al., 2018). The concepts of ADs and ACP are relatively new in East Asian countries, among which Taiwan was the first to implement the Patient Self-Determination Act in 2015 (Chu et al., 2018). A number of places in East Asia, including China and Hong Kong, promote the use of ADs but have not yet established a law regulating the implementation of ADs (Chu et al., 2018). This leads to a general lack of awareness of EOL care plans or of the differences between ADs and ACP in people with East Asian heritage (Ni et al., 2014). According to Kwon, Koh, et al.’s (2012) study using a self-report survey across Korea, China, and Japan, when ADs or ACP are minimally adopted, healthcare providers have to take charge in making significant decisions about the patients’ medical care. Such instances often lead to conflicts between family members and physicians, owing to their inability to agree on the treatment decisions that are in the patient’s best interest (Kwon, Im, et al., 2012).

Patients who lack knowledge of ADs and ACP are often not open to preparing an AD. Contrarily, those who have previously heard of ACP generally welcome the use of ACP for their EOL treatment decision-making. In addition, people who make choices on their own life-sustaining treatments are also more likely to make definite decisions about their future care plans by creating an AD. There is a need for patient education on treatment choices and decisions to raise the acceptance of ADs and ACP and to facilitate EOL care decision-making among East Asian patients (Chan & Pang, 2010; Ni et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2012).

Late timing of AD and ACP conversations: AD and ACP conversations often consist of discussion about bad news. Pun et al.’s (2020) systematic review on Chinese EOL communication revealed that there is typically a delayed initiation of EOL conversations with patients in the Chinese context. Chinese philosophies were found to have heavy influences on East Asian societies, in which patients tended to hold negative attitudes toward engaging in EOL communication. However, practitioners expressed concerns that EOL conversations would pose negative effects on the patient’s emotional well-being, making finding the optimal timing for AD and ACP discussions challenging (Huang et al., 2018; Mok et al., 2010). In cases of people receiving palliative care, the discussion on treatment decisions will become difficult or even impossible if the patient’s health deteriorates unexpectedly, leading to the incapability of participating in AD and ACP conversations. With reference to the Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics Committee (2019), signs such as decline in a patient’s functional status and obvious commencement of the terminal stage are clear indications for the immediate initiation of ACP and creation of an AD, before the patient loses the capability to engage in a conversation (Tang et al., 2007).

Delayed or absent ACP discussions can result in overly interventional life-sustaining treatments, such as CPR, intubation, and mechanical ventilation support. Such treatments are often futile and undesired by patients and family members, because the treatment only lengthens a patient’s life for a few more days and prevents a “good death” (Mok et al., 2010; Pun et al., 2020). An untimely AD and ACP conversation is detrimental not only to the patients, but also to their family members, because it prevents them from engaging in an open conversation regarding the patients’ wishes (Pang et al., 2004) and causes dilemmas and discursive tension as emotions complicate rational discourse (Tang et al., 2007).

Importance of family participation in AD and ACP communication: Collectivism is of value in East Asian cultures, and family-centered medical care environments can be widely seen in countries such as Korea and China; therefore, family participation is a significant aspect in AD and ACP conversations (Kim et al., 2017). Accordingly, healthcare decisions are viewed as group decisions rather than individual decisions, and relative power is considered more crucial than patient autonomy (Chan et al., 2019). A study by Keam et al. (2013) found that, in their study population of people with cancer and their family caregivers in Korea, patients generally showcased favorable attitudes toward ADs despite the traditional belief of death being a taboo topic in many East Asian ideologies. Patients across East Asia generally welcome or prefer to make their EOL decisions and plans together with their family members.

Apart from the traditional values of making joint decisions, involving family members in AD and ACP conversations may also help avoid conflicts from occurring between family and clinicians when making EOL decisions for the patients, particularly at times of a patient’s impending death.

In circumstances where family caregivers are not involved in the communication process, they would ultimately be forced to make decisions on behalf of their dying loved ones without any knowledge of the patient’s will. This creates a possible conflict and competing discourse between what the patient wishes and what the family members want (Keam et al., 2013; Keeley, 2017; Kim et al., 2017). One example is that most families tend to support interventional treatments, such as CPR and artificial ventilation, and patients prefer palliative care that facilitates a good death (Chan et al., 2019). As mentioned, the family element is highly regarded in East Asian societies because of the influences of Confucianism; participation of family members in AD and ACP conversations allows transparency of communication and the opportunities for everyone to express their opinions toward the patient’s EOL care, which promotes joint decision-making within the family.

Unclear division of responsibilities during EOL care: The responsibility of making EOL care decisions is often based on the preferences and best interests of the patient or the family members’ knowledge of the patient’s will (Tang et al., 2005). Given the dynamics of family involvement in the AD and ACP processes, EOL communications may be prone to unclear division of responsibilities among the relevant stakeholders (i.e., the patients, their family caregivers, and clinicians) in the East Asian context. Patients were shown to take a passive role in decision-making and rely on their family members, or occasionally physicians, because many of them are afraid of making decisions that are closely related to their death (Chu et al., 2011). In such cases, the burden of AD and ACP care is shifted to the family caregivers, who become the sole decision-makers during the process, as opposed to their original role of giving supplementary opinions and supporting the patients’ views.

Some patients want their physicians to be the surrogate decision-maker for their health care out of their respect (Chu et al., 2011). East Asians, particularly Chinese people, view medical professionals as figures of authority and often play a passive role during medical consultations because the patients believe that physicians, being professionals, know best and may believe that active participation in decision-making is disrespectful toward physicians (Chu et al., 2011; Low et al., 2000). In these cases, physicians in East Asia may be required to go beyond their normal role as a facilitator and guide in ACP conversations (Tang et al., 2007).

Discussion

This systematic review investigated issues surrounding AD and ACP discussions within an East Asian context in the literature, and summarized AD and ACP communication in five themes. The review identified a general lack of understanding of ADs and ACP in the East Asian community, particularly regarding the nature of and appropriate timing for AD and ACP conversations, and a general insufficiency of knowledge on ADs and ACP or EOL care plans (Chu et al., 2011). These lead to a delay in or nonexistence of AD and ACP conversations, resulting in undesirable occurrences, such as overly interventional life-sustaining treatments or conflicts between family caregivers and clinicians about the best EOL plan for a patient (Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics Committee, 2019; Kwon, Im, et al., 2012).

Another key theme identified was the significance of family members in ACP communication and their positive influence on patients’ quality of life (Kim et al., 2017). Collectivism, as illustrated, greatly influences East Asian societies. Not only are family members heavily involved in making joint decisions on the patient’s health care, but they also play a significant role in supporting the patient. The family support system and care can create a comfortable environment to prepare for the best treatment plans and provide patients with good quality of life near the EOL. In addition, anxiety, psychological stress, and pressure can be alleviated through open discussions (Abbey, 2008; Crain, 1996). In cultures where filial piety is valued, family members, particularly the patients’ adult children, play a paramount role in AD and ACP decisions. Therefore, the burden of treatment decisions mostly falls on the patients’ family, causing the patients themselves to be excluded from the process and constant communication occurring only between healthcare providers and family caregivers (McDarby et al., 2019).

A major issue observed among the included studies was the lack of education on ADs and ACP in East Asian societies, particularly Chinese societies. Although the government has issued consultation papers to encourage health professionals to respect patients’ EOL decisions, there is insufficient education on the significance of EOL decisions to encourage patients to hold AD and ACP conversations (Hou et al., 2019). Education is a significant factor in motivating patients to engage in ACP communication with family members and physicians, because it can influence patients’ treatment choices and increase their AD and ACP acceptance rate (Chan & Pang, 2010; Ni et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2012).

AD and ACP communication is essential for creating an optimal EOL experience for patients who are willing to discuss their AD options with their family members, and advance preparation can help achieve successful AD and ACP conversations. Because healthcare providers are generally well-respected professionals in East Asian cultures and patients place a lot of trust in them, physicians play a significant role in facilitating communication and guiding patients and their family members through the AD and ACP processes (Chan et al., 2019). Although physicians and their medical teams are experts in clinical practice, a patient’s preferences and their needs are equally important for enhancing the quality of their death (Fan et al., 2019). Therefore, it is necessary to tailor the ACP discussion for each patient according to their needs and those of the family instead of adopting a uniform approach (Kwak & Haley, 2005). Typically, because of the heavy influences of Chinese culture across East Asian countries, death and dying are not simply a personal choice but a family-driven decision (Pun et al., 2020). From the viewpoints of traditional values and beliefs among East Asians, a good death is largely determined by the individual’s accomplishment of familial responsibility rather than one’s physical age (Hsu et al., 2009). To most countries in East Asia, the concept of an AD and ACP conversation is relatively new, so more attention should be paid to train medical staff to take patients’ cultural backgrounds and preferences into consideration to prepare for a positive AD and ACP communication experience. Helping patients achieve a good death is the ultimate goal (Fan et al., 2019).

Implications for Nursing

Cultural competence and family influence can significantly affect EOL discussion with patients. This review shows that further research is needed to address the gap in AD and ACP knowledge, as well as the lack of a culturally appropriate AD and ACP communication framework in the East Asian context. For example, Chinese society, as compared to other East Asian countries, has a unique view on death and dying based on its cultural values and beliefs. Death is typically considered as a cultural taboo in traditional Chinese ideology; many Chinese older adults believed that discussing death-related topics would draw them closer to death itself and often avoided issuing ADs (Ho et al., 2013). The current review sheds light on the nature of AD and ACP conversations in East Asia and the factors that must be considered when developing a culturally appropriate communication framework for the promotion of AD and ACP communication among East Asian communities, particularly in the Chinese context.

China has its distinctive cultures that stemmed from ancient Chinese philosophies and religious beliefs, and such values have more or less affected regions of proximity, such as the East Asian region. Despite the typical thinking of death being a component of natural life cycle, most East Asians, particularly Chinese people, possess unique views toward death and dying out of the traditional belief systems. A good death is highly valued by a majority of East Asians, highlighting the cultural and familial dimensions in Chinese culture; therefore, it is a crucial element to be considered in EOL communication. Meanwhile, nursing professionals generally demonstrated incapabilities in starting EOL conversations from a Chinese perspective, particularly showing care and empathy. With their trusting relationships with patients, family members and nurses are the foundation to facilitate a well-rounded AD and ACP communication experience. Given the divergences of culture between East Asia and the West, cultural awareness and competence are of significance in providing quality EOL care in the context of East Asia; nurses should take the perspectives of patients into account and be sensitive and respectful to the patients’ culture to develop a sustainable nurse–patient relationship with mutual trust, to achieve effective communication with patients, and to provide continuity of care. Therefore, being culturally sensitive and adopting a family-oriented approach with Chinese older adult patients are pivotal in nursing practice to better address the unique Chinese conceptions of death and dying.

Engagement of family caregivers at the early stages of EOL conversation can ensure that the patients’ EOL choices are successfully executed. Nurses should equip themselves with suitable training and learning materials for delivering bad news, such as involving family members in diagnosis disclosure if it is the patient’s wish. As such, nurses should possess the competency to gauge patients’ and family members’ willingness to discuss EOL-related issues, so that they could initiate conversations around ACP at the optimal timing and to ensure a good quality of life for patients near their EOL. When necessary, given the dymanics of family involvement in EOL care in the typical context of East Asia, nursing professionals should clarify roles and responsibilities of each party to facilitate prompt and accurate decision-making.

The lack of education and promotion of AD and ACP communication is a serious limitation in this area, and further studies are warranted to develop programs to educate the public about the significance of AD and ACP decisions and promote the acceptance of AD and ACP concepts. It is recommended that AD and ACP communications are individualized according to the needs of the patient and their family to give patients an optimal EOL experience.

Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates the need for further research to address the lack of knowledge about ACP and acceptance of AD and ACP approaches among East Asian patients. It highlights factors that must be considered when developing culturally appropriate communication frameworks and training programs to provide opportunities for AD and ACP discussions in the East Asian setting. It also emphasizes the importance of active involvement of the patient’s family members at the early stages of ACP discussions, when the patient is still cognitively capable of participating in decision-making about their own ACP.

About the Author(s)

Jack K.H. Pun, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the City University of Hong Kong in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. No financial relationships to disclose. Pun can be reached at jack.pun@cityu.edu.hk, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted May 2021. Accepted July 22, 2021.)