The Bereavement Experience for Partners of Patients With Central Nervous System Tumors

Purpose: To describe the experience of caregivers who have lost a partner to a central nervous system (CNS) tumor.

Participants & Setting: 8 bereaved partners of patients with CNS tumors enrolled in a dyadic, behavioral randomized controlled trial at a comprehensive cancer center in the southern United States.

Methodologic Approach: Participants took part in a semistructured qualitative interview to describe the experience of their partner’s death. Descriptive exploratory analysis was used to identify themes emerging from the interviews.

Findings: Themes identified from bereaved participants’ experiences were related to caring for their partner, separating from their partner on patient death, and continuing without their partner following patient death.

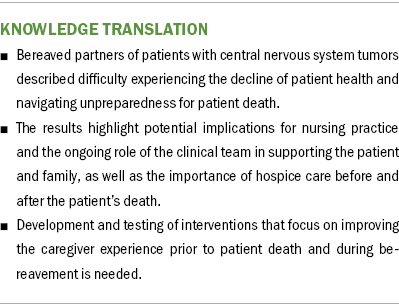

Implications for Nursing: Bereaved partners of patients with CNS tumors described how difficult it was to experience the patient’s health decline and feeling unprepared for the patient’s death, regardless of advance notice. Interventions targeting caregiver distress to improve their experience prior to and following the patient’s death are needed.

Jump to a section

Patients with central nervous system (CNS) tumors experience a unique range of disease- and treatment-related symptoms, as well as an often rapid decline in physical and mental functioning (Maqbool et al., 2016; Piil et al., 2019; Reblin et al., 2017). Patients with CNS tumors experience cognitive declines, neurological and motor deficits, as well as personality changes due to the disease process and cancer treatment, while also experiencing uncertainty related to the disease course and a general poor prognosis (Piil et al., 2019). Caregivers of patients with CNS tumors manage both oncologic and neurologic patient concerns because patients often experience problems with memory, cognitive processing, visual searching, planning and foresight, and attention, along with physical dysfunction related to tumor location and treatment (Piil et al., 2019). Because of the unique presentation of CNS tumors, caregivers of patients with CNS tumors provide patient support and care, which may include coordinating care, monitoring symptoms, administering medications, managing finances, advocating for the patient, and performing physical care tasks without having received formal training (Piil et al., 2019; Sherwood et al., 2006). In the CNS tumor setting, while serving as the patient’s primary caretaker and advocate, caregivers are faced with their own personal challenges associated with the emotional burden of seeing their loved one suffering and anticipating their rapid, further decline and eventual death. Some of these burdens also include the loss of social support and shifts in the relationship, from mutually supportive partners to caregiver and patient (Piil et al., 2019). As the need for caregiving increases with decline of the patient’s condition, caregivers increasingly lose social support, forgoing social activities and friendships and often taking leave or retiring from employment to take care of the patient (Wadhwa et al., 2011). With a rapid progression of disease, patients with CNS tumors often advance quickly from diagnosis to end of life, requiring caregivers to constantly adapt to the patient’s rapidly changing care needs and symptoms, while also feeling powerless to prohibit the eventual patient decline (Reblin et al., 2017; Schubart et al., 2008; Wideheim et al., 2002). Caregivers often neglect their own physical and mental health to prioritize managing changing family responsibilities and caring for the patient, all of which leaves the caregiver at risk for impaired sleep, depression, and anxiety (Piil et al., 2019; Schubart et al., 2008; Wideheim et al., 2002). As the patient’s functioning declines and death becomes imminent, caregiver burden increases (Hricik et al., 2011; Piil et al., 2019; Schubart et al., 2008; Wideheim et al., 2002).

Across cancer settings, caregivers with unmanaged distress before the patient’s death may be at risk for complicated grief and distress during bereavement (Garrido & Prigerson, 2013; Lobb et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2015). When compared to individuals whose partners die from other causes, partners of patients with cancer experience poorer bereavement outcomes, including more depression and greater grief (Caserta et al., 2013). Although death expectedness may mitigate negative outcomes in bereavement, partners of patients with cancer face the patient’s death and their own bereavement already in a state of emotional and physical exhaustion from caregiver distress, depleted of resources needed to cope. This places them at a higher risk for depression, anxiety, complicated grief, and loneliness (Caserta et al., 2013). Managing distress in caregiving partners before the patient’s death may protect partners from complicated grief and distress during bereavement (Garrido & Prigerson, 2013; Lobb et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2015).

Caregivers of patients with CNS tumors are particularly vulnerable to distress and subsequent poor bereavement outcomes given the unique patient presentation (Reblin et al., 2017; Sherwood et al., 2004, 2006). Limited studies have suggested that caregivers of patients with CNS tumors have various unmet needs, such as preparations for the patient’s health decline, social network support, and management of life situations following the patient’s death (Collins et al., 2014; Coolbrandt et al., 2015; Piil et al., 2015). Descriptions of the experience of caring for a patient with a CNS tumor and the bereavement associated with this diagnosis are needed to provide an evidence base for the development and refinement of supportive care interventions. The purpose of this study is to describe the experience of caregivers who have lost a partner with a CNS tumor.

Methodologic Approach

Bereaved partners of patients with CNS tumors enrolled in a dyadic, behavioral randomized controlled trial were invited to participate in a single semistructured qualitative interview to describe their experience surrounding caregiving and their partner’s death. The parent trial tested the feasibility and initial efficacy of a couple-based, mind–body intervention versus a waitlist control group (Milbury et al., 2020). Dyads randomized to the couple-based, mind–body intervention received four 60-minute sessions of mindfulness- and compassion-based meditation training aimed to reduce psychological distress in patients and partners. Dyads randomized to the waitlist control group received standard of care as provided by their oncology care team. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Sample

The parent trial (n = 37 dyads) included patients with a primary or metastatic CNS tumor who underwent any type of cancer treatment within the past month, had a Karnofsky Performance Status score of 80 or higher, and had a spouse or romantic partner who was willing to participate. All patients and partners enrolled in the parent trial were aged 18 years or older, able to speak and read English, able to provide informed consent, and had internet access. Patients were excluded if they regularly participated in psychotherapy or a formal cancer support group, or if they had cognitive deficits that would impede the completion of self-report instruments (as assessed by the clinical team).

Procedures

For this study, partners who were bereaved within 12 months of enrollment in the parent trial were contacted and asked to participate in an additional interview. From March 2019 through August 2019, 11 patients died within 12 months of study enrollment. Researchers were able to contact 8 of the 11 bereaved partners. All agreed to participate in a private, semistructured interview two to nine months after the patient’s death, during which they were asked to describe their experience with caregiving and bereavement. Demographic and clinical information was collected by research staff. The first author (M.W.), who has extensive experience conducting qualitative interviews, conducted telephone calls with participants using an interview guide containing open-ended questions developed by the study team. Interviews began with a general question: “How do you feel now about your partner’s disease and treatment?” Additional probing questions were asked when elaboration was needed, including, “Tell me about your experience of your partner’s disease as it worsened,” “Tell me about your experience of your partner’s death,” “Tell me about your experience since your partner died,” and “What do you see happening in the future?” Interviews lasted 30–45 minutes, and were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were verified against the original audio recording prior to data analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample of bereaved partners. Two researchers with experience in qualitative research (M.W. and M.S.) independently reviewed the transcripts and identified themes using descriptive exploratory techniques (Parse et al., 1985). Researchers then used MAXQDA 2020 to code the transcripts line-by-line. Codes were identified and grouped together into categories and themes (Parse et al., 1985). For bias control and to ensure credibility and dependability in the analysis, two other members of the study team (K.M. and S.C.) reviewed and confirmed the findings. The researchers met to review, discuss, and resolve differences in themes to come to a consensus. Detailed notes of discussions and decisions were kept throughout the analytic process. Participant quotes exemplifying themes were extracted to demonstrate credibility of the findings.

Findings

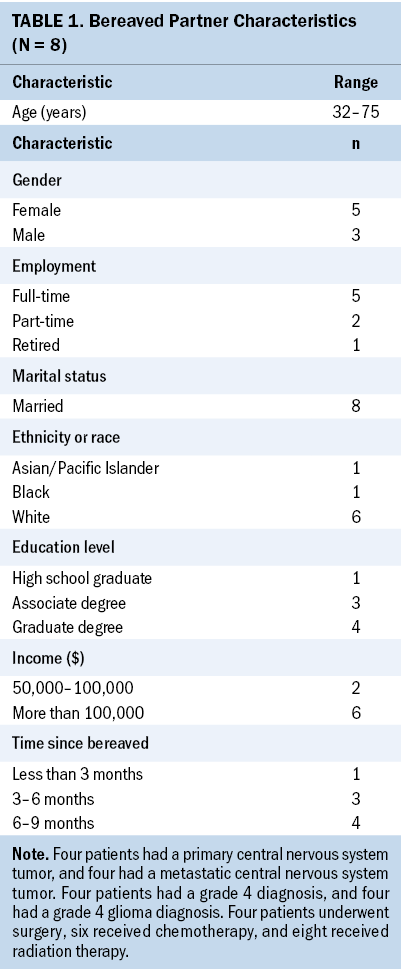

Bereaved partner demographics are summarized in Table 1. Mean partner ages ranged from 32 to 75 years. Of the eight bereaved partners who participated in interviews, five were female, five were employed full-time, and six were non-Hispanic White; all were spousal caregivers. One partner was less than three months bereaved, three partners were between three and six months bereaved, and four partners were between six and nine months bereaved.

Of the patients with CNS tumors, four had a primary CNS tumor, and four had a metastatic CNS tumor. Four patients had a grade 4 diagnosis, and four had a grade 4 glioma diagnosis. Four patients underwent surgery, six received chemotherapy, and eight received radiation therapy.

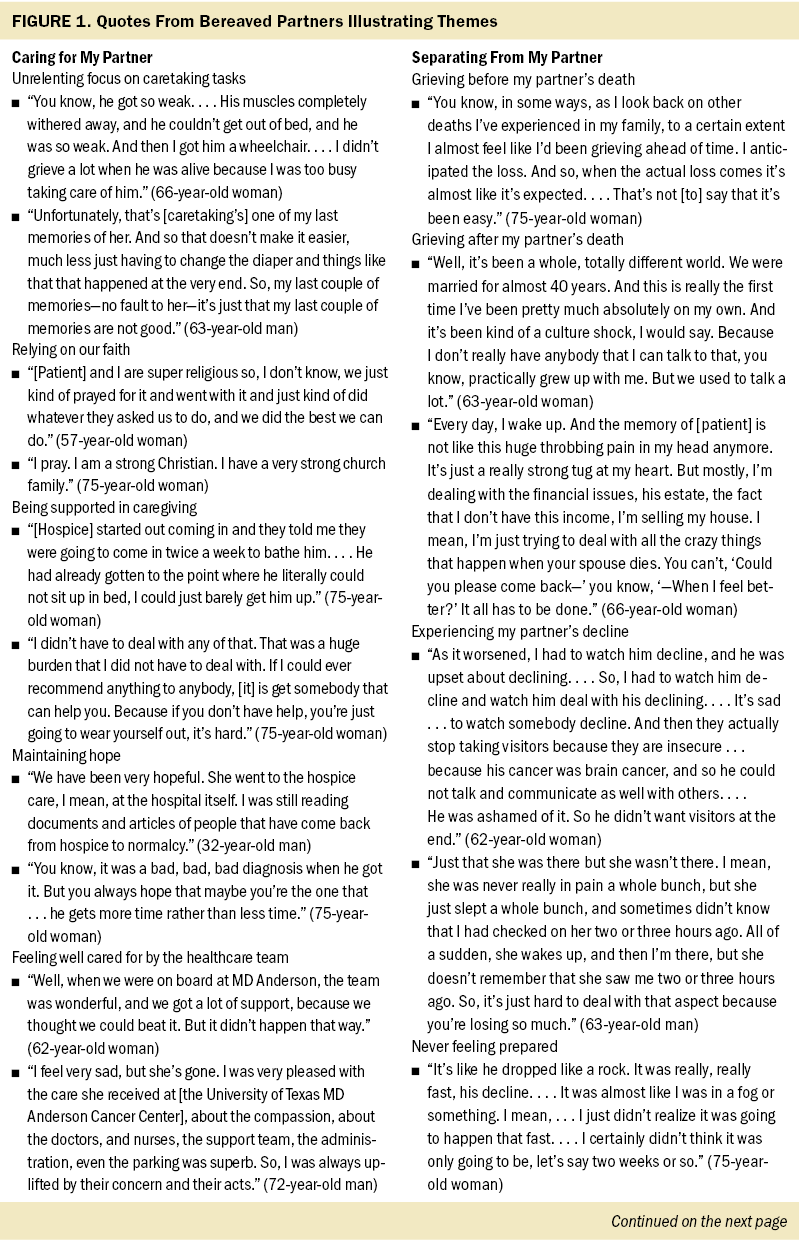

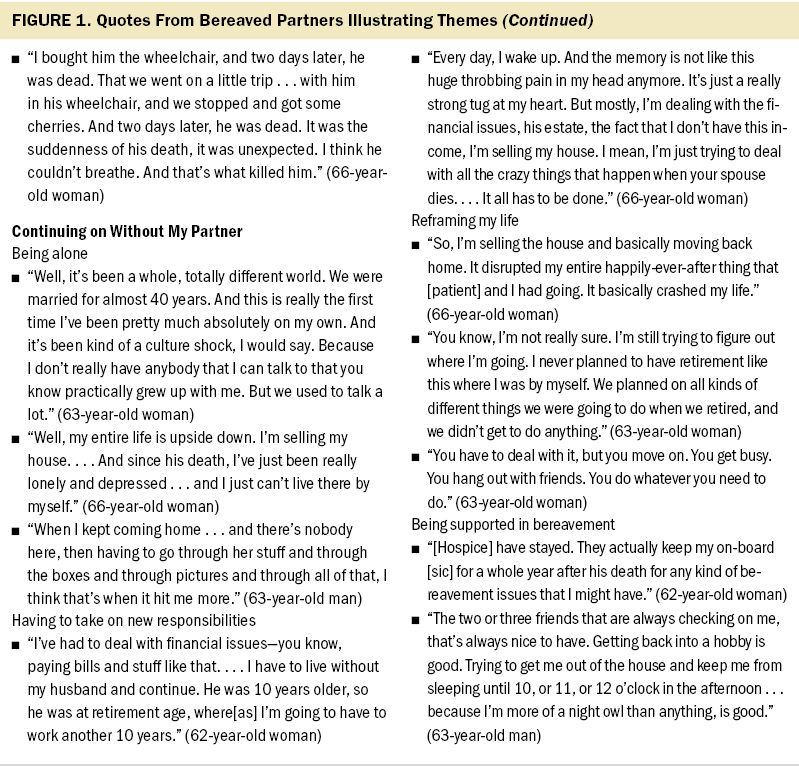

Themes from bereaved partner interviews were organized into three categories: caring for my partner, separating from my partner, and continuing on without my partner. Caring for my partner included the following subthemes: unrelenting focus on caretaking tasks, relying on our faith, being supported in caregiving, maintaining hope, and feeling well cared for by the healthcare team. Separating from my partner included grieving before my partner’s death, grieving after my partner’s death, experiencing my partner’s decline, and never feeling prepared. Subthemes for continuing on without my partner included: being alone, having to take on new responsibilities, reframing my life, and being supported in bereavement. Exact quotes providing examples of each theme are presented in Figure 1.

Intertwined throughout all three themes was the importance of being supported and maintaining hope. Support, which extended from providing medical expertise and helping with day-to-day caretaking tasks to providing an emotional outlet, came from the medical team, hospice, friends and family, and the partners’ faith or spirituality. Partners discussed the need for greater support from the medical team and hospice at the patient’s end of life, so they could better manage caretaking tasks, as well as the importance of ongoing support as they moved into bereavement. Even with support from hospice, partners still found caretaking tasks consuming and sought additional assistance from friends, family members, and private nursing services. Partners expressed regret that their final memories with the patient were often marred by caretaking tasks, as opposed to meaningful goodbyes.

Partners described the difficulty of experiencing the patient’s health decline, particularly when a rapid decline occurred, and feeling unprepared for the patient’s active dying and death. Bereaved partners said it was difficult to observe and manage changes in the patients’ memory, cognition, behavior, and physical functioning. Partners also felt the rapid decline often experienced by patients with primary brain tumors was unexpected and described feeling unprepared to manage both the patient’s physical decline and the emotional experience of losing a loved one so rapidly. Partners underwent multiple, significant life changes following the patient’s death related to figuring out how to manage daily life without their partner and adjusting to being alone. Participants described needing to learn how to manage finances and household tasks, needing to sell and relocate from a shared home, and taking on new employment as they restructured long-term plans. Partners expressed how lonely they felt, how missing the patient was an overwhelming part of their grieving experience, and how they faced an uncertain future. In dealing with loneliness, partners discussed relocating to be closer to family and friends, adjusting to living alone in a previously shared home, and seeking new companionship from family and friends.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies, partners in the current study found caretaking tasks difficult to manage, even with support from hospice, and sought additional assistance from friends, family members, and private nursing services (Piil et al., 2019). In addition, participants in this study described feeling unprepared for the patient’s rapid health decline and eventual death. Bereaved partners in this study described life changes that occurred after the patient’s death, including taking on new responsibilities related to finances, home management, and employment, according to a recent systematic review (Piil et al., 2019). Similar to other studies, partners described loneliness and uncertainty about the future (Collins et al., 2014; Sherwood et al., 2004). Interventions are needed to assist caregivers to adjust to these new life changes.

Limitations

Future research may address this study’s limitations. The findings are limited because of the small sample size and should be verified with larger, more diverse samples and in other caregiver populations. Future research can also focus on first establishing the relationship between various components of the caregiving experience and caregiver outcomes, including bereavement outcomes. In addition, supportive care interventions for partners of patients with CNS tumors are needed and may include education-based interventions for preparing partners for caregiving tasks, the patient’s anticipated rapid decline, and the end of life; mind–body interventions to help caregivers manage distress, depression, sleep, and other caregiver symptoms; and support interventions, such as a provision of respite opportunities for caregivers.

Implications for Nursing

The findings highlight implications for nursing practice and the ongoing role of the clinical team in supporting patients and family caregivers. It also highlights the importance of hospice care before and after the patient’s death. Given that partners of patients with cancer experience poorer bereavement outcomes as compared to partners of patients who die from other causes (Caserta et al., 2013), in addition to the unique CNS tumor setting (Reblin et al., 2017; Sherwood et al., 2004, 2006), more attention is required for the specific needs of caregivers for patients with CNS tumors. In particular, participants described approaching the bereavement period emotionally and physically exhausted from focusing on caretaking tasks, having missed opportunities to connect with the patient. This notion has previously been reported in relation to the patients’ cognitive abilities at the end of life (Coolbrandt et al., 2015), suggesting a need for supportive care interventions designed to assist caregivers in managing caregiver burden, while also creating opportunities to assist the caregivers in connecting with the patient, even as the patient’s cognitive functioning declines.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that additional efforts are needed from the clinical team to prepare partners for the often rapid decline in the patient’s health. Living with the constant uncertainty of the patient’s cancer creates the need to cultivate positive emotions, such as hope, spirituality, and connectedness with loved ones. Interventions, such as mind–body practices that target caregiver distress and focus on communication and adaptive coping, are needed to mitigate partners’ distress and the poor outcomes that persist after the patient’s death. Interventions are also needed to enhance the support provided to partners at the patient’s end of life, when they are struggling to manage caretaking tasks, and into bereavement as they adjust to living alone.

About the Author(s)

Meagan S. Whisenant, PhD, APRN, and Stacey Crane, PhD, RN, CPON®, are assistant professors in the Department of Research, and Mackenzie Stewart, BSN, is a nursing student, all in the Cizik School of Nursing at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; and Kathrin Milbury, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Behavioral Science at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. This research was supported by the Hackett Family Foundation of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K01 AT007559; principal investigator: Kathrin Milbury), and the Hawn Foundation Fund for Education Programs in Pain and Symptom Research. Whisenant, Crane, and Milbury contributed to the conceptualization and design. Whisenant and Milbury completed the data collection. Milbury provided statistical support. All authors provided the analysis and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Whisenant can be reached at meagan.whisenant@uth.tmc.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2021. Accepted August 21, 2021.)