Low-Cost Interventions to Improve Cervical Cancer Screening: An Integrative Review

Problem Identification: Cervical cancer (CC) is a major public health problem in low- and middle-income countries. Although screening can reduce CC incidence, screening programs are difficult to implement in resource-limited countries, making innovative interventions necessary.

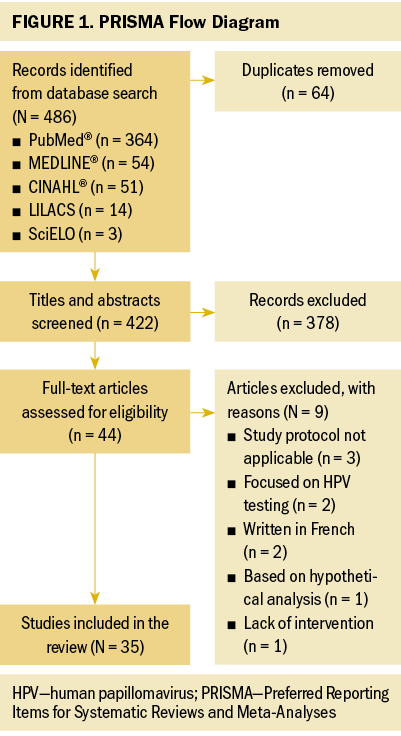

Literature search: PubMed®, MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, LILACS, and SciELO databases were searched for studies published within the past five years that explored interventions to improve CC screening.

Data Evaluation: Of the 486 articles identified, 35 were included in the review. The evidence was summarized, analyzed, and organized by theme.

Synthesis: Several low-cost interventions improved aspects of CC screening, most of which were associated with a significant increase in adherence and uptake. Other interventions led to better baseline knowledge and involvement among patients and healthcare providers and a higher proportion of patients receiving treatment. Screening programs can use single or multiple approaches and match them to the local conditions and available resources.

Implications for Practice: By understanding the various interventions that can mitigate CC incidence, healthcare providers can select the best approach to reach women eligible for CC screening.

Jump to a section

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most frequently diagnosed type of cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in women, with a worldwide estimate of 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths in 2020. This global public health problem primarily affects low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where about 90% of cases occur (Sung et al., 2021). During the 73rd World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) established the 90-70-90 targets within the scope of the global strategy for CC elimination. The 90-70-90 targets recommend that 90% of girls be vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV) at age 15 years, 70% of women be screened with a high-performance test at ages 35 and 45 years, and 90% of women identified to have CC be treated, with the goal of reducing the incidence of CC to less than 4 cases per 100,000 women within the 21st century (WHO, 2020).

Effective screening programs can decrease CC mortality rates (Jansen et al., 2020). High-income countries have successfully controlled CC through sophisticated population-based screening policies (Vale, Teixeira, et al., 2021); however, LMICs lack robust resources to quickly fund such programs and typically have fragile healthcare systems and fewer skilled technicians and equipment. As a result, CC incidence rates in LMICs are much higher than those in high-income countries (Gossa & Fetters, 2020).

The structure of a screening program is usually undervalued. Sometimes analyses focus on the performance of diagnostic tests, a critical component of screening. However, analyses of how the cancer screening program is organized, how its methods are implemented, how equitable access is, and how well CC is controlled are also important (Vale, Teixeira, et al., 2021). A contributing factor to effective CC screening programs is adequate uptake within the target population (Paulauskiene et al., 2019). Regardless of the diagnostic test used for screening, the participation of eligible patients at regular intervals is necessary for success (Tsoa et al., 2017). Evidence shows that compared with opportunistic approaches, well-organized population-based screening that invites the target population generates better results and is more effective (Arbyn et al., 2010; Ferroni et al., 2012). In opportunistic screening, uptake depends on the initiative of the individual woman or a provider because the target population is not systematically invited (Arbyn et al., 2010; Paulauskiene et al., 2019).

Interventions, such as invitation letters, education, telephone calls, and text messages, have all been shown to improve CC screening (Albrow et al., 2014; Huff et al., 2017; Kiran et al., 2018; Naz et al., 2018). A combination of low-cost methods might increase adherence in eligible populations. Interventions of increasing complexity and cost may then be used to encourage resistant individuals to participant in CC screening (Firmino-Machado et al., 2019). Combining interventions is highly relevant, not only in LMICs where resources are limited, but also in countries with organized CC screening with low uptake. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to synthesize low-cost interventions used to organize or improve CC screening. The findings can provide direction and recommendations, particularly for LMICs where most CC cases occur.

Methods

Search Strategy

This integrative review was based on the methods described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) and guided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework (Moher et al., 2009). The stages of the process were as follows: identification of the problem, definition of the literature search strategy, data selection, data extraction and analysis, and synthesis of the main findings. PubMed®, MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, LILACS, and SciELO databases were searched using the following terms and their equivalents in Portuguese: uterine cervical neoplasms and mass screening and organization and strateg* or intervention.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies written in Portuguese or English published between 2016 and 2021 with an exclusive focus on interventions to organize or improve CC screening were included. The search was limited to five years to include current studies about cost-effective CC screening interventions. This time frame also considered the WHO (2021) guideline for screening and treatment of cervical precancer lesions for CC prevention, which recommends using HPV testing as the primary screening method rather than visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) or cytology.

Commentaries, expert opinions, protocols, dissertations, reviews, and studies that used a hypothetical model, such as projections and population estimates, were excluded. Studies that used HPV testing for screening were also excluded because of the high cost.

Data Collection and Evaluation

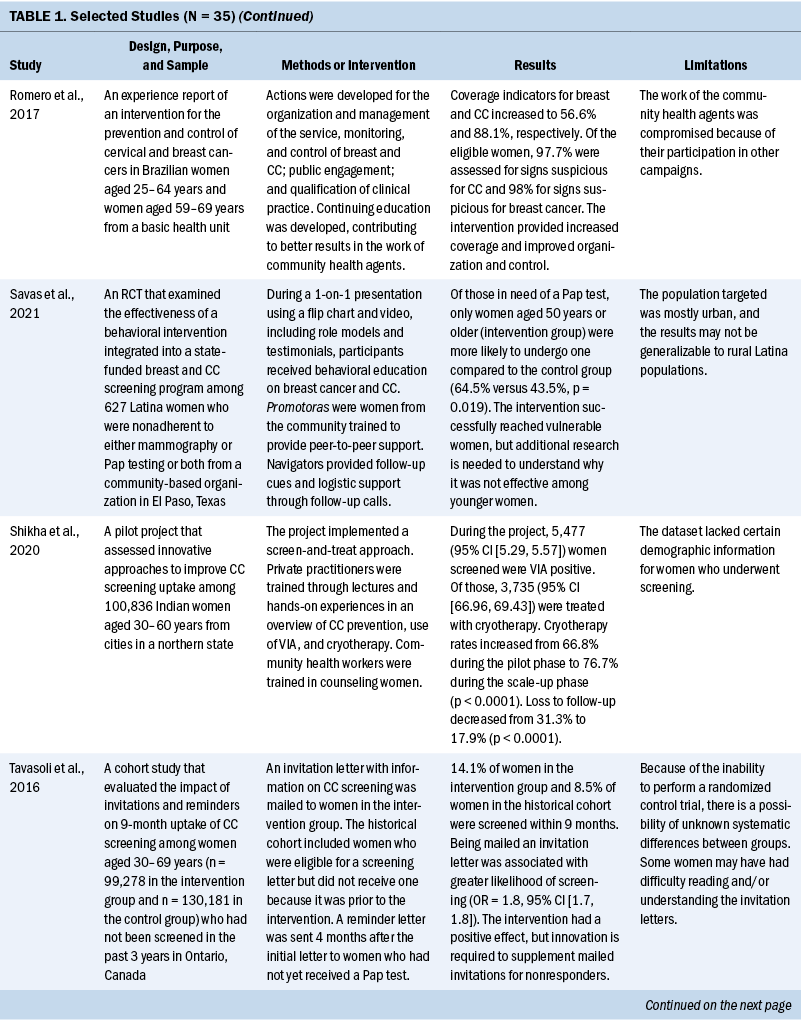

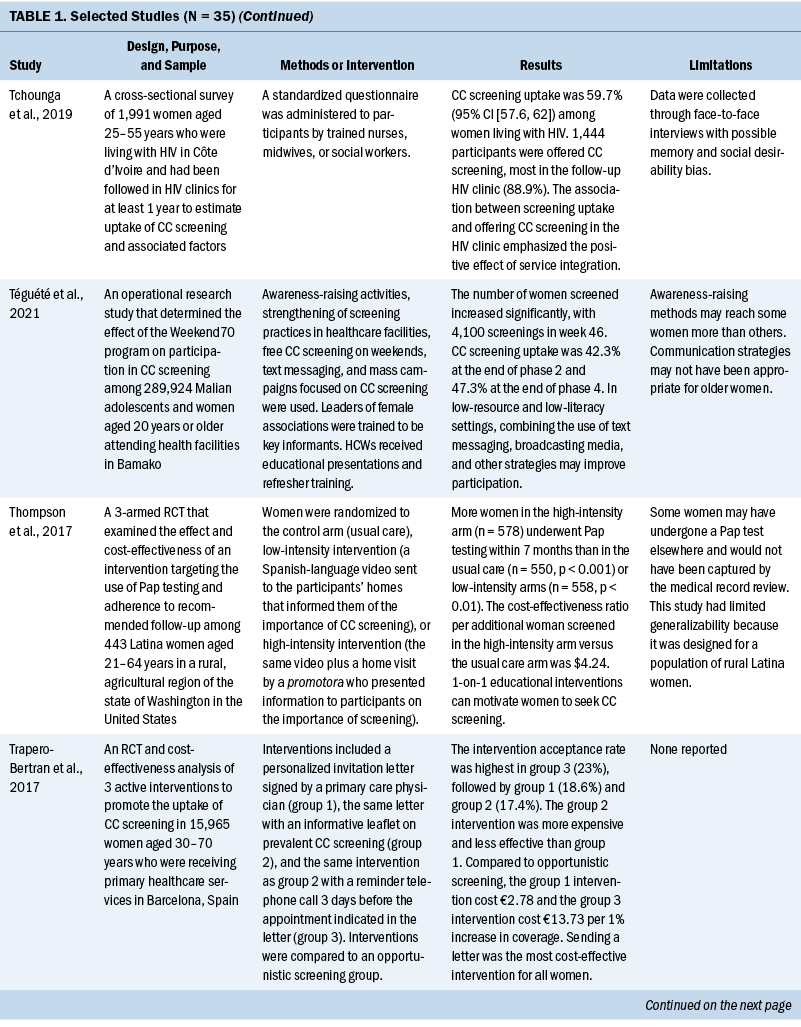

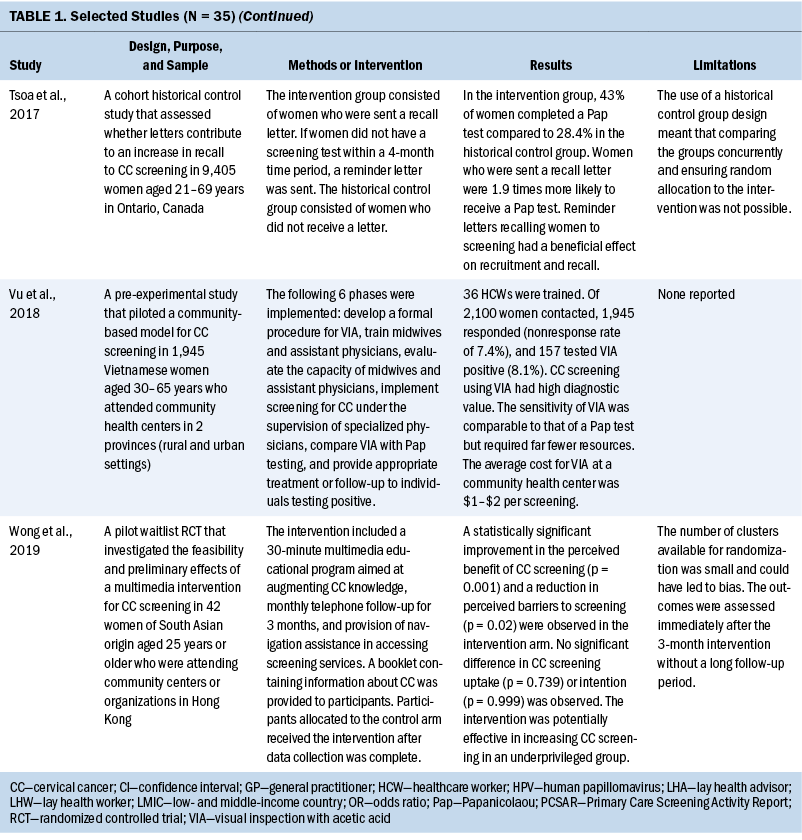

The initial search returned 486 records (see Figure 1). After eliminating duplicates, titles and abstracts from the remaining 422 articles were reviewed. Of the 44 full-text articles screened for eligibility, 35 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis. The 35 studies were individually reviewed to extract data concerning purpose and design, population and sample, methods or intervention, main results, and limitations. Findings were grouped thematically and compiled for presentation.

Results

Study Characteristics and Target Populations

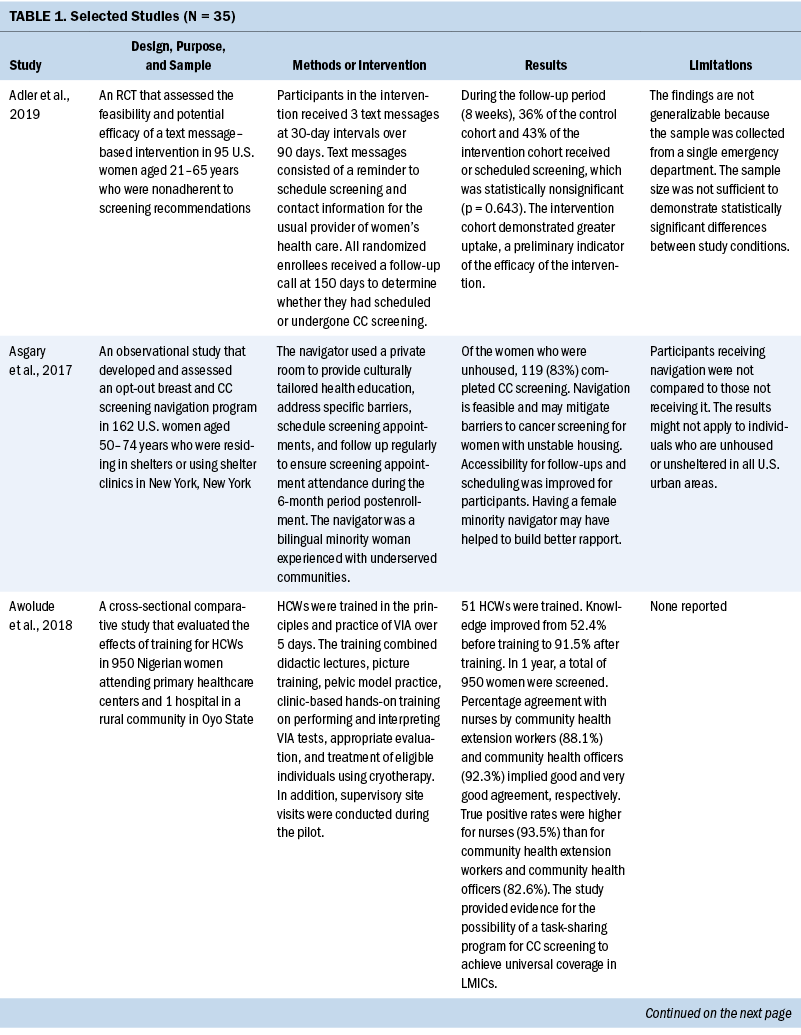

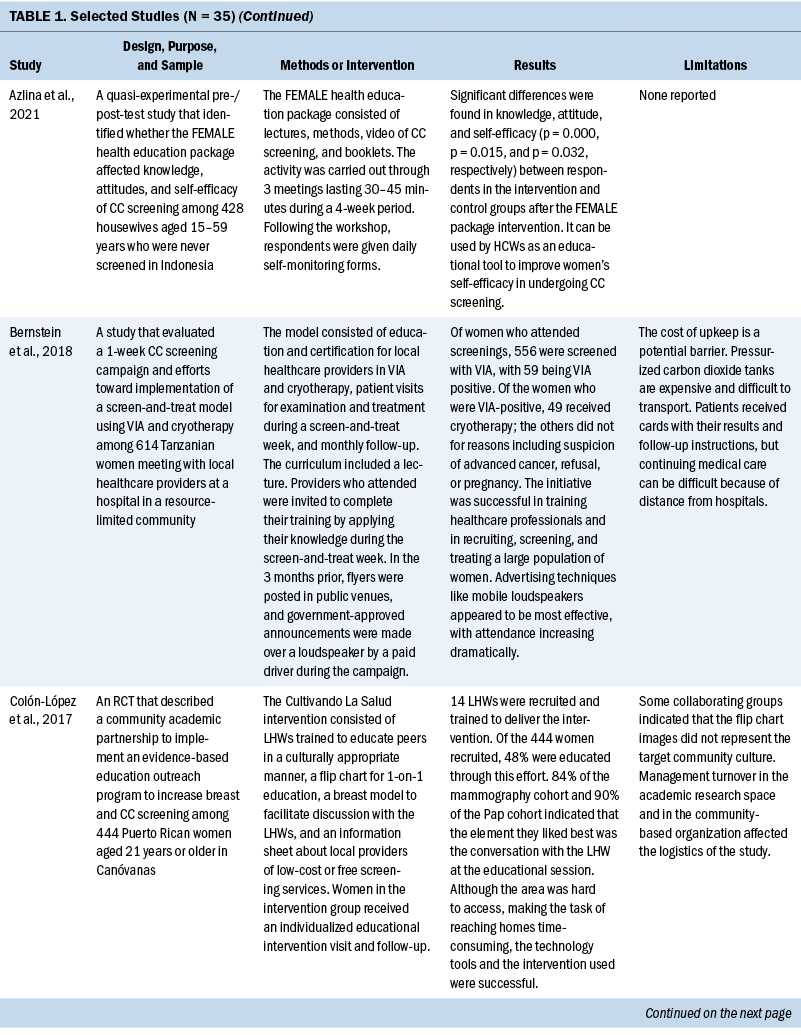

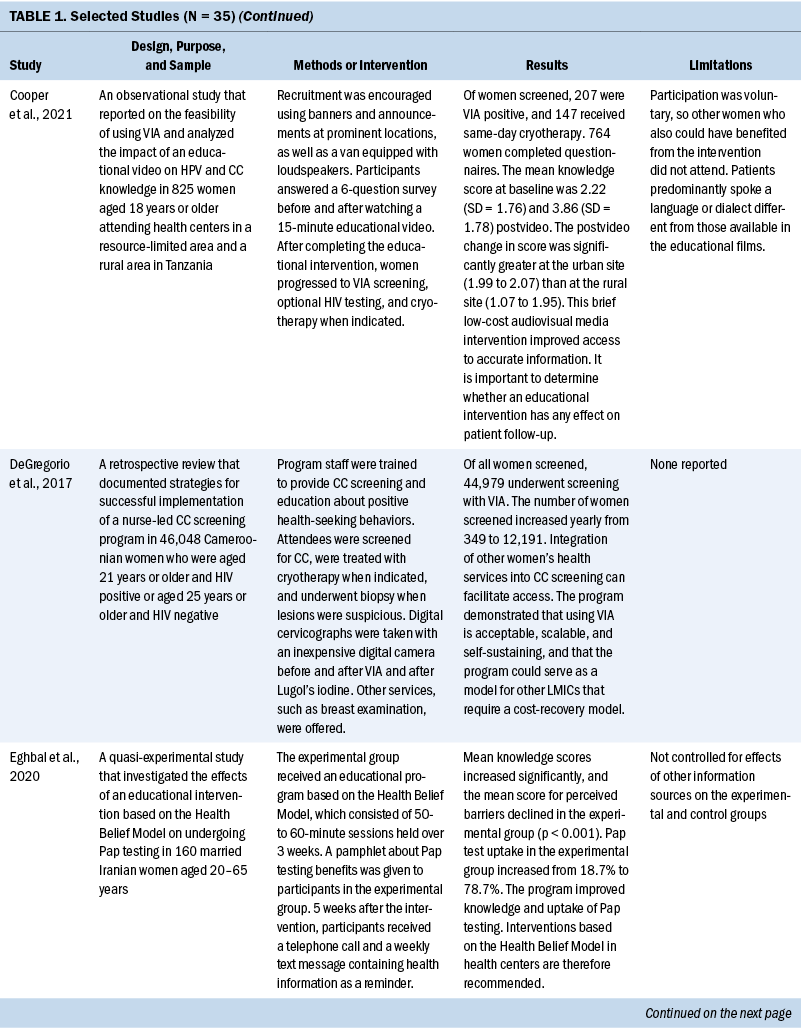

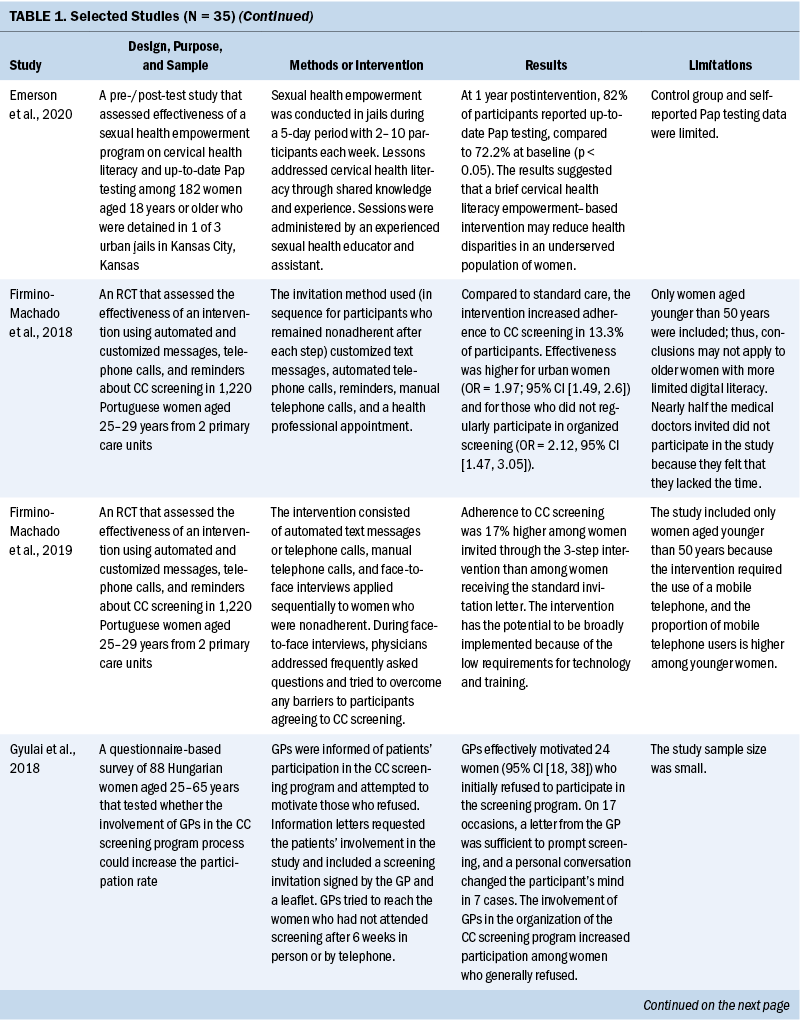

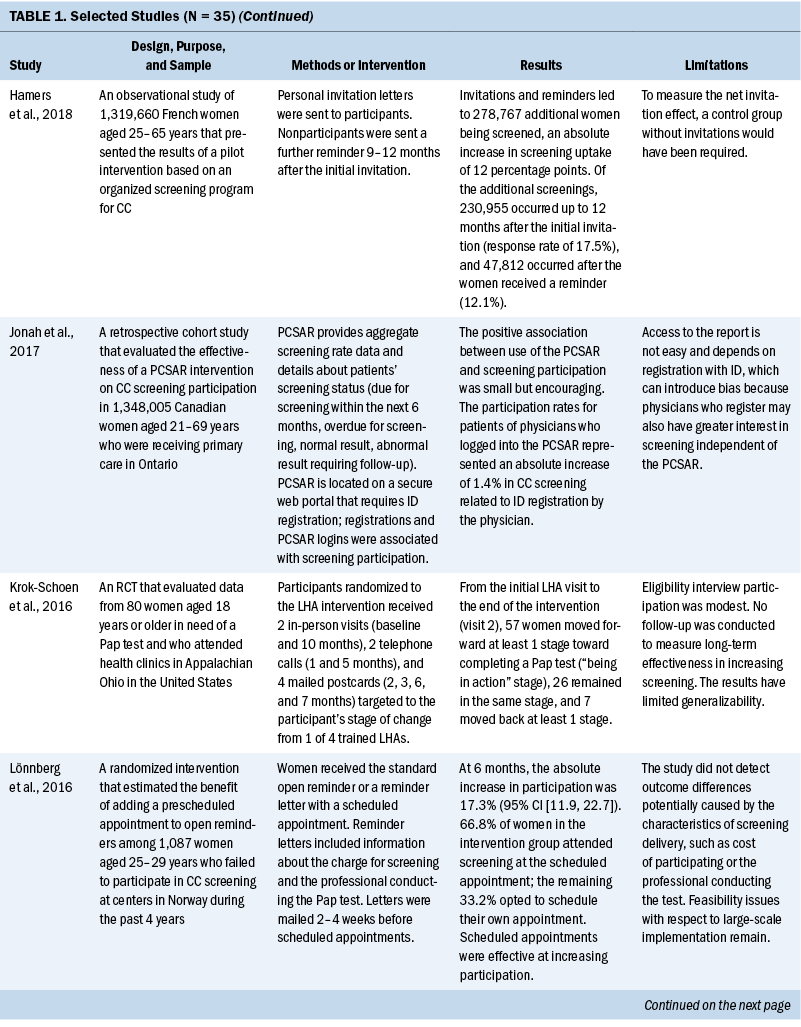

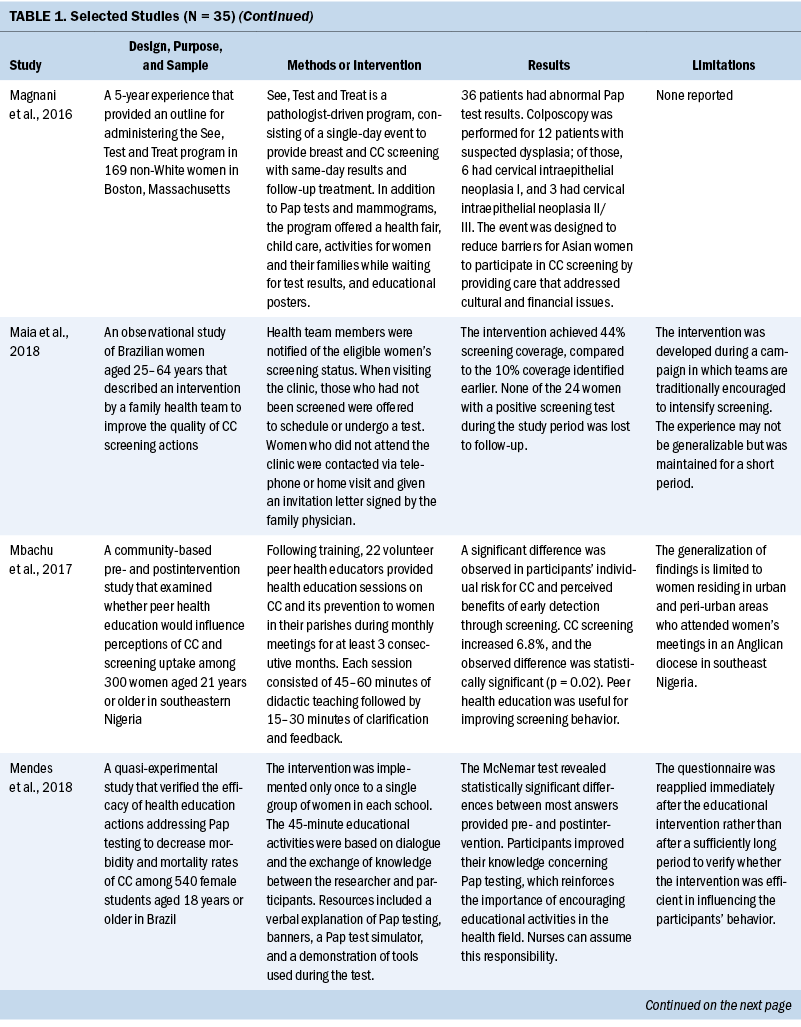

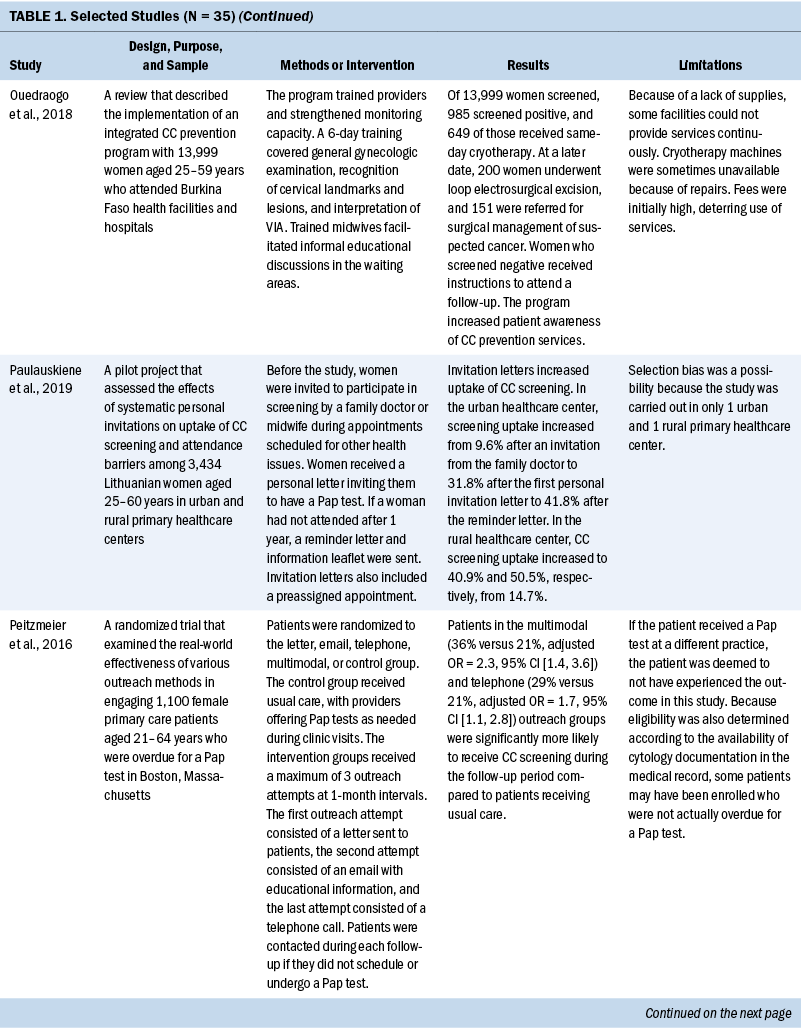

Thirty-five studies were selected (see Table 1). Most studies were conducted in North America (n = 11), Africa (n = 8), and Europe (n = 7); the remaining studies took place in Latin America (n = 4), Asia (n = 4), and the Middle East (n = 1). Among the 21 countries represented, the United States was the locale for 8 studies (Adler et al., 2019; Asgary et al., 2017; Emerson et al., 2020; Krok-Schoen et al., 2016; Magnani et al., 2016; Peitzmeier et al., 2016; Savas et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2017). LMICs were the focus of 15 studies.

Few studies (n = 5) were conducted in both urban and rural communities (Cooper et al., 2021; Firmino-Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Paulauskiene et al., 2019; Vu et al., 2018); only three were conducted in rural areas (Awolude et al., 2018; Eghbal et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2017) and three in resource-limited or high service need places (Bernstein et al., 2018; Colón-López et al., 2017; Cooper et al., 2021). Health centers were the most common study site (n = 18). Specific sites described included an emergency department (Adler et al., 2019), shelters and shelter clinics (Asgary et al., 2017), hospitals (Bernstein et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018), schools (Mendes et al., 2018), jails (Emerson et al., 2020), an HIV clinic (Tchounga et al., 2019), and community organizations and centers (Savas et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2019). The study designs were diverse, with most studies being randomized controlled or clinical trials (Adler et al., 2019; Colón-López et al., 2017; Firmino-Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Krok-Schoen et al., 2016; Savas et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2017; Tapero-Bertran et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2019).

Across all studies, a total of 3,390,237 women were approached. The target age range was 15–70 years. Most studies prioritized engaging women who had not undergone CC screening in the preceding 2.9–3.5 years or greater (n = 15). Other studies focused on specific populations, such as women who were homeless (Asgary et al., 2017), HIV positive (DeGregorio et al., 2017; Tchounga et al., 2019), in jail (Emerson et al., 2020), or members of ethnic minority groups (Magnani et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2019).

Interventions

CC screening methods used in the studies included Papanicolaou (Pap) tests and VIA. Pap tests were the most common method used (n = 23). Some interventions were contextualized to breast cancer screening (Asgary et al., 2017; Colón-López et al., 2017; Jonah et al., 2017; Magnani et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2017; Savas et al., 2021). In these studies, delivering interventions to improve CC and breast cancer screening simultaneously were successful. The interventions consisted of providing free cancer screening (Magnani et al., 2016), opt-out patient navigation (Asgary et al., 2017), education outreach (Colón-López et al., 2017), electronic reporting as an audit and feedback tool (Jonah et al., 2017), organization and management of the healthcare service (Romero et al., 2017), and the use of lay healthcare workers (HCWs) (Savas et al., 2021).

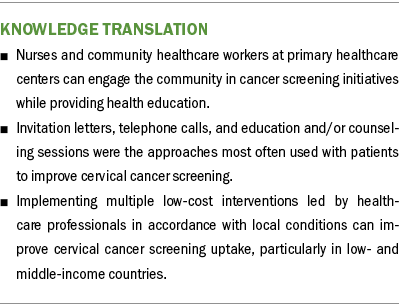

Various screening interventions were described, and most studies used multiple methods simultaneously. Therefore, the interventions were categorized by the group for which they were intended (e.g., patients, HCWs, service) and by content (see Table 2). Invitation letters, telephone calls, and education/counseling sessions were the approaches most used with patients to improve CC screening. For HCWs, specific training and the use of navigators, lay HCWs, promotoras (lay Hispanic or Latino community members), and key informants were frequently used. Regarding the screening service itself, scheduling appointments and offering screen-and-treat days were the main interventions described. Integrating CC screening with other health services for women, such as HIV clinics, was shown to be an effective way of enabling women to address additional healthcare needs (DeGregorio et al., 2017; Tchounga et al., 2019).

Outcomes and Costs

All included studies obtained positive outcomes of various types or amplitudes. Some authors described an absolute improvement on screening uptake ranging from 1.4% to 17.3%, with a mean absolute improvement of 11.2%, when comparing intervention and control groups (Adler et al., 2019; Firmino-Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Jonah et al., 2017; Lönnberg et al., 2016). Other studies that compared intervention and control groups obtained better CC screening rates among experimental populations: 36% versus 21% (Peitzmeier et al., 2016), 14.1% versus 8.5% (Tavasoli et al., 2016), 53.4% versus 34% (Thompson et al., 2017), 43% versus 28.4% (Tsoa et al., 2017), and 64.5% versus 43.5% (Savas et al., 2021).

An increase in uptake was also observed in studies using an experimental group when comparing pre- and postintervention data. Hamers et al. (2018) showed an increase in uptake of 12%, and Mbachu et al. (2017) found an increase of 6.8%. In other studies, the rates improved as follows: 10% to 44% (Maia et al., 2018), 9.6% to 41% in urban areas and 14.7% to 50.5% in rural areas (Paulauskiene et al., 2019), 18.7% to 78.7% (Eghbal et al., 2020), 72.2% to 82% (Emerson et al., 2020), and 42.3% to 47.3% (Téguété et al., 2021). The mean difference in uptake across all experimental studies was 24.4%. Other outcomes included positive rates of acceptance to complete screening among participants in the intervention without a comparison group or baseline data (Asgary et al., 2017; DeGregorio et al., 2017; Magnani et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2017), improvement in baseline knowledge and perceived benefits of CC screening for patients and healthcare providers (Awolude et al., 2018; Azlina et al., 2021; Cooper et al., 2021; Mendes et al., 2018; Vu et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2019), high proportion of treatment with cryotherapy (Bernstein et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018; Shikha et al., 2020), acceptance of an educational approach (Colón-López et al., 2017), and a greater chance of eligible women participating in screening because of improvements in motivation or state of change for Pap testing (Gyulai et al., 2018; Krok-Schoen et al., 2016).

Some studies emphasized the low cost of the screening method or intervention implemented. VIA was described as a simple, low-cost option that required limited technology and training, which is an advantage in low-resource settings (Awolude et al., 2018; Bernstein et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018; Shikha et al., 2020; Vu et al., 2018). Text messages, automated telephone calls, audiovisual media, and good practices at healthcare centers (e.g., implementing actions to organize CC screening, actively seeking patients in need of screening) were described as low-cost accessible interventions (Adler et al., 2019; Cooper et al., 2021; Firmino-Machado et al., 2018, 2019; Maia et al., 2018). Organized screening was cited as cost-effective (Paulauskiene et al., 2019). Lay HCWs played a role in informing their community about reduced-cost or free CC screening services (Colón-López et al., 2017; Krok-Schoen et al., 2016). Thompson et al. (2017) found that a promotora intervention conducted by a lay health worker had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per additional woman screened of $4.24.

Two studies described fees for VIA between $1 and $3 (Téguété et al., 2021; Vu et al., 2018). Firmino-Machado et al. (2018) expected that their intervention based on automated text messaging and telephone calls costs as much as €0.10 per woman invited at the national level in Portugal. The most cost-effective intervention identified was based on an invitation letter costing €2.78 per 1% increase in screening uptake (Trapero-Bertran et al., 2017). Reduced-fee or cost-free services were observed to improve participation among women (Ouedraogo et al., 2018; Téguété et al., 2021). DeGregorio et al. (2017) found that charging a small fee for service was acceptable and important to making a screening program self-sustaining. In addition, Maia et al. (2018) suggested that low-cost Pap tests might not be sufficient because improving contact among women and HCWs would also be necessary to increase participation.

Discussion

Characteristics of Interventions

The diversity of the interventions suggests a large range of possibilities to improve CC screening and reflects a need to implement specific or a combination of strategies to the target population based on available resources and demographic characteristics. Invitation letters were the most common intervention described and were associated with an increase in screening uptake, particularly letters that contained notifications of scheduled appointments (Gyulai et al., 2018; Hamers et al., 2018; Lönnberg et al., 2016; Paulauskiene et al., 2019; Peitzmeier et al., 2016; Tavasoli et al., 2016; Trapero-Bertran et al., 2017; Tsoa et al., 2017). Conducting education and counseling sessions with the eligible population was also well described and associated with improvements in knowledge about CC, increases in screening uptake, and more women agreeing to complete the screening (Azlina et al., 2021; DeGregorio et al., 2017; Eghbal et al., 2020; Emerson et al., 2020; Mbachu et al., 2017; Mendes et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018).

According to Staley et al. (2021), invitation letters and educational interventions are the most effective methods for increasing the absolute uptake of CC screening. Antinyan et al. (2021) found that invitation letters substantially increased CC screening participation in LMICs. Although these studies reinforce this review’s findings about the success of invitation letters, it is not feasible to assume that this type of intervention is the most effective in all conditions. All interventions provided some advantage to CC screening, with the target population benefiting in different ways independently of the type of intervention used.

Using mobile telephones to invite people to CC screening has the potential to spread knowledge and incentivize participation in LMICs. In a systematic review of eight studies, Zhang et al. (2020) found that mobile technologies, particularly telephone reminders or messages, contributed to an increase in Pap test uptake. These findings reinforce the results of studies conducted by Adler et al. (2019) and Firmino-Machado et al. (2018, 2019), which found that text messaging and automated telephone calls improved adherence to screening.

Providers can influence patients’ clinical behaviors and attitudes toward CC screening (O’Connor et al., 2021). Some studies engaged healthcare providers with educational training and access to information about patients’ screening status to help them become more active in promoting CC screening. Such actions were successful in improving knowledge among HCWs and patients, motivating eligible women, and increasing screening uptake in many studies (Awolude et al., 2018; Bernstein et al., 2018; DeGregorio et al., 2017; Gyulai et al., 2018; Jonah et al., 2017; Maia et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018; Romero et al., 2017; Shikha et al., 2020; Téguété et al., 2021; Vu et al., 2018).

Community HCWs play a role in CC screening education, outreach, and awareness activities. Shikha et al. (2020) approached local community HCWs and trained them to counsel women, and Wong et al. (2019) led a multimedia outreach intervention for ethnically underrepresented individuals. Other studies relying on cultural legitimacy trained navigators, lay HCWs, promotoras, and key informants to improve CC screening rates through one-on-one education and promotion of screening awareness (Asgary et al., 2017; Colón-López et al., 2017; Krok-Schoen et al., 2016; Savas et al., 2021; Téguété et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2017). These types of HCWs carry cultural legitimacy, trustworthiness, and acceptability for their communities, and they appear feasible and acceptable in LMICs (O’Donovan et al., 2019).

Several interventions that provided education and counseling sessions for patients succeeded in improving baseline knowledge about CC, which is essential to increasing screening uptake (Azlina et al., 2021; DeGregorio et al., 2017; Eghbal et al., 2020; Emerson et al., 2020; Mbachu et al., 2017; Mendes et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018). Based on the effectiveness of education and counseling in screening uptake, healthcare professionals—including nurses and community HCWs—are integral in leading and performing CC prevention interventions.

Vulnerable Populations

When analyzing inequities in CC, about one half of cases occur in women who have never been screened. Many of those women are poor, live in rural areas, and have limited access to HCWs and infrastructure (Zug et al., 2014). Compared to women living in urban areas, women living in rural areas experience a 13% higher mortality rate (Blake et al., 2017). However, few studies in this review described interventions approaching vulnerable populations of women. Eghbal et al. (2020) demonstrated an improvement in Pap testing rates and CC knowledge after an educational intervention for women living in rural areas. A personal invitation letter was found to significantly increase CC screening uptake more so in rural regions than in urban regions (Paulauskiene et al., 2019). An educational video intervention was associated with a greater change in knowledge scores of women in urban areas than women in rural areas (Cooper et al., 2021). Interventions may not result in the same outcomes in all populations. Rural populations face transportation challenges, ill-equipped health facilities, lack of information, and fewer highly trained HCWs, all of which need to be considered when choosing an intervention (Ndejjo et al., 2016). In addition, HCWs must be trained to promote culturally competent patient–provider communication (Fuzzell et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2008).

Women who are ethnically diverse, marginalized, underserved, part of sex and gender minorities, or immigrants are also vulnerable to disparities in screening. The included studies described solutions, such as mobile screening by community HCWs, education sessions, and patient navigators or promotoras, which could potentially improve adherence to screening and follow-up (Asgary et al., 2017; Emerson et al., 2020; Magnani et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2019). In a study by Asgary et al. (2017), opt-out patient navigation was effective in mitigating barriers to cancer screening among unhoused women. The See, Test and Treat program was designed to reduce barriers for ethnic populations by providing care that addresses cultural and financial issues (Magnani et al., 2016). Wong et al. (2019) suggested that a multimedia intervention led by community HCWs was crucial to enhancing CC screening beliefs for a group of underprivileged South Asian women. A randomized controlled trial to increase CC screening among Latina women in rural areas concluded that one-on-one education provided by a promotora motivates women to seek screening (Thompson et al., 2017). Lastly, Emerson et al. (2020) found that cervical health literacy empowerment delivered to women during a jail detention decreased health disparities. These studies highlighted the range of possible interventions that can be applied to decrease health disparities in underserved patient populations. Given the expertise of healthcare providers, particularly nurses and community HCWs, they are essential in selecting, planning, and conducting the best intervention according to the target population.

CC Screening Settings in LMICs

The highest rates of CC mortality are observed in Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia (Gossa & Fetters, 2020; Sung et al., 2021). However, fewer than half of the studies included in this review were conducted in LMICs (Awolude et al., 2018; Bernstein et al., 2018; Colón-López et al., 2017; Cooper et al., 2021; DeGregorio et al., 2017; Eghbal et al., 2020; Maia et al., 2018; Mbachu et al., 2017; Mendes et al., 2018; Ouedraogo et al., 2018; Romero et al., 2017; Shikha et al., 2020; Tchounga et al., 2019; Téguété et al., 2021; Vu et al., 2018). In these studies, the main outcomes demonstrated after the interventions were improvements in technical knowledge among healthcare providers, high acceptance rates for VIA screening, an increase in baseline knowledge about CC among eligible women, and greater screening uptake.

Screening programs vary between low-resource and high-income areas. In most high-income countries, Pap tests, which require a well-funded healthcare system, are offered as the main screening method. Although HPV testing is recommended by the WHO because of its better sensitivity compared to cytology and VIA, the cost and infrastructure requirements can make widespread implementation difficult (Vale, Silva, et al., 2021). VIA is more feasible in LMICs and has been implemented as an alternative to cytology because it is a low-cost screening technology. VIA does not require laboratory analysis, and trained nonphysician clinicians can perform it in clinics, producing immediate results (Huchko et al., 2015; Sohn, 2020). Among the 15 studies that were conducted in LMICs, 9 described VIA as the preferred screening method.

Studies exploring CC screening in LMICS are important for proposing alternative strategies to improve screening uptake because resources for CC prevention are limited in these countries. In addition, HPV testing is rarely offered. Social and cultural factors, such as a lack of awareness and knowledge about preventive services, limited accessibility, socioeconomic status, and cultural and religious beliefs, also influence the use of screening programs (Chidyaonga-Maseko et al., 2015). However, independently of the type of screening method, CC screening effectiveness can improve by increasing examination coverage, which can be done through the organization of the healthcare services.

Limitations

Of the 35 studies included, only 9 were randomized controlled or clinical trials, which limited the quality of the evidence. The remaining 26 studies used mixed-methods, experimental, or pre-/postintervention or questionnaire-based designs, or were pilot studies, retrospective reviews, or cross-sectional observations. Most studies described some limitations, most commonly an inability to generalize the outcomes, biases in participant selection, small sample sizes, and availability of medical records. More trials are needed to understand how to approach underrepresented populations and evaluate long-term and secondary outcomes, particularly in LMICs where fewer studies have been conducted. In addition, the study was limited by its focus on studies published during a five-year period and the choice to exclude interventions focused on HPV testing.

Implications for Practice

The interventions described in the selected studies were diverse, and the synthesized evidence is valuable for healthcare providers and decision-makers in improving CC screening uptake. Adherence to CC screening depends on many factors (e.g., culture-related behavior, service availability, social and economic status), and healthcare providers play a complex role. In addition to choosing a method to identify cancer or precancerous lesions, defining the screening method can motivate eligible women to participate. Nurses, physicians, and community HCWs comprise an interprofessional team that is responsible for planning and implementing the intervention that is most relevant to local conditions. Nurses and community HCWs at primary healthcare centers can build relationships and engage with the community in cancer screening initiatives while providing health education. They can also influence patients to adopt healthy behaviors by applying the strategies from some of the interventions described. Helping healthcare providers to understand population demands is crucial to the design of more effective interventions and efforts to overcome barriers to screening, particularly in LMICs with limited resources. The findings of this review, which provided examples of interventions that successfully improved CC screening, can be used to guide future health practices.

Conclusion

This integrative review synthesized data from low-cost interventions to improve CC screening. Most studies achieved positive outcomes, including increases in adherence and uptake, improvements in baseline knowledge for patients and healthcare providers and in the best use of healthcare staff, and delivery of treatment to a high proportion of patients with a positive screen result. CC screening program assessments are complex and depend on local conditions. Screening test performance is easily defined in terms of specificity or sensitivity, but early cancer detection cannot be offered until the logistics of screening are defined. Any approach must be adapted to the local cultural and socioeconomic settings and available resources, particularly in LMICs, where programs are often underfunded. Financial implications of CC screening should be investigated, and adequate funding and services for women who need specialist management are needed. Implementing multiple low-cost interventions and involving healthcare providers and the community seem to be the best approaches to improving CC screening uptake.

About the Authors

Giselle A.S. Rezende, BPharm, is a master’s student of biotechnology in the Center for Research in Biological Sciences, Mariana T. Rezende, PhD, is a technological and industrial development scholarship student level B in the Department of Clinical Analysis, and Cláudia M. Carneiro, PhD, is a titular research professor in the Department of Clinical Analysis in the School of Pharmacy, all at the Federal University of Ouro Preto in Brazil. This research was funded, in part, by the Brazilian Parliamentary Amendment (No. 39160010), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, the Minas Gerais Research Funding Foundation, the Dean of Research, Graduate Studies, and Innovation, and the Dean of Extension and Culture at the Federal University of Ouro Preto. G. Rezende contributed to the conceptualization and design and completed the data collection. All authors provided the analysis and contributed to the manuscript preparation. G. Rezende can be reached at giselle.rezende@aluno.ufop.edu.br, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted December 2021. Accepted May 19, 2022.)

References

Adler, D., Abar, B., Wood, N., & Bonham, A. (2019). An intervention to increase uptake of cervical cancer screening among emergency department patients: Results of a randomized pilot study. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 57(6), 836–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.07.021

Albrow, R., Blomberg, K., Kitchener, H., Brabin, L., Patnick, J., Tishelman, C., . . . Widmark, C. (2014). Interventions to improve cervical cancer screening uptake amongst young women: A systematic review. Acta Oncologica, 53(4), 445–451.

Antinyan, A., Bertoni, M., & Corazzini, L. (2021). Cervical cancer screening invitations in low and middle income countries: Evidence from Armenia. Social Science and Medicine, 273, 113739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113739

Arbyn, M., Anttila, A., Jordan, J., Ronco, G., Schenck, U., Segnan, N., . . . von Karsa, L. (2010). European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition—Summary document. Annals of Oncology, 21(3), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp471

Asgary, R., Naderi, R., & Wisnivesky, J. (2017). Opt-out patient navigation to improve breast and cervical cancer screening among homeless women. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(9), 999–1003. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6066

Awolude, O.A., Oyerinde, S.O., & Akinyemi, J.O. (2018). Screen and triage by community extension workers to facilitate screen and treat: Task-sharing strategy to achieve universal coverage for cervical cancer screening in Nigeria. Journal of Global Oncology, 4, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.18.00023

Azlina, F.A., Setyowati, S., & Budiati, T. (2021). Female health education package enhances knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy of housewives in cervical cancer screening. Enfermería Clínica, 31, S215–S219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2020.12.025

Bernstein, M., Hari, A., Aggarwal, S., Lee, D., Farfel, A., Patel, P., . . . Ries, M. (2018). Implementation of a human papillomavirus screen-and-treat model in Mwanza, Tanzania: Training local healthcare workers for sustainable impact. International Health, 10(3), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihy014

Blake, K.D., Moss, J.L., Gaysynsky, A., Srinivasan, S., & Croyle, R.T. (2017). Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: An analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 26(7), 992–997. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0092

Chidyaonga-Maseko, F., Chirwa, M.L., & Muula, A.S. (2015). Underutilization of cervical cancer prevention services in low and middle income countries: A review of contributing factors. Pan African Medical Journal, 21, 231.

Colón-López, V., González, D., Vélez, C., Fernández-Espada, N., Feldman-Soler, A., Ayala-Escobar, K., . . . Fernández, M.E. (2017). Community–academic partnership to implement a breast and cervical cancer screening education program in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 36(4), 191–197.

Cooper, E.C., Maher, J.A., Naaseh, A., Crawford, E.W., Chinn, J.O., Runge, A.S., . . . Tewari, K.S. (2021). Implementation of human papillomavirus video education for women participating in mass cervical cancer screening in Tanzania. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 224(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.018

DeGregorio, G., Manga, S., Kiyang, E., Manjuh, F., Bradford, L., Cholli, P., . . . Ogembo, J.G. (2017). Implementing a fee-for-service cervical cancer screening and treatment program in Cameroon: Challenges and opportunities. Oncologist, 22(7), 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0383

Eghbal, S.B., Karimy, M., Kasmaei, P., Roshan, Z.A., Valipour, R., & Attari, S.M. (2020). Evaluating the effect of an educational program on increasing cervical cancer screening behavior among rural women in Guilan, Iran. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01020-7

Emerson, A.M., Smith, S., Lee, J., Kelly, P.J., & Ramaswamy, M. (2020). Effectiveness of a Kansas City, jail-based intervention to improve cervical health literacy and screening, one-year post-intervention. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(1), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117119863714

Ferroni, E., Camilloni, L., Jimenez, B., Furnari, G., Borgia, P., Guasticchi, G., & Rossi, P.G. (2012). How to increase uptake in oncologic screening: A systematic review of studies comparing population-based screening programs and spontaneous access. Preventive Medicine, 55(6), 587–596.

Firmino-Machado, J., Varela, S., Mendes, R., Moreira, A., & Lunet, N. (2018). Stepwise strategy to improve cervical cancer screening adherence (SCAN-Cervical Cancer)—Automated text messages, phone calls and reminders: Population based randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine, 114, 123–133.

Firmino-Machado, J., Varela, S., Mendes, R., Moreira, A., & Lunet, N. (2019). A 3-step intervention to improve adherence to cervical cancer screening: The SCAN randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine, 123, 250–261.

Fuzzell, L.N., Perkins, R.B., Christy, S.M., Lake, P.W., & Vadaparampil, S.T. (2021). Cervical cancer screening in the United States: Challenges and potential solutions for underscreened groups. Preventive Medicine, 144, 106400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106400

Gossa, W., & Fetters, M.D. (2020). How should cervical cancer prevention be improved in LMICs? AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(2), E126–E134. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2020.126

Gyulai, A., Nagy, A., Pataki, V., Tonté, D., Ádány, R., & Vokó, Z. (2018). General practitioners can increase participation in cervical cancer screening—A model program in Hungary. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0755-0

Hamers, F.F., Duport, N., & Beltzer, N. (2018). Population-based organized cervical cancer screening pilot program in France. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 27(5), 486–492.

Huf, S., King, D., Kerrison, R., Chadborn, T., Richmond, A., Cunningham, D., . . . Darzi, A. (2017). Behavioural text message reminders to improve participation in cervical screening: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 390, S46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32981-1

Jansen, E.E.L., Zielonke, N., Gini, A., Anttila, A., Segnan, N., Vokó, Z., . . . de Kok, I.M.C.M. (2020). Effect of organised cervical cancer screening on cervical cancer mortality in Europe: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer, 127, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.12.013

Huchko, M.J., Sneden, J., Zakaras, J.M., Smith-McCune, K., Sawaya, G., Maloba, M., . . . Cohen, C.R. (2015). A randomized trial comparing the diagnostic accuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid to visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine for cervical cancer screening in HIV-infected women. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0118568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118568

Johnson, C.E., Mues, K.E., Mayne, S.L., & Kiblawi, A.N. (2008). Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A systematic review using the Health Belief Model. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 12(3), 232–241.

Jonah, L., Pefoyo, A.K., Lee, A., Hader, J., Strasberg, S., Kupets, R., . . . Tinmouth, J. (2017). Evaluation of the effect of an audit and feedback reporting tool on screening participation: The Primary Care Screening Activity Report (PCSAR). Preventive Medicine, 96, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.002

Kiran, T., Davie, S., Moineddin, R., & Lofters, A. (2018). Mailed letter versus phone call to increase uptake of cancer screening: A pragmatic, randomized trial. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 31(6), 857–868. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.06.170369

Krok-Schoen, J.L., Oliveri, J.M., Young, G.S., Katz, M.L., Tatum, C.M., & Paskett, E.D. (2016). Evaluating the stage of change model to a cervical cancer screening intervention among Ohio Appalachian women. Women and Health, 56(4), 468–486.

Lönnberg, S., Andreassen, T., Engesæter, B., Lilleng, R., Kleven, C., Skare, A., . . . Tropé, A. (2016). Impact of scheduled appointments on cervical screening participation in Norway: A randomised intervention. BMJ Open, 6(11), e013728.

Magnani, B., Harubin, B., Katz, J.F., Zuckerman, A.L., & Strohsnitter, W.C. (2016). See, test, and treat: A 5-year experience of pathologists driving cervical and breast cancer screening to underserved and underinsured populations. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 140(12), 1411–1422.

Maia, M.N., Peres de Oliveira da Silva, R., & Robeiro dos Santos, L.P. (2018). A organização do rastreamento do câncer do colo uterino por uma equipe de Saúde da Família no Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Medicina de Família e Comunidade, 13(40), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5712/rbmfc13(40)1633

Mbachu, C., Dim, C., & Ezeoke, U. (2017). Effects of peer health education on perception and practice of screening for cervical cancer among urban residential women in south-east Nigeria: A before and after study. BMC Women’s Health, 17(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0399-6

Mendes, L.C., Elias, T.C., & Silva, S.R. (2018). Knowledge of and adherence to Pap smear screening of public school students attending evening courses. Revista Mineira de Enfermagem, 22, e1079. https://doi.org/10.5935/1415-2762.20180009

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Naz, M.S.G., Kariman, N., Ebadi, A., Ozgoli, G., Ghasemi, V., & Fakari, F.R. (2018). Educational interventions for cervical cancer screening behavior of women: A systematic review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 19(4), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.875

Ndejjo, R., Mukama, T., Musabyimana, A., & Musoke, D. (2016). Uptake of cervical cancer screening and associated factors among women in rural Uganda: A cross sectional study. PLOS ONE, 11(2), e0149696.

O’Connor, M., McSherry, L.A., Dombrowski, S.U., Francis, J.J., Martin, C.M., O’Leary, J.J., & Sharp, L. (2021). Identifying ways to maximise cervical screening uptake: A qualitative study of GPs’ and practice nurses’ cervical cancer screening-related behaviours. HRB Open Research, 4, 44. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13246.1

O’Donovan, J., O’Donovan, C., & Nagraj, S. (2019). The role of community health workers in cervical cancer screening in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ Global Health, 4(3), e001452. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001452

Ouedraogo, Y., Furlane, G., Fruhauf, T., Badolo, O., Bonkoungou, M., Pleah, T., . . . Bazant, E.S. (2018). Expanding the single-visit approach for cervical cancer prevention: Successes and lessons from Burkina Faso. Global Health Science and Practice, 6(2), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.9745/ghsp-d-17-00326

Paulauskiene, J., Ivanauskiene, R., Skrodeniene, E., & Petkeviciene, J. (2019). Organised versus opportunistic cervical cancer screening in urban and rural regions of Lithuania. Medicina, 55(9), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55090570

Peitzmeier, S.M., Khullar, K., & Potter, J. (2016). Effectiveness of four outreach modalities to patients overdue for cervical cancer screening in the primary care setting: A randomized trial. Cancer Causes and Control, 27(9), 1081–1091.

Romero, L.S., Shimocomaqui, G.B., & Medeiros, A.B.R. (2017). Intervenção na prevenção e controle de câncer de colo uterino e mama numa unidade básica de saúde do nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Medicina de Família e Comunidade, 12(39), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5712/rbmfc12(39)1356

Savas, L.S., Atkinson, J.S., Figueroa-Solis, E., Valdes, A., Morales, P., Castle, P.E., & Fernández, M.E. (2021). A lay health worker intervention to improve breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas in El Paso, Texas: A randomized control trial. Preventive Medicine, 145, 106446. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106446

Shikha, S., Smita, J., Nayanjeet, C., Ruchi, P., Parul, S., Uma, M., . . . Pritpal, M. (2020). Experience of a ‘screen and treat’ program for secondary prevention of cervical cancer in Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 46(2), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14162

Sohn, E. (2020). Better cancer screening in resource-poor nations. Nature, 579(7800), S17–S19.

Staley, H., Shiraz, A., Shreeve, N., Bryant, A., Martin-Hirsch, P.P., & Gajjar, K. (2021). Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD002834. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub3

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R.L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Tavasoli, S.M., Pefoyo, A.J.K., Hader, J., Lee, A., & Kupets, R. (2016). Impact of invitation and reminder letters on cervical cancer screening participation rates in an organized screening program. Preventive Medicine, 88, 230–236.

Tchounga, B., Boni, S.P., Koffi, J.J., Horo, A.G., Tanon, A., Messou, E., . . . Jaquet, A. (2019). Cervical cancer screening uptake and correlates among HIV-infected women: A cross-sectional survey in Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa. BMJ Open, 9(8), e029882. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029882

Téguété, I., Tounkara, F.K., Diawara, B., Traoré, S., Koné, D., Bagayogo, A., . . . Traoré, C.B. (2021). A population-based combination strategy to improve the cervical cancer screening coverage rate in Bamako, Mali. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 100(4), 794–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14119

Thompson, B., Carosso, E.A., Jhingan, E., Wang, L., Holte, S.E., Byrd, T.L., . . . Duggan, C.R. (2017). Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer, 123(4), 666–674.

Trapero-Bertran, M., Pérez, A.A., de Sanjosé, S., Domínguez, J.M.M., Capriles, D.R., Martinez, A.R., . . . Sanchis, M.D. (2017). Cost-effectiveness of strategies to increase screening coverage for cervical cancer in Spain: The CRIVERVA study. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4115-0

Tsoa, E., Kone Pefoyo, A.J., Tsiplova, K., & Kupets, R. (2017). Evaluation of recall and reminder letters on retention rates in an organized cervical screening program. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 39(10), 845–853.

Vale, D.B., Silva, M.T., Discacciati, M.G., Polegatto, I., Teixeira, J.C., & Zeferino, L.C. (2021). Is the HPV-test more cost-effective than cytology in cervical cancer screening? An economic analysis from a middle-income country. PLOS ONE, 16(5), e0251688. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251688

Vale, D.B., Teixeira, J.C., Bragança, J.F., Derchain, S., Sarian, L.O., & Zeferino, L.C. (2021). Elimination of cervical cancer in low- and middle-income countries: Inequality of access and fragile healthcare systems. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 152(1), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13458

Vu, L.T.H., Tran, H.T.D., Nguyen, B.T., Bui, H.T.T., Nguyen, A.D., & Pham, N.B. (2018). Community-based screening for cervical cancer using visual inspection with acetic acid: Results and lessons learned from a pilot study in Vietnam. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 24(Suppl. 2), S3–S8.

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Wong, C.L., Choi, K.C., Law, B.M.H., Chan, D.N.S., & So, W.K.W. (2019). Effects of a community health worker–led multimedia intervention on the uptake of cervical cancer screening among South Asian women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3072. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173072

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO framework for strengthening and scaling-up of services for the management of invasive cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003231

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention (2nd ed.). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/342365

Zhang, D., Advani, S., Waller, J., Cupertino, A.-P., Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A., Chicaiza, A., . . . Braithwaite, D. (2020). Mobile technologies and cervical cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. JCO Global Oncology, 6, 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.19.00201

Zug, K.E., & Grube, W. (2014). Expanding the NP role in the cervical cancer prevention triad: Screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Women’s Healthcare, 2(3), 46–49.