Nipple-Areola Tattoos: Making the Right Referral

Purpose/Objectives: To examine oncology care providers’ knowledge of tattooing options for patients who have elected to have breast reconstruction as part of their breast cancer treatment.

Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Setting: A large metropolitan cancer center in New York and various locations across the United States.

Sample: 68 oncology care providers who work with women with breast cancer, distributed into two groups: RNs (n = 43) and non-RNs (n = 25).

Methods: Descriptive statistics were used to summarize online survey responses for the two groups, with inferential comparisons made with logistic regression models.

Main Research Variables: Healthcare profession, discussion of reconstructive tattoo options with patients, knowledge of providers of reconstructive tattoos outside of traditional healthcare settings, and recommendations made to patients.

Findings: RNs were significantly less likely to recommend a professional tattoo artist to a patient than non-RNs, despite a similar proportion of both groups believing that a tattoo artist would provide the patient with a better tattoo than healthcare providers (HCPs).

Conclusions: Additional research is needed to identify education deficits in HCPs regarding tattoo reconstruction options. HCPs are recommending potentially substandard options for nipple-areola tattooing, even though many believe that tattoo artists, who are outside of the traditional healthcare setting, could provide better outcomes for patients.

Implications for Nursing: Nurses and other HCPs require additional education about nipple-areola tattoo options for patients following breast cancer surgery.

Jump to a section

Breast cancer remains one of the most common malignancies in the United States, with an estimated 232,000 incident cases in 2014 (National Cancer Institute [NCI], n.d.). Although the incidence rate of breast cancer has gradually increased during the past four decades because of improvements in screening and treatment, the five-year survival rate has also increased from an estimated 75% in 1975 to more than 90% today (NCI, n.d.). A greater proportion of women are surviving longer with the disease after initial diagnosis, placing greater emphasis on their quality of life during the post-treatment period.

Among those patients who are able to receive breast-conserving treatment, nipple-areola tattoos are the final stage of a long, emotionally challenging road to recovery following breast cancer. The tattoos mark the end of chemotherapy, surgery, and uncertainty; for some, they also symbolize the transition from patient to survivor. Although reconstructive surgery frequently provides excellent outcomes as far as the form and shape of breasts, nipple-areola tattoos are often a neglected part of the breast reconstruction process.

Background

When performed by healthcare providers (HCPs) (e.g., physicians, nurses, physician assistants), shortcomings of nipple-areola tattoos may include poor pigment retention and color matching, lack of dimension, scarring, and increased healing time (Goh, Martin, Pandya, & Cutress, 2011; Jabor, Shayani, Collins, Karas, & Cohen, 2002). These deficiencies are directly related to the quality of ink used, as well as to HCPs’ lack of art training and substandard tattooing technique (Halvorson, Cormican, West, & Myers, 2014). HCPs usually learn tattooing through a brief course offered by medical tattoo companies. They are provided, on average, with only 100 hours of training, which is often offered by the manufacturer of the ink (Beau Institute, n.d.; Dermagrafix Permanent Cosmetic Studio, 2015; Eternal Beauty Cosmetics, 2009). Some may also receive additional peer training on the job. These HCPs are taught the basics of cross-contamination and how to operate the tattooing machine, but they rarely have an artistic background. As such, they have not been taught various artistic principles, such as how to achieve dimension or create a realistic image (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013).

Professional tattoo artists are possible alternative providers for patients completing nipple reconstruction after breast cancer. With their tattooing ability developed through an apprenticeship and under the supervision of a professional tattoo artist, they would be expected to have a superior command of artistic skills, resulting in improved outcomes for patients (Williams, 2014). These professionals may be a natural choice to play a role in the reconstruction process; however, a gap exists in the literature establishing how frequently patients seek tattoo artists to create the tattoos or how the outcomes differ between providers (tattoo artists versus HCPs).

As previously noted, most tattoo artists complete an apprenticeship under the guidance of a professional tattoo artist. However, the length of the apprenticeship varies (Williams, 2014), and it may be as short as 380 hours in Alaska to as long as three years in Pennsylvania (City of Philadelphia, n.d.; State of Alaska, 2014). In addition, just five states specify the completion of an apprenticeship as part of their regulatory requirements for tattoo artists (City of Philadelphia, n.d.; Southern Nevada Health District, 2015; State of Connecticut, 2015; State of Oklahoma, 2015; State of Tennessee, 2014). Substantial variability exists in training and regulatory requirements of the tattoo industry across states and even cities. Some states require individual artists to be licensed, whereas others require only the tattoo shop to be licensed; still others require both to be licensed (see Figure 1). Regulatory requirements tend to focus on health and sanitation to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Ten states specifically require that tattoo artists undergo some type of training regarding infection prevention, bloodborne pathogens, or sterilization prior to receiving a permit or license. In addition, four require cardiopulmonary resuscitation training, and three require first aid training. Although the vast majority of states recommend hepatitis B vaccination for tattoo artists, Montana is the only state to require it (CDC, 2013).

This variety in requirements and lack of standardization suggests that regulators are not as concerned with the quality or execution of tattoo designs. Although increased regulation may boost HCPs’ confidence in using tattoo artists, the regulatory environment, combined with the lack of data regarding comparative outcomes for providers of tattoos, may cause nurses or others involved in the recovery process to be reluctant to recommend tattoo artists for this service. In addition, regardless of whether a tattoo artist or HCP performs the tattooing procedure, the inks used by both are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2015).

Breast reconstruction is a significant contributing factor to a patient’s self-esteem (Keith et al., 2003; Veiga et al., 2010), and a poorly done tattoo created as part of that process could cause a patient to have a negative self-image. In fact, nipple-areola tattoos have been found to be one of the biggest areas of dissatisfaction among patients who have received nipple-areola reconstruction. Substandard color matching and shape are two of the most common complaints expressed by patients (Clarkson, Tracey, Eltigani, & Park, 2006; Goh et al., 2011; Jabor et al., 2002; Potter et al., 2007).

The breast cancer treatment process is a collaborative one, with plastic surgeons, oncologists, nurses, and other HCPs working together at different points during a patient’s recovery process. If a tattoo artist can provide the best possible tattoo for a patient, he or she may be one additional person to include in the multidisciplinary team. Some medical professionals have recently suggested that tattoo artists may do a better job than medical professionals at performing nipple-areola tattoos (Halvorson et al., 2014); however, recommendations from the medical community to include these individuals as a part of the reconstruction process are still limited. This may be because HCPs believe they can provide the best tattoos for patients (Clarkson et al., 2006; Potter et al., 2007). HCPs may also lack knowledge about alternatives for nipple-areola tattooing. The current study examines HCPs’ knowledge of options available for nipple-areola tattooing as part of the breast reconstruction process, as well as whether a lack of knowledge is one potential barrier to referral to tattoo artists.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with seven HCPs caring for women with breast cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York: a psychiatrist, an infusion nurse, a social worker, a plastic surgery nurse, a physician assistant to a plastic surgeon, a medical oncologist, and a surgical oncology nurse. Interviews focused on respondents’ knowledge of tattoo options, the type of patients they observed receiving nipple-areola tattoos, and tattoo-related concerns that patients had expressed to them as part of the breast reconstruction process.

A survey consisting of 22 questions was developed based on themes that emerged from these qualitative interviews. It was distributed using SurveyMonkey® (www.surveymonkey.com), and the survey link was emailed to clinicians specializing in breast cancer care who were associated with MSKCC and posted in online oncology nurse forums that reach nurses across the country. It was available to respondents for five weeks. All respondents were anonymous unless they chose to add their contact information at the end of the survey to be contacted for further questioning. Two reminder invitations were sent out at two and four weeks. The primary research interest was to determine if the likelihood of discussing options for nipple-areola tattooing and/or recommending tattoo artists differed between RNs and non-RNs. Based on the interviews conducted for development of the survey, the primary hypothesis was that RNs would be significantly less likely to recommend tattoo artists for reconstructive tattoos compared to non-RNs. Additional measures of interest included RN versus non-RN awareness that tattoo artists perform these nipple-areola tattoos, as well as their perceptions of the quality of the tattoos performed by tattoo artists, whether they would recommend tattoo artists to perform nipple-areola tattoos in the future, and what, if anything, prevented them from recommending tattoo artists to perform these tattoos. Respondents were considered to be RNs if they identified themselves as such. All other respondents were considered to be non-RNs.

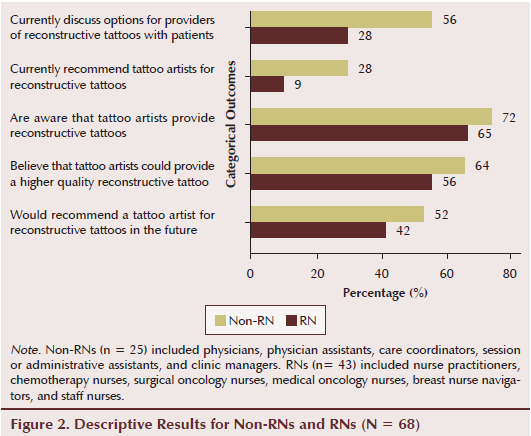

Logistic regression was used to determine if RNs and non-RNs differed in terms of the likelihood of the surveyed categorical outcomes (see Figure 2). Responses to individual questions were analyzed in separate models, where possible responses were “yes” or “no.” Internal consistency of these five outcomes was assessed by the Cronbach alpha for the overall sample and separately for RNs and non-RNs.

The primary outcome was whether the likelihood of currently recommending tattoo artists for nipple-areola tattoos was different between RNs and non-RNs. Based on the survey development interviews, the current authors expected that a minority of respondents would currently recommend tattoo artists to perform these tattoos. Assuming that 17% of RNs and 50% of non-RNs (odds ratio [OR] = 0.2) currently recommend tattoo artists, the study had approximately 80% power with 5% type 1 error (two-sided) with a total sample size of 68 respondents.

Univariate logistic regression and ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to compare RNs and non-RNs on the primary outcome, as well as on the outcomes of recommending a tattoo artist to a patient and their beliefs regarding a tattoo artist’s abilities. In addition, potential confounding by whether a respondent had a tattoo was assessed in multivariate logistic regression models. Likelihood ratio p values of less than 0.05 (two-sided) were considered statistically significant, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

Findings

The sample was comprised of 43 RNs and 25 non-RNs. RNs included nurse practitioners, chemotherapy nurses, surgical oncology nurses, medical oncology nurses, breast nurse navigators, and staff nurses. Non-RNs included physicians, physician assistants, care coordinators, session or administrative assistants, and clinic managers. Similar majorities of RNs and non-RNs reported not having a tattoo themselves. The standardized Cronbach alpha for the five questions answered by RNs and non-RNs was 0.69, indicating sufficient reliability, and it was higher for non-RNs (0.74) than for RNs (0.64).

In logistic regression models, RNs were significantly less likely to currently discuss options for providers of nipple-areola tattoos with patients (OR [95% CI] = 0.3 [0.11, 0.86], p = 0.02) and currently recommend tattoo artists for this work (OR [95% CI] = 0.26 [0.07, 1], p = 0.04). In multivariate logistic models, these differences remained statistically significant after adjusting for respondents’ reporting of having a tattoo (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04, respectively). No significant differences were noted between RNs and non-RNs in their awareness that tattoo artists provide nipple-areola tattoos (OR [95% CI] = 0.73 [0.25, 2.13], p = 0.56), belief that tattoo artists could provide a higher quality tattoo (OR [95% CI] = 0.71 [0.26, 1.96], p = 0.51), or likelihood of recommending a tattoo artist in the future (OR [95% CI] = 0.67 [0.25, 1.79], p = 0.42).

Regardless of their healthcare profession, the majority of respondents across groups currently do not recommend tattoo artists to their patients for nipple-areola tattoos (n = 57). The primary reason these HCPs do not currently recommend tattoo artists for the procedure is a belief that their patients would prefer to receive a tattoo in a medical setting (n = 33). In addition, 14 of these HCPs responded that they believe patients would be too intimidated by the prospect of going to a tattoo shop for nipple-areola tattooing, and 9 of these HCPs said they believe tattoo shops lack the proper hygiene to perform the procedure.

No respondents expressed a concern that tattoo artists would not do a good job on nipple-areola tattoos. Significantly, these responses were based on respondents’ perceptions of patients’ feelings, as opposed to direct patient feedback. In addition, 31 respondents had seen a nipple-areola tattoo performed by a tattoo artist, and none had had a patient who experienced any sort of complication from a tattoo artist’s tattoo.

Similar majorities of RNs (n = 28) and non-RNs (n = 18) were aware that tattoo artists performed nipple-areola tattoos (p = 0.55). Despite a minority of respondents currently recommending tattoo artists for the procedure, a similar majority of RNs and non-RNs (n = 24 and n = 16, respectively; p = 0.51) noted that they believed a tattoo artist would provide a patient with a higher quality tattoo than would an HCP. Similar proportions of RNs and non-RNs responded that they would recommend a tattoo artist for nipple-areola tattoos in the future (p = 0.42) now that they had been made aware of the topic; across groups, this proportion is 46%, whereas the proportion of respondents who currently recommend tattoo artists for this procedure is 16%. This finding contributes to the current authors’ belief that increased education of HCPs can significantly affect decision-making discussions between HCPs and patients seeking nipple reconstruction and nipple-areola tattooing.

Discussion

RNs were less likely than non-RNs to recommend that a tattoo artist perform nipple-areola tattoos. This may be because of workplace policies surrounding RN recommendations, the comfort level of RNs in making recommendations related to treatment decision making in general, or the convenience of keeping patients in the office to perform the tattooing. Economic factors may also influence patients and HCPs. For example, by recommending tattoo artists for nipple-areola tattoos, HCPs may potentially lose substantial business and, therefore, are motivated to keep patients in-house for such procedures. They may also be concerned that some patients may not be able to afford tattoos offered outside of the medical facility. However, patients and HCPs may not be aware that nipple-areola tattoos are a billable medical procedure that may be covered by patients’ health insurance plans. Several large insurance companies clearly state in their policies that such tattooing is covered when documentation is available showing that the procedure is to “correct deformity resulting from disease, trauma, or previous therapeutic process” (Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Mississippi, 2015, para. 2). If the tattoo artist is not an employee of a healthcare facility that is able to directly bill an insurance company, patients may be able to pay out of pocket and be reimbursed by their insurance company (Halvorson et al., 2014).

Limitations

The study had a few limitations. For example, a sufficient number of respondents was not available to determine if HCPs’ having personal tattoos would make them more likely to recommend that a tattoo artist perform nipple-areola tattoos; only a few respondents had tattoos (n = 9) and were, consequently, more familiar with a tattoo shop’s process. HCPs with tattoos may also be more comfortable recommending that tattoo artists perform nipple-areola tattoos if they, personally, had a positive experience with them.

The current authors assumed that electronic data collection would help to capture a broader and more diverse audience (Cope, 2014); however, even this methodology has its limitations. Although electronic data collection is convenient, it limits the population to those who have access to a computer. In addition, response rates to electronic healthcare surveys tend to be lower than other survey methods (e.g., mailed questionnaire, telephone interview) (Scott et al., 2011).

Another limitation of collecting data via an online survey is that no reliable way of knowing who completed it exists. In addition, the same person could potentially respond to the survey multiple times; however, because no incentive for completing this survey existed, the likelihood of this occurring is assumed to be small.

Implications for Nursing and Conclusion

Nipple-areola tattoos provided by HCPs may not be the best quality tattoos available to patients. In general, HCPs want their patients to have the best care possible and regularly refer patients to other providers to achieve this goal. This practice should be extended to nipple-areola tattooing. Tattoo artists may do a better job of tattooing areolae on reconstructed breasts because of their training and understanding of artistic principles (e.g., coloring, shadowing, depth, use of various materials). Given the higher quality of tattoos that a tattoo artist can provide, HCPs should consider incorporating a tattoo artist into the healthcare team. HCPs could do so by thoroughly researching tattoo shops and tattoo artists that they could recommend to patients in the future, encouraging an artist to join their facility, or seeking formal, in-depth tattoo training that is more consistent with the apprenticeship completed by tattoo artists.

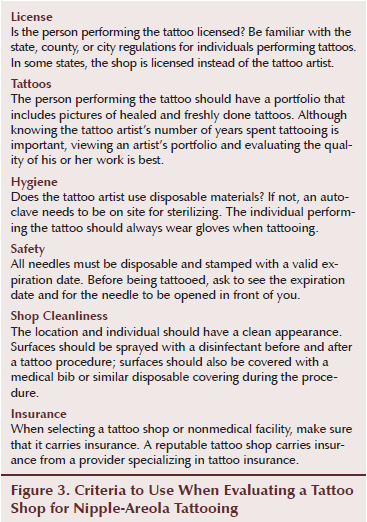

HCPs can assist their patients in the selection of a tattoo provider, whether it be a medical professional or tattoo artist, by providing some basic information. Figure 3 offers a guide that may help HCPs and patients evaluate individuals and facilities for nipple-areola tattooing.

A lack of knowledge or empowerment to discuss nipple-areola tattooing alternatives outside of the medical setting is preventing patients from receiving information about all possible options for nipple-areola reconstruction. This may be contributing toward low patient satisfaction rates after nipple reconstruction in the medical setting (Clarkson et al., 2006). Nurses should be educated about all nipple-areola tattoo options available to patients, and they should work with the multidisciplinary team to ensure that providers in the healthcare setting performing nipple-areola tattoos are appropriately trained and licensed. In addition, nurses may help by collaborating with patients to identify local tattoo shops that are experienced in performing nipple-areola tattoos, meet health and safety standards, and are willing to work with patients’ health insurance companies for reimbursement. Nurses may also champion a process change involving regularly bringing a tattoo artist into the medical facility to perform tattooing in lieu of a less experienced HCP, with the aim of providing higher quality tattoos to patients who have undergone breast reconstruction as part of their breast cancer treatment.

References

Beau Institute. (n.d.). Beau Institute permanent makeup primary training. Retrieved from http://www.beauinstitute.com/primary-permanent-makeup-training.php

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Mississippi. (2015). Tattooing. Retrieved from http://www.bcbsms.com/com/bcbsms/apps/policysearch/views/viewpolicy.php…

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Body art. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/body_art/stateregs.html

City of Philadelphia. (n.d.). Body art info. Retrieved from http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/Body_Art_Info.pdf

Clarkson, J.H., Tracey, A., Eltigani, E., & Park, A. (2006). The patient’s experience of a nurse-led nipple tattoo service: A successful program in Warwickshire. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, 59, 1058–1062. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2005.09.049

Cope, D.G. (2014). Using electronic surveys in nursing research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 681–682. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.681-682

Dermagrafix Permanent Cosmetic Studio. (2015). Classes. Retrieved from http://www.dermagrafix.net/training/classes

Eternal Beauty Cosmetics. (2009). Training. Retrieved from http://www.eternal-beauty-cosmetics.com/training.html

Goh, S.C., Martin, N.A., Pandya, A.N., & Cutress, R.I. (2011). Patient satisfaction following nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and tattooing. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, 64, 360–363. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.05.010

Halvorson, E.G., Cormican, M., West, M.E., & Myers, V. (2014). Three-dimensional nipple-areola tattooing: A new technique with superior results. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 133, 1073–1075. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000000144

Jabor, M.A., Shayani, P., Collins, D.R., Jr., Karas, T., & Cohen, B.E. (2002). Nipple-areola reconstruction: Satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 110, 457–463. doi:10.1097/00006534-200208000-00013

Keith, D.J., Walker, M.B., Walker, L.G., Heys, S.D., Sarkar, T.K., Hutcheon, A.W., & Eremin, O. (2003). Women who wish breast reconstruction: Characteristics, fears, and hopes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 111, 1051–1056. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000046247.56810.40

National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). SEER stat fact sheets: Breast cancer. Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html

Potter, S., Barker, J., Willoughby, L., Perrott, E., Cawthorn, S.J., & Sahu, A.K. (2007). Patient satisfaction and time-saving implications of a nurse-led nipple and areola reconstitution service following breast reconstruction. Breast, 16, 293–296. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.004

Scott, A., Jeon, S.H., Joyce, C.M., Humphreys, J.S., Kalb, G., Witt, J., & Leahy, A. (2011). A randomised trial and economic evaluation of the effect of response mode on response rate, response bias, and item non-response in a survey of doctors. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 126. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-126

Southern Nevada Health District. (2015). Body art. Retrieved from http://www.southernnevadahealthdistrict.org/body-art/apprentice-require…

State of Alaska. (2014). Body piercing, tattooing, and permanent cosmetic coloring. Retrieved from http://laborstats.alaska.gov/dlo/tattoo.htm

State of Connecticut. (2015). Tattoo licensing after 1/1/2015. Retrieved from http://www.ct.gov/dph/cwp/view.asp?a=3121&q=545770

State of Oklahoma. (2015). How to become a full-time licensed tattoo or body piercing artist in Oklahoma. Retrieved from http://www.ok.gov/health/Protective_Health/Consumer_Protection_Division…

State of Tennessee. (2014). Tenn. Code Ann. § 62-38-201. Retrieved from http://health.state.tn.us/EH/PDF/Tattoo%20law.pdf

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015). Tattoos and permanent makeup: Guide to resources. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm107327.htm

Veiga, D.F., Veiga-Filho, J., Ribeiro, L.M., Archangelo, I., Jr., Balbino, P.F., Caetano, L.V., . . . Ferreira, L.M. (2010). Quality-of-life and self-esteem outcomes after oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 125, 811–817. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ccdac5

Williams, G. (2014, March 6). The renaissance of the tattoo. Finweek, 24–29. Retrieved from http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/94940425/renaissance-tattoo

About the Author(s)

Dina DiCenso, MSF, PhD, is the owner of Gristle Tattoo and a student in the College of Nursing at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and Erica Fischer-Cartlidge, MSN, CNS, CBCN®, AOCNS®, is a clinical nurse specialist in Outpatient Breast Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, both in New York, NY. No financial relationships to disclose. DiCenso can be reached at dina.dicenso@downstate.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted February 2015. Accepted for publication May 8, 2015.)