Mental Health Distress: Oncology Nurses’ Strategies and Barriers in Identifying Distress in Patients With Cancer

Background: Oncology nurses have an important role in identifying mental health distress; however, the research to date indicates that oncology nurses often do not accurately detect this distress.

Objectives: The aim of this study is to explore oncology nurses’ perspectives on indicators of distress in patients, the strategies they use in identifying these signs of distress, and the barriers they face in recognizing these indicators.

Methods: Twenty oncology nurses were interviewed. The study used the grounded theory method of data collection and analysis.

Findings: Nurses relied on a number of emotional and behavioral indicators to assess distress. Nurses reported that indicators of mental health distress often were expressed by patients or their caregivers. Strategies to identify distress were limited, with nurses reporting that their only method was directly asking the patient. Barriers to identifying distress included patients concealing distress, nurses’ lack of training, and time constraints.

Jump to a section

A cancer diagnosis, particularly for the first time, can cause a major upheaval in a person’s life. During the treatment trajectory, people with cancer can suffer tremendous physical and emotional distress (Kaul et al., 2017; Zebrack et al., 2015). The literature indicates that about 30% of people with cancer will develop an anxiety or mood disorder (Nakash, Liphshitz, Keinan-Boker, & Levav, 2013). One study that looked at the World Mental Health Surveys from 13 countries found that the prevalence rates for mood and anxiety disorders in a given year were higher in patients with cancer (18%) when compared with people who did not have cancer (13%) (Nakash et al., 2014).

Appropriate treatment of mental health disorders in patients with cancer can affect the trajectory of the disease (Carlson & Bultz, 2004); the length of hospital stay (Prieto et al., 2002); treatment adherence and efficacy (Kennard et al., 2004); satisfaction with treatment (Bui, Ostir, Kuo, Freeman, & Goodwin, 2005); and possibly prognosis and quality of life (Institute of Medicine, 2008; Sanjida et al., 2016). However, several studies have documented a treatment gap among patients with cancer when it comes to addressing their mental health (Kaul et al., 2017; Nakash et al., 2013). The treatment gap refers to the proportion of individuals with cancer who also have comorbid mental disorders that are not receiving treatment. This gap is universal, with 40% of people meeting this criterion in high- and low-middle–income countries (Nakash et al., 2013). Untreated comorbidities may have a severely negative effect on the illness trajectory and on patients’ quality of life (Singer, Das-Munshi, & Brähler, 2010).

A timely and accurate diagnosis of mental health disorders is the basis for mental health treatment and is critical to increase use of services when needed and reduce the treatment gap. Screening for mental health distress is so important that it has been recommended as a standard of care by several organizations, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (Lazenby, 2014; National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, 2013) and American College of Surgeons (2016). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a reliable measure to screen for distress (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983). This is a self-report scale with 14 items, including symptoms of anxiety and depression (Walker et al., 2007). Another frequently used measure is the Distress Thermometer (Holland & Bultz, 2007), which is a self-report measure consisting of a line with a 0–10 scale, anchored at the 0 point with “no distress” and at the 10 point with “extreme distress.” Patients who score 4 and above are considered distressed enough to need intervention. The measure has been used extensively and successfully in research with patients with cancer (Donovan, Grassi, McGinty, & Jacobsen, 2014; O’Donnell, 2013).

Despite these recommendations and the availability of reliable tools to measure distress, the research indicates that healthcare providers (HCPs) frequently fail to recognize mental health disorders in patients with cancer (Holland & Alici, 2010; Miyajima et al., 2014; Werner, Stenner, & Schüz, 2012). Most published data suggest that HCPs’ ability to accurately detect emotional distress in patients with cancer is poor (Fallowfield, Ratcliffe, Jenkins, & Saul, 2001; Werner et al., 2012). For example, in one study (Söllner et al., 2001), only 30% of patients with cancer who were severely distressed were identified by their oncologists as experiencing any mental health issues. Although the recognition of emotional distress can be hampered by the unwillingness of patients to disclose such concerns, HCPs are also frequently reluctant to probe these areas adequately (Granek, Nakash, Ben-David, Shapira, & Ariad, 2018a; SÖllner et al., 2001).

As this review indicates, mental health distress in patients with cancer is common, and accurate identification of this distress is critical for improving the quality of life of patients and their families. Oncology nurses play an important role when it comes to identifying distress, because they have frequent and ongoing contact with patients and their families (Estes & Karten, 2014; Vitek, Rosenzweig, & Stollings, 2007). For example, Musiello et al. (2017) pilot tested routine screening by a psychologist and a nurse in an outpatient oncology clinic. Using the Distress Thermometer, they found that nurses spent more time talking to patients about the screening results and were more likely to make referrals to the appropriate services than the psychologists (Musiello et al., 2017).

Despite this central role in potentially identifying distress, the research to date indicates that much like other HCPs, oncology nurses overall often do not detect patients’ mental health distress accurately (Kaneko et al., 2013; Miyajima et al., 2014; Nakaguchi et al., 2013). For example, McDonald et al. (1999) looked at 40 clinic nurses in 25 community-based ambulatory oncology clinics and found that, of 1,109 patients with cancer, nurses were able to correctly identify clinical depression only 29% of the time when the depression was mild, and only 14% of the time when the depression was severe. McDonald et al. (1999) concluded that nurses tended to underestimate the level of depression in their patients, particularly for those who were suffering from severe depression. Similarly, in another study conducted in Japan (Nakaguchi et al., 2013), 17 oncology nurses were asked to rate the supportive care needs of 439 patients who also filled out a needs assessment. The concordance rates between patients’ and nurses’ assessments of supportive care needs was low, and the authors concluded that nurses’ recognition of patients’ psychological needs was poor (Nakaguchi et al., 2013).

Research on oncology nurses’ self-perception corroborates these findings. In some survey studies, oncology nurses expressed concern about their abilities to detect distress in patients with cancer (Kaneko et al., 2013; Pehlivan & Küçük, 2016). In a study by Kaneko et al. (2013) of 88 oncology nurses who filled out a questionnaire, more than half reported that they were very concerned about their abilities to assess anxiety and depression of patients with cancer. In another study of 157 nurses who were evaluated for their ability to detect distress, more than 20% of the sample reported that they felt they did not have the knowledge to perform psychosocial evaluations on patients (Pehlivan & Küçük, 2016).

Oncology nurses’ barriers in identifying mental health distress in patients with cancer include a lack of time and resources (Dilworth, Higgins, Parker, Kelly, & Turner, 2014; Güner, Hiçdurmaz, Kocaman Yıldırım, & İnci, 2018; Turner et al., 2018), lack of knowledge (Güner et al., 2018), and lack of privacy to talk to patients about their potential distress (Turner et al., 2018).

Given that patients with cancer often suffer from mental health distress that is not identified and not treated by their HCPs, and given the evidence that this treatment gap may be caused by oncology nurses’ inability to accurately detect mental health distress, this study aimed to explore how oncology nurses address this problem. In this study, oncology nurses were asked directly about what they look for and how they identify mental health distress in patients with cancer, with an additional focus on strategies for and barriers to identifying distress from their own perspectives.

Methods

Design and Participants

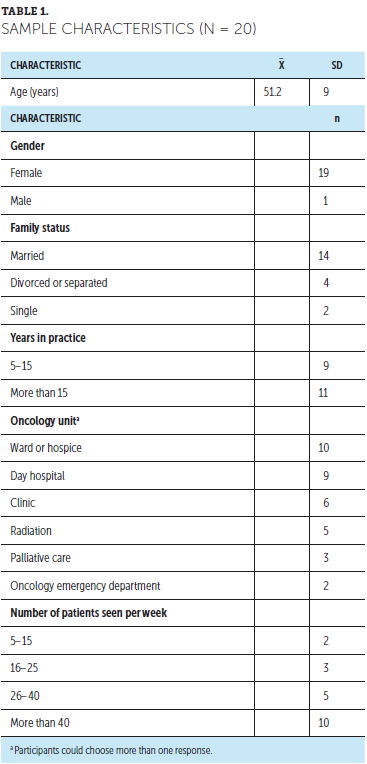

This study came out of a larger research project examining how oncology HCPs identify suicidality in patients with cancer (Granek et al., 2017, 2018a, 2018b). The study used the grounded theory method of data collection and analysis (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Grounded theory emphasizes a method of inquiry and the products of that inquiry. It can be used to explore people’s experiences and can aim toward theory development. Although a theoretical model was developed in previous articles from this project (Granek et al., 2017), the research question asked in this study did not lend itself well to developing a theoretical model. Nonetheless, the study employed all the hallmarks of grounded theory, including no preconceived codes or categories and the use of theoretical sampling, memos, line-by-line coding, and constant comparison in data analysis. Recruitment involved 20 nurses who were interviewed about their perceptions on indicators of mental health distress in patients with cancer. Nurses were asked about what strategies they use in identifying this distress and the barriers they face in recognizing distress. All nurses who participated in the study worked exclusively with patients with cancer in oncology units (see Table 1).

The principal investigator is a psychologist with a background in mental health in the oncology context. To maximize perspectives on the study topic and reduce bias toward mental health services, an interprofessional research team was composed; it included a health psychologist, clinical psychologist, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, and research assistant with a social sciences background. Discussions resulted in a diversity of professional and disciplinary views about the emerging dataset. When discussing indications of mental health distress in patients, the psychologists were able to describe definitions of clinical depression and anxiety, and the medical and radiation oncologists were able to shed light on the importance of physical symptoms as indications of distress.

Procedure

Research ethics board approvals were obtained at the start of the study. Potential participants were emailed information about the study by the co-investigators and asked to respond if they wished to hear more about the research. Twenty nurses responded. Participants signed a consent form before beginning the interview. A semistructured interview guide was used. All interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed, with all information that could identify participants removed from the transcripts. Questions focused on how nurses identify mental health distress in patients, including probes about symptoms they look out for, things that stand out to them that require special attention, and concrete examples of patients in whom distress was identified. Questions also focused on challenges and struggles in identifying distress in patients.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis took place at the same time, and analysis proceeded with line-by-line coding of the transcripts. Analysis was inductive. Categories and codes emerged from participants’ stories, rather than from codes or categories that were preconceived. Throughout the analysis, constant comparison was used to explore the relationships within and across codes and categories. The study team met frequently to discuss emerging findings and to ensure consistency in the emerging coding scheme throughout the process of data collection and analysis. Data collection was stopped when data saturation was reached. NVivo, version 10.0, was used to store and organize the data.

Findings

Identification of Mental Health Distress

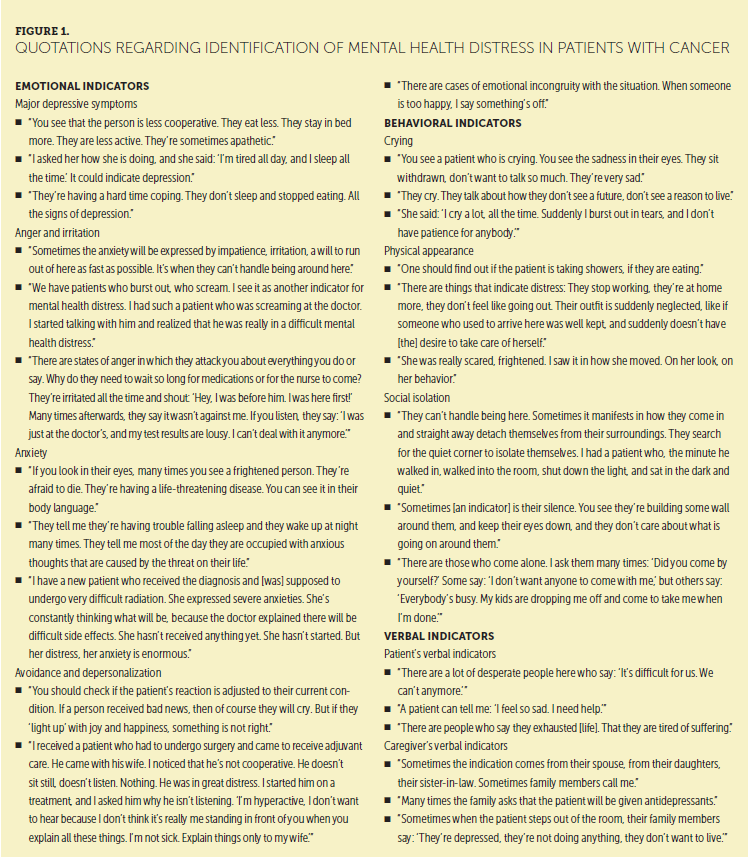

When oncology nurses were asked to speak about identifying mental health distress in patients with cancer, they reported on three major themes: (a) emotional indicators, with the subthemes of major depressive symptoms, anger and irritation, anxiety, and avoidance and depersonalization; (b) behavioral indicators, including crying, the patient’s physical appearance, and the patient’s social isolation; and (c) verbal indicators, including expressions of concern from the patients and their families (see Figure 1).

Emotional Indicators of Mental Health Distress

Nurses reported that the first symptoms they noticed that indicated mental health distress in patients were indicators of major depressive disorder. These symptoms could include anhedonia, apathy and withdrawal, general sadness, hopelessness and helplessness, flat affect, and despondency. Nurses also considered expressions of irritability and anger as potential signs of mental health distress. This could be expressed by patients by being generally irritable, or it could be anger and aggression directed toward the nurses or doctors treating the patients.

Fear and anxiety also were reported as signs of mental health distress. This anxiety could be around the diagnosis, the prognosis, treatments, the unknown, and death and dying. Signs of this anxiety in patients included experiencing rumination and intrusive thoughts, being uncooperative, being restless, and having difficulties sleeping. Nurses reported that when patients appeared to have an incongruent response to the treatment, or when they wanted to avoid all conversation about their condition, it could indicate mental health distress in the form of avoidance and depersonalization.

Behavioral Indicators of Mental Health Distress

Nurses reported that an obvious sign of mental health distress in patients was when they cried while receiving treatments or while talking about their condition. The way a patient looked also could indicate mental health distress. Examples included when a patient looked disheveled or appeared to be neglecting activities of daily living, such as personal hygiene and diet (e.g., not showering, eating less, appearing to be unkempt). Nurses noted that patients who isolated themselves out of choice or who appeared to be lonely without any social support could also indicate mental health distress.

Verbal Indicators of Mental Health Distress

Nurses reported that patients often verbalize their mental health distress explicitly. These indicators included statements like the following:

• “I’m sick and tired of this.”

• “I want to die.”

• “I don’t want to live in pain.”

• “I don’t have meaning in life.”

• “I don’t want to suffer.”

• “It’s too hard to cope.”

• “I’m in distress.”

In addition to a patient’s verbal indicators of distress, nurses reported that family members or caregivers often talked to the nurse about the patient’s mental state. This included reporting on the patient’s depression, asking that the patient be given antidepressants, or asking the nurse to intervene to help the patient with distress.

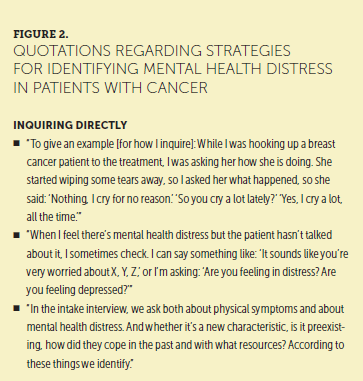

Strategies for Identifying Mental Health Distress

When nurses were asked about their strategies for identifying mental health distress in patients, they reported only on one theme that involved inquiring directly with patients. Supporting quotations are presented in Figure 2.

Nurses reported that they asked patients directly about how they were doing in multiple domains of their life. This included asking patients about their work; how they were feeling acutely and how they feel on a day-to-day basis; and how they were doing generally, physically and emotionally. In addition, nurses reported that they inquired about how they were before the disease and how they were doing currently in each of these domains to assess the level of their distress.

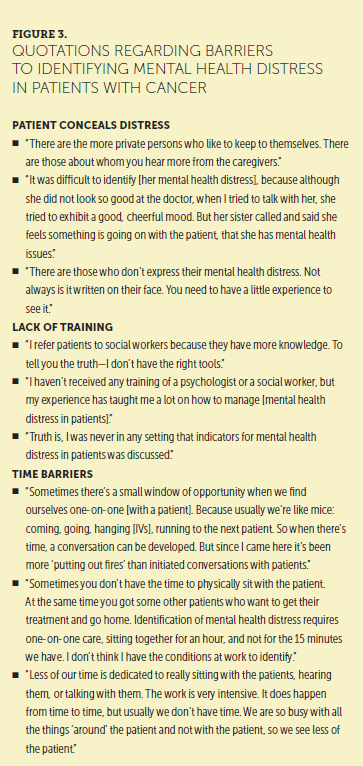

Barriers to Identifying Mental Health Distress

When asked to report on barriers to identifying mental health distress in patients, nurses spoke about three main themes that included patients concealing the distress, nurses’ lack of training to identify distress, and time constraints. Supporting quotations are presented in Figure 3.

One barrier in the detection of mental health distress is when patients themselves concealed their feelings from the healthcare staff. Nurses reported that this distress often was mentioned by caregivers of these patients but rarely seen by the healthcare staff.

Oncology nurses reported that they had no formal training in the identification of mental health distress. In their view, this was a significant barrier to helping patients. The only nurses who did receive training on identification of mental health distress were those who had training in supportive or end-of-life care. Therefore, identification of distress was based on experience rather than formal training.

Finally, nurses reported that a major barrier to identifying mental health distress was a lack of time to sit and listen to patients. Nurses also reported being so overburdened with practical care responsibilities that they rarely had time to get to know patients and talk to them about their emotional well-being.

Discussion

This study explored oncology nurses’ identification of mental health distress in patients. Previous studies have surveyed nurses about their abilities to identify distress or examined the concordance rate between patients’ assessment of their psychosocial needs and nurses’ abilities to accurately identify these needs (Kaneko et al., 2013; McDonald et al., 1999; Nakaguchi et al., 2013). To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the few studies to explore in-depth what nurses look for when identifying distress and what challenges they face in this task. The authors found that nurses relied on a number of indicators to assess emotional distress. These included emotional indicators, such as symptoms of major depressive disorder, anger and irritation, anxiety or fear, and avoidance or depersonalization. Behavioral indicators included crying, physical appearance, and social isolation. Finally, nurses reported that indicators of mental health distress often came directly from patients or their caregivers. Strategies for identifying mental health distress were limited, with nurses directly asking patients as their only approach. Finally, barriers to identification of distress included patients concealing distress, nurses’ lack of training, and time constraints.

These findings help illustrate nurses’ abilities to correctly name indicators of distress. For example, symptoms of major depressive disorder (e.g., poor appetite, apathy, sleepiness, seeming depressed) are appropriate cues to follow up on in patients with cancer. Other indicators reported, such as crying, physical appearance, anger, and social isolation, are more ambiguous and may or may not indicate emotional distress in patients. Nonetheless, the naming of these indicators suggests that oncology nurses are highly attuned to patients’ affective and physical state and rely on a number of cues to help them assess whether a patient is in distress. Conducting direct observations using explicit diagnostic questions provides more reliable diagnostic information and reduces bias (Nakash & Alegría, 2013).

However, more concerning findings from this study pertain to the limited strategies in identifying distress and the barriers listed in attending to this task. Asking patients directly is one effective way to assess distress, but it is limited in scope, particularly when administered in an inconsistent and unstructured manner. Some patients may be reluctant to answer these personal questions, and asking patients in an ad hoc way about their distress may not generate an accurate assessment of their emotional state. Other research, primarily among patients receiving psychiatric care, suggests that using ad hoc strategies for assessment can result in missing information and misdiagnosis (Nakash & Nagar, 2018).

Barriers to identification of distress, including lack of training and the perception that patients are concealing their distress, also can be addressed. A few studies have evaluated the efficacy of communication skills training for oncology nurses to improve detection of mental health distress in patients (Brown et al., 2009; Fukui, Ogawa, Ohtsuka, & Fukui, 2009). For example, one randomized controlled trial found that nurses who received communication skills training were better able to detect distress in newly diagnosed patients with cancer compared to those who did not receive the training (Fukui et al., 2009).

Limitations

For this study, selection bias may pose a risk to generalizability, because it is possible that nurses who agreed to participate in the study were those who felt more comfortable with and skilled in managing issues related to emotional distress among patients. It is plausible that the challenge of making correct diagnostic decisions and recognizing emotional distress may be even more prominent among the oncology nursing community at large. Further research could include surveying the patients themselves to see whether a treatment gap exists between patients’ needs and nurses’ ability to identify them. In addition, the data presented in this study can be supplemented by recording clinical encounters and analyzing what transpires in these interactions and where nurses may miss opportunities to identify patients’ distress.

Implications for Practice and Research

A cost-effective solution to address time limitations is conducting a short systematic screening for emotional distress (Adler & Page, 2007; Institute of Medicine, 2008). Diagnostic determinations of mental health distress in the oncology context are frequently made in environments that are low on resources and high on demands. Therefore, the use of any diagnostic system must address missing information. One potential approach to increasing diagnostic efficiency is using question probes to make an accurate psychiatric diagnosis. Probes to identify major depressive disorder can include questions assessing mood (low or depressed) and interest or pleasure (diminished or reduced). A study conducted among patients in outpatient mental health clinics showed that using these probes can significantly improve the accuracy of diagnostic decisions (Nakash, Nagar, & Kanat-Maymon, 2015). Future research can examine whether these probes or other screening questions can improve diagnostic decisions in oncology care.

A different approach to facilitating a time-efficient assessment of emotional distress can include using reliable and valid screening measures for prevalent mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression. Implementing such an approach will require a systematic screening of all patients to avoid bias in evaluation. Patients who meet the cutoff points can be followed up with by a thorough assessment by an oncology nurse or a social worker. Systematic screening for emotional distress fosters a holistic and comprehensive approach to care for patients with cancer (Adler & Page, 2007; Institute of Medicine, 2008). One commonly used measure for emotional distress screening is the Distress Thermometer (Holland & Bultz, 2007). This is a one-item self-report measure that is simple to administer and has been recommended for clinical use in oncology care (Donovan et al., 2014; O’Donnell, 2013), including by oncology nurses (Vitek et al., 2007). To date, there is limited empirical research that has examined outcomes of systematic screening for mental health disorders among patients with cancer (Carlson, Waller, & Mitchell, 2012).

This study’s findings emphasize the need to allocate appropriate resources (primarily dedicated effort time) to help nurses identify and address the mental health concerns of patients. In addition, to provide integrative care, nurses can receive basic training to systematically identify mental health distress and, perhaps more importantly, to provide initial response to alleviate the emotional suffering of patients. Such training can provide a foundation about mental health concerns, as well as tools to address these concerns. Nurses have a critical role as gatekeepers in recognizing emotional distress and providing initial response and, when needed, appropriate referral to specialized care.

Stepped Care

To facilitate a stepped care model, nurses can receive training to provide low-intensity psychological interventions (Bennet-Levy, Richards, & Farrand, 2010), which generally are based on cognitive behavioral therapy and delivered via written materials or information technology with limited professional guidance. Implementing low-intensity interventions in the general population (e.g., school counseling) can reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, studies among primary care physicians showed that they can be trained to deliver initial care of common mental disorders, particularly for uncomplicated cases (Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, 2010; Araya et al., 2003; Cuijpers, Donker, van Straten, Li, & Andersson, 2010; Osborn, Demoncada, & Feuerstein, 2006; Tatrow & Montgomery, 2006). Therefore, stepped care can significantly improve the accessibility and availability of services and provide a model for holistic care for comorbid mental health disorders for patients with chronic illnesses. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has recommended that different care options be offered, depending on symptom presentation and general clinical information. Across these different options, the role of HCPs is critical in mitigating the severe consequences of comorbid mental health disorders (Andersen et al., 2014). Being able to provide integrated care will not only improve patient care but also will improve oncology nurses’ knowledge and competency in identifying emotional distress. [[{"fid":"48901","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

Conclusion

Identifying emotional distress among patients with cancer is only the first step to providing holistic psychosocial care and diminishing the mental health treatment gap. Attention can be given to implementing training models that help nurses improve their communication skills in general and their recognition of potentially treatable anxiety and depression. Referral to specialized mental health care should be offered to patients for whom an increased risk is identified. This stepped care can ensure the delivery of evidence-based treatment (psychotherapy and psychopharmacology) to patients who need treatment for their emotional distress. [[{"fid":"48906","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{"format":"default","alignment":"","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"2"}}]]

About the Author(s)

Leeat Granek, PhD, is an assistant professor and the head of the gerontology and sociology of health programs in the Department of Public Health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beer Sheva, Israel; Ora Nakash, PhD, is a professor in the School for Social Work at Smith College in Northampton, MA; Samuel Ariad, MD, is a professor and physician emeritus in the Department of Oncology at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; Shahar Shapira, MA, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Gender Studies at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada; and Merav Ben-David, MD, is a senior lecturer at the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University in Israel. The authors take full responsibility for this content. This work was supported by a pilot research grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Granek can be reached at leeatg@gmail.com, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2018. Accepted July 23, 2018.)

References

Adler, N.E., & Page, A.E. (2007). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

American College of Surgeons. (2016). Cancer program standards: Ensuring patient-centered care. Retrieved from https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/2016%2…

Andersen, B.L., DeRubeis, R.J., Berman, B.S., Gruman, J., Champion, V.L., Massie, M.J., . . . Rowland, J.H. (2014). Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 1605–1619. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611

Andrews, G., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M.G., McEvoy, P., & Titov, N. (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 5(10), e13196. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013196

Araya, R., Rojas, G., Fritsch, R., Gaete, J., Rojas, M., Simon, G., & Peters, T.J. (2003). Treating depression in primary care in low-income women in Santiago, Chile: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet, 361, 995–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12825-5

Bennet-Levy, J., Richards, D., & Farrand, P. (2010). Low intensity CBT interventions: A revolution in mental health care. In J. Bennet-Levy, D.A. Richards, P. Farrand, H. Christensen, K. Griffiths, & D. Kavanagh (Eds.), Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions (pp. 3–18). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Brown, R.F., Bylund, C.L., Kline, N., De La Cruz, A., Solan, J., Kelvin, J., . . . Passik, S. (2009). Identifying and responding to depression in adult cancer patients: Evaluating the efficacy of a pilot communication skills training program for oncology nurses. Cancer Nursing, 32(3), E1–E7.

Bui, Q.U., Ostir, G.V., Kuo, Y.F., Freeman, J., & Goodwin, J.S. (2005). Relationship of depression to patient satisfaction: Findings from the barriers to breast cancer study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 89, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-004-1005-9

Carlson, L.E., & Bultz, B.D. (2004). Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: Making the case for economic analyses. Psycho-Oncology, 13, 837–849.

Carlson, L.E., Waller, A., & Mitchell, A.J. (2012). Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: Review and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1160–1177.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage.

Cuijpers, P., Donker, T., van Straten, A., Li, J., & Andersson, G. (2010). Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychological Medicine, 40, 1943–1957.

Dilworth, S., Higgins, I., Parker, V., Kelly, B., & Turner, J. (2014). Patient and health professional’s perceived barriers to the delivery of psychosocial care to adults with cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3474

Donovan, K.A., Grassi, L., McGinty, H.L., & Jacobsen, P.B. (2014). Validation of the Distress Thermometer worldwide: State of the science. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 241–250.

Estes, J.M., & Karten, C. (2014). Nursing expertise and the evaluation of psychosocial distress in patients with cancer and survivors. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 598–600.

Fallowfield, L., Ratcliffe, D., Jenkins, V., & Saul, J. (2001). Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 84, 1011–1015.

Fukui, S., Ogawa, K., Ohtsuka, M., & Fukui, N. (2009). Effect of communication skills training on nurses’ detection of patients’ distress and related factors after cancer diagnosis: A randomized study. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 1156–1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1429

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldin.

Granek, L., Nakash, O., Ariad, S., Chen, W., Birenstock-Cohen, S., Shapira, S., & Ben-David, M. (2017). From will to live to will to die: Oncologists, nurses and social workers identification of suicidality in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 3691–3702.

Granek, L., Nakash, O., Ben-David, M., Shapira, S., & Ariad, S. (2018a). Oncologists’, nurses’, and social workers’ strategies and barriers to identifying suicide risk in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4481

Granek, L., Nakash, O., Ben-David, M., Shapira, S., & Ariad, S. (2018b). Oncologists’ treatment responses to mental health distress in their cancer patients. Qualitative Health Research, 28, 1735–1745. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318786479

Güner, P., Hiçdurmaz, D., Kocaman Yıldırım, N., & İnci, F. (2018). Psychosocial care from the perspective of nurses working in oncology: A qualitative study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 34, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.03.005

Holland, J.C., & Alici, Y. (2010). Management of distress in cancer patients. Journal of Supportive Oncology, 8, 4–12.

Holland, J.C., & Bultz, B.D. (2007). The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 5, 3–7.

Institute of Medicine. (2008). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Kaneko, M., Ryu, S., Nishida, H., Tamasato, K., Shimodaira, Y., Nishimura, K., & Kume, M. (2013). Nurses’ recognition of the mental state of cancer patients and their own stress management—A study of Japanese cancer-care nurses. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1624–1629.

Kaul, S., Avila, J.C., Mutambudzi, M., Russell, H., Kirchhoff, A.C., & Schwartz, C.L. (2017). Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the national health interview survey. Cancer, 123, 869–878.

Kennard, B.D., Stewart, S.M., Olvera, R., Bawdon, R.E., Hailin, A.O., Lewis, C.P., & Winick, N.J. (2004). Nonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: Preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 11, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOCS.0000016267.21912.74

Lazenby, M. (2014). The international endorsement of US distress screening and psychosocial guidelines in oncology: A model for dissemination. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 12, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2014.0023

McDonald, M.V., Passik, S.D., Dugan, W., Rosenfeld, B., Theobald, D.E., & Edgerton, S. (1999). Nurses’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 26, 593–599.

Miyajima, K., Fujisawa, D., Hashiguchi, S., Shirahase, J., Mimura, M., Kashima, H., & Takeda, J. (2014). Symptoms overlooked in hospitalized cancer patients: Impact of concurrent symptoms on oversight [corrected] by nurses. Palliative and Supportive Care, 12, 95–100.

Musiello, T., Dixon, G., O’Connor, M., Cook, D., Miller, L., Petterson, A., . . . Johnson, C. (2017). A pilot study of routine screening for distress by a nurse and psychologist in an outpatient haematological oncology clinic. Applied Nursing Research, 33, 15–18.

Nakaguchi, T., Okuyama, T., Uchida, M., Ito, Y., Komatsu, H., Wada, M., & Akechi, T. (2013). Oncology nurses’ recognition of supportive care needs and symptoms of their patients undergoing chemotherapy. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 43, 369–376.

Nakash, O., & Alegría, M. (2013). Examination of the role of implicit clinical judgments during the mental health intake. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 645–654.

Nakash, O., Levav, I., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Andrade, L.H., Angermeyer, M.C., . . . Scott, K.M. (2014). Comorbidity of common mental disorders with cancer and their treatment gap: Findings from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 40–51.

Nakash, O., Liphshitz, I., Keinan-Boker, L., & Levav, I. (2013). The effect of cancer on suicide among elderly Holocaust survivors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 43, 290–295.

Nakash, O., & Nagar, M. (2018). Assessment of diagnostic information and quality of working alliance with clients diagnosed with personality disorders during the mental health intake. Journal of Mental Health, 27, 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294740

Nakash, O., Nagar, M., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2015). Clinical use of the DSM categorical diagnostic system during the mental health intake session. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76, e862–e869.

National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. (2013). National Consensus Project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (3rd ed.). Pittsburgh, PA: Author.

O’Donnell, E. (2013). The Distress Thermometer: A rapid and effective tool for the oncology social worker. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 26, 353–359.

Osborn, R.L., Demoncada, A.C., & Feuerstein, M. (2006). Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: Meta-analyses. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 36, 13–34. https://doi.org/10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L

Pehlivan, T., & Küçük, L. (2016). Skills of oncology nurses in diagnosing the psychosocial needs of the patients. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 9, 284–295.

Prieto, J.M., Blanch, J., Atala, J., Carreras, E., Rovira, M., Cirera, E., & Gastó, C. (2002). Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 1907–1917.

Sanjida, S., Janda, M., Kissane, D., Shaw, J., Pearson, S.A., DiSipio, T., & Couper, J. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of prescribing practices of antidepressants in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 25, 1002–1016. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4048

Singer, S., Das-Munshi, J., & Brähler, E. (2010). Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care—A meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 21, 925–930.

Söllner, W., DeVries, A., Steixner, E., Lukas, P., Sprinzl, G., Rumpold, G., & Maislinger, S. (2001). How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? British Journal of Cancer, 84, 179–185.

Tatrow, K., & Montgomery, G.H. (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9036-1

Turner, J., Mackenzie, L., Kelly, B., Clarke, D., Yates, P., & Aranda, S. (2018). Building psychosocial capacity through training of front-line health professionals to provide brief therapy: Lessons learned from the PROMPT study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26, 1105–1112.

Vitek, L., Rosenzweig, M.Q., & Stollings, S. (2007). Distress in patients with cancer: Definition, assessment, and suggested interventions. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.CJON.413-418

Walker, J., Postma, K., McHugh, G.S., Rush, R., Coyle, B., Strong, V., & Sharpe, M. (2007). Performance of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool for major depressive disorder in cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 83–91.

Werner, A., Stenner, C., & Schüz, J. (2012). Patient versus clinician symptom reporting: How accurate is the detection of distress in the oncologic after-care? Psycho-Oncology, 21, 818–826. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1975

Zebrack, B., Kayser, K., Sundstrom, L., Savas, S.A., Henrickson, C., Acquati, C., & Tamas, R.L. (2015). Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: An analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33, 1165–1170.

Zigmond, A.S., & Snaith, R.P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.