Understanding Nursing Workplace Violence Trends for Safer Clinical Oncology Settings

Background: Workplace violence (WPV) against nursing professionals by patients and visitors occurs frequently, and rates of WPV increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. All nursing teams, including oncology nursing professionals, are at risk for WPV and need current WPV-related information applicable to their clinical experiences.

Objectives: This overview aims to increase awareness of trends and personal safety issues related to clinical oncology nursing practice and provide strategies and resources to enhance personal safety in nursing practice.

Methods: This overview used literature reviews, publicly reported sources, other scholarly resources, and real-world examples to identify and synthesize WPV trends related to clinical nursing.

Findings: This overview’s findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the increased rate of WPV and subsequent harm to nursing staff victims. Oncology nursing professionals can implement best practices to reduce their risk of being harmed, and healthcare institutions can operationalize best practices by having systems and resources in place that prevent and mitigate WPV.

Jump to a section

Earn free contact hours: Click here to connect to the evaluation. Certified nurses can claim no more than 1 total ILNA point for this program. Up to 1 ILNA point may be applied to Nursing Practice OR Oncology Nursing Practice OR Professional Practice/Performance OR Roles of the APRN. See www.oncc.org for complete details on certification.

Workplace violence (WPV) is a form of aggression that is not new to healthcare settings worldwide. Since 2011, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020) has reported that healthcare workers are one of the most frequently harmed occupational groups, accounting for 73% of all violence-related nonfatal workplace injuries. As the front line of health care and the largest group of clinical workers, nursing personnel face a higher risk for WPV than those in other healthcare professions (Christensen et al., 2022). For example, one in four U.S. nurses reported being assaulted during the past year, translating to two assaulted nurses every hour (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2023a, 2023b; Carbajal, 2022). This trend includes oncology settings where nurses are frequently at risk for and exposed to WPV (Mojarad et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2022; Ying et al., 2020).

There are four kinds of WPV, and type 2 WPV, also known as client-on-worker violence, is the most common type seen in nursing. In the nursing context, type 2 WPV involves patients and visitors being violent toward the nursing staff (ANA, 2015; Chirico et al., 2022; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2020b). This type of WPV can range from verbal insults and threats to physical displays, physical contact, and even homicide (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 2017). The victims of these events experience physical and psychological harm. At the same time, healthcare institutions see consequences, including decreased nursing productivity and job satisfaction, higher nursing absences, nurse turnover, and poor patient outcomes (Christensen & Wilson, 2022).

Incidents of WPV in nursing were on the rise before the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 (Christensen et al., 2022; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), and these rates have since dramatically increased (American Hospital Association, 2022; Christensen, 2023a; Dyer, 2021). Although U.S. hospital injuries involving violence increased at rates of 5%–10% per year in the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a 24% increase from 2019 to 2020 after the onset of the pandemic (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.). In addition, among samples of more than 2,500 individuals from National Nurses United (2022), the largest nurse labor union in the United States, there was a 119% increase in nurse-reported incidents of WPV from March 2021 to March 2022. Even more alarming, because these trends reflect reported events, and WPV often goes unreported, WPV in nursing has likely occurred at much higher frequencies (ANA, 2023b; Christensen & Wilson, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to increased WPV by introducing new stressors to healthcare consumers and systems, including increased mental illness, burnout, and fatigue, along with scarce resources, pandemic regulations, and misinformation (Christensen, 2023a; Christensen et al., 2023; Crismon et al., 2021; Dyer, 2021). Although these factors and trends of WPV have been widely reported throughout all nursing settings, relatively few recent sources have examined and discussed these findings within oncology nursing clinical environments (Catania et al., 2022; Christensen, 2023b; Santos et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2022). It is likely that the prevalence and severity of pandemic-related WPV among oncology nurses have not been well established because nursing literature discussing WPV favors the highest-risk settings, such as emergency departments and mental health settings (Carbajal, 2022; Christensen et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2022). However, oncology nursing populations also have a high risk for WPV (Jia et al., 2022; Li et al., 2017), including in inpatient and ambulatory care settings, and can benefit from having current WPV-related information that is applicable to their clinical experiences to promote their safety.

Purpose

This overview of WPV aims to increase awareness of trends and personal safety issues applicable to clinical oncology nursing practice and to provide strategies and resources to enhance personal safety in nursing practice. To target oncology nursing practice, this overview of WPV includes a broader range of nursing and healthcare sources.

Methods

This overview explores WPV trends applicable to clinical nursing based on a literature review of the Scopus®, PubMed®, and CINAHL® databases; publicly reported sources about WPV (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, International Committee of the Red Cross, Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Nurses United); and other scholarly resources about verbal abuse and physical violence in U.S. healthcare settings. In addition, the overview includes national guidelines, recommendations, and best practices related to WPV from personal security experts and based on clinical experiences. Finally, with a focus on clinical oncology nursing practice, the overview includes real-world clinical oncology practice scenarios and recommendations for nurses to enhance their workplace safety based on experts in personal safety.

Findings

Violence Trends During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Most areas of the world saw increased rates of violent crime after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Sundberg et al., 2023). For example, firearm violence, mass shootings, and homicides increased (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2022; Matthay et al., 2022; Schleimer et al., 2022), as did domestic violence (Kourti et al., 2023), political violence (Bartusevičius et al., 2021), violence targeted at racial and ethnic groups (Bartusevičius et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2023), and occupational violence, including in healthcare settings (Anderson, 2022; Dopelt et al., 2022). During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, a sample of U.S. RNs (N = 373) reported experiencing physical violence (44%) and verbal abuse (68%) (Byon et al., 2021). This trend was echoed globally, with the Red Cross receiving reports during the first six months of the pandemic of more than 600 incidents of violence, harassment, or stigmatization targeted toward healthcare personnel, patients, and organizations (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020). Such rates of WPV were sustained as the COVID-19 pandemic continued. Within a large U.S. dataset (N = 26,174) of public health workers collected during the pandemic, one in three experienced WPV that affected their mental health, including 41% (n = 1,416) of nurses (Tiesman et al., 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified incivility and violence in health care (Porath, 2022; Ramzi et al., 2022). Some factors contributing to the increase included the added mental stress experienced by patients, visitors, and healthcare workers; inadequate healthcare resources; frequent changes in health policy and procedures; pandemic misinformation; and fatigue with following and upholding pandemic regulations (Chirico et al., 2022; Dopelt et al., 2022; Dyer, 2021). Pandemic conditions (e.g., social isolation) and stressors may have weakened community ties and workplace relationships (Porath, 2022), further setting the stage for inappropriate interactions with nursing professionals. Some examples of WPV in nursing at this time were harrowing, with global incidents of people who harassed, spat on, stalked, attacked, stabbed, tortured, and even killed nurses (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020; Kemper, 2022). However, the most frequent type of WPV nurses encountered was verbal insults and threats (Byon et al., 2021). Nurses often view verbal abuse as benign or part of the job. This can contribute to underreporting and apparent toleration of this behavior (Christensen & Wilson, 2022).

Violence Trends in Oncology Nursing

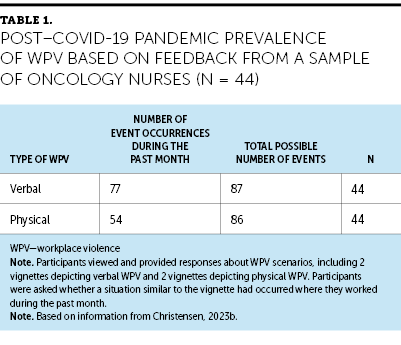

These WPV trends occur in ambulatory and inpatient oncology nursing settings and likely worsened during the pandemic. For example, in two studies conducted before the pandemic and that included oncology nurses, WPV victims reported incidence rates during the previous year of 44% and 66% for verbal abuse and 1.8% and 10.7% for physical violence (Chen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2017). In contrast, in a study conducted near the end of the third year of the pandemic, oncology nurses reported WPV occurrences during the past month at rates of 88.5% and 62.8% for verbal violence and physical violence, respectively (Christensen, 2023b) (see Table 1). Although this oncology example came from an isolated study and did not broadly represent clinical oncology settings, nursing staff have been more likely to experience WPV during the pandemic than other healthcare and public health workers (Chirico et al., 2022; Tiesman et al., 2023). Several real-world accounts from individual oncology nurses reinforce that WPV among oncology nurses increased during the pandemic. For example, one oncology nurse reported a substantial increase in verbal abuse within their nursing practice during the first two years of the pandemic (Greer, 2022). Figure 1 describes a seasoned oncology nurse’s experience with how the rise in WPV seen during the COVID-19 pandemic exposed many unhealthy workplace conditions related to WPV that nurses had endured throughout their nursing careers.

Several factors may have contributed to the potential rise in WPV among oncology nurses during the pandemic. First, oncology settings possess baseline patient and family stressors that may have been more pronounced during the pandemic. These factors include lengthy and tedious patient treatments, unstable patients, the likelihood of death, nurse–patient miscommunications, healthcare misinformation, and dissatisfaction with patient care or medical expenses (Chen et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2022). These existing factors that contribute to WPV likely heightened during the pandemic as other factors arose, such as COVID-19 pandemic regulations, scarcity of resources, and misinformation (Christensen, 2023a). For example, nurses were exposed to WPV during the pandemic because patients and relatives held them accountable for incomplete, delayed, and postponed care (Yesilbas & Baykal, 2021). Healthcare visitors and guests also victimized nurses for upholding hospital rules and other pandemic regulations (Yesilbas & Baykal, 2021). One oncology nurse described how their reinforcement of visitor policy restrictions was a frequent precursor to verbal abuse from angered patients with cancer and their visitors (Greer, 2022).

Outcomes of WPV

WPV leads to physical and psychological consequences for nursing victims. Minor to severe physical harms range from bruises and cuts to musculoskeletal and traumatic injuries. For example, one media report recounted a patient kicking a nurse in the jaw, pulling out her hair, and breaking her finger (Fello, 2022). In some cases, these physical injuries can even lead to death. In one study, oncology clinical workers were at greater risk than those in all other hospital departments for death related to WPV (Jia et al., 2022); however, this may have been because of the overall low count of fatalities in the study. Although the adverse outcomes of physical harm are significant, the psychological consequences of WPV can be just as damaging to the nurse’s health and ability to provide patient care (ANA, 2015; Ramzi et al., 2022). Oncology nurse victims of WPV have reported stress, fatigue, less concentration on the job, low sleep quality, burnout, and depression (Mojarad et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2021; Withers, 2022). These impacts can contribute to absenteeism from work, with one study reporting that 37.1% of nurses who experienced WPV were subsequently unable to work (Wang et al., 2023). Incidents experienced by nursing professionals drive the statistics reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics that suggest healthcare workers are the top group to miss workdays because of violence-related injuries (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.). The adverse outcomes of WPV contribute to job dissatisfaction in nursing and nurse intention to leave the job (Piotrowski et al., 2022). For example, the nurse with the pulled hair and broken finger stopped working altogether because of the emotional toll of the incident (Fello, 2022). These negative consequences can lead to mental health disorders that affect a nurse’s quality of life (Ramzi et al., 2022).

Mitigation Strategies for WPV

The rise in rates of WPV against healthcare workers has increased the interest of national healthcare policymakers in this issue, including politicians, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, ANA, and the American Hospital Association. In 2023, ANA (2023b) issued a call to action to stop tolerating WPV against nurses. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2022) issued a memorandum in November 2022 requiring all Medicare-certified healthcare facilities to provide training, policies, and procedures to protect their workforce and patients from WPV. Several national and state U.S. politicians and advocacy groups have worked to make WPV against healthcare workers a crime punishable by fines and jail time (American Hospital Association, 2022; Gooch & Plescia, 2022; Stone, 2022).

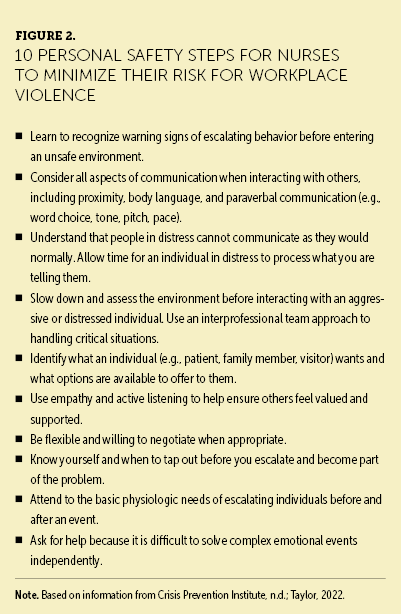

Beyond broad efforts from healthcare policymakers, perhaps the most effective actions to minimize WPV are implemented by local healthcare staff and institutions. Oncology nurses can implement several measures to increase the safety of their interactions with patients and visitors. For example, before interacting with patients and visitors, it is a best practice for nurses to understand the patient’s history and know whether they have acted disruptively before or whether there is any reason to suspect that they might misbehave. Upon entering the room, nurses can pay attention to the environment; for example, they can note the room’s exits, any trip hazards, patient and visitor behaviors, and objects that aggressors could use as weapons. When visiting with patients and visitors, nurses can be aware of their body language and proximity to patients and visitors while actively listening and paying attention to the body language of others. If it appears that someone’s behavior might escalate, the nurse can trust their intuition, call for help, and leave if the situation escalates or they have concerns (see Figure 2).

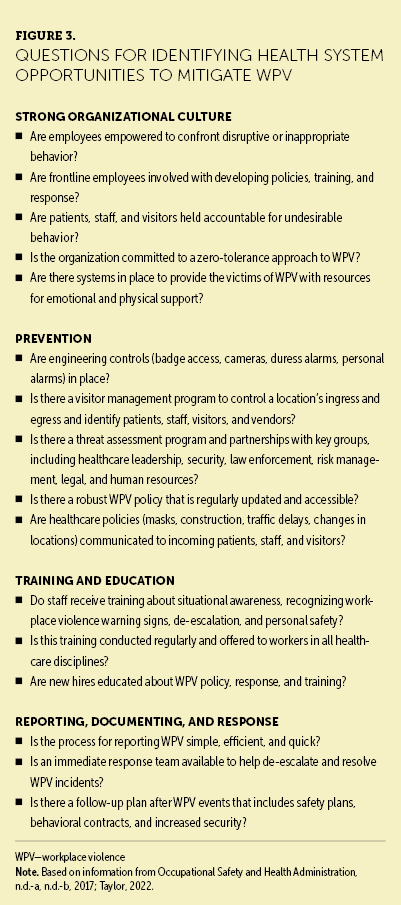

Some skills to increase safety when interacting with patients and visitors take time, practice, and institutional resources to master. Healthcare organizations can implement measures to reduce and mitigate WPV events. In keeping with recommendations from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (2020), one of the first steps healthcare employers can implement to protect their workers is establishing a zero-tolerance policy for WPV. They can build these policies by identifying opportunities to improve their organizational safety culture (see Figure 3), fostering a workplace culture that encourages nurse reporting of WPV, providing resources for victims, and investing in programs that promote practical skills and resources for workplace safety and patient de-escalation.

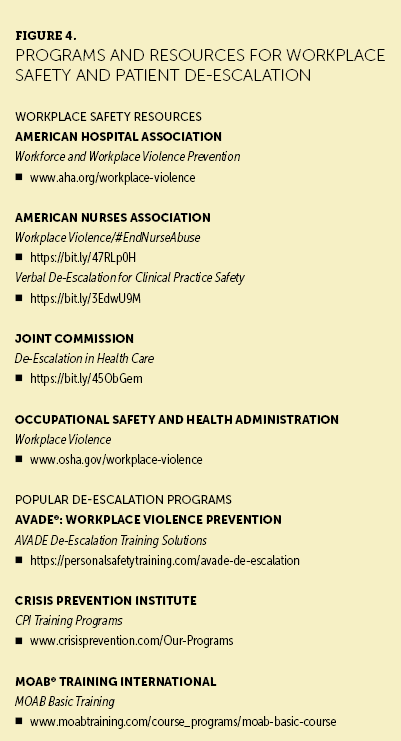

National programs and resources are available that foster workplace safety and help nurses learn and practice de-escalation (see Figure 4). Many organizations have implemented behavioral emergency response teams in which staff members are paged and arrive at the patient room for added support with de-escalation. Such programs have increased nurses’ skills and confidence in safely working with patients when they behave aggressively, improving nurse and patient outcomes (Christensen et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2022). For example, when collecting a real-world clinical oncology practice example for this overview, an oncology nurse described feeling flustered after being struck by her patient. She reported finding clarity in knowing she could call for help by activating a behavioral emergency response team. She shared how this group of skilled experts quickly took over to de-escalate the situation, promoting safety for the nurse and patient, and ultimately supporting this nurse in regaining her confidence after a traumatic event.

Discussion

WPV is prevalent among nursing professionals, which includes teams who care for patients with cancer. According to ANA (2023b), the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2020a), and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018), nursing is one of the highest-risk occupations for experiencing WPV. WPV against nurses worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by significant and lasting effects such as physical injuries, emotional harm, job dissatisfaction, and intention to leave the job (Piotrowski et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2021). This trend, in part, may be responsible for the substantial increase in nursing staff shortages and one in three nurses feeling emotionally unwell during the pandemic (American Nurses Foundation, 2021; Christensen et al., 2023).

The clinical environment for WPV also worsened throughout nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not as highly reported in oncology as in other clinical care settings, the accounts of pandemic-related WPV against oncology nurses are still concerning (Greer, 2022; Stone, 2022). Patients with cancer and their families experience unique challenges and stressors, which may have heightened WPV through the added stressors brought on and exacerbated by the pandemic. For example, some patients with cancer were delayed or disrupted in receiving lifesaving treatments because of limited healthcare resources, and many were vulnerable to being harmed by COVID-19 infection because of their cancer diagnosis and treatments (Momenimovahed et al., 2021). A common precursor to WPV-related behavior is a delay in care; patients and family members may blame clinical staff for failing to meet expectations (Alsharari et al., 2022). Patient fears (e.g., fear of death, fear of catching the coronavirus) also contribute to WPV (Byon et al., 2021). Patients with cancer and visitors also experienced added stress and other adverse impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic because of visitation restrictions (McCarthy et al., 2022), which can contribute to aggression and acting-out behaviors.

Implications for Nursing

WPV in healthcare facilities increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and is likely prevalent in oncology care settings. This trend is concerning for oncology nursing professionals because of the severe consequences that occur for the victims of WPV, including physical harm and long-lasting emotional trauma. Given the high prevalence of WPV against nurses and the significant impacts, WPV mitigation strategies in oncology nursing care settings are more critical now than ever.

Healthcare organizations can take protective measures for their nurses by identifying and addressing workplace safety needs (Ramzi et al., 2022). This effort may include providing resources to build healthcare workers’ confidence and skill at interacting safely with all patients and implementing systems that enhance coordination between nursing and security teams. Institutions that have made these investments have seen improved nurse confidence and skills for working with challenging patients and reduced WPV incidents (Christensen et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2022). For example, after one academic medical center noticed an increase in WPV events at its healthcare facilities, the center implemented a workplace safety program that included a behavioral emergency response team (Christensen et al., 2022). This program included broadly assessing the healthcare system to identify opportunities to improve workplace safety and using an interprofessional approach to develop and implement these safety measures. Nursing and security teams trained together and learned how to use resources for patient safety, including incorporating a behavioral emergency response system and routine rounding and communication among these teams.

Of note, oncology nurses can take individual actions to improve the safety of their workplace environment. Oncology nurses can better understand WPV trends and take measures to mitigate their risks. This effort can include being determined not to accept WPV as a regular part of the job, reporting when they have experienced any form of WPV, and advocating for policies that promote healthcare safety (ANA, 2023b).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic heightened the WPV already experienced by nursing professionals. Although based on limited sources, this overview suggests that WPV, as in any clinical healthcare setting, is an issue in the clinical oncology setting. Stressors of patients with cancer that can contribute to WPV may include arduous patient treatments, poor prognoses, nurse–patient miscommunications, healthcare misinformation, and stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the findings from this overview of WPV trends, outcomes, and mitigation approaches, oncology nurses can implement strategies to improve their personal safety in their clinical care environment. Healthcare institutions play a role in helping to make this happen by having systems and resources in place that prevent and mitigate WPV.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Barbara L. Wilson, PhD, for her critique of the first draft of the manuscript, and Ellen Carr, PhD, RN, AOCN®, for providing insight on the outline of topics for the manuscript.

About the Authors

Scott S. Christensen, PhD, MBA, APRN, ACNP-BC, is a senior nursing director and nurse scientist at the University of Utah Health Hospitals and Clinics and an adjunct assistant professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Utah; Chris Snyder is a retired chief of police at the South Salt Lake Police Department and a certified Crisis Prevention Institute senior instructor and chief of staff to the chief safety officer, both in the Department of Public Safety at the University of Utah; Eliza D. Parkin, DNP, APRN, FNP-C, is a clinical nurse in the bone marrow transfer unit in the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah; and Mary Jean Austria, MSN, RN, OCN®, is the director of the Magnet program at the University of Utah Health Hospitals and Clinics, all in Salt Lake City. The authors take full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Christensen can be reached at s.christensen@hsc.utah.edu, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted March 2023. Accepted May 18, 2023.)

References

Alsharari, A.F., Abu-Snieneh, H.M., Abuadas, F.H., Elsabagh, N.E., Althobaity, A., Alshammari, F.F., . . . Alatawi, S.S. (2022). Workplace violence towards emergency nurses: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Australasian Emergency Care, 25(1), 48–54.

American Hospital Association. (2022). Fact sheet: Health care workplace violence and intimidation, and the need for a federal legislative response. https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2022-06-07-fact-sheet-workplace-violenc…

American Nurses Association. (2015). Incivility, bullying, and workplace violence [Position statement]. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/officia…

American Nurses Association. (2023a). Workplace survey. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-sa…

American Nurses Association. (2023b). Workplace violence/#EndNurseAbuse. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/end-nurse…

American Nurses Foundation. (2021, October 13). Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses Survey Series: Mental health and wellness. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4a22b6/globalassets/docs/ancc/magnet/anf-…

Anderson, J. (2022). COVID-19 in the airline industry: The good, the bad, and the necessary. New Solutions, 32(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/10482911221101429

Bartusevičius, H., Bor, A., Jørgensen, F., & Petersen, M.B. (2021). The psychological burden of the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with antisystemic attitudes and political violence. Psychological Science, 32(9), 1391–1403. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211031847

Byon, H.D., Sagherian, K., Kim, Y., Lipscomb, J., Crandall, M., & Steege, L. (2021). Nurses’ experience with type II workplace violence and underreporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workplace Health and Safety, 70(9), 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/21650799211031233

Carbajal, E. (2022, September 8). 2 nurses assaulted every hour, Press Ganey analysis shows. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/nursing/2-nurses-assaulted-every-…

Catania, G., Pagnucci, N., Alvaro, R., Cicolini, G., Dal Molin, A., Lancia, L., . . . Watson, R. (2022). CN35 workplace violence against cancer nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A correlational-predictive study. Annals of Oncology, 33(Suppl. 7), S1363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.358

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2022). Workplace violence—Hospitals. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://go.cms.gov/3qNBU1Y

Chen, X., Lv, M., Wang, M., Wang, X., Liu, J., Zheng, N., & Liu, C. (2018). Incidence and risk factors of workplace violence against nurses in a Chinese top-level teaching hospital: A cross-sectional study. Applied Nursing Research, 40, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2018.01.003

Chirico, F., Afolabi, A.A., Ilesanmi, O.S., Nucera, G., Ferrari, G., Szarpak, L., . . . Magnavita, N. (2022). Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Health and Social Sciences, 7(1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.19204/2022/WRKP2

Christensen, S.S. (2023a, February 7). How nurses and administrators can respond to the prevalence of violence in health care. ONS Voice. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/how-nurses-and-administrators-can-…

Christensen, S.S. (2023b). Understanding nursing victim reactions, attitudes, and likelihood to report patient aggression: A mixed-methods design [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Utah.

Christensen, S.S., Lassche, M., Banks, D., Smith, G., & Inzunza, T.M. (2022). Reducing patient aggression through a nonviolent patient de-escalation program: A descriptive quality improvement process. Worldviews of Evidence-Based Nursing, 19(4), 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12540

Christensen, S.S., Nixon, T.L., Aguilar, R.L., Muhamedagic, Z., & Mahoney, K. (2023). Using participatory management to empower nurses to identify and prioritize the drivers of their burnout. International Journal of Healthcare Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2023.2190251

Christensen, S.S., & Wilson, B.L. (2022). Why nurses do not report patient aggression: A review and appraisal of the literature. Journal of Nursing Management, 60(6), 1759–1767. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13618

Crisis Prevention Institute. (n.d.). CPI training programs. https://www.crisisprevention.com/Our-Programs

Crismon, D., Mansfield, K.J., Hiatt, S.O., Christensen, S.S., & Cloyes, K.G. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on experiences and perceptions of nurse graduates. Journal of Professional Nursing, 37(5), 857–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.06.008

Dopelt, K., Davidovitch, N., Stupak, A., Ayun, R.B., Eltsufin, A.L., & Levy, C. (2022). Workplace violence against hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Implications for public health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084659

Dyer, O. (2021). US hospitals tighten security as violence against staff surges during pandemic. BMJ, 375, n2442. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2442

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2022). Active shooter incidents in the United States in 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-in-the-us-…

Fello, J. (2022, December 15). Nurse attacked by patient in Milwaukee hospital: ‘A street brawl that you would see in a movie’. WTMJ-TV Milwaukee. https://www.tmj4.com/news/local-news/nurse-attacked-by-patient-in-milwa…

Gooch, K., & Plescia, M. (2022, March 9). Lawmakers in these 6 states move to combat violence against healthcare workers. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/workforce/lawmakers-in-these-6-st…

Greer, M. (2022, February 7). Abuse can come from patients or peers. Here’s how to protect yourself and your colleagues. ONS Voice. https://bit.ly/3OTrrtI

International Committee of the Red Cross. (2020, August 18). 600 violent incidents recorded against health care providers, patients due to COVID-19. https://bit.ly/3PbNBZH

Jia, C., Han, Y., Lu, W., Li, R., Liu, W., & Jiang, J. (2022). Prevalence, characteristics, and consequences of verbal and physical violence against healthcare staff in Chinese hospitals during 2010–2020. Journal of Occupational Health, 64(1), e12341. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12341

Kemper, K.R. (2022, August 30). June 2022 saw 5 violent attacks in US hospitals. Security. https://www.securitymagazine.com/articles/98244-june-2022-saw-5-violent…

Kourti, A., Stavridou, A., Panagouli, E., Psaltopoulou, T., Spiliopoulou, C., Tsolia, M., . . . Tsitsika, A. (2023). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 24(2), 719–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690

Li, Z., Yan, C.-M., Shi, L., Mu, H.-T., Li, X., Li, A.-Q., . . . Mu, Y. (2017). Workplace violence against medical staff of Chinese children’s hospitals: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 12(6), e0179373. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179373

Lim, H., Lee, C.S., & Kim, C. (2023). COVID-19 pandemic and anti-Asian racism & violence in the 21st century. Race and Justice, 13(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/21533687221138963

Matthay, Z.A., Callcut, R.A., Kwok, A.M., Aarabi, S., Forrester, J.D., & Kornblith, L.Z. (2022). A parallel pandemic: Increased firearm injuries at five northern California trauma centers during the COVID-19 pandemic: An interrupted time-series analysis. Annals of Surgery, 275(5), e725–e727. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005334

McCarthy, M.C., Beamish, J., Bauld, C.M., Marks, I.R., Williams, T., Olsson, C.A., & De Luca, C.R. (2022). Parent perceptions of pediatric oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Australian study. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 69(2), e29400. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.29400

Mojarad, F.A., Jouybari, L., & Sanagoo, A. (2018). Rocky road ahead of nursing presence in the oncology care unit: A qualitative study. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 6(11), 2221–2227. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2018.426

Momenimovahed, Z., Salehiniya, H., Hadavandsiri, F., Allahqoli, L., Günther, V., & Alkatout, I. (2021). Psychological distress among cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic in the world: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682154

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2020a). Workplace violence prevention for nurses: Extent of the problem. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://cdc.gov/WPVHC/Nurses/Course/Slide/Unit1_6

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2020b). Workplace violence prevention for nurses: Types of workplace violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/WPVHC/Nurses/Course/Slide/Unit1_5

National Nurses United. (2022, April 14). National nurse survey reveals significant increases in unsafe staffing, workplace violence, and moral distress. https://bit.ly/3P9Z8Zw

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.-a). SEC. 5. Duties. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/oshact/section_5

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.-b). Workplace violence. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.osha.gov/workplace-violence

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2017). Enforcement procedures and scheduling for occupational exposure to workplace violence. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement/directives/CPL_02-…

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2020). Healthcare workplace violence. https://www.osha.gov/healthcare/workplace-violence

Piotrowski, A., Sygit-Kowalkowska, E., Boe, O., & Rawat, S. (2022). Resilience, occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intention to leave the organization among nurses and midwives during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6826. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116826

Porath, C. (2022, November 9). Frontline work when everyone is angry. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/11/frontline-work-when-everyone-is-angry

Ramzi, Z.S., Fatah, P.W., & Dalvandi, A. (2022). Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 896156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.896156

Santos, J.D., Meira, K.C., Coelho, J.C., Dantas, E.S.O., Oliveira, L.V.E., de Oliveira, J.S.A., . . . Pierin, A.M.G. (2021). Work-related violence and associated variables in oncology nursing professionals [Article in Portuguese]. Cien Saude Colet, 26(12), 5955–5966. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320212612.14942021

Schleimer, J.P., Pear, V.A., McCort, C.D., Shev, A.B., De Biasi, A., Tomsich, E., . . . Wintemute, G.J. (2022). Unemployment and crime in US cities during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Urban Health, 99(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00605-3

Stone, A. (2022, September 22). Workforce violence requires legislative support. ONS Voice. https://voice.ons.org/advocacy/workforce-violence-requires-legislative-…

Sundberg, K.W., Mitchell, L.M., & Levinson, D. (2023). Health, religiosity and hatred: A study of the impacts of COVID-19 on world Jewry. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(1), 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01692-5

Taylor, L. (Host). (2022, October 21). Violence in health care (No. 230) [Audio podcast episode]. In The Oncology Nursing Podcast. https://bit.ly/3PbikVJ

Thompson, S.L., Zurmehly, J., Bauldoff, G., & Rosselet, R. (2022). De-escalation training as part of a workplace violence prevention program. Journal of Nursing Administration, 52(4), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001135

Tiesman, H.M., Hendricks, S.A., Wiegand, D.M., Lopes-Cardozo, B., Rao, C.Y., Horter, L., . . . Byrkit, R. (2023). Workplace violence and the mental health of public health workers during COVID-19. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 64(3), 315–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.10.004

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. https://www.bls.gov/iif/data.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Occupational injuries and illnesses among registered nurses. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/occupational-injuries-and-ill…

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Factsheet: Workplace violence in healthcare, 2018. https://www.bls.gov/iif/factsheets/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.h…

Wang, T., Abrantes, A.C.M., & Liu, Y. (2023). Intensive care units nurses’ burnout, organizational commitment, turnover intention and hospital workplace violence: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Open, 10(2), 1102–1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1378

Withers, C. (2022). Factors contributing to nurse burnout in oncology [Undergraduate honors thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville]. ScholarWorks@UARK. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1179&context=…

Yesilbas, H., & Baykal, U. (2021). Causes of workplace violence against nurses from patients and their relatives: A qualitative study. Applied Nursing Research, 62, 151490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151490

Ying, L., Qingyue, Z., Yanxia, S., Dandan, G., & Mengqiu, H. (2020). Correlation analysis of psychological violence among nurses and job satisfaction in oncology department. Tianjin Journal of Nursing, 28(3), 287. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9143.2020.03.009