Breast and Colon Cancer Survivors’ Expectations About Physical Activity for Improving Survival

Purpose/Objectives: To compare physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival with traditional physical activity outcome expectations in breast and colon cancer survivors.

Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Setting: Canada and the United States.

Sample: 146 participants.

Methods: Self-reported survey instruments and height and weight measurement. The online survey was completed once by each participant.

Main Research Variables: Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, Multidimensional Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale (MOEES), and an item assessing physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival.

Findings: Paired sample t tests indicated that the mean score for the physical subscale of the MOEES was significantly higher than the mean score on the physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival variable (p < 0.001). Multiple regression analyses indicated that physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival explained 4.8% of the variance in physical activity (p = 0.011).

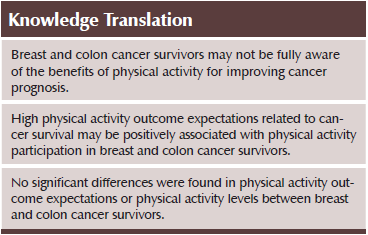

Conclusions: Findings from the current study suggest that, among breast and colon cancer survivors, outcome expectations related to cancer survival may influence physical activity levels and may not be as realized as traditional outcome expectations.

Implications for Nursing: Oncology nurses should familiarize themselves with the guidelines and benefits of physical activity for survivors so they can provide guidance and support to patients.

Jump to a section

Physical activity has become increasingly recognized for its role in improving health-related quality-of-life concerns (e.g., fatigue, pain, mood and sleep disturbances, cancer-specific issues) in cancer survivors, as well as improving fatigue and physical, role, and social functioning in on-treatment survivors (Garcia & Thomson, 2014; Mishra, Scherer, Geigle, et al., 2012; Mishra, Scherer, Snyder, et al., 2012). The potential supportive care role that physical activity may play in the lives of cancer survivors has led to the development of physical activity guidelines and recommendations by the American Cancer Society (ACS) (Rock et al., 2012) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (Schmitz et al., 2010); such guidelines and recommendations indicate that physical activity is safe for cancer survivors and that survivors should regularly engage in physical activity to maximize benefits to their quality of life and health.

Research has suggested that regular physical activity after cancer diagnosis may also be significant in improving survival outcomes in survivors of breast and colon cancer (Lemanne, Cassileth, & Gubili, 2013). For example, epidemiologic evidence from large-scale cohort studies has shown that participation in regular physical activity after diagnosis can result in as much as a 50% reduction in the risk of cancer mortality in breast and colon cancer survivors (Ballard-Barbash et al., 2012; Clague & Bernstein, 2012). Specifically, walking the equivalent of three and six hours per week after diagnosis has been found to be associated with a significant decrease in the risk of breast and colon cancer mortality, respectively (Lemanne et al., 2013). In addition, several randomized, controlled trials have provided evidence of potential mechanisms that link physical activity to reduced cancer mortality, including improving circulating levels of insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), IGF–1 binding proteins, and C–reactive protein and increasing natural killer cell cytotoxicity (Ballard-Barbash et al., 2012). Therefore, although not conclusive, the research to date suggests that physical activity after breast or colon cancer diagnosis could substantially improve cancer-specific survival outcomes.

Given the many possible benefits associated with physical activity among cancer survivors, researchers have attempted to understand motivational factors associated with physical activity behavior in this population. Social cognitive theory (SCT) has been previously used in regard to cancer survivors as a theory of health behavior change to understand factors that influence physical activity motivation (Pinto & Ciccolo, 2011). According to SCT in the physical activity context, positive physical activity outcome expectations increase the likelihood of future physical activity participation (Bandura, 1986; Wójcicki, White, & McAuley, 2009). In addition, physical activity intervention studies of patients with cancer (Perkins, Waters, Baum, & Basen-Engquist, 2009) and other populations (Ginis et al., 2011) suggest that positive changes in outcome expectations may result in increases in physical activity levels.

Despite evidence that supports the potential protective effect of physical activity on breast and colon cancer survival outcomes, how well this information has been disseminated to breast and colon cancer survivors is unclear. However, according to SCT, positive outcome expectations about the role of physical activity in improving survival times after breast or colon cancer could possibly serve as a source of physical activity motivation for cancer survivors. Research also suggests that the majority of cancer survivors seek complementary and alternative therapies during and after cancer treatment as a means of maintaining hope and self-control over cancer-related outcomes (De Lemos, 2005). Consequently, if cancer survivors were to realize the potential benefits of physical activity on survival outcomes, they may be more likely to embrace physical activity as an additional means of taking control and preserving hope during the cancer experience.

The primary purpose of this study was to compare physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival with traditional physical activity outcome expectations, as outlined by SCT, in breast and colon cancer survivors. Secondary purposes were to (a) assess the relationship between physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival and physical activity participation and (b) make comparisons between these relationships based on tumor type (i.e., breast cancer versus colon cancer).

Methods

The current study was approved by the research ethics board of Nipissing University in North Bay, Ontario, Canada, and informed consent was waived. Data were collected from June 2012 to February 2013. Study participants were recruited through advertisements posted on social media and discussion boards for online cancer survivor support groups. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18 years or older and having been diagnosed with breast or colon cancer during the past 10 years. The advertisements included a brief description of the study with a link to the online survey.

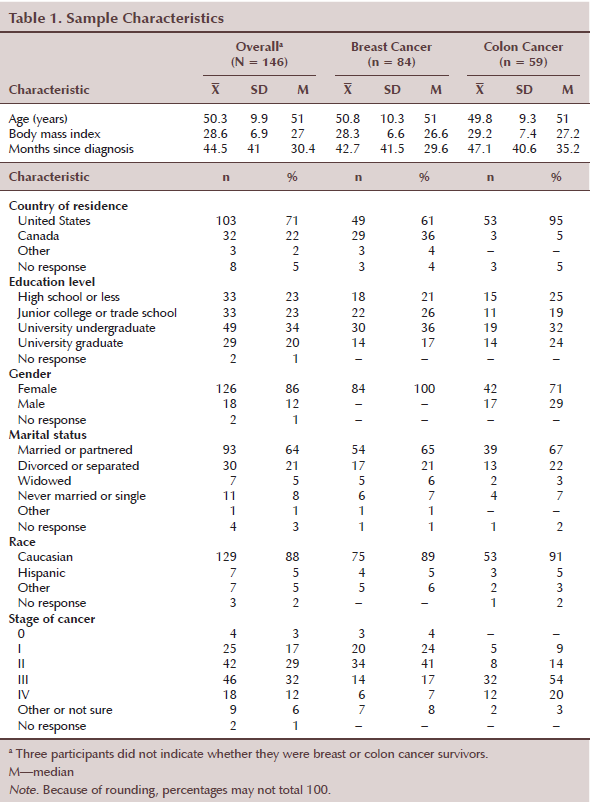

In all, 178 individuals initiated the study, and 32 were excluded because of substantial missing data (greater than 15%). Of the 146 participants included in the analyses, 12 had minor missing data (greater than 15% per scale) on the outcome expectations scales. Missing data were handled by averaging the available items of the subscale for the individual, and then substituting this mean for the missing data point. This method of handling missing data is considered reasonable if internal consistency is high (i.e., Cronbach alpha of greater than 0.7) and if the items that are averaged represent a single, unidimensional domain (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Participant details, including demographic and disease-related information, are available in Table 1.

Instrumentation

Physical activity: Physical activity was assessed using a modified version of the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) (Godin & Shephard, 1985). Participants were asked to report the number and duration of physical activity sessions they had completed in a typical week during the past month. Moderate-intensity physical activity and vigorous-intensity physical activity were reported separately. Items assessed participants’ average weekly minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, average weekly minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity, and combined average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity. The GLTEQ has been found to indicate adequate construct validity when compared to accelerometery (r = 0.45, p < 0.01) (Miller, Freedson, & Kline, 1994).

Physical activity outcome expectations: Physical activity outcome expectations were determined by the Multidimensional Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale (MOEES) (Wójcicki et al., 2009). The MOEES includes three subscales with items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The six-item physical subscale (range = 6–30) taps into expectations about physical outcomes as a result of physical activity. Items within the physical subscale are “physical activity will improve my ability to perform daily activities”; “physical activity will improve my overall body functioning”; “physical activity will strengthen my bones”; “physical activity will increase my muscle strength”; “physical activity will aid in weight control”; and “physical activity will improve the functioning of my cardiovascular system.” Internal consistency for the physical subscale in the current study was acceptable, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.79. The four-item social subscale (range = 4–20) reflects beliefs about the role of physical activity in providing opportunities for socialization and social approval. Items within the social subscale are “physical activity will improve my social standing”; “physical activity will make me more at ease with people”; “physical activity will provide companionship”; and “physical activity will increase my acceptance by others.” In the current study, internal consistency for the social subscale was found to be good, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.85. The five-item self-evaluative subscale (range = 5–25) captures expectations about physical activity for improving self-worth and satisfaction. Items within the self-evaluative subscale are “physical activity will help manage stress”; “physical activity will improve my mood”; “physical activity will improve my psychological state”; “physical activity will increase my mental alertness”; and “physical activity will give me a sense of personal accomplishment.” Internal consistency for the self-evaluative subscale in the current sample was found to be good, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.87. The MOEES has been found to have good internal consistency, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.81–0.84. It has also been found to have acceptable factorial validity by demonstrating excellent model fit (root mean square of approximation = 0.5, 90% confidence interval [0.03, 0.06], comparative fit index = 0.97) and good construct validity by indicating significant correlations between being physically active and physical (r = 0.21, p < 0.001) and self-evaluative (r = 0.2, p < 0.001) outcome expectations (Wójcicki et al., 2009). For the purposes of this study, the current authors have presented the total and mean scores of the three subscales.

Physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival: Physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival were assessed by an item similar in format to items on the MOEES. For this item, participants were asked to respond to the following statement: “Physical activity will reduce my risk of dying from cancer.” They were asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with the statement using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Based on items from the MOEES, this item was created by the current authors who independently evaluated the item for face validity prior to beginning the study.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS®, version 22.0. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to determine differences between breast and colon cancer survivors regarding physical activity (using the average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity variable), the subscales of the MOEES, and physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival. Paired sample t tests were used to identify differences between the mean on the physical subscale of the MOEES and physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival. Bivariate correlations using Pearson product-moment correlations among physical activity (using the average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity variable), the subscales of the MOEES, and physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival were determined. A multiple regression analysis with average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity variable as the criterion and physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival as the predictor was conducted using cancer type (i.e., breast cancer versus colon cancer) as a moderator.

Results

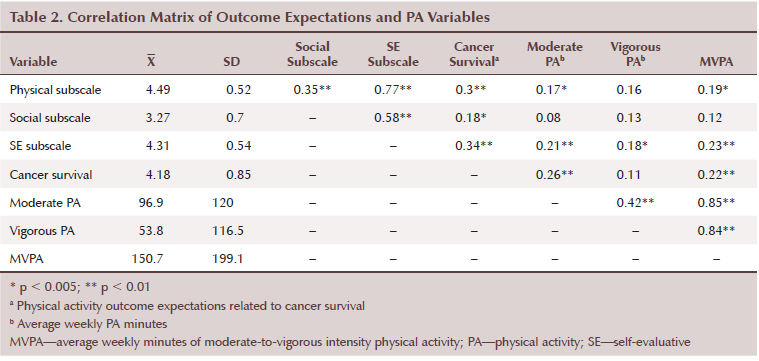

Results of the MANOVA indicated that no statistically significant differences were observed between breast and colon cancer survivors regarding physical activity variables, the MOEES, or physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival (F [5, 137] = 1.213, p = 0.307; Wilk’s lambda = 0.958, eta-squared = 0.04). When testing for differences in scores for physical activity outcome expectations, significant differences were found between scores for the physical subscale (mean = 4.49, SD = 0.52) and the physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival variable (mean = 4.18, SD = 0.85; t [145] = 4.35, p < 0.001). Results of the bivariate correlations between physical activity variables and outcome expectations variables are displayed in Table 2. Physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival explained 4.8% of the variance in average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (beta = 0.22, t [141] = 2.57, p = 0.011) with type of cancer (i.e., breast cancer versus colon cancer) not contributing as a significant moderator in the model (beta = –0.02, t [141] = –0.222, p = 0.825).

The analyses were repeated with the stage IV participants (n = 18) excluded because their responses to physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival could be significantly different than those of other cancer survivors because of their low survival rate. However, the results of these analyses were not substantially different from those performed with the entire sample, so only the analyses from the full dataset are presented.

Discussion

As hypothesized, participants indicated significantly lower outcome expectations for physical activity related to cancer survival compared to scores on the physical subscale. This finding suggests that participants were less likely to think that physical activity could reduce breast and colon cancer mortality compared to its ability to improve traditional physical outcome expectations (e.g., improving cardiovascular system or ability to perform daily activities). Similarly, a survey of colorectal cancer survivors (N = 560) found that only about 41% of participants believed that physical activity would reduce the risk of their cancer coming back, making it the least endorsed out of nine potential physical activity benefits (Speed-Andrews et al., 2014). In addition, past surveys eliciting perceived beliefs of physical activity have indicated that survivors list benefits such as improved health, weight loss, and feeling better most frequently, whereas survival benefits are rarely, if ever, mentioned (Karvinen, Raedeke, Arastu, & Allison, 2011; Vallance, Lavallee, Culos-Reed, & Trudeau, 2012). Breast and colon cancer survivors may not fully recognize the potential survival benefits of physical activity, which suggests a need for better dissemination of information from the scientific literature.

The positive correlation between physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival and physical activity level was as hypothesized and consistent with previous research that examined a similar relationship in colorectal cancer survivors (Speed-Andrews et al., 2014). Although determining causality is difficult because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, individuals having positive outcome expectations about physical activity and, therefore, a greater likelihood of future physical activity participation is logical and in line with SCT (Bandura, 1986). This finding further highlights the need for dissemination of information concerning the potential of physical activity to possibly improve survival outcomes for breast and colon cancer survivors. This dissemination of information could not only help to improve the physical activity rates of breast and colon cancer survivors, but also offer to cancer survivors a means of providing control and hope and serve as a coping mechanism and a way of improving distress (Olver, 2012).

No significant differences were found between breast and colon cancer survivors on any of the outcome measures. This finding was unexpected, given that breast cancer receives proportionately more advocacy and media attention compared to other cancers (Williamson, Jones, & Hocken, 2011). Consequently, the current authors expected that breast cancer survivors would have received more information about the role of physical activity in cancer survivorship, as well as additional opportunities for support. However, the finding that breast cancer survivors were not any more physically active than colon cancer survivors, as well as that the two groups of survivors did not differ in terms of physical activity outcome expectations, was surprising.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study’s strengths and limitations must be acknowledged. This study was one of the first to explore the extent to which breast and colon cancer survivors understand research that supports the role of physical activity in improving cancer survival outcomes, as well as how their knowledge affects physical activity rates. A better understanding of these relationships could guide future physical activity intervention strategies for breast and colon cancer survivors.

The main limitation of the current study is the possibility that users of social media and online cancer support groups are not fully representative of the general population of breast and colon cancer survivors. For example, the sample in the current study is primarily Caucasian and, on average, highly educated and several years into survivorship. Survivors who are more physically active may have self-selected participation in the study, creating a response bias. In addition, the measure for physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival was created by the current authors and only minimally assessed for validity and reliability. Interpreting causal relationships between variables also was not possible because of the cross-sectional nature of the study.

Implications for Nursing and Conclusions

The findings from this study have several implications for nursing practice and patient education. Oncology nurses must familiarize themselves with the potential benefits of physical activity for cancer survivors so they can share that information with patients. Research suggests that although many oncology nurses view physical activity as a favorable supportive care strategy for cancer survivors, they may not fully recognize the potential survival benefits and instead focus only on other benefits (e.g., improved quality of life, reduced risk of other chronic diseases) (Karvinen, McGourty, Parent, & Walker, 2012). If oncology nurses are able to fully recognize all of the benefits of physical activity for cancer survivors, they could better convey this information to patients, which, in turn, may lead to higher physical activity participation rates.

In addition, given that many breast and colon cancer survivors do not participate sufficiently in physical activity, oncology nurses may be wise to also provide physical activity guidance and support so more survivors can enjoy the numerous benefits of an active lifestyle. In surveys of cancer survivors, the majority of respondents indicated having a strong interest in receiving physical activity counseling and support, suggesting that patients are eager to receive more information about leading an active lifestyle (Karvinen et al., 2011; McGowan et al., 2013; Tyrrell, Keats, & Blanchard, 2014; Vallance, Lavallee, Culos-Reed, & Trudeau, 2013).

Oncology nurses also can become further educated about the role of physical activity in cancer survivorship. For example, the Oncology Nursing Society offers educational opportunities for its membership, such as the Get Up, Get Moving campaign, as well as an online course that focuses on physical activity for cancer survivors. Several free full-text articles are available that provide specific information about physical activity and breast (Eyigor & Kanyilmaz, 2014) and colorectal (Des Guetz et al., 2013) cancer survivor outcomes. In addition, oncology nurses can consult the ACS’s (Rock et al., 2012) or ACSM’s (Schmitz et al., 2010) physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors to provide optimal physical activity guidance and support to cancer survivors.

Through this study, the current authors found evidence that physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival were lower than other physical outcome expectations, suggesting that breast and colon cancer survivors may not be aware of the benefits of physical activity for improving cancer prognosis. However, high physical activity outcome expectations related to cancer survival appeared to be positively associated with physical activity participation. Based on these findings, better dissemination of information concerning the benefits of physical activity for improving cancer prognosis outcomes may be needed.

References

Ballard-Barbash, R., Friedenreich, C.M., Courneya, K.S., Siddiqi, S.M., McTiernan, A., & Alfano, C.M. (2012). Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 104, 815–840. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs207

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive view. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Clague, J., & Bernstein, L. (2012). Physical activity and cancer. Current Oncology Reports, 14, 550–558. doi:10.1007/s11912-012-0265-5

De Lemos, M.L. (2005). Pharmacist’s role in meeting the psychosocial needs of cancer patients using complementary therapy. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 204–210. doi:10.1002/pon.836

Des Guetz, G., Uzzan, B., Bouillet, T., Nicolas, P., Chouahnia, K., Zelek, L., & Morere, J.F. (2013). Impact of physical activity on cancer-specific and overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2013, 340851. doi:10.1155/2013/340851

Eyigor, S., & Kanyilmaz, S. (2014). Exercise in patients coping with breast cancer: An overview. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5, 406–411. doi:10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.406

Garcia, D.O., & Thomson, C.A. (2014). Physical activity and cancer survivorship. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 29, 768–779. doi:10.1177/0884533614551969

Ginis, K.A., Latimer, A.E., Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K.P., Bassett, R.L., Wolfe, D.L., & Hanna, S.E. (2011). Determinants of physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: A test of social cognitive theory. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 42, 127–133. doi:10.1007/s12160-011-9278-9

Godin, G., & Shephard, R.J. (1985). A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 10, 141–146.

Karvinen, K.H., McGourty, S., Parent, T., & Walker, P.R. (2012). Physical activity promotion among oncology nurses. Cancer Nursing, 35, E41–E48. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822d9081

Karvinen, K.H., Raedeke, T.D., Arastu, H., & Allison, R.R. (2011). Exercise programming and counseling preferences of breast cancer survivors during or after radiation therapy. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, E326–E334. doi:10.1188/11.ONF.E326-E334

Lemanne, D., Cassileth, B., & Gubili, J. (2013). The role of physical activity in cancer prevention, treatment, recovery, and survivorship. Oncology, 27, 580–585.

McGowan, E.L., Speed-Andrews, A.E., Blanchard, C.M., Rhodes, R.E., Friedenreich, C.M., Culos-Reed, S.N., & Courneya, K.S. (2013). Physical activity preferences among a population-based sample of colorectal cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, 44–52. doi:10.1188/13.ONF.44-52

Miller, D.J., Freedson, P.S., & Kline, G.M. (1994). Comparison of activity levels using the Caltrac accelerometer and five questionnaires. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 26, 376–382. doi:10.1249/00005768-199403000-00016

Mishra, S.I., Scherer, R.W., Geigle, P.M., Berlanstein, D.R., Topaloglu, O., Gotay, C.C., & Snyder, C. (2012). Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD007566. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2

Mishra, S.I., Scherer, R.W., Snyder, C., Geigle, P.M., Berlanstein, D.R., & Topaloglu, O. (2012). Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD008465. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008465.pub2

Olver, I.N. (2012). Evolving definitions of hope in oncology. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 6, 236–241. doi:10.1097/spc.0b013e3283528d0c

Perkins, H.Y., Waters, A.J., Baum, G.P., & Basen-Engquist, K.M. (2009). Outcome expectations, expectancy accessibility, and exercise in endometrial cancer survivors. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31, 776–785.

Pinto, B.M., & Ciccolo, J.T. (2011). Physical activity motivation and cancer survivorship. Recent Results in Cancer Research, 186, 367–387. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_16

Rock, C.L., Doyle, C., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Meyerhardt, J., Courneya, K.S., Schwartz, A.L., . . . Gansler, T. (2012). Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 62, 243–274. doi:10.3322/caac.21142

Schafer, J.L., & Graham, J.W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.147

Schmitz, K.H., Courneya, K.S., Matthews, C., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Galvão, D.A., Pinto, B.M., . . . Schwartz, A.L. (2010). American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42, 1409–1426. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112

Speed-Andrews, A.E., McGowan, E.L., Rhodes, R.E., Blanchard, C.M., Culos-Reed, S.N., Friedenreich, C.M., & Courneya, K.S. (2014). Identification and evaluation of the salient physical activity beliefs of colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 37, 14–22. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182813972

Tyrrell, A., Keats, M., & Blanchard, C. (2014). The physical activity preferences of gynecologic cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 461–469. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.461-469

Vallance, J., Lavallee, C., Culos-Reed, N., & Trudeau, M. (2013). Rural and small town breast cancer survivors’ preferences for physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 522–528. doi:10.1007/s12529-012-9264-z

Vallance, J.K., Lavallee, C., Culos-Reed, N.S., & Trudeau, M.G. (2012). Predictors of physical activity among rural and small town breast cancer survivors: An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 17, 685–697. doi:10.1080/13548506.2012.659745

Williamson, J.M., Jones, I.H., & Hocken, D.B. (2011). How does the media profile of cancer compare with prevalence? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 93, 9–12.

Wójcicki, T.R., White, S.M., & McAuley, E. (2009). Assessing outcome expectations in older adults: The Multidimensional Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 64B, 33–40. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn032

About the Author(s)

Kristina Karvinen, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Physical and Health Education at Nipissing University in North Bay, Ontario, and Jeff Vallance, PhD, is an associate professor in the Faculty of Health Disciplines at Athabasca University in Athabasca, Alberta, both in Canada. Vallance is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program and Alberta Innovates. Karvinen can be reached at kristinak@nipissingu.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted January 2015. Accepted for publication March 31, 2015.)