Hairy Cell Leukemia and Bone Pain

Hairy cell leukemia is a relatively rare but distinct B-cell lympho-proliferative disorder of the blood, bone marrow, and spleen that accounts for only 2% of all adult leukemia cases. The median age at presentation is 50–55 years, with a 4:1 male to female predominance. Although considered uncommon, a number of unusual clinical presentations have been noted in the literature, including the presence of peripheral lymphadenopathy, lytic bone lesions, skin involvement, organ involvement, and central nervous system involvement. Unlike the clinical management of other hematologic malignancies, no current system is used to stage hairy cell leukemia.

Jump to a section

A 70-year-old woman named Mrs. P was diagnosed with hairy cell leukemia in 2001. She was treated with chemotherapy (cladribine [Leustatin®]) at the time of presentation and again at relapse in 2005 and 2009. With each relapse, her leukemia responded to chemotherapy and she achieved remission. Three years into her last remission, Mrs. P presented to a follow-up appointment with complaints of hip and back pain. She had been in a motor vehicle accident three months earlier and was experiencing mild musculoskeletal pain. She was seeing her general practitioner and a chiropractor on a regular basis and taking over-the-counter analgesia for pain. No further intervention was deemed necessary at the time.

Three months later, with her disease still in remission, Mrs. P experienced severe back pain with tenderness on vertebral palpation. She had limited mobility and had lost 6 kg since last follow-up. She was not eating well because she found meal preparation painful and had lost interest in her everyday activities. Her blood workup reported a normal white blood count, mild neutropenia and hemoglobin, and platelets slightly less than normal. To better assess her pain, plain film x-rays were performed which showed subtle displaced rib fractures in keeping with her reported trauma. She was started on calcium and vitamin D while awaiting additional investigation. Bone mineral density showed osteoporosis and she was at high risk for fracture based on the following risk factors: female gender, advanced age, positive family history of osteoporosis and fractures, underlying hematologic malignancy, and having been a previous smoker.

Despite being started on bisphosphonate therapy to strengthen her bones, little improvement was noted in her symptoms. A bone scan showed multiple areas of lucency throughout the pelvis and bilateral proximal femur (right greater than left) in keeping with metastatic disease. Her biochemistry panel was normal, and no detectable monoclonal protein or free light chain disease was detectable. A bone marrow biopsy was negative for the presence of multiple myeloma or malignancy other than her known hairy cell leukemia, so computed tomography (CT) scans were used to rule out the presence of a second malignancy. Surprisingly, widespread abdominal lymphadenopathy was found, with the largest retroperitoneal node measuring 4.4 cm x 2.1 cm. At this point, Mrs. P was admitted to hospital in severe pain crisis. She was bedridden and experiencing severe anxiety and panic attacks because of her physical deterioration. A consult for psychiatry was initiated. CT scans revealed multiple lytic lesions in the pelvis and proximal aspect of each femur and throughout the lumbar/thoracic spine and ribs, consistent with widespread metastatic disease. Multiple thoracic compression fractures were found that were thought to be pathological in nature. Mrs. P had surgical repair of her right hip (pinning and fixation), and a biopsy of the right hip confirmed the presence of only hairy cell leukemia. Mrs. P was started on chemotherapy for her relapsed disease and received palliative radiotherapy to her right hip and proximal femur and later to her spine (T7–L1).

Mrs. P’s hospitalization and recovery were complicated. Her anxiety and depression made it difficult for staff to engage her in rehabilitation and the presence and fear of severe pain made mobilization difficult. She was assessed by psychiatric staff and the pain management services and started on an antidepressant and narcotics. She was fitted with a back brace and bilateral ankle braces to combat foot drop and slowly began ambulating with a walker. Two years later, Mrs. P is back in remission, has tapered off all analgesia, and is ambulating without assistance. She has returned to her previous level of activity and reports good quality of life and well-being.

Literature Review

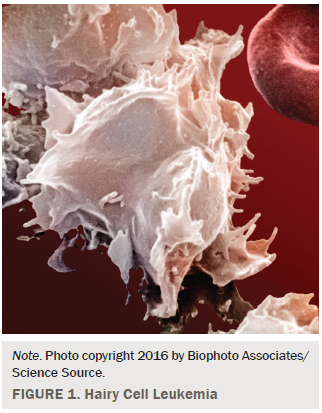

Hairy cell leukemia is a relatively rare but distinct B-cell lympho-proliferative disorder of the blood, bone marrow, and spleen that accounts for only 2% of all adult leukemia cases (Bouroncle, 1994). The median age at presentation is 50–55 years, with a 4:1 male to female predominance noted in the literature (Hoffman, 2006). Because of its distinct immunophenotypic profile (CD 19, CD20 [bright], CD 22 bright, 11c bright, CD 25, CD 103 bright, FMC7), hairy cell leukemia can be diagnosed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood in 92% of patients, with the remaining cases confirmed by a bone marrow biopsy that shows marrow replacement by reticulin fibrosis (Greer et al., 2014). Interestingly, the marrow aspirate often is dry because of marrow replacement (Gray, Rutherford, Bonin, Patterson, & Lopez, 2013). A review of the peripheral blood smear also will reveal leukemic cells with characteristic cytoplasmic projections, which appear “hair-like,” thus the name (Grever, 2010) (see Figure 1). Classical hairy cell leukemia has been linked with the BRAF v600E genetic mutation, which may assist clinicians with diagnosis and may lead to a potential target for therapy (Greer et al., 2014).

Individuals with hairy cell leukemia usually present with weakness and fatigue, and complications related to cytopenia and splenomegaly (Grever, 2010). Splenomegaly is a prominent clinical feature, present in 90% of all cases of hairy cell leukemia, but the absence of splenomegaly should not confuse or mislead clinicians from the diagnosis (Greer et al., 2014; Venkatesan et al., 2014). At presentation, hairy cell leukemia is marked by the presence of pancytopenia in more than half of cases, severe monocytopenia, and hepatomegaly, but lymphadenopathy is usually absent (Grever, 2010; Hoffman, 2006). Typical constitutional B symptoms found in other leukemia and lymphomas, such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, and anorexia, are considered uncommon but may be present in 20%–35% of patients (Greer et al., 2014). Pancytopenia in hairy cell leukemia is multifactorial primarily related to splenomegaly and its sequelae as well as bone marrow replacement by hairy cells and reticulin fibrosis (Forconi, 2011).

Although considered uncommon, a number of unusual clinical presentations have been noted in the literature, including the presence of peripheral lymphadenopathy, lytic bone lesions, skin involvement, organ involvement, and central nervous system involvement (Grever, 2010). Unlike the clinical management of other hematologic malignancies, no current system is used to stage hairy cell leukemia.

When hairy cell leukemia was introduced into the medical literature 50 years ago, the median survival at diagnosis was documented as only four years (Grever, 2010). Infectious complications were a frequent and major cause of death for patients and thought to be related to neutropenia, monocytopenia, monocyte dysfunction and impaired neutrophil microbicidal function, and natural killer cell depression (Bouroncle, 1994; Hoffman, 2006; Janckila, Wallace, & Yam, 1982). Initial treatment of hairy cell leukemia was with splenectomy, but improvements in systemic treatment options have made hairy cell leukemia a chronic and treatable disease for most, with infection rates markedly improved. A third of patients will develop an infection during the course of their disease, and overall prognosis has markedly improved (Damaj et al., 2009).

In addition to infection, complications of hairy cell leukemia include autoimmune disorders and an increased risk of second malignancies (Grever, 2010; Pemmaraju, Gill, & Krause, 2015). Hairy cell leukemia is highly responsive to chemotherapy with first-line monotherapy with a purine nucleoside analog (pentostatin [Nipent®] or cladribine), which can induce response rates of 75%–90% (Greer et al., 2014). Remission rates often are long lived, but the rate of relapse in hairy cell leukemia is 30%–40% (Grever, 2010). Goodman, Burian, and Koziol (2003) found that, depending on the duration and quality of the initial response, patients in relapse may be retreated with cladribine and achieve a second complete remission in 75% of cases. There also does not appear to be cross-resistance between nucleoside analogs, which increases treatment options for clinicians. Second-line therapy with the monoclonal antibody rituximab (Rituxan®) can produce response rates in 80% of patients and lead to durable remission rates, and is used in combination therapy with nucleoside analogs as a treatment option for relapsed refractory patients (Greer et al., 2014). The 5- and 10-year survival rates of patients with hairy cell leukemia who are treated with nucleoside analogs exceed 90% and are now comparable with the general population (Dearden, Else, & Catovsky, 2011).

Lytic Bone Lesions in Hairy Cell Leukemia

Lytic bone lesions are considered a rare and unusual finding in cases of hairy cell leukemia, particularly at the time of presentation, but may be present in about 3% of all patients (Pemmaraju et al., 2015). The most prominent site of skeletal involvement tends to be the proximal femur neck or head, but other less common bony sites include the skull, ribs, humerus, vertebrae, tibia, and fibulae (Filippi, Franco, Marinone, Tarella, & Ricardi, 2007). In a systematic review of cases, the most common presenting symptom of bony involvement was localized pain, which is an uncommon symptom of hairy cell leukemia (Filippi et al., 2007). Investigations of patient-reported pain later identified lytic lesions on radiographic imaging. The predominant radiographic finding is osteolysis, or bone destruction with or without well-defined margins. Extensive osteoporosis and aseptic necrosis of the femur or humerus are rare but have been reported in the literature (Herold et al., 1988).

The underlying pathophysiology of bone lesions in hairy cell leukemia is unclear, but the postulated mechanism is the presence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in hairy cell leukemia, which is a growth mediator and that possibly leads to bone resorption (Gray et al., 2013). Treatment with purine analogs also seems to have a protective effect toward developing bone involvement (Filippi et al., 2007).

In two similar cases from the literature, Gray et al. (2013) reported the case of a woman with hairy cell leukemia with complaints of lower back and hip pain, normal blood work, and unremarkable x-rays, whereas a second case by Pemmaraju et al. (2015) reported a case of pathological fracture in a woman with breast cancer who experienced a fractured hip after trauma. A subsequent biopsy reported classical hairy cell leukemia. Painful lytic lesions with pancytopenia or splenomegaly can mimic metastatic carcinoma or other conditions, therefore delaying diagnosis and treatment (Gray et al., 2013). Lytic lesions respond well to local radiotherapy, and skeletal involvement rarely recurs and does not seem to influence overall prognosis (Filippi et al., 2007; Gray et al., 2013).

Implications for Nursing

Oncology nurses should be aware of the common and uncommon clinical presentations for the patient populations they care for. This knowledge may assist the clinical team to diagnosis disease complications early and minimize distress. Clinical assessments should be thorough and comprehensive, and should integrate routine screening for distress into practice. Screening for distress will ensure that new and escalating symptoms are addressed in a timely manner, and it has been recommended by Howell and Olsen (2011) that results be used as an initial red flag indicator of psychosocial healthcare needs. In the case study of Mrs. P, her initial reports of mild pain were attributed to a recent trauma. As her symptoms and distress progressed, a more in-depth assessment was warranted, which led to the unusual but known complication of bone involvement secondary to her hairy cell leukemia.

At first assessment, symptoms may not appear to be related to the patient’s underlying malignancy, but symptoms, which are causing patients to report significant distress, should be examined and necessary referrals made on the patients behalf. Individuals diagnosed with cancer are at risk of developing distress and psychological complications, such as anxiety or depression, throughout the cancer journey. Distress experienced in the form of depression or other adjustment difficulties is a significant problem for as many as 50% of all patients with cancer (Bultz & Carlson, 2005). Clinicians should reassess patients throughout the cancer journey to facilitate early assessment and intervention.

Conclusion

Patients who are experiencing emotional and psychological distress will lack motivation to follow through with interventions and referrals and require longer rehabilitation; therefore, oncology nurses must be vigilant and holistic in their assessments (Grassi et al., 2013). Such vigilance will ensure successful engagement in care and recovery (Andersen et al., 2014). Oncology nurses play a vital role in mitigating the negative emotional and behavior sequelae associated with distress. Screening and early intervention for those individuals who are manifesting symptoms of distress may minimize the negative impact and maladaptive coping.

References

Andersen, B.L., DeRubies, R.J., Berman, B.S., Gruman, J., Champion, V.L., Massie, M.J., . . . Rowland, J.H. (2014). Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(15), 1–15. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611

Bouroncle, B.A. (1994). Thirty-five years in the progress of hairy cell leukemia. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 14(Suppl., 1), 1–12.

Bultz, B.D., & Carlson, L.E. (2005). Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign in cancer care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 6440–6441. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3259

Damaj, G., Kuhnowski, F., Marolleau, J.P., Bauters, F., Leleu X., & Yakoub-Agha, I. (2009). Risk factors for severe infection in patients with hairy cell leukemia: A long-term study of 73 patients. European Journal of Hematology, 83, 246–250. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01259.x

Dearden, C.E., Else, M., & Catovsky, D. (2011). Long-term results for pentostatin and cladribine treatment of hairy cell leukemia. Leukemia and Lymphoma, 52(Suppl., 2), 21–24. doi:10.3109/10428194.2011.565093

Filippi, A., Franco, P., Marinone, C., Tarella, C., & Ricardi, U. (2007). Treatment options in skeletal localizations of hairy cell leukemia: A systematic review of the role of radiation therapy. American Journal of Hematology, 82, 1017–1021. doi:10.1002/ajh.20785

Forconi, F. (2011). Hairy cell leukemia: Biological and clinical overview from immunogenetic insights. Hematology Oncology, 29, 55–66. doi:10.1002/hon.975

Goodman, G.R., Burian, C., & Koziol, J.A. (2003). Extended follow up of patients with hairy cell leukemia after treatment with cladribine. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 891–896. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.05.093

Grassi, L, Johnasen, C., Annunziata, M.A., Capovilla, E., Costantini, A., Gritti, P., . . . Bellani, M. (2013). Screening for distress in cancer patients: A multicenter nationwide study in Italy. Cancer, 119, 1714–1721. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27902

Gray, M., Rutherford, M., Bonin, D., Patterson, B, & Lopez, P. (2013). Hairy cell leukemia as lytic bone lesions. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, e410–e412. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5301

Greer, J.P., Arber, D.A., Glader, B., List, A., Means, R.T., Paraskevas, F., & Rodgers, G. (Eds.). (2014). Wintrobe’s clinical hematology (13th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Grever, M. (2010). How I treat hairy cell leukemia. Blood, 115, 21–28. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-06-195370

Herold, C.J., Wittich G.R., Schwarzinger I., Haller, M.D., Chott, A., Mostbeck, G., & Hajek, M.D. (1988). Skeletal involvement in hairy cell leukemia. Skeletal Radiology, 17, 171–175. doi:10.1007/BF00351002

Hoffman, M. (2006). Clinical presentations and complications of hairy cell leukemia. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 20, 1065-1073. doi:10.1016/j.hoc .2006.06.003

Howell, D., & Olsen, K. (2011). Distress—The sixth vital sign. Current Oncology, 18, 208–210. doi:10.3747/co.v18i5.790

Janckila, A.J., Wallace, J.H., & Yam, L.T. (1982). Generalized monocyte deficiency in leukaemic reticuloendotheliosis. Scandanavian Journal of Hematology, 29, 153–160. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.1982.tb00577.x

Pemmaraju, N., Gill, J., & Krause, J. (2015). Hairy cell leukemia presenting with a lytic bone lesion. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 28, 65–66.

Venkatesan, S., Purohit, A., Aggarwal, M., Manivannan, P., Tyagi, S., & Mahapatra, M. (2014). Unusual presentation of hairy cell leukemia: A case series of four clinically suspected cases. Indian Journal of Blood Transfusion, 30(Suppl., 1), S413–S417. doi:10.1007/s12288-014-0442-9

About the Author(s)

Streu is a clinical nurse specialist at CancerCare Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. No financial relationships to disclose. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Forum or the Oncology Nursing Society. Streu can be reached at erin.streu@cancercare.mb.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org.