Coping With Moral Distress in Oncology Practice: Nurse and Physician Strategies

Purpose/Objectives: To explore variations in coping with moral distress among physicians and nurses in a university hospital oncology setting.

Research Approach: Qualitative interview study.

Setting: Internal medicine (gastroenterology and medical oncology), gastrointestinal surgery, and day clinic chemotherapy at Ghent University Hospital in Belgium.

Participants: 17 doctors and 18 nurses with varying experience levels, working in three different oncology hospital settings.

Methodologic Approach: Doctors and nurses were interviewed based on the critical incident technique. Analyses were performed using thematic analysis.

Findings: Moral distress lingered if it was accompanied by emotional distress. Four dominant ways of coping (thoroughness, autonomy, compromise, and intuition) emerged, which could be mapped on two perpendicular continuous axes: a tendency to internalize or externalize moral distress, and a tendency to focus on rational or experiential elements. Each of the ways of coping had strengths and weaknesses. Doctors reported a mainly rational coping style, whereas nurses tended to focus on feelings and experiences. However, people appeared to change their ways of handling moral distress depending on personal or work-related experiences and perceived team culture. Prejudices were expressed about other professions.

Conclusions: Moral distress is a challenging phenomenon in oncology. However, when managed well, it can lead to more introspection and team reflection, resulting in a better interpersonal understanding.

Interpretation: Team leaders should recognize their own and their team members’ preferred method of coping and tailored support should be offered to ease emotional distress.

Jump to a section

A range of definitions have emerged for moral distress (MD), leading to a concept that lacks conceptual precision (McCarthy & Deady, 2008). In 1984, Jameton stated, “Moral distress arises when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action” (p. 6). Raines (2000) adjusted this definition, stating that constraints can be more varied. Numerous studies have contributed by proposing internal and external barriers (e.g., fear of professional reprimands, lack of self-confidence, legal constraints, hospital policies) (Burston & Tuckett, 2013; Epstein & Hamric, 2009; Hamric, Davis, & Childress, 2006; Meltzer & Huckabay, 2004).

The psychological context of how MD takes shape (anger, frustration) usually is a key element when defining the concept (Repenshek, 2009). Kälvemark, Höglund, Hansson, Westerholm, and Arnetz (2004) connected MD to situations where the healthcare provider feels that he or she is not able to preserve all interests and values at stake. Caregivers may experience MD when their values are challenged (McCarthy & Deady, 2008). Indeed, MD is connected to day-to-day reality (Kälvermark et al., 2004), and it can lead to job dissatisfaction (De Veer, Francke, Struijs, & Willems, 2013), which can result in emotional exhaustion (Meltzer & Huckabay, 2004; Oh & Gastmans, 2015), burnout (Corley, 1995; Oh & Gastmans, 2015; Sundin-Huard & Fahy, 1999; Whitehead et al., 2015), staff turnover, and decreased quality of patient care (Burston & Tuckett, 2013; Corley, 2002).

Exploring ways of coping with MD can lead to a better understanding of ways in which caregivers try to reduce feelings of stress (Epstein & Hamric, 2009). To date, studies on MD have mainly focused on the critical care setting (De Villers & DeVon, 2013; McCarthy & Deady, 2008; Oh & Gastmans, 2015). However, non-critical care might offer more time to consider many treatment options, which strengthens the complexity of professional evaluation, therefore giving rise to MD (Rice, Rady, Hamric, Verheijde, & Pendergast, 2008). An oncology setting offers an excellent representation of these characteristics (Bohnenkamp, Pelton, Reed, & Rishel, 2015; Cohen & Erickson, 2006).

MD is commonly studied in nurses (Cohen & Erickson, 2006), presuming that they are unable to act on their beliefs and do not have the power to make final decisions (Kälvemark et al., 2004). However, the same goes for residents (Knifed, Goyal, & Bernstein, 2010; Lomis, Carpenter, & Miller, 2009) and senior staff (Abbasi et al., 2014; Chiu, Hilliard, Azzie, & Fecteau, 2008; Hilliard, Harrison, & Madden, 2007). Studies about MD in doctors, however, remain scarce (Berger, 2014; Kälvemark et al., 2004) despite an understanding of the importance of a multidisciplinary viewpoint (McCarthy & Deady, 2008), particularly since, in oncology, many professions work together. In addition, coping with MD can evolve during a career and might be influenced by the team context (Bruce, Miller, & Zimmerman, 2015; Hamric & Blackhall, 2007), organization culture (Knifed et al., 2010; Repensheck, 2009), training (Hilliard et al., 2007), or leadership (Goethals, Gastmans, & Dierckx de Casterlé, 2010).

This study starts from the following definition by the current article’s authors: MD is an experience of dissonance that may arise when a caregiver has a moral opinion about what is appropriate care in a given context, while, because of internal or external constraints, acting upon it is perceived as difficult or impossible. The study aims to (a) explore and compare how doctors and nurses with different levels of experience, working in three distinct oncology hospital wards, handle MD, and (b) gain insight into supportive and aggravating factors.

Methods

Using a qualitative research design and focusing on critical incidents, the authors’ goal was to gain more insight into the meaning-making strategies of professionals—and their way of dealing with MD—in a non-critical oncology setting with a distinct practice (surgery, internal medicine, and day clinic).

Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

Approval was given by the Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Interviewees were working in three types of hospital wards at Ghent University Hospital: internal medicine, gastroenterology, and medical oncology; gastrointestinal surgery; and day clinic chemotherapy.

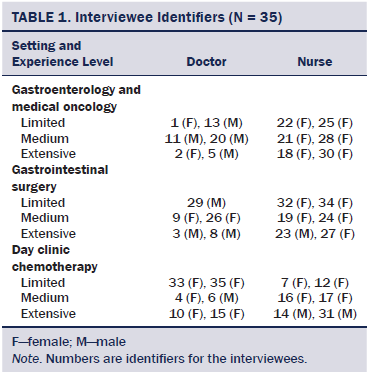

In 2013, the selected departments had 25%–100% of patients admitted with oncology diagnoses. Therefore, on a daily basis, professionals were confronted with complex ethical issues, inherent to a tertiary oncology setting. All caregivers were filtered in three experience levels (limited, medium, and extensive). Two nurses and two physicians were randomly selected per experience group (see Table 1) and per setting type. Each selected healthcare provider was contacted by email to explain the context of the interview study and ask for his or her voluntary participation. Participants were allowed to register this as work time. Interviews took place on campus (specific location was chosen by the interviewee) and were conducted individually with only one investigator present.

The Critical Incident Technique (CIT) (Flanagan, 1954) allowed the researcher to systematically gather retrospective experiences, in line with the chosen definition of MD, and elicit detailed narratives about three specific situations. Interviewees were invited to reflect on how their ways of experiencing and handling MD evolved during their career and how training and team climate affected their experiences. Doctors and nurses were also asked how they perceive MD to be experienced by other healthcare providers.

Analysis

All in-depth semistructured interviews were conducted by the first author. All interviews were typed out verbatim. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) allowed for an explorative, in-depth analysis of how nurses and doctors cope with MD, focusing on themes and patterns in the data.

The first author coded all interviews in detail using NVivo®, version 10, removed personal identifiers, and selected 10 interviews for extensive discussion with two supervisors of the project (second and seventh author), leading to identification of crucial themes and codes. These 10 interviews were a representation of both professions (five nurses and five physicians), of the different setting types, and of experience levels. They were selected because of their particularly informative character, being very rich in their narratives about critical incidents.

The first author then organized the complete data set by means of open coding. All interviews were reviewed in the light of the emerging model, by comparing frequencies, identifying theme co-occurrence, and graphically displaying relationships between different themes, leading to a model of four dominant ways of coping (see Figure 1). This model was systematically checked by all researchers against the raw data to provide, through triangulation (Malterud, 2001), good credibility and validity of the results.

Results

From March to October 2013, a sample of 17 medical doctors (9 female, 8 male) and 18 nurses (15 female, 3 male) were interviewed (mean = 57 minutes, range = 48–91 minutes) about how and when they experienced and handled MD. All interviewees recalled experiencing some emotional discomfort at the time the critical incident occurred (e.g., anger, frustration, regret, sadness). It could be argued, therefore, that MD always embodies emotional distress to a varying extent.

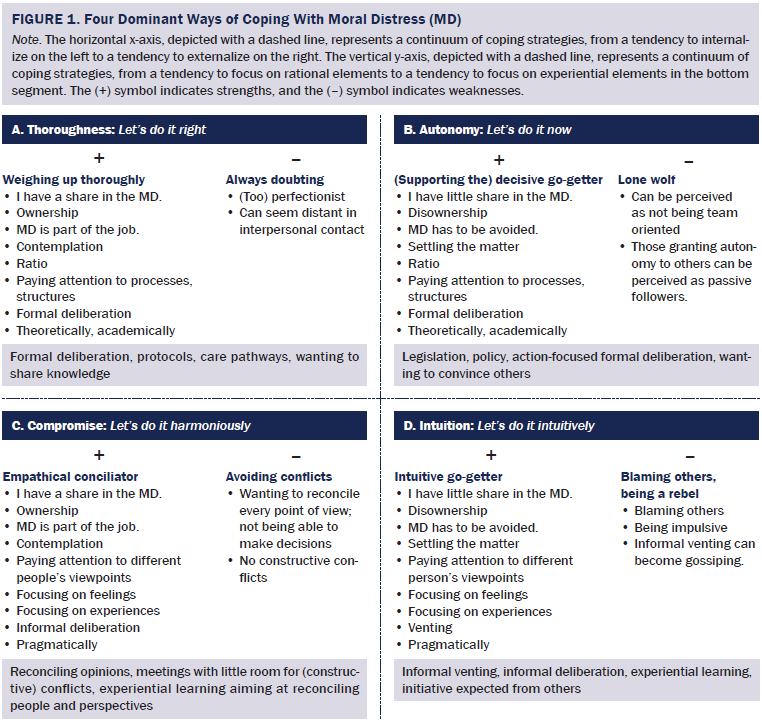

Although, within single interviews, a combination of different ways of coping could be observed, the authors discerned four dominant strategies for dealing with MD, which could be mapped on perpendicular continuous axes.

Internalizing or Externalizing Moral Distress

Characteristic of an internalizing way of coping is the feeling of being personally involved in a moral conflict. MD is considered as part of the job, which gives rise to a great deal of contemplation about idiosyncratic values and norms, leading to a feeling of ownership. They feel implicated in the experienced conflict.

An illustrative example could be found with a surgeon (8): “In fact, each case can cause a certain level of MD because I’m always reflecting on the choices I make and the steps I take.” Similarly, a nurse (23) said, “I really weigh up all possible outcomes. If things do not turn out for the better, I contemplate what I could have done differently.”

A dominantly externalizing way of coping, by contrast, is characterized by disownership, turning away from the question of one’s own values and norms, focusing on causes that are beyond one’s grasp. Healthcare professionals who use this way of coping most commonly prefer quick solutions.

An example could be found in the narratives of one of the nurses (24). “If you’re only working part-time, nobody can expect that you fully understand the moral complexity, or that you can start stepping into things.” A similar distancing attitude was observed in a resident (13). “Each three to four months, we switch to another department. It’s obvious, therefore, that it is not our call to be critical.” An internist (15) stated, “It’s not that I, as a person, should really doubt whether to start chemotherapy or not. There are evidence-based guidelines to start with, and, in the end, it’s the chemotherapy that does or doesn’t do its job.”

Focusing on Rational or Experiential Elements

Interviewees showing a preferential focus on rational elements when being confronted with MD mainly pay attention to theoretical and academic rationale, processes, and structures. They prefer well-structured formal deliberation to even out MD.

Illustrating this preference, a resident (4) explained, “Being a doctor, you have the huge advantage that you can step into a case dominantly using your knowledge, without really having to be empathic.” Suggestions for alleviating MD share the same characteristics, as illustrated by a surgeon (8). “What helps when experiencing MD is a well-structured formal debate with all parties included. You ideally have enough time for everybody to formulate their rationale and you have somebody who takes notes.” A nurse (27) similarly suggested, “What would help me are lectures about such subjects.”

Focusing on experiential elements implies a strong concern about the experiences and feelings of everyone involved, entailing a preference for experience-based learning and team discussions and for informal ways of handling MD.

A resident (26) illustrated her need for a more experiential team approach and support. “We do have debriefings sometimes, but they tend to focus on ‘how can we get things done better and more efficiently.’ It’s not that you can talk about how you feel and how a case affects you as a person.” One of the nurses (21) explained how she needs to feel other caregivers’ ability to express emotions, almost as a prerogative to discuss situations causing MD. “I once was involved in a situation where an oncologist had to tell a young woman that she would die within a short period of time. The woman started to cry, I cried, and the doctor cried. To me, that was beautiful. That’s the kind of doctor that I would feel comfortable talking to.”

When merging these axes into one model, the authors discerned four quadrants characterizing dominant ways of coping, each having its strengths (+) and weaknesses (-), and implying preferred solutions and learning styles: thoroughness, autonomy, intuition, and compromise.

Thoroughness: Caregivers preferring thoroughness as a way of coping with MD evaluate rational arguments and prefer formal deliberation, protocols, care pathways, and sharing knowledge. However, by internalizing MD and wanting to be thorough, they risk experiencing lingering doubt and being perfectionist and might be perceived as being distant.

Illustrative of this thoroughness, one of the surgeons (8) stated, “In my opinion, ethics are everywhere . . . in how you make an incision, how you stitch a wound, but also knowing the dos and don’ts of breaking bad news.” An internist (10) reflected on her perfectionism. “Well-structured care pathways and well-coordinated team meeting can ease MD. I know I expect a lot from my team, but I’m also very self-critical.”

Autonomy: Doctors and nurses preferring this way of coping with MD highly value autonomy. They like to settle things quickly when placed in a hierarchical position. Nurses and junior residents, being in a subordinate role, choose to grant autonomy to superiors when being involved in MD situations. The pitfall of this style is that a person might be identified as not being team oriented or as being a passive follower.

One of the internists (15) presented scientific knowledge as a barrier against MD, preferring quick external solutions. “If certain laws, protocols, and hospital policies do not change, MD will only become a bigger issue.” A surgeon (3) firmly believed in autonomy as a barrier against MD. “The older you are, the more you climb the hierarchical ladder, the more you can freely call the shots. Therefore, senior staff are not really affected by MD.” One of the residents (13) explained how, for him, the autonomy of his supervisor was sacred when experiencing MD. “I will never go into a discussion about moral themes with my supervisor. I will do as I am told.”

Compromise: Characteristics for participants situated in this quadrant include opting for a compromising coping style; they want to reconcile opinions pragmatically and informally. Such an attitude secures smooth cooperation, but can be a pitfall because of avoiding conflicts.

One of the physicians (2) illustrated such desire for harmony by referring to personal goals. “It is my job to provide good palliative care, trying to make patients and their relatives feel good about the whole process. To act in such a way that when patients unfortunately die, relatives cherish positive memories, even in, let’s say, 10 years’ time.” A colleague (5) expounded on the difficult search for consensus. “For me, it is important, when experiencing MD, to find a compromise between my personal opinion and my team’s opinion. That can be a complex exercise. I am aware of the fact that I tend to avoid conflicts.”

Intuition: Some caregivers tend to be intuitive go-getters when handling MD. They focus on feelings and experiences, choosing pragmatic solutions. They usually externalize MD and can point the finger when moral issues arise, sometimes acting quite impulsively. Their informal venting might lead to gossiping.

A nurse (22) illustrated this as follows: “I usually follow my gut feeling. When I get a hunch that, in my opinion, things are not right, I will just say what’s on my mind, sometimes a bit too impulsively.” A colleague (27) explained how intuition plays a dominant role in evaluating appropriateness of care. “I always wonder, ‘What would I want the doctor to do if it where my mother or father?’ To me, that’s a good benchmark.”

Profession and Setting Type

Three interviewees (2 internists, 1 surgeon) could be characterized by a dominant style A; 11 style B (2 day clinic nurses, 2 surgeons, 7 internists); 8 style C (3 nurses and 5 physicians from different setting types); and 13 style D (all nurses, no physicians, from different setting types). In the current study, physicians more often preferred a rational coping style, whereas nurses focused more on feelings and experiences. No distinctive differences could be found in comparing a surgical, internal medicine, or day clinic setting.

Remarkably, many prejudices were expressed about other disciplines. An internist (10) stated, “Surgeons are not really interested in moral considerations. They can hide behind the technical complexity of their discipline.” A surgeon (3) explained, “Internists do not really experience MD, in my opinion. They rarely have to make split-second decisions; time is on their side.” One of the nurses (34) argued that, “Doctors do not experience MD because they only walk into a patient’s room for 10 minutes, and that’s too short a moment to generate MD.” A resident (35) explained that, “Strangely enough, I have never heard a supervisor talk about MD.” She was convinced that this was a missed teaching opportunity.

Years of Experience

Participants could not be differentiated in terms of years of experience. A remarkable number of caregivers believed that MD would gradually decrease or even disappear thanks to experience and by having more authority or autonomy (1, 4, 9, 12, 22, 25, 29). Others believed that ethical reflection is not a priority during the first years on the job, when acquiring knowledge and skills (7, 9–13, 16, 19, 20, 21, 27, 28, 32). However, ways of coping seem to change throughout people’s careers, and were influenced by personal or work-related experiences: “Through personal experiences, thinking about ethical topics has become self-evident” (17), or “Since a relative died of cancer, I really understand that being a doctor is not only about knowledge and technical skills; it’s about trying to understand what he or she goes through. This is the touchstone of appropriate care” (8). Experiences might also alter coping preferences. “[A young patient] was dying and asked me to hold her. I couldn’t. I just froze. From then onwards, I never let a story come that close again. So, when I experience MD, I just act upon doctor’s orders, and I hope the rest of the team keeps that same distance” (14).

Work Climate

Perceived team climate and leadership seemed to play an important role. One of the nurses (12) explained, “We can call doctors by their first name. Sounds great, but I think it is contradictory. Sometimes, they barge in without saying ‘hi’, asking you something, and they’re off again. When I experience MD, that is not really inviting to speak up, is it?” Another nurse (31) perceived the team culture as rather indifferent toward moral concerns, in analogy to his personal point of view. “MD is not a big concern of us. We have so many things to do and so little time that we just have to act upon the given instructions. No time to start philosophizing.” In some cases, a penalization culture was perceived, acting as a barrier against discussing moral concerns. “I learned to keep my mouth shut. I will never question my supervisor’s decisions, even when I completely disagree. I have my career to protect” (29). Similarly, another nurse (30) noted, “Whenever we are critical, this doctor responds that it is clear that we desperately need a holiday. Then you learn to just hold your thoughts.”

From Threat to Opportunity

MD also can enhance introspection, both at individual or at a team level, leading to insight and growth. “It is important to have different viewpoints. OK, it can be hard. There can be discussion or even hard feelings, but in the end, you can grow closer as a team” (2). “Even in complex discussion, I feel supported, and I learn from others because we are all reflecting about what is best for the patient, and that is a binding factor” (7).

Discussion

In this study, doctors particularly reported rational ways of coping with MD, whereas nurses tended to focus on feelings and experiences, resulting in different support preferences. This suggests that interprofessional imbalances might arise when having to address morally complex situations, when leaving no space for acknowledging and understanding differences. Nurses and junior doctors did not always feel confident enough to put forward moral beliefs. The argument could be made that they, therefore, chose a rational way of coping, granting autonomy to their superiors, while they actually may prefer a different coping style later in their career or in a different setting. This is in line with findings from Sundin-Huard and Fahy (1999), who reported that nurses often do nothing, use covert communication, or sense that direct confrontation is counterproductive when experiencing MD, and with findings of Chiu et al. (2008) and Knifed et al. (2010), who suggested that doctors who are in training are fearful of reprisals.

Most people seem unaware of their own and team members’ preferred coping style. In addition, they expressed prejudices about other professions. These prejudices can create serious obstacles on the path of meaningful communications between physicians and nurses, as well as between caregivers of the different setting type.

The current study focused on individual coping styles, but distress seems very much linked to a broader organizational context (De Veer et al., 2013; Førde & Aasland, 2008; Goethals et al., 2010). Additional research could, therefore, focus more specifically on leadership, team culture, team dynamics, and interactions, with special attention to the complex process of ethical decision making.

Implications for Practice

Professionals should focus on handling feelings of powerlessness in constructive ways, not by trying to erase MD, but by acknowledging it and perhaps by being offered tailored support on the job (McCarthy & Deady, 2008). Although specialized theoretical knowledge, protocols, and advanced skills training are essential (Abbasi et al., 2014), these are insufficient for helping individual caregivers to cope with these complex ethical challenges (Devisch & Vanheule, 2014; Goethals et al., 2010). Programs should focus on pragmatic, lifelong, on-the-job training for dealing with MD (Berger, 2013), taking into account people’s spontaneous ways of coping with MD (e.g., tailor-made training sessions focusing on theoretical topics and experiential learning). Lack of resources (e.g., lack of financial means, lack of time) will make this a challenge (Kälvemark et al., 2004).

Team leaders should be aware of the impact perceived team culture has and should recognize their own and their team members’ preferred ways of coping, acknowledge the richness of diversity, which might result in a better mutual understanding, and provide tools for more constructive team meetings, in a non-punitive environment (Chiu et al., 2008; Rager Zuzelo, 2007).

As illustrated by some interviewees, MD can make up a challenge and opportunity, which might lead to increased introspection, team reflection, creative solutions, and opportunities for personal transformation and growth (Hanna, 2004). Indeed, as is stated in the interviews, with sufficient support, MD can also result in satisfactory feelings of accomplishment of professional goals (Lützén, Cronqvist, Magnusson, & Andersson, 2003). It can make individuals more aware of and reflective about their own moral beliefs, strengthening their motivation to do better next time (Knifed et al., 2010; McCarthy & Deady, 2008; Rager Zuzelo, 2007).

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Although this qualitative study reveals new areas for investigation and strengthens the conceptual understanding of MD, findings cannot be generalized to other settings or caregivers. Data reflect the view of a small number of nurses and physicians in a university oncology setting.

In addition, this study did not control for many variables that may be related to MD coping strategies, such as degree, ethics education, and experiences. Those with advanced education may be more acquainted with biomedical ethics and ethical reasoning, possibly leading to more assertiveness (Rager Zuzelo, 2007) and, therefore, a different coping style.

Conclusion

MD is part of everyday reality in multidisciplinary cancer care. Ways of coping with MD could be situated on two axes: on the one hand, having a tendency to internalize or externalize MD; on the other hand, a tendency to focus on rational or experiential MD elements. Based on these axes, the authors formulated four dominant ways of coping, each incorporating strengths and weaknesses. However, ways of coping were not static and changed according to private or work-related experiences and perceived organization or team culture. MD creates a challenging phenomenon in oncology. However, when managed well, it can engender more introspection and team reflection, resulting in a better interpersonal understanding.

References

Abbasi, M., Nejadsarvari, N., Kiaki, M., Borhani, F., Bazmi, S., Nazari Tavaokkoki, S., & Rasouli, H. (2014). Moral distress in physicians practicing in hospitals affiliated to medical sciences universities. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16, e18797.

Berger, J. (2013). Moral distress in medical education and training. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, 395–398.

Berger, J.T. (2014). Moral distress in medical education and training. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, 395–398. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2665-0

Bohnenkamp, S., Pelton, N., Reed, P.G., & Rishel, C.J. (2015). An inpatient surgical oncology unit’s experience with moral distress: Part I. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42, 308–310. doi:10.1188/15.ONF .308-310

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/ 1478088706qp063oa

Bruce, C.R., Miller, S.M., & Zimmerman, J.L. (2015). A qualitative study exploring moral distress in the ICU team: The importance of unit functionality and intrateam dynamics. Critical Care Medicine, 43, 823–831. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000822

Burston, A., & Tuckett, A. (2013). Moral distress in nursing: Contributing factors, outcomes and interventions. Nursing Ethics, 20, 312–324. doi:10.1177/0969733012462049

Chiu, P.P., Hiliard, R.I., Azzie, G., & Fecteau, A. (2008). Experience of moral distress among paediatric surgery trainees. Journal of Paediatric Surgery, 43, 986–993. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.016

Cohen, J.S., & Erickson, J.M. (2006). Ethical dilemmas and moral distress in oncology nursing practice. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 10, 775–780. doi:10.1188/06.CJON.775-780

Corley, M.C. (1995). Moral distress of critical care nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 4, 280–285.

Corley, M.C. (2002). Nurse moral distress: A proposed theory and research agenda. Nursing Ethics, 9, 636–650. doi:10.1191/09 69733002ne557oa

De Veer, A.J., Francke, A.L., Struijs, A., & Willems, D.L. (2013). Determinants of moral distress in daily nursing practice: A cross sectional correlational questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.017

De Villers, M.J., & DeVon, H.A. (2013). Moral distress and avoidance behavior in nurses working in critical care and noncritical care units. Nursing Ethics, 20, 589–603. doi:10.1177/0969733012452882

Devisch, I., & Vanheule, S. (2014). Singularity and medicine: Is there a place for heteronomy in medical ethics? Journal of Evaluation of Clinical Practice, 20, 965–969. doi:10.1111/jep.12110

Epstein, E.G., & Hamric, A.B. (2009). Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. Journal of Clinical Ethics, 20, 330–342.

Flanagan, J.C. (1954). The Critical Incident Technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51, 327–358. doi:10.1037/h0061470

Førde, R., & Aasland, O. (2008). Moral distress among Norwegian doctors. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34, 521–525. doi:10.1136/jme.2007.021246

Goethals, S., Gastmans, C., & Dierckx de Casterlé, B. (2010). Nurses’ ethical reasoning and behaviour: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 635–650. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu .2009.12.010

Hamric, A., & Blackhall, L. (2007). Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of the dying patients in intensive care units: Collaboration, moral distress and ethical climate. Critical Care Medicine, 35, 422–429. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D

Hamric, A.B., Davis, W.S., & Childress, M.D. (2006). Moral distress in health care professionals. Pharos, 69, 16–23.

Hanna, D.R. (2004). Moral distress: The state of the science. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 18, 73–93. doi:10.1891/rtnp.18.1.73.28054

Hilliard, R.I., Harrison, C., & Madden, S. (2007). Ethical conflicts and moral distress experienced by paediatric residents during their training. Paediatrics and Child Health, 12, 29–35.

Jameton, A. (1984). Nursing practice: The ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kälvemark, S., Höglund, A., Hansson, M., Westerholm, P., & Arnetz, B. (2004). Living with conflicts—Ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1075–1084. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00279-X

Knifed, E., Goyal, A., & Bernstein, M. (2010). Moral angst for surgical residents: A qualitative study. American Journal of Surgery, 199, 571–576. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.04.007

Lomis, K., Carpenter, R., & Miller, B. (2009). Moral distress in the third year of medical school: A descriptive review of student case reflections. American Journal of Surgery, 197, 107–112. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.07.048

Lützén, K., Cronqvist, A., Magnusson, A., & Andersson, L. (2003). Moral distress: Synthesis of a concept. Nursing Ethics, 10, 312–322. doi:10.1191/0969733003ne608oa

Malterud, K. (2001). The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet, 358, 397–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9

McCarthy, J., & Deady, R. (2008). Moral distress reconsidered. Nursing Ethics, 15, 254–262. doi:10.1177/0969733007086023

Meltzer, L.S., & Huckabay, L.M. (2004). Critical care nurses’ perceptions of futile care and its effect on burnout. American Journal of Critical Care, 13, 202–208.

Oh, Y., & Gastmans, C. (2015). Moral distress experienced by nurses: A quantitative literature review. Nursing Ethics, 22, 15–31.

Rager Zuzelo, P. (2007). Exploring the moral distress of registered nurses. Nursing Ethics, 14, 344–359. doi:10.1177/0969733007075870

Raines, M.L. (2000). Ethical decision making in nurses. Relationships among moral reasoning, coping style, and ethics stress. JONA’s Healthcare Law, Ethics and Regulation, 2, 29–41. doi:10.1097/00128488-200002010-00006

Repenshek, M. (2009). Moral distress: Inability to act or discomfort with moral subjectivity? Nursing Ethics, 16, 734–742. doi:10.1177/0969733009342138

Rice, E., Rady, M., Hamric, A., Verheijde, J., & Pendergast, D. (2008). Determinants of moral distress in medical and surgical nurses at an adult acute tertiary care hospital. Journal of Nursing Management, 16, 360–373. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00798.x

Sundin-Huard, D., & Fahy, K. (1999). Moral distress, advocacy and burnout: Theorizing the relationships. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 5, 8–13. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172x.1999.00143.x

Whitehead, P., Herbertson, R., Hamric, A., Epstein, E., & Fisher, J. (2015). Moral distress among healthcare professionals: Report of an institution-wide survey. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47, 117–125. doi:10.1111/jnu.12115

About the Author(s)

Lievrouw is a psychologist in the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the Ghent University Hospital in Belgium; and Vanheule is a professor in the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Deveugele is a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, De Vos is a professor in the Department of Gastroenterology, Pattyn is a professor and head of the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Van Belle is a medical professor in the Department of Medical Oncology, and Benoit is head of the Department of Intensive Care, all at Ghent University. This research was funded by the Oncology Scientific Work Group at Ghent University Hospital in Belgium. Benoit is a part-time senior clinical investigator for the Research Foundation Flanders. Lievrouw completed the data collection. Lievrouw, Benoit, and Vanheule provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the conceptualization, design, and manuscript preparation. Lievrouw can be reached at an.lievrouw@uzgent.be, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted July 2015. Accepted for publication September 27, 2015.