Video-Based Patient Rounds for Caregivers of Patients With Cancer

Purpose: To investigate caregivers’ experiences and level of involvement with video-based patient rounds.

Participants & Setting: 17 caregivers of patients with cancer at Odense University Hospitals in Denmark.

Methodologic Approach: Field observation and semistructured interviews were employed. Interpretative phenomenologic analysis was used for data analysis. 17 interviews with caregivers and 190 hours of observations were conducted.

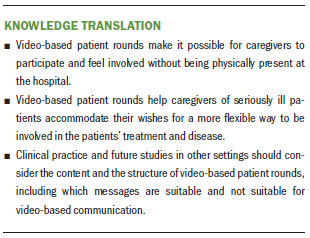

Findings: Video-based patient rounds made it possible for caregivers to attend without being physically present at the hospital. This allowed flexibility in caregivers’ daily lives. However, caregivers also noted limitations in the use of video, particularly when conversations with healthcare professionals included serious messages. In that context, physical presence was preferred.

Implications for Nursing: This study highlights the importance caregivers place on involvement and how video-based patient rounds allow caregivers to participate without being physically present at the hospital. The structure of video-based patient rounds and the topic of conversation should be considered.

Jump to a section

Patients with cancer may find themselves in vulnerable situations because of demanding treatments and serious side effects (Dieperink, Coyne, Creedy, & Østergaard, 2018; Nilsen & Johnson, 2017). Therefore, involvement of caregivers can be beneficial during hospitalization (Nilsen & Johnson, 2017). A cancer diagnosis affects the whole family, and it can cause physical, mental, and emotional strain for caregivers (Benzein, Johansson, Årestedt, & Saveman, 2008; Nilsen & Johnson, 2017; Northouse, Williams, Given, & McCorkle, 2012). Studies confirm the demand on caregivers, who are often seen as the most important resource in helping patients cope with illness and disease (Benzein et al., 2008; Northouse et al., 2012). Caregivers need information and support, and this need is not always covered (Dieperink et al., 2018; Eriksson & Lauri, 2000; Heynsbergh, Heckel, Botti, & Livingston, 2018; Kim, Kashy, Spillers, & Evans, 2010). A trusting relationship between nurses and caregivers can reduce caregivers’ feelings of stress and give caregivers the sense that they are being seen, heard, and respected (Blindheim, Thorsnes, Brataas, & Dahl, 2013; Heynsbergh et al., 2018; Northouse et al., 2012). Communication between healthcare professionals and caregivers is crucial for establishing a trustworthy and caring relationship (Leahey & Wright, 2016; Wright & Leahey, 2013). However, long distances to the hospital and work and family obligations can limit caregivers’ communication with healthcare professionals. This is particularly challenging during patient rounds, which are often completed in the morning and on weekdays when the caregiver may be at work (Stelson et al., 2016; Yager, Clark, Cummings, & Noviski, 2017). Given that it is important to include caregivers in patient rounds, new and innovative ways to communicate, such as telehealth, may be considered. Therefore, the authors of this article investigated whether a video-based patient rounds format would reduce these challenges.

In palliative care, research has shown that video consultations may be a way to accommodate the family perspective and include caregivers who care for patients at home (Funderskov et al., 2018; Parker Oliver et al., 2010; Wittenberg-Lyles, Goldsmith, Ferrell, Ragan, & Apker, 2014). Caregivers reported that the technology provided them with a feeling of flexibility and freedom (Funderskov et al., 2018; Parker Oliver et al., 2010). However, a literature search revealed that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies have been published that investigate the perspective of caregivers who were able to view a video link to patient rounds for hospitalized patients with cancer. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate caregivers’ experiences and involvement with video-based patient rounds.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Data collection took place in the Department of Haematology from November 2017 to January 2018 and in the Department of Oncology from October 2018 to December 2018 at Odense University Hospital in Denmark. Participants were caregivers of hospitalized patients with cancer. Eligible patients were identified by nurses and physicians. All included patients were able to speak Danish and expected to be hospitalized for more than two days. The patient defined which caregiver or caregivers to invite. It could be a family member, a friend, or other person of importance to the patient. Descriptive statistics (age, gender, education level, and relation to the patient) were collected from all caregivers. To be included, the caregivers had to have a smartphone, tablet, or personal computer with Internet access.

Methodologic Approach

The study used a qualitative, exploratative approach inspired by a phenomenologic and hermeneutic perspective. The underlying conceptual framework of this study was drawn from a family perspective (Leahey & Wright, 2016; Wright & Leahey, 2013). The family is considered the unit of assessment and investigation; members interact and influence one another, particularly in response to health adversity. This perspective enables researchers to explore the patient and caregivers as a group, rather than focusing on the patient alone (Leahey & Wright, 2016; Wright & Leahey, 2013).

The methods included field observations made during the video-based patient rounds and semistructured interviews with caregivers. Interpretative Phenomenologic Analysis (IPA) was used for data analysis (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009) to obtain insight into the perspective of the caregivers.

The Cisco Jabber application was used for the video link to patient rounds. The caregivers who agreed to participate were sent a guest link to Cisco Jabber by email, which connected them to a secure virtual meeting room. Each link was encrypted and individualized. More than one caregiver per patient was able to participate at a time, even if they were not in the same geographic location. This was done by using the same link. Nurses and physicians used the Cisco Jabber client function on a tablet to connect to the caregiver or caregivers at the appointed time.

Field observation: Field observation in the two departments were conducted three days a week during a period of 12 weeks. Field observation was chosen because it allowed the researchers to obtain knowledge about dialogue and interactions taking place among the participants without interference from the researchers (Green & Thorogood, 2014). As such, the field observations were carried out using two methods inspired by Green and Thorogood’s (2014) description of varying positions the researcher can take in the field—an active role as participant as observer or an observing role as complete observer. As researchers in both departments, the first and second authors entered the social settings in the role of participant as observer when patients and caregivers were recruited. The authors were in dialogue with caregivers and responsible for setting up the technology behind the video link to patient rounds. During the actual session, the authors moved to the background and entered the role as complete observer. Field notes were taken and transcribed into a continuous text to ensure correct recall.

Semistructured interviews: Semistructured interviews allowed the authors to engage in a dialogue where their initial questions were modified in light of the caregivers’ responses. This enabled the authors to probe interesting and important topics that arose (Smith et al., 2009). The first and second authors conducted private interviews in person, via video, or via telephone, depending on each caregiver’s preference. An interview guide was developed with the following topics: introduction of the caregiver, experience with technology, experience with video-based patient rounds, relationship to the patient and roles during the patient rounds, and involvement in the patient’s disease and treatment. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Interpretative Phenomenologic Analysis

The study employed IPA because of its dual emphasis on describing and interpreting the personal meaning of particular experience of major significance (Smith et al., 2009). IPA is phenomenologic because it explores experiences and adds ideographic and hermeneutic philosophy to interpret a small sample size.

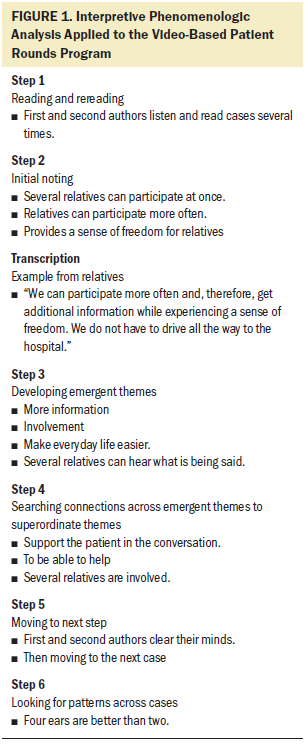

Each interview was listened to and the transcription was read multiple times to gain a holistic sense of the caregiver’s description, followed by initial noting with descriptive comments (Smith et al., 2009). The first and second authors read the transcripts separately, followed by discussions to identify themes and codes in the data. The steps involved finding emergent themes and then patterns across the emergent themes, ending with superordinate themes (see Figure 1). Themes were arranged using Nvivo, version 11.0, to ensure identification of divergence and convergence in the data. The data analysis was verified by the senior researcher.

Ethical Considerations

In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2008), the caregivers received oral and written information about the study and were included after providing informed consent. Participants were informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency (17/43851), and data were stored securely on a SharePoint site.

Findings

Participants

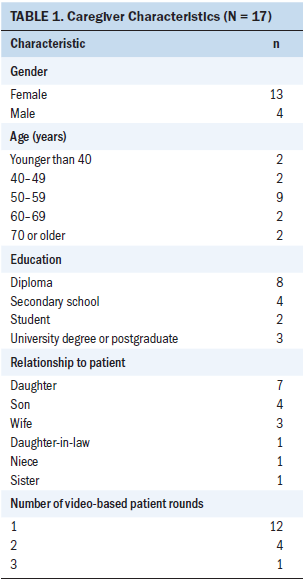

Seventeen caregivers (4 men and 13 women), aged 30–76 years, with a mean age of 54 years, were included in the study (see Table 1). A total of 190 hours of field observation and 17 interviews were conducted: two in-person interviews, three via video, and 10 via telephone. The interviews ranged from 30 to 45 minutes.

Themes

Three themes emerged through the analysis: four ears are better than two, freedom and flexibility, and to give a hug if needed (see Figure 2).

Four ears are better than two: Caregivers said that they would like to be involved in the patient’s treatment or disease trajectory. Video-based patient rounds gave them the opportunity to listen to the physicians and nurses, and caregivers could also contribute to the conversation via a microphone on their device. In this way, the caregivers could ask or clarify questions or help the patient to remember what was said. They appreciated being able to hear and convey the information given. In some context, caregivers recognized that the patient was unable to understand and remember what was said, and the caregivers felt that they could be helpful in such situations.

My mother-in-law forgets easily, and the days are all alike when you are hospitalized. It is of great importance that I can participate . . . then two of us can listen.

Caregivers explained that it was not only beneficial for the patient, but also for the healthcare professionals. Their participation in video-based patient rounds enabled them to contribute to the caregivers’ perspectives. The caregivers gained a better insight into the patient’s hospitalization and contributed important information to the healthcare professionals. Caregivers experienced that their participation could add to the conversation. The caregivers could support the patient’s wishes for the future and provide the healthcare professionals with knowledge about the patient. According to one caregiver, “I was my mother’s advocate. . . . I permitted myself to say what I thought was the best for my mother.”

It was possible for several caregivers to participate simultaneously on the screen. The following field note from a test session details how the process worked:

The patient’s two sons participate at the same time on the screen. One son was at work and the other was in the car. The sons talk with their mother [the patient] and agree what to discuss for the patient round. They are waiting for the doctor.

The caregivers reported a good experience and felt that the video-based patient rounds met the family perspective and their need for involvement in the patient’s treatment. One caregiver said the following:

It’s nice that both my brother and I could participate on the screen. Then I do not have to call the whole family afterward and recount what has been said about my mother’s treatment.

Freedom and flexibility: The majority of the interviewed caregivers were employed, which posed challenges in relation to participating in traditional patient rounds that are often arranged in the morning hours. Caregivers described that work responsibilities often hindered them from being as involved as they wanted and stated that video-based patient rounds could meet some of the challenges. One caregiver said the following:

It’s difficult to get off work all the time and drive the long way to be a part of the patient rounds. When I attend by video screen, it only takes 10 minutes and I can go back to work.

Long geographic distances meant that the caregivers, in many cases, were unable to be involved to the extent they wanted to. Video-based patient rounds helped accommodate their wishes for a more flexible way to be involved in the patient’s treatment. They reported that participation in video-based patient rounds granted time for other activities. One caregiver described how she had participated in video-based patient rounds from abroad, and another time she participated from a rest area on her way to a meeting. The following is an excerpt from a field note on the subject:

The patient’s daughter calls at the arranged time. She is in her car. The image on the screen is clear. The daughter and the patient smile to each other. The nurse stands by the bed. The patient, daughter, and nurse talk about how it is going.

The caregivers reported that they received important information and felt more involved in the course of disease and treatment than during previous hospitalizations.

The son said that the opportunity to participate in the video consultation was like [something] sent from heaven; he [received] important information and asked if it could be repeated later that week.

To give a hug if needed: Caregivers experienced some limitations in video-based patient rounds. Caregivers had thoughts about what messages they did not want shared through a screen, such as when a serious message was given. They wanted to be able to have physical contact with the patient and give a hug, if needed. However, they also expressed that, if the alternative was that the patient was alone when the serious message was given, video could at least be used as a substitute for physical presence.

I want to be there, physically, if it’s a serious message . . . to give a hug. I would not say that you can’t use it for serious messages, because the alternative would be that I would not be there at all.

Several caregivers had previously reported that patients shut down mentally and were not able to remember any of the conversation after the doctor had given a serious message. Caregivers suggested that the content of the conversation be defined in advance so no unexpected negative messages were received. The following excerpt is taken from field notes:

The conversation takes an unexpected turn. Patient and daughter are silent while the doctor speaks. The nurse says nothing. Daughter and patient talk a little together. The daughter is sad. They agree that they will see each other tomorrow.

In addition, after the video-based patient rounds, some caregivers had a feeling that the patient may have felt alone after the screen was turned off. They were worried that the patient was frustrated or sad, and it may be difficult if there was no one to share the experience with. After the video-based patient rounds, one daughter said the following about the situation:

I would like to have been with my mother . . . to discuss it with her face-to-face instead of sitting at home behind a tablet.

A few caregivers stated that they felt inadequate and overlooked during the video-based patient rounds. “I felt that the doctor forgot me . . . sitting behind the screen at home.”

Discussion

The authors aimed to investigate how caregivers experienced video-based patient rounds and, particularly, their involvement in the patient’s disease and treatment. The overall finding was that video-based patient rounds made it possible for caregivers to attend the patient rounds in a more flexible way. It facilitated their presence without them being physically present at the hospital and gave them a feeling of involvement, along with a sense of freedom in their everyday lives. However, limitations were found, particularly when the messages that were addressed were serious.

This study showed that video-based patient rounds gave caregivers the possibility to attend more often during patient rounds because it was not necessary to take job obligations or geographic distances into account. As such, the use of video-based patient rounds enabled the inclusion of their perspectives and led to stronger involvement in the conversation. Nurses report that the lack of a caregiver presence is a significant barrier, particularly when a healthcare system must involve family members (Coyne & Dieperink, 2017). Stelson et al. (2016) found that caregivers of patients admitted in an intensive care unit experienced logistical challenges, which affected their ability to participate in daily patient rounds. These challenges are, for example, living far from the hospital, performing duties at work, and having conflicts with the scheduled time of the patient rounds (Stelson et al., 2016). In a study by Epstein, Sherman, Blackman, and Sinkin (2015) conducted at a children’s hospital, similar logistical challenges were accommodated by inviting caregivers to participate by video if they were unable to be present at the hospital. Epstein et al. (2015) found that this video connection allowed caregivers to receive, directly from the physician, information concerning the patient’s disease and treatment they otherwise would not have received. This was consistent with the findings of the current study.

Family-centered care is an important approach for patients (Epstein et al., 2015; Yager et al., 2017). The current authors’ findings confirm that caregivers see their involvement as being one of support for the patient; the phrase “four ears are better than two” refers to their possibility of helping the patient remember and understand the information. Using technology as part of family-centered care is found in a systematic review by Kynoch, Chang, Coyer, and McArdle (2016), who aimed to make recommendations for clinical practice to address family needs of patients admitted to a critical care unit. They concluded that future intervention studies must focus on family needs by including technology and interventions specifically designed to improve the family members’ flexibility (Kynoch et al., 2016). The results of the current study indicate that technology was able to create more flexibility, leading to a new way of facilitating a family perspective by making it easier to attend patient rounds. Video-based patient rounds created the opportunity for more caregivers to participate simultaneously.

The data also showed that the relationship between healthcare professionals and caregivers was not always without challenges when using technology. Although caregivers appreciated the visual presence, it could be difficult to communicate via video screen. It created a feeling of distance, and some caregivers felt overlooked in the conversation. The importance of empathy and communication skills of the attending nurse and physician was also identified by Stelson et al. (2016) and Yager et al. (2017). They found that open, appreciative, and structured communication is vital if a family perspective was to be accommodated. However, this was not always the case in the current study; some caregivers perceived themselves as spectators to the conversation. This had a negative influence on the relationship between the healthcare professionals and the caregiver, and several caregivers asked for clarity on the content prior to the video-based patient rounds to prevent serious messages being given unexpectedly. Therefore, it is relevant to look into those aspects of video-based patient rounds.

The use of technology in patient rounds is new, and healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers had to learn how to communicate through the video screen. Collier et al. (2016) reported the same challenges, finding that communication and the use of technology might be influenced by the user’s comfort with that technology. In that context, training and supervision are important.

In the current study, caregivers experienced a need for a clear structure and clarification of the content in the conversation because they felt that this structure could prevent them from feeling overlooked and being emotionally affected afterward. To meet the communication challenges and comply with the caregivers’ wishes for a clear structure or framework of the conversation in video-based patient rounds, future clinicians may find the 15-minute family interview framework useful (Wright & Leahey, 1999). The framework is a guide for healthcare professionals to create a clear structure during brief family interviews. However, this framework does not include technology. Although the interview is short (15 minutes), Wright and Leahey (1999) note that the guide also takes the family members’ wishes for involvement into account and clarifies the resources for the family.

Strength and Limitations

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. In addition, the necessity of having Internet access could have hindered some from using the service. The majority of caregivers in the study were employed, and there was an overrepresentation of women. This pattern is in line with existing research showing that women are often the primary caregivers (Aguiló, García, Arza, Garzón-Rey, & Aguiló, 2018; Bruun, Pedersen, Osther, & Wagner, 2011).

IPA is a research design that allows investigation of the individual’s experience with a high degree of detail and depth, leading to unique experiences of the participants (Smith et al., 2009). However, IPA is most suitable for informants who are good at accounting for their experiences (Tuffour, 2017). Mixing the two methods—semistructured interviews and field observations—is considered a strength of this study because it permits statements from the relatives to be supported and validated by observations, leading to a broader understanding of the investigated phenomenon.

Implications for Nursing

Video-based patient rounds were tested and evaluated by the users, and important knowledge for nursing was revealed in terms of ways to involve family members’ and caregivers’ wishes. Healthcare professionals are able to systematically apply the family perspective and use caregivers’ insights to gain knowledge about the patient and family members, allowing care to be personalized. Video-based communication presents multiple opportunities within the nursing practice, including use in noncancer settings and as a means of symptom assessment. Additional studies are needed with larger sample sizes and multiple sites of care. An interesting aspect of future research may be to study the impact of video-based patient rounds on caregivers’ reduced travel time and leave from work.

Conclusion

Video-based patient rounds were able to accommodate the family perspective and create more flexibility in the way that caregivers were involved. Caregivers felt involved in the patient’s disease and treatment, and they could contribute information and receive important messages. Caregivers appreciated the virtual contact, but communication by screen could create a feeling of distance, particularly in situations where a serious message is given. Considerations about the form of communication and the structure of the video-based patient rounds must be taken into account.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the relatives who spent their time participating in the interviews and the staff of the cancer departments for allowing observation in the field and for making this study possible. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Vickie Svane Kristensen for language review of this article.

About the Author(s)

Lene Vedel Vestergaard, RN, MScN, and Christina Østervang, RN, MScN, are both research nurses in the Department of Oncology at Odense University Hospital in Denmark; Dorthe Boe Danbjørg, RN, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Haematology and in the Center for Innovative Medical Technology, both at Odense University Hospital, and in the Department of Clinical Research at the University of Southern Denmark in Odense; and Karin Brochstedt Dieperink, RN, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Oncology at Odense University Hospital, in the Department of Clinical Research at the University of Southern Denmark, and at the Danish Knowledge Centre of Rehabilitation and Palliative Care in Vestergade, Denmark. This work was funded by the AgeCare Academy of Geriatric Cancer Research and by the Foundation of Innovation, both at Odense University Hospital in Denmark. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Vestergaard and Østervang completed the data collection. Vestergaard can be reached at lene.vestergaard@rsyd.dk, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted December 2018. Accepted February 5, 2019.)

References

Aguiló, S., García, E., Arza, A., Garzón-Rey, J.M., & Aguiló, J. (2018). Evaluation of chronic stress indicators in geriatric and oncologic caregivers: A cross-sectional study. Stress, 21, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2017.1391211

Benzein, E., Johansson, P., Årestedt, K.F., & Saveman, B.I. (2008). Nurses’ attitudes about the importance of families in nursing care: A survey of Swedish nurses. Journal of Family Nursing, 14, 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840708317058

Yager, P.H., Clark, M., Cummings, B.M., & Noviski, N. (2017). Parent participation in pediatric intensive care unit rounds via telemedicine: Feasibility and impact. Journal of Pediatrics, 185, 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.02.054