Preserving Oneself in the Face of Uncertainty: A Grounded Theory Study of Women With Ovarian Cancer

Purpose: To describe the cancer care process as it is perceived by women with ovarian cancer.

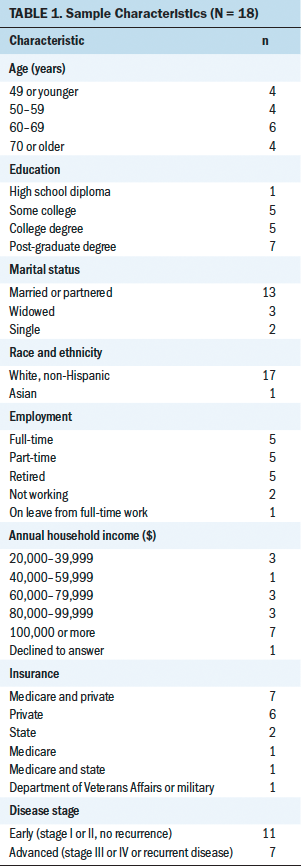

Participants & Setting: 18 English-speaking adult women with ovarian cancer were recruited from an advocacy organization for patients with ovarian cancer and the gynecologic oncology clinic at a community-based teaching hospital in Burlington, Massachusetts.

Methodologic Approach: A grounded theory approach was used. Data were collected via individual interviews with participants.

Findings: An overarching theme of preserving oneself in the face of uncertainty was described by the participants. Trajectories from prediagnosis to treatment were influenced by the quality of patient–provider communication, support from significant others, and self-concept aspects.

Implications for Nursing: Comprehensive care that validates patient concerns and supports information exchange is essential. Nurses can promote the physical and psychological well-being of women with ovarian cancer by identifying institutional and community-based resources for support and specialty care.

Jump to a section

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecologic malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women living in the United States (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2018). The overall five-year relative survival rate for ovarian cancer is 47%, which drops to only 29% for women who are diagnosed with late-stage disease (ACS, 2018). Although the development of novel cancer therapies, such as poly adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and immunotherapy, has been promising (Nelson & Jazaeri, 2017; Pujade-Lauraine, 2017), research indicates that the majority of women with ovarian cancer do not receive treatment in concordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (Champer et al., 2018; Warren et al., 2017). According to Bristow, Chang, Ziogas, and Anton-Culver (2013), guideline-concordant treatment is associated with improved overall survival rates for patients with cancer. Better understanding of the factors that influence the quality of ovarian cancer care can improve treatment and outcomes for patients and ensure that patients are receiving the maximum benefit from novel therapies.

In a systematic review of the determinants of guideline-concordant treatment of ovarian cancer, Pozzar and Berry (2017) determined that the majority of research on this topic has focused on identifying relationships between sociodemographic or clinical factors and care quality. Conversely, several studies have highlighted the need to explore patient, provider, and caregiver perspectives on decision making for ovarian cancer treatment (Pozzar, Baldwin, Goff, & Berry, 2018; Warren et al., 2017). Although several studies of women’s experiences living with ovarian cancer have been done (Burles & Holtslander, 2013; Ekwall, Ternestedt, Sorbe, & Sunvisson, 2014; Howell, Fitch, & Deane, 2003), women’s perceptions of the care process for ovarian cancer are largely undescribed. According to Donabedian (1988), the care process includes an individual’s “activities in seeking care and carrying it out,” as well as activities related to “making a diagnosis and recommending or implementing treatment” (p. 1,745). The pilot study by Pozzar et al. (2018) suggests that an exploration of the care process for ovarian cancer may provide additional insight into individual and contextual factors that influence treatment and patient outcomes. The purpose of this study was to describe the perceptions that women with ovarian cancer have of the cancer care process.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Northeastern University in Boston and the Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, both in Massachusetts. Participants were recruited from the Massachusetts chapter of a national advocacy organization for women with ovarian cancer and from the gynecologic oncology practice at a community-based teaching hospital in northeastern Massachusetts. Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and were able to speak and understand English. Interested participants were screened for eligibility by the principal investigator and provided informed consent prior to data collection. In remuneration for their participation in this study, participants received a $25 gift card.

Participants and Purposive Sampling

During the first phase of recruitment, six participants were recruited from the national advocacy organization. Three of the participants were aged 49 years or younger, and all had a college degree with an annual household income of $60,000 or more. During the second phase of recruitment, the investigators attempted to enroll participants whose characteristics differed in terms of age, education, and annual household income. Twelve participants were recruited from the gynecologic oncology practice during the second phase. Participants recruited during this phase were older on average, with a wider range of annual household incomes and educational backgrounds.

After analyzing two interviews with participants who were diagnosed with low-risk granulosa cell tumors, the investigators excluded potential participants with this diagnosis from further recruitment to ensure adequate representation of participants diagnosed with high-risk tumors. The final sample of 18 participants ranged in age from about 30 to 95 years and received cancer care from five different treatment facilities across eastern Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire (see Table 1).

Data Collection

Data were collected via individual interviews. The interview guide was based on a protocol developed by the authors and their colleagues for a pilot study that is described elsewhere (Pozzar et al., 2018). Interviews began with the opening prompt “Please tell me about your experience with ovarian cancer.” Participants were encouraged to speak freely in response to the initial prompt and subsequent probes. Prompts were used to facilitate further discussion once the participants’ initial accounts were complete; however, the interviewer discussed any topics raised by the participants throughout each interview. Interviews ranged from 40 to 90 minutes, with the average interview lasting about 60 minutes. As similar concepts emerged during the analysis, the list of prompts was refined and interviews became more structured to allow for the comparison of participant responses. The final list of prompts included the following topic areas:

• Establishing care with a provider or clinic

• Deciding on a treatment plan

• Communicating with providers

• Practical aspects of receiving treatment

• Symptoms and potential side effects of treatment

• Consideration of treatment efficacy

• Using complementary or alternative therapies

• Family or spousal issues

A verbal questionnaire was administered at the end of each interview to collect demographic information. Interviews were audio recorded, manually processed to remove any potential identifiers, and professionally transcribed. Transcripts were verified against deidentified audio recordings prior to analysis using NVivo Pro, version 11.0.

Data Analysis

Following the first interview, data gathering and analysis were conducted concurrently using grounded theory methods throughout the duration of the study (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). During analysis, selections of raw data representing the same underlying concept were assigned labels (open coding). Codes were developed and refined by comparing raw data within and between transcripts (constant comparison) to determine whether data labeled with the same code were conceptually similar or different. Codes were grouped into categories to identify preliminary relationships in data. Finally, a core category to which all other categories were related was identified. Throughout data analysis, the principal investigator maintained a record of her analysis and interpretation of the data in analytic memos and diagrams. The coinvestigator reviewed each step of analysis and was debriefed weekly by the principal investigator. A lay summary of the study’s conclusions was sent to participants, which allowed them to provide feedback on the findings (member checking).

Results

Thematic Results

The core theme identified during data analysis was preserving oneself in the face of uncertainty. Participants encountered a great deal of uncertainty during their experiences with cancer, beginning with symptom onset or recognition of an abnormality and persisting into survivorship. For some participants, survival statistics and recurrence rates increased alternating feelings of gratitude for survival and fear of subsequent testing. For other participants, feelings of uncertainty affected treatment decisions and characterized interpretations of physical symptoms even in the absence of disease. Some participants also experienced feelings of uncertainty in relation to social roles and self-image. Participants indicated that the core theme resonated with them in follow-up member checking.

For participants in this study, the feelings of uncertainty associated with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer represented a risk not only to their physical health, but also to their psychological well-being and self-concept. Given this risk, participants acted to preserve their sense of self. According to the results of this study, the actions of the participants had implications for the selection of cancer care providers, treatment decisions, and overall well-being during survivorship.

Patient–Provider Relationship

Communication with healthcare providers influenced participants’ experiences and decisions across the cancer continuum. Prior to diagnosis, participants engaged with healthcare providers primarily for evaluation of symptoms or incidental findings; however, following diagnosis, participants described how they relied on providers to convey information on treatment options and to provide anticipatory guidance. Participants described the extent to which care providers were compassionate and accessible, voicing appreciation for providers who validated their feelings and took their concerns seriously. Encounters with healthcare providers who were perceived as indifferent, inaccessible, or dismissive often prompted participants to act to preserve their physical or emotional health by seeking care elsewhere.

Compassion: Healthcare providers who were perceived as compassionate inspired the trust and confidence of participants, alleviating some of the emotional burdens associated with feelings of uncertainty. Having a foundation of trust in the patient–provider relationship often influenced participants’ decisions about from whom and where to receive care. Several participants who had an established relationship with a trusted provider described their reluctance to seek care elsewhere: “My daughter did suggest [going to the cancer center] here in [town]. I said, “No, I like [the physician] and I feel confident with her and I want to stay with her” (Participant 10). In addition, participants perceived compassionate providers to be largely invested in their treatment outcomes, and participants felt confident following the treatment recommendations made by these providers.

Participants who experienced a pattern of unsatisfactory communication encounters with their healthcare provider perceived the provider to be indifferent or lacking compassion. Indifference was often interpreted as a threat to one’s physical or emotional well-being. The actions taken by participants to remediate perceived threats to their sense of self varied. When providers were not believed to be invested in the participants or their care, participants described transferring to a healthcare provider who they viewed as more compassionate. Descriptions of this decision from participants suggest that finding a more compassionate provider served the dual purpose of ensuring that the provider would advocate for the best interests of the patient and would acknowledge the patient as a unique person instead of “a number.”

It began to feel . . . like an assembly line. Like, come in, number 1,024. Mark her off. Reminding me that I’m gonna die, just in case I didn’t catch it. I said, “If I go to another hospital, they may not be as well renowned, but maybe they will listen to me and maybe they’ll fight for me.” Because [at this hospital] . . . I feel like no one is fighting for me. They’re just waiting for me to die. (Participant 11)

In one case, when a participant’s desire for a compassionate provider conflicted with her need for a provider with a unique clinical skill set, she made a concession in the interest of her physical health.

I was really kind of appalled by how blunt [the surgeon] was. But I did get a chance to talk to one person he operated on. Four years later, [she] is still alive with no evidence of disease. I respect that his strengths are elsewhere. (Participant 3)

Accessibility: Healthcare providers who were perceived as accessible made participants feel comfortable asking questions during and outside of clinic visits. Participants described accessible providers as instrumental in providing information on disease characteristics, prognosis, treatment options, and test results. Positive information sharing was an essential component for participants in their pursuit of physical health. When information was received thoroughly and in a timely manner, participants were more confident in their providers and treatment plan; however, delayed or incomplete information led to participants reporting higher feelings of anxiety. Although some participants used the Internet as a resource for information, they reported finding information that was frightening, confusing, or not applicable to their unique circumstances. Consequently, some participants avoided seeking information outside of planned patient–provider encounters. Using this approach protected participants from overwhelming or frightening information, but it also limited the extent to which participants perceived that they were informed and could engage in treatment decisions. As one participant said, “[The gynecologic oncologist] said, ‘We can do this, we can do that, or we can do this. I recommend this.’ Well, you know, there’s really no choice, is there? I have no idea what I’m talking about” (Participant 11).

Participants appreciated healthcare providers who took them and their concerns seriously. Prior to diagnosis, providers who validated participant concerns were seen as proactive in facilitating initial diagnostic testing and subsequent referrals. However, some participants described feeling dismissed by providers prior to diagnosis and experienced continued delays in care throughout the course of treatment: “To have been dismissed—really, because that’s how I feel it was when I saw that first gynecologist—is very disconcerting. To think [that] I lost four months because of that is very upsetting” (Participant 18).

Throughout treatment, participants whose concerns were validated by providers perceived that they were free to express their values and preferences during discussions about treatment and follow-up care, as well as that providers would listen to them and act accordingly. In this context, participants could pursue improved physical health while also preserving autonomy. One participant stated, “I knew that there were a lot of downsides to [chemotherapy]. I felt confident that [the oncologist] would listen to me and that if those things happened, that we would stop” (Participant 4).

Support

Participants described the importance of receiving practical and emotional support throughout their experience with ovarian cancer. Participants reported that they received support from family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, healthcare providers, clergy members, and other cancer survivors. Those who received ample support alluded to the strength of their support network, whereas participants who had unmet support needs reported that they had to reevaluate interpersonal relationships and seek outside resources for support.

[My friends] never really reached out to me . . . so I reached out to [the hospital]. But they didn’t really have a support group for post-chemo patients. I just decided, “You know what, I’m gonna just deal with this myself.” I weeded out a lot of people. (Participant 17)

For participants who were dependent on family caregivers for transportation to medical appointments, inadequate support posed a threat to their overall physical health. Unmet emotional support needs were often described in the context of desiring contact with a fellow survivor. Nevertheless, participants who attended support groups reported that it was difficult to identify with survivors who were not the same age, were at a different life stage, had a different diagnosis or prognosis, or had care goals that did not align with the participant’s own goals. This finding is consistent with the belief that adequate support is essential to preserving physical and emotional well-being, as well as one’s notion of self.

Self-Concept

A diagnosis of ovarian cancer posed significant challenges to participants’ self-concepts. One participant described threats to her social role and self-image: “I sort of shy away from the idea of a disease presence as an identity, and that I’m a survivor. It’s just not who I kind of am” (Participant 4). In one example, a participant who described herself as a runner attributed her treatment decision making to her desire to maintain that aspect of her self-image:

I ran my first half marathon with the tumor inside me. I was 32, 33. I didn’t know how [chemotherapy] would affect my body. I was excited to get back into running afterwards, so I didn’t want to put that strain on [my body]. (Participant 6)

A diagnosis of ovarian cancer presented challenges to the participants’ social roles. Participants described the negative impacts of cancer on their careers and their financial situations. In addition, participants believed that their diagnosis changed how they were perceived by their colleagues. Participants who were mothers also suggested that ovarian cancer negatively affected their identity as a family caregiver. Relatedly, one participant described taking action to care for her family and to shelter family members from her experiences with cancer: “I wanted to keep it cool for my kids, and I think by going back to work as soon as I could, that kept my kids in a good frame [of mind]” (Participant 14).

Because a diagnosis of ovarian cancer could potentially threaten future familial aspirations, participants who hoped to preserve their fertility faced a unique challenge. When presented with the risk of losing fertility, one participant described undergoing a unilateral rather than bilateral oophorectomy, one described undergoing a radical hysterectomy while initiating the adoption process, and one described electing not to undergo chemotherapy after perceiving that the recommendations of her healthcare providers were ambiguous.

In some cases, participants experienced challenges with their social role but could not take action to mitigate it. One participant described the impact of treatment on her ability to function independently. This participant was newly dependent on a family caregiver for several activities of daily living and described adjusting to a new normal, as well as adopting a new self-concept to preserve her sense of self: “I’m used to getting in the car and going. And I can’t do that anymore. I can’t drive because of the neuropathy; I don’t dare” (Participant 8).

Finally, participants devoted considerable attention to the experience of losing their hair during chemotherapy treatment. Many participants dismissed the experience as “not [being] a big deal,” but others described the importance of finding a well-fitting wig and appreciated being referred to programs that are dedicated to helping women with cancer manage the appearance-related side effects of treatment. Although the fear of losing one’s hair did not affect treatment decisions among the participants in this sample, their efforts reflect their desire to maintain and preserve their self-image, which was threatened by their diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that women diagnosed with ovarian cancer engage in a care process to preserve their sense of self. Findings from previous research indicate that most women with ovarian cancer strive to preserve or restore their physical health through timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment (Elit et al., 2010; Frey et al., 2014; Havrilesky et al., 2014; Jolicoeur, O’Connor, Hopkins, & Graham, 2009; Lee et al., 2016). Similarly, feelings of uncertainty surrounding a diagnosis of ovarian cancer have been characterized in the literature (Beesley et al., 2013; Kornblith et al., 2010). The current study adds to the existing literature by highlighting several contexts in which women with ovarian cancer may prioritize outcomes other than survival, remission, or cure. In this study, participants made decisions that allowed them to preserve or restore not only their physical health, but also their psychological well-being, self-concept, self-image, and social role.

According to the results of this study, participants’ experiences with patient–provider communication influenced practical decisions about cancer care, physical health, and psychological well-being. In previous studies of women with ovarian cancer, communication with a trusted healthcare provider played a role in provider selection (Pozzar et al., 2018), information sharing (Ekwall, Ternestedt, Sorbe, & Graneheim, 2011; Elit et al., 2010; Gleeson et al., 2013), and engaging in one’s care (Elit et al., 2010; Fitch, Deane, & Howell, 2003). Inadequate information has been identified as a barrier to participation in treatment decisions for ovarian cancer (Ekwall et al., 2011; Ziebland, Evans, & McPherson, 2006), a result that is supported by the challenges faced by women with ovarian cancer in this study who pursued information on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment outside of the patient–provider relationship. However, ovarian cancer care providers face their own challenges with information sharing (Elit et al., 2012) and may be influenced by assumptions about patient understanding or the level of involvement women with ovarian cancer wish to have with their care (Elit, Charles, & Gafni, 2015; Elit et al., 2015). The finding that unsatisfactory communication encounters may influence care decisions highlights the need for additional research on patient–provider communication in the ovarian cancer care setting.

Participants in this study emphasized the role of support in preserving the self. According to Berkman (1984), social roles provide individuals with a sense of belonging and often influence physical and psychological well-being. In a study by Keim-Malpass et al. (2017), higher social support was associated with fewer physical and psychosocial problems over time, whereas Lutgendorf et al. (2012) suggest an association between social attachment and survival. Staneva, Gibson, Webb, and Beesley (2018) describe dissatisfaction with formal support resources among women with ovarian cancer. The results of this study can influence understanding of the potential ramifications of unmet support needs in this population and encourage the development of improved interventions.

According to the literature, threats to social role and self-image may result from changes in physical appearance (Münstedt, Manthey, Sachsse, & Vahrson, 1997; Schaefer, Ladd, Lammers, & Echenberg, 1999), loss of fertility (Schaefer et al., 1999), changes in physical functioning (Norton et al., 2005), and changes in employment (Moffatt & Noble, 2015) following cancer treatment. In a qualitative study of ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences with self-advocacy, Hagan and Donovan (2013) use the theme of “knowing who I am and keeping my psyche intact” (p. 144) to emphasize the importance of identity and preserving the self. Norton et al. (2005) found that greater physical impairment and greater change in body image following cancer treatment were associated with lower perceived control over ovarian cancer, leading to greater psychological distress. In a large-scale study of reproductive-age women with cancer, pretreatment fertility counseling led to improved quality of life following treatment (Letourneau et al., 2012). Additional research is needed to identify best practices for clinicians to assist women with ovarian cancer in managing threats to self-concept and to determine whether such interventions can alleviate distress and improve patient outcomes.

The care process described by participants in this study is congruent with the desired outcomes outlined in models of patient-centered care. According to the Institute of Medicine (2001), patient-centered care is “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values” (p. 3). Patient-centered communication is informative, empathetic, and considers the person with cancer within his or her unique psychological and social context (Epstein & Street, 2011). In the cancer care setting, patient-centered communication has been identified as a potential determinant of quality care (Epstein & Street, 2007), and the findings of this study highlight the need for additional research regarding the influence of patient-centered care on ovarian cancer treatment and patient outcomes.

Limitations

Although this study included the perspectives of participants from several different clinical and sociodemographic groups, only one participant was not White and non-Hispanic. As a result, the perspectives of women with ovarian cancer from various racial and ethnic backgrounds may not be represented by the conclusions of this study. Because this study was conducted with participants receiving cancer care in a region of the United States with a high concentration of gynecologic oncologists and academic medical centers, the experiences of women without access to specialty care or women in rural settings may differ from the experiences described in this study. Because of the potential for racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in ovarian cancer treatment (Bristow et al., 2015; Hodeib et al., 2015), exploration of these themes in a larger, more diverse sample is warranted. Finally, the qualitative nature of this study dictates that these findings cannot be generalized to a broader population without additional research.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses can assist women with ovarian cancer to identify and address their needs for maintaining physical health, psychological well-being, and self-concept. In addition, nurses can promote a therapeutic relationship between healthcare providers and patients by providing compassionate care that validates patient concerns and supports information exchange and understanding. During initial assessments, nurses can ask patients to describe their treatment goals, the extent to which they are supported emotionally and practically, and the effect of ovarian cancer and its treatment on their social roles and self-image. Care plans for women with ovarian cancer should include identifying and interpreting educational materials; establishing institutional- and community-based resources for financial or emotional support; and engaging in interprofessional collaboration to facilitate access to specialists who can provide behavioral health services, fertility counseling or preservation, or management for side effects of treatment. The findings from this study indicate that information exchange and patient-centered care are important aspects of the experience of having cancer and the process by which women with ovarian cancer make care decisions; therefore, nurse scientists can develop education and communication interventions to facilitate these aspects in the ovarian cancer care setting.

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest that although women with ovarian cancer are motivated to preserve their physical health, psychosocial factors, such as communication, support, and self-concept, may also affect decision making. To ensure that patient-centered care is a priority in the ovarian cancer care setting, these findings can inform future efforts to promote guideline-concordant treatment and the adoption of novel treatment therapies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Valena Wright, MD, and Allison Matthews, BA, for their assistance with recruitment.

About the Author(s)

Rachel A. Pozzar, PhD, RN, FNP-BC, is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Phyllis F. Cantor Center for Research in Nursing at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA; and Donna L. Berry, PhD, RN, FAAN, AOCN®, is a nurse scientist in the Phyllis F. Cantor Center for Research in Nursing at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and a professor of biobehavioral nursing and health informatics in the School of Nursing at the University of Washington in Seattle. This research was supported by a doctoral degree scholarship in cancer nursing (130725-DSCN-17-080-01-SCN) from the American Cancer Society and the Jonas Philanthropies Nurse Scholars Initiative. Both authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Pozzar completed the data collection. Pozzar can be reached at rpozzar@partners.org, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted January 2019. Accepted February 26, 2019.)

References

American Cancer Society. (2018). Cancer facts and figures, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and…

Beesley, V.L., Price, M.A., Webb, P.M., O’Rourke, P., Marquart, L., & Butow, P.N. (2013). Changes in supportive care needs after first-line treatment for ovarian cancer: Identifying care priorities and risk factors for future unmet needs. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1565–1571. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3169

Berkman, L.F. (1984). Assessing the physical health effects of social networks and social support. Annual Review of Public Health, 5, 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002213

Bristow, R.E., Chang, J., Ziogas, A., & Anton-Culver, H. (2013). Adherence to treatment guidelines for ovarian cancer as a measure of quality care. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 121, 1226–1234. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182922a17

Bristow, R.E., Chang, J., Ziogas, A., Campos, B., Chavez, L.R., & Anton-Culver, H. (2015). Sociodemographic disparities in advanced ovarian cancer survival and adherence to treatment guidelines. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 125, 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000643

Burles, M., & Holtslander, L. (2013). “Cautiously optimistic that today will be another day with my disease under control”: Understanding women’s lived experiences of ovarian cancer. Cancer Nursing, 36, 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e318277b57e

Champer, M., Huang, Y., Hou, J.Y., Tergas, A.I., Burke, W.M., Hillyer, G.C., . . . Wright, J.D. (2018). Adherence to treatment recommendations and outcomes for women with ovarian cancer at first recurrence. Gynecologic Oncology, 148, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.11.008

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA, 260, 1743–1748. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

Ekwall, E., Ternestedt, B.M., Sorbe, B., & Graneheim, U.H. (2011). Patients’ perceptions of communication with the health care team during chemotherapy for the first recurrence of ovarian cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.06.001

Ekwall, E., Ternestedt, B.M., Sorbe, B., & Sunvisson, H. (2014). Lived experiences of women with recurring ovarian cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2013.08.002

Elit, L., Charles, C., Dimitry, S., Tedford-Gold, S., Gafni, A., Gold, I., & Whelan, T. (2010). It’s a choice to move forward: Women’s perceptions about treatment decision making in recurrent ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1562

Elit, L., Charles, C., Gafni, A., Ranford, J., Gold, S.T., & Gold, I. (2012). Walking a tightrope: Oncologists’ perspective on providing information to women with recurrent ovarian cancer (ROC) during the medical encounter. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 2327–2333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1344-0

Elit, L., Charles, C.A., & Gafni, A. (2015). Oncologists’ perceptions of recurrent ovarian cancer patients’ preference for participation in treatment decision making and strategies for when and how to involve patients in this process. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 25, 1717. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000548

Elit, L.M., Charles, C., Gafni, A., Ranford, J., Tedford-Gold, S., & Gold, I. (2015). How oncologists communicate information to women with recurrent ovarian cancer in the context of treatment decision making in the medical encounter. Health Expectations, 18, 1066–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12079

Epstein, R.M., & Street, R.L., Jr. (2007). Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering (NIH Publication No. 07-6225). Retrieved from https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/docs/pcc_monograph.pdf

Epstein, R.M., & Street, R.L., Jr. (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 100–103. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1239

Fitch, M.I., Deane, K., & Howell, D. (2003). Living with ovarian cancer: Women’s perspectives on treatment and treatment decision-making. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 13, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.5737/1181912x131813

Frey, M.K., Philips, S.R., Jeffries, J., Herzberg, A.J., Harding-Peets, G.L., Gordon, J.K., . . . Blank, S.V. (2014). A qualitative study of ovarian cancer survivors’ perceptions of endpoints and goals of care. Gynecologic Oncology, 135, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.008

Gleeson, M., Meiser, B., Barlow-Stewart, K., Trainer, A.H., Tucker, K., Watts, K.J., . . . Kasparian, N. (2013). Communication and information needs of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer regarding treatment-focused genetic testing. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.ONF.40-03AP

Hagan, T.L., & Donovan, H.S. (2013). Ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy: A focus group study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.ONF.A12-A19

Havrilesky, L.J., Alvarez Secord, A., Ehrisman, J.A., Berchuck, A., Valea, F.A., Lee, P.S., . . . Reed, S.D. (2014). Patient preferences in advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer, 120, 3651–3659. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28940

Hodeib, M., Chang, J., Liu, F., Ziogas, A., Dilley, S., Randall, L.M., . . . Bristow, R.E. (2015). Socioeconomic status as a predictor of adherence to treatment guidelines for early-stage ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology, 138, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.04.011

Howell, D., Fitch, M.I., & Deane, K.A. (2003). Women’s experiences with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Nursing, 26, 10–17.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Jolicoeur, L.J., O’Connor, A.M., Hopkins, L., & Graham, I.D. (2009). Women’s decision-making needs related to treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer: A pilot study. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 19, 117–121. https://doi.org/10.5737/1181912x193117121

Keim-Malpass, J., Mihalko, S.L., Russell, G., Case, D., Miller, B., & Avis, N.E. (2017). Problems experienced by ovarian cancer survivors during treatment. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 46, 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.04.134

Kornblith, A.B., Mirabeau-Beale, K., Lee, H., Goodman, A.K., Penson, R.T., Pereira, L., & Matulonis, U.A. (2010). Long-term adjustment of survivors of ovarian cancer treated for advanced-stage disease. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 28, 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2010.498458

Lee, J.Y., Kim, K., Lee, Y.S., Kim, H.Y., Nam, E.J., Kim, S., . . . Kim, Y.T. (2016). Treatment preferences of advanced ovarian cancer patients for adding bevacizumab to first-line therapy. Gynecologic Oncology, 143, 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.021

Letourneau, J.M., Ebbel, E.E., Katz, P.P., Katz, A., Ai, W.Z., Chien, A.J., . . . Rosen, M.P. (2012). Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer, 118, 1710–1717. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26459

Lutgendorf, S.K., De Geest, K., Bender, D., Ahmed, A., Goodheart, M.J., Dahmoush, L., . . . Sood, A.K. (2012). Social influences on clinical outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 2885–2890. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4411

Moffatt, S., & Noble, E. (2015). Work or welfare after cancer? Explorations of identity and stigma. Sociology of Health and Illness, 37, 1191–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12303

Münstedt, K., Manthey, N., Sachsse, S., & Vahrson, H. (1997). Changes in self-concept and body image during alopecia induced cancer chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 5, 139–143.

Nelson, B.H., & Jazaeri, A.A. (2017). Immunotherapy for gynecological cancers: Opportunities abound. Gynecologic Oncology, 145, 411–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.05.003

Norton, T.R., Manne, S.L., Rubin, S., Hernandez, E., Carlson, J., Bergman, C., & Rosenblum, N. (2005). Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: The role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychology, 24, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.143

Pozzar, R., Baldwin, L.M., Goff, B.A., & Berry, D.L. (2018). Patient, physician, and caregiver perspectives on ovarian cancer treatment decision making: Lessons from a qualitative pilot study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-018-0283-7

Pozzar, R.A., & Berry, D.L. (2017). Patient-centered research priorities in ovarian cancer: A systematic review of potential determinants of guideline care. Gynecologic Oncology, 147, 714–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.004

Pujade-Lauraine, E. (2017). New treatments in ovarian cancer. Annals of Oncology, 28(Suppl. 8), viii57–viii60. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx442

Schaefer, K.M., Ladd, E.C., Lammers, S.E., & Echenberg, R.J. (1999). In your skin you are different: Women living with ovarian cancer during childbearing years. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121802

Staneva, A.A., Gibson, A.F., Webb, P.M., & Beesley, V.L. (2018). The imperative for a triumph-over-tragedy story in women’s accounts of undergoing chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 28, 1759–1768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318778261

Warren, J.L., Harlan, L.C., Trimble, E.L., Stevens, J., Grimes, M., & Cronin, K.A. (2017). Trends in the receipt of guideline care and survival for women with ovarian cancer: A population-based study. Gynecologic Oncology, 145, 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.016

Ziebland, S., Evans, J., & McPherson, A. (2006). The choice is yours? How women with ovarian cancer make sense of treatment choices. Patient Education and Counseling, 62, 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.014