In Their Own Words: Experiences of Caregivers of Adults With Cancer as Expressed on Social Media

Purpose: To explore caregivers’ writings about their experiences caring for adult individuals with cancer on a social media health communication website.

Participants & Setting: Journal entries (N = 392) were analyzed for 37 adult caregivers who were posting on behalf of 20 individuals with cancer. CaringBridge is a website used by patients and informal caregivers to communicate about acute and chronic disease.

Methodologic Approach: A retrospective descriptive study using qualitative content analysis of caregivers’ journal entries from 2009 to 2015.

Findings: Major categories identified in caregivers’ online journals included patient health information, cancer awareness/advocacy, social support, caregiver burden, daily living, emotions (positive and negative), and spirituality.

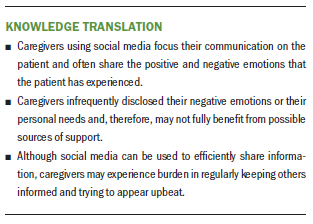

Implications for Nursing: Nurses often recommend using social media as a communication strategy for patients with cancer and their caregivers. The findings from this study provide potential guidance nurses may wish to offer caregivers. For example, nurses may talk with caregivers about how and what to post regarding treatment decisions. In addition, nurses can provide support for caregivers struggling with when and how often to communicate on social media.

Jump to a section

More than 1.7 million people in the United States were diagnosed with cancer in 2018 (American Cancer Society, 2018). Most of these individuals will, at some point, require the help of a family caregiver who volunteers to provide unpaid care to patients (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). A family caregiver is described by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016) as someone who takes on a helping role to an ill individual. Caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer are often women and aged 55 years and older (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2019).

Caregiving roles and tasks vary based on the individual’s cancer diagnosis, symptoms, and comorbidities (Ellis, 2012; van Ryn et al., 2011). Caregivers may be involved in assisting the patient with activities of daily living (Saria et al., 2017) and financial and household tasks, helping the patient to navigate the healthcare system, providing symptom management, and monitoring for side effects (DuBenske et al., 2008; Given, Given, & Sherwood, 2012; Gofton, Graber, & Carter, 2012; Saria et al., 2017; Shaw et al., 2013). Caregivers may alter their work life and experience financial and legal stressors during times of transition (DuBenske et al., 2008). The emotional toll can result in depression and anxiety (Lambert, Girgis, Lecathelinais, & Stacey, 2013; Saria et al., 2017).

Having good support can help ameliorate the negative effects of caregiving, and social media is an avenue where many caregivers look for support. The use of social media for general communication and, specifically, for health-related information and communication is increasing (Prestin, Vieux, & Chou, 2015). Caregivers are at the forefront of health-related users, and they use social media in great numbers (Pew Research Center, 2013). Several social media sites, such as CaringBridge, specifically focus on supporting patients and families during a health event. Individuals document in a journal format similar to personal cancer blogs. Research related to social media use found that patients and families feel they benefit from the emotional and spiritual support offered by visitors to these sites, appreciate the convenience of communicating to groups of people quickly, and easily connect with individuals with similar experiences and diagnoses (Anderson, 2011; Bender et al., 2012; Bender, Jimenez-Marroquin, & Jadad, 2011; Kim & Chung, 2007; Lapid et al., 2015). A few studies have examined what caregivers share on social media. Their findings include sharing caregiver burdens (Gage-Bouchard, LaValley, Mollica, & Beaupin, 2017), promoting cancer awareness/advocacy (Gage-Bouchard et al., 2017), requesting information and tangible support (Gage-Bouchard et al., 2017; Lu, Wu, Liu, Li, & Zhang, 2017), and sharing emotions (Lu et al., 2017). Gage-Bouchard et al. (2017) examined Facebook postings, and Lu et al. (2017) examined an online breast cancer support group.

Little is known about how caregivers use CaringBridge and other similar sites. Because the focus of CaringBridge is on the patient, caregivers may or may not choose to write about their own experiences. Caregivers may fear being judged or criticized by their social network, so they may limit how much they share (Family Caregiver Alliance [FCA], 2014; Lepore & Revenson, 2007). Because they fear judgment by their social network, sharing emotions may be difficult for caregivers (FCA, 2014). Individuals may anticipate or perceive social constraints from their network in the form of criticism and disapproval (Lepore & Revenson, 2007). Many online resources for caregivers highlight the anger, guilt, shame, frustration, and other negative emotions caregivers often feel but are afraid to share (FCA, 2014; Jacobs, 2017; NCI, 2014). Lu et al. (2017) compared the sharing of emotions between patients and caregivers on social media and found that patients were more likely to share emotions than caregivers.

The model of social support elicitation and provision guided the aim of this project (Wang, Kraut, & Levine, 2015). A key tenet of this model is that what an individual writes or discloses on social media can affect the social support they receive. Wang et al. (2015) proposed that self-disclosure may lead others to perceive emotional needs and provide emotional support, and that asking questions may lead others to perceive informational needs and provide informational support. The study informing this model found that both the perceptions of the network and what individuals write affects the type of social support received. These assumptions were at the foundation of this research. CaringBridge and similar sites are designed to assist patients and caregivers with sharing their experiences and to bring social support to patients and caregivers; however, there is a lack of research examining caregivers’ experiences with the social support offered on these sites. In addition, posting on the site itself could be burdensome to caregivers because they may feel that they are the source of information to all site viewers.

In this study, the authors examined how adult caregivers work within the framework of a social media site dedicated to the adult individual with cancer. The research questions guiding this study were: How are the activities of caregiving described by the caregivers? Do caregivers write about the psychosocial impacts of the cancer diagnosis on themselves? And, if so, what do they write about? Increased understanding of the caregiver experience can help nurses identify caregivers’ needs, create social media interventions to meet those needs, and prevent the spread of misinformation (Kent et al., 2016).

Methods

A retrospective descriptive qualitative design was used to conduct content analysis of CaringBridge sites, specifically the journal entries written by adult caregivers. CaringBridge had a total of 31 million unique visitors in 2018 (CaringBridge, 2018a). The individual websites are centered on the patient, although, in the case of CaringBridge, caregivers are most commonly the site administrators (K. Palmstein, personal communication, April 23, 2013). CaringBridge sites are created by patients and/or families to communicate and allow others to follow the cancer journey. Individual sites contain multiple written entries (including a short biography), journal entries in which caregivers and patients write about their cancer experiences, guest posts in which guests write to the patient and/or caregivers, and a planner in which caregivers and patients can coordinate care needs with guests. The focus and the content analysis of the current study was on the caregivers’ writings within the journal entries for selected cases.

Only low-privacy, open-access CaringBridge sites were included in the analysis. CaringBridge privacy settings at the time of the study included low-privacy sites that the public could view without logging onto CaringBridge or receiving an invitation from the site administrator (CaringBridge, 2018b). Low-privacy sites comprised about 30% of all CaringBridge sites (K. Palmstein, personal communication, April 23, 2013). Because publicly available data were used, this study was determined to be nonhuman subjects research by the University of Utah’s institutional review board.

Case Selection

The rationale for the case selection was for purposes of increasing sample diversity. In addition, cases needed to be searchable within the parameters of the CaringBridge search engine. Two separate processes were tested in an unpublished pilot study: personal surnames and geographic regions. First, a search by surname was implemented. The plan was to search for eligible cases by first searching for cases matching selected surnames and then examining the content of each case to see if it met the eligibility criteria. This attempt was designed to yield a diverse sample. The initial search used last names from U.S. Census Bureau (2013) data with the greatest likelihood of surname by race and Hispanic origin (Word, Coleman, Nunziata, & Kominski, n.d.). The top two surnames most closely linked to race/ethnicity were used for the search. Names for American Indians/Alaskan Natives were excluded, as no names were more than 4% likely to correlate with race (Word et al., n.d.). Of the 328 cases identified, 197 were excluded because the surname searched was the patient’s first name or a city name. For example, when searching for Washington (the most likely African American surname), CaringBridge’s search engine provided cases with the last name Washington but also provided results for individuals with different surnames who lived in Washington, DC. Case selection using names most highly associated with race/ethnicity yielded poor results, with only three cases meeting the eligibility criteria for the pilot study. It was determined, based on the search findings, that it would be difficult to identify racially diverse sites.

A second search was developed based on the four regions of the United States as designated by the U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.): Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. The largest city, by population, was chosen for each region to increase the likelihood of having more racially diverse cities included in the sample; however, the limitation of this search was that the sample did not include rural areas, and all races/ethnicities still might not have been present at the sites sampled. Cities were found to be searchable during the previous case selection using surnames. Using the largest city in each of the four census-defined geographic regions (i.e., Northeast: New York, NY; South: Houston, TX; Midwest: Chicago, IL; West: Los Angeles, CA) was a successful strategy and yielded 95 cases meeting the pilot study’s eligibility criteria. Because this was a successful strategy for the pilot, it was used as the search strategy for this study and 398 potential cases were identified using this method.

Despite using city names for the search, cases were from cities other than the search terms used. The mismatched cities were related to limitations of the search function of CaringBridge; the search functionality was created to identify names of individuals and not to search for cities.

Each case consisted of journal entries by the caregiver or caregivers of an individual diagnosed with cancer. Some cases had more than one caregiver writing the journal entries. Eligible CaringBridge cases met the following criteria: the individual with cancer and/or caregiver had selected open settings with no restrictions (i.e., open access), postings were written in English, the patient was aged 21 years or older (when patient age could not be determined, the case was not used), the patient had a cancer diagnosis, at least one patient caregiver (including family and friends of the patient) must have written the majority of the journal entries, and cases must have been created at least six months prior to the study start date to ensure sufficient data were available. Patients’ journal entries were excluded from this analysis because the focus of the study was on the caregivers’ experiences. Caregivers’ journal entries were identified by examining each journal entry for the sign-in name (the individual identified on the website as the writer of the journal entry), who signed the text of the journal entry, and/or the use of pronouns (e.g., use of he/she to describe the patient rather than I/me). The sign-in name did not always reflect who wrote the posting (i.e., some caregivers posted under the patient login), so the other identifiable information provided was used to ascertain the author.

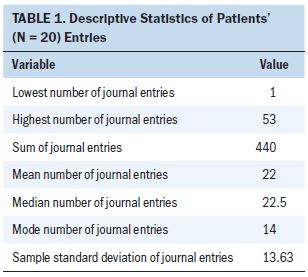

Of the 398 cases found using the search terms, 69 met the criteria; each case contained multiple journal entries. Eight of the 69 cases were previously analyzed in a pilot study (unpublished) and, therefore, were excluded. For the 61 cases remaining, the number of journal entries per case ranged from 1 (this one journal entry was multiple entries added to the same entry and covered about four weeks of time) to 255 (mean = 50, SD = 56.3) (see Table 1). Because of the large amount of content available in the 61 cases, 11 cases were excluded because the volume of the journal entries and/or guestbook postings were greater than 1 standard deviation from the mean number of journal entry and guestbook postings (for example the largest case had more than 255 journal entries and 2,318 guestbook postings). Because the data were skewed to the right, none of the sites was less than 1 standard deviation from the mean. This left 50 cases to be examined, and each of the cases were given an identifying number ranging from 1 to 50. Then, a random sample online tool (www.randomizer.org/form.htm) was used to select a smaller subset of 20 cases. The random sampler was used so the principal investigator would not be biased in her selection of the sites examined. Once the 20 cases were selected, no additional cases were removed/excluded. The authors ended up with an equal distribution across all four census areas by chance. Within the 20 cases, there were a total of 440 journal entries available; however, because the focus of the study was on caregivers, only the 392 caregiver entries were examined.

Journal entries were collected in March and April 2016; therefore, only data from prior to those dates were included in this study. The 20 cases examined included entries from 2009 to 2015 (the larger data set of 61 cases included dates from 2007 to 2016). Most entries included in this analysis occurred from 2012 to 2013. Fifteen of the 20 cases used CaringBridge for a few months to one year. Five cases had writings spanning more than one year.

Demographic Variables Collected

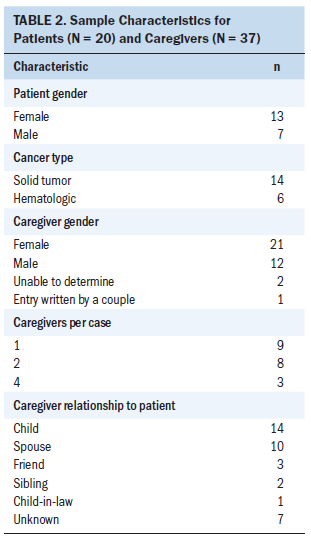

Demographic data were collected based on what was available in CaringBridge. The characteristics collected included role of the writer (patient or caregiver), patient’s cancer type, patient gender, caregiver gender, and caregivers’ relationship to patient (see Table 2).

Content Analysis

Journal entries were captured and downloaded into NVivo, version 11, software from the CaringBridge website. The unit of analysis was each entry written by a caregiver. Using a conventional content analysis framework, primary coding was completed in two phases: first cycle coding using descriptive coding and second cycle coding using pattern coding (Saldaña, 2016). For the first case, one researcher (RDB) read each entry from beginning to end. During the first reading, notes were taken on patterns, topics, and themes, and open coding was used to create a set of preliminary descriptive codes (nodes) and sub codes (Saldaña, 2016). An inductive process was used for category development (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). After review and coding of all caregiver journal entries for the first case, six subsequent cases were reviewed and new codes (nodes) were added until no new codes were identified. Overlapping codes were permitted, meaning the same text could be double coded. After preliminary coding was completed, the second round of coding began, in which codes were either combined or split, based on the data, until a final set of parsimonious and meaningful codes were determined (Saldaña, 2016). During this phase of coding, expert review was provided by several of the researchers (SB, WSC, and LE) to ensure cogent categories were created and a final manual was created to aid in additional coding.

Rigor

Interrater reliability was assessed by having a second experienced coder independently code a subset of the 20 cases using a coding manual (Lombard, Snyder-Dutch, & Bracken, 2002). The subset was randomly selected to ensure no researcher biases were present in the selection of journal entries and included 10% (n = 44) of caregiver journal entries. The primary coder provided initial training to the secondary coder, then each coder coded the same 44 journal entries independently (Holman, 2017). Intermittent check-ins were conducted to ensure each coder was consistent throughout the coding process (Holman, 2017). Upon initial comparison of codes, the reviewers had a Cohen’s kappa for percent agreement of 0.715, which is acceptable (Lombard et al., 2002). Any disagreements in coding were evaluated by both coders to find agreement (Holman, 2017). During the evaluation, the reviewers removed or added codes to their existing coding. Most of the changes made were to add a code that one reviewer had coded but the other had not identified on their first pass of coding. In addition, some codes were removed as both coders came to agreement that the code was not appropriate per the coding manual. The primary reviewer then coded any remaining journal entries based on the decisions made to find agreement.

Findings

Demographic Characteristics

Caregivers described the disease in their own words; therefore, specific medical diagnoses were not always provided. However, it appeared that multiple types of cancers were represented. In total, 37 caregivers wrote on the 20 sites on behalf of the patients. Most caregivers were women (n = 21), and caregivers wrote most of the journal entries (n = 380). The patient died in 10 of the 20 cases.

Categories

The focus of the study was to examine what caregivers wrote about the cancer experience (disclosure) and their experiences as caregivers. Seven main categories of ways caregivers described their experiences or the experiences of the patient were identified: patient health information, cancer awareness/advocacy, social support, caregiver burden, daily living, emotions (positive and negative), and spirituality. Many categories tied in closely with one another, often overlapping. For example, while describing patients’ plans of care, caregivers were often positively focused and hopeful about the outcomes of treatment, so the categories of both sharing patient health information and positive emotions were present. Positive and negative emotions were also seen when caregivers described their daily lives.

Sharing Patient Health Information

Caregivers shared information on patients’ care, symptoms, and side effects. Much of the focus of their entries was on sharing the patient’s plans of care. This included describing appointments and conversations with providers. One caregiver shared that the doctor “is still talking about doing experimental treatment. It sounds like he is really going to push that as soon as we get through the next few weeks and repeat the CT of abdomen.” They wrote about when the patient was hospitalized and discharged to home. Caregivers focused on describing treatments and tests, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, procedures (e.g., port placement, colonoscopy, biopsy), imaging tests, laboratory tests, and surgeries. The caregivers often wrote about these tests in a straightforward description.

She was then scheduled for an MRI of the brain to find out what was causing her headaches, also scheduled for ultrasound of abdomen and CT scan of her abdomen.

Caregivers wrote about upcoming plans, delays, and results, and described the patient’s health status. They shared anticipated side effects as well as side effects and symptoms experienced by the patient.

My mother has round two of chemo this upcoming Tuesday the 9th. She is not looking forward to [this] obviously as they say the side effects will be progressively worse as time goes on and she does more chemo.

She started feeling really tired after her hair appointment. When they got home, her blood oxygen level had fallen enough that dad put her oxygen back on. She slept with the oxygen all night. The next afternoon, we still couldn’t keep it at a comfortable level, so dad and I knew we needed to take her back to the hospital.

In several cases, they wrote about stopping treatment and determining whether to go on hospice care.

My mom is in the hospital right now. She went to the ER last night and was admitted in. They are trying to make her comfortable and monitor a few things that they were concerned about last night. She’ll most likely be home on Monday. When she comes home hospice will be here to begin their service of making sure my mom’s quality of life is the best it can be, and she remains comfortable. She will not be continuing with any treatment other than controlling her pain and discomfort.

As they shared these plans, they often described their role in the plan (e.g., taking the patient to their appointments) or discussions they participated in.

Promoting Cancer Awareness and Advocacy

A small subset of caregivers used CaringBridge to promote cancer awareness and advocacy. They encouraged others to get a checkup when something was wrong, and to share their story so others could learn from it.

The real reason I wanted to share this here is to say listen to your own body and if something doesn’t seem right don’t ignore it. Bumps, lumps and the occasional night sweat don’t always mean something’s wrong, but they can mean something’s wrong—it’s worth the $25 co-pay to find out for sure.

They promoted websites to donate to cancer causes. One caregiver even shared a website to help others identify fake cancer cures.

We’re sure many of you have heard a lot of the “cancer cures” from well-meaning friends and family. Unfortunately there is everything from snake oil salesmen to faith healers to charlatans to conspiracy theorists with a product, and everyone is sincere. We are still trying to double check everything just to be sure we are doing everything possible to beat this cancer. I have found that rather than trying to read the reams of information about a particular “cure,” I first see if it meets certain standards. Here is a [website] that helps: http://bit.ly/2ZHelF7.

These caregivers recognized they had the ability to reach their guests and used their platform as a source of information and to prevent the spread of misinformation.

Social Support

This category included caregivers’ requests for support as well as support received. Caregivers requested support from CaringBridge guests in several ways, mostly on behalf of the patient, but rarely for themselves. Common requests were for prayers, but caregivers also asked guests to visit the patient.

Pray for her this week as she undergoes surgery for her port. And that it will be healed enough by Monday that it won’t be too painful for her next round of chemo.

So, asking family and friends to watch over her while I’m gone, she really doesn’t want to go back in the hospital so if you can get there to see her we would both appreciate it.

A limited number of caregivers requested additional support for meals, transportation to and from appointments, and financial support.

The family really appreciates help with dinner for D.B., S.B., and R.B. A meal assistance schedule has been arranged, and there are plenty of slots available (and more will open in September).

As for those asking what they can do to help . . . right now, we have the next week or so of appointments covered. I really need help getting my mom food throughout the day.

A small subset of caregivers requested information for clinical and nonclinical needs.

She feels OK but since our white blood cells are the disease fighting cells in our bodies, when they’re low, we are more prone to get sick or fight illness, so the dose of chemo wouldn’t work as well as it should during this time. (If you’re reading this and have a better explanation, please chime in because this is all new to me).

She will have a DVD player in her room in the hospital—We would love any suggestions for fun/funny movies we can rent for her during her stay!

Caregivers used entries to offer encouragement and compliment the patient.

L.T. is the strongest woman I know, and my life would be absolutely lost without her.

I know mom will give this infection a run for its money.

R.S., you look beautiful to me!

He had a head shaving party yesterday and is proving that bald is beautiful, or in his case, handsome.

Caregivers also wrote about support received, including prayers and encouragement, visits, meals provided to the family, and friends and other caregivers aiding in the care of the patient. “T.S. has been here and helped empty the old house, and S.L. comes Thursday to help. E.S. and C.S. have also done their parts.”

Caregiver Burden

Burdens described included financial stress, dealing with non-cancer stressors, schedule changes, health concerns, and alleviating concerns of their guests. Caregivers’ expenses included the costs of traveling to care for the patient.

The driving back and forth is going to get expensive. . . . I feel torn—I want to stay but need to go home for a little bit too . . . the kids need it . . . we all need it.

They often mentioned non-cancer stressors, such as moving to a new home or caring for other sick family members.

On a good note, we have moved to our new townhouse. It wasn’t easy but we did it and I think it was a good decision as our master bedroom is on the first floor.

Meanwhile our Dad has lost his significant other of 40 plus years and lives alone now, which has been a concern to us as he is 86 years old and not so steady on his feet. He lives on a hill and has to go down the hill to get to his car. He has rolled down that hill a few times I might add. So we are busy getting Lifeline for him and some handicap bars in his bathroom.

Schedule changes included rearranging their schedule or being unable to find time to take patients to all the necessary appointments.

I leave for school before she is up and I’m trying to be here as much as possible, but I am expected to be at work.

Another full day at the clinic. Some of you are asking when the transplant date is. Well this is what we know as of yesterday. Met with transplant coordinator in the am and she said L.P. would go in the hospital [Saturday] and start chemo. By afternoon that had changed to the following [Wednesday].

Caregivers described difficulties in planning their day because appointments were not always on time or shorter or longer than planned.

Yesterday, T.S. and I had big plans. We were going to go to the mall and walk and maybe shop a little. I took her to her appt. at 8:30 and she didn’t get done until 2 pm.

Caregivers rarely discussed their own health, but, when they did, it was in relation to how it affected the person with cancer. For example, infections were particularly concerning to some caregivers, and they worried about making the patient with cancer sick, thereby possibly causing a delay in treatment.

My dad came down with a cold. It’s very important that my mom doesn’t catch it, or it could prevent her from getting her last chemo treatment when she should.

Some caregivers wrote about how emotionally difficult it was to see the patient suffering, and how tiring caregiving could be.

It is routine for him to be up with her a few times in the middle of the night and he is extremely tired, both physically and emotionally, although you wouldn’t know it from talking to him.

Daily Living

Caregivers posted about life outside of cancer, including future plans or describing the patient’s day or their own. Some were able to go on vacation or simply enjoy time with their family at home.

She’s gotten out of the house several times and even has been cleaning the house.

We spent a week in Florida this past week, our yearly family vacation, the ride down and back was a little exhausting for mom but she did well, had a few rough days but had a fairly good week, even got on some bumper boats and played with everyone.

Caregivers wrote entire posts about a day in the life of the patient, describing the meals they ate, visitors they had, and different things they did during the day, such as running to the store or cleaning the house.

R.C. had an up and down day. She was feeling OK, so her mom, L.C., and S.P. talked her into a trip to Target. She popped a pain pill (just in case) and off they went. She got into the back seat and started getting car sick pretty quick. They made it to Target without a mishap in the back seat. Her excursion inside Target included riding in one of those electric powered carts. She said she had a few encounters with some buggies, but other than that it went well. She rode back home in the front seat this time, and when they got home, she got up and ate a good supper and felt good and was even laughing some from time to time.

P.T. also spent last night in the hospital with his dad. The nurses brought him ice cream and soda, which they both enjoyed, and they spent the night watching movies. Some great father–son time!

These descriptions tied closely with positive emotions, as the caregivers described the ability of the patient and family to savor/take joy in their day-to-day lives. Many expressed appreciation for being able to just run errands or clean around the house. They described having a normal day as a positive thing because cancer had changed their lives by preventing normal days. They cherished this sense of normalcy.

We had a nice, normal weekend and really got to enjoy being expectant parents.

This has been her first chance to be able to do normal things since all this started. She has been taking walks, gardening, and getting lots of sun.

Positive and Negative Emotions

Caregivers expressed much more positive than negative emotion in their writings. All cases exhibited positive writings from caregivers. The emotions shared were those of both patients and the caregivers themselves.

I spoke to her about an hour ago this morning and she sounded in very good spirits.

Things are looking up.

We all agreed to be cautiously optimistic.

Often caregivers expressed hope, kept a positive focus, and savored daily life events. They were hopeful that treatments would work and the patient’s symptoms would improve.

Mom has been seeing the infectious disease doctor every day this week to finish the antibiotic infusions for the blood infections. Hopefully, today is her last day.

When the fatigue starts going away hopefully his appetite will come back.

Caregivers wrote about how they and the patients were trying to make the most of the little things. They also shared when their child, grandchild, niece, or nephew were born.

Eight chemo treatments, 17 radiation treatments, 35 1/2 weeks of pregnancy, and a baby who arrived a month early and we made it—our mantra has become reality. Healthy T.S., healthy mom, and healthy baby.

This savoring and experiencing joy was evident in many of the cases.

Needless to say he is pretty excited to wear normal clothes again and to park the rolling IV stand that has followed him for the last couple of weeks. Word is P.T. was so excited when his IVs were removed that he broke out in a happy dance . . . to the concern of those around him that he may actually hurt himself! Must have been quite a scene.

Caregivers expressed gratitude for the support they received from their CaringBridge network, from formal caregivers (doctors, nurses, and dietitians), and from informal caregivers who helped them out in day-to-day life.

We are grateful and humbled by the many messages of encouragement, love, and support.

Everyone who has reached out, posted notes of support, delivered food, given hugs, shared their hearts, offered assistance with the kids or just stopped for a few minutes to offer up a prayer to our heavenly Lord it HAS HELPED!

It appeared at times that this positive focus was used to bolster others or themselves, although it may have been burdensome to the caregivers to maintain that appearance.

Although less common, caregivers expressed negative emotions, including feelings of anger, frustration, loss, and fear. Some shared how sad or overwhelmed they felt.

It’s so hard to see her not feeling good.

Obviously this wasn’t the news we were hoping for. My mom was counting on making it the 3 months then having a break so the news was very disappointing.

This news definitely has been really hard.

Anger, when shared, concerned the patient’s frustration or anger and not the caregivers’ own.

His defibrillator is doing its job, but is also seriously pissing R.C. off in the process. R.C. is not a happy camper today.

Young bubbly nurses with high squeaky voices don’t calm her nerves, nor do they make her comfortable and confident.

I know T.C. felt a bit of resentment the day before and morning of treatment—it’s hard to know that what you are about to do is definitely going to make you feel terrible.

Often, caregivers’ feelings of anxiety or feeling overwhelmed were shared at times of uncertainty, such as waiting for test results or procedures that would provide a clue to the patient’s next steps, or whether treatment was working.

Obviously we are very nervous about this appointment as it will be very uplifting to know we are on track treatment wise.

All this kind of makes us apprehensive in that what if the new chemo doesn’t work or lets the cancer get worse, and that opens the door for many other what ifs.

It is time again for L.T. to go in for a CT scan to check to see if there is any sign of cancer and to do a complete blood work up to see how everything is going with her recovery. The last scan was Nov. 12th (2 months post-op), this one, Tues., Feb 11th (today), will be 5 months post-op. It is weighing heavy on both of us.

In addition, when the patient died, caregivers shared their sadness. “We are so sad and miss her so much already.” Even at these times, however, they also focused on the positive, sharing how the patient was surrounded by family and friends and passed away peacefully.

I am heartbroken to have to tell you that a few hours after we brought R.C. home yesterday, he peacefully passed away. There are no words to describe the ache I have in my heart. However, I am comforted knowing he is no longer in any pain.

When negative thoughts or feelings were shared, they were almost always accompanied by positive feelings as well, compounding what appears to be a need to keep up a positive appearance on social media.

Spirituality

For the purpose of coding, the authors defined spirituality based on the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care’s definition (Pulchalski et al., 2009), which defines spirituality as the way people seek meaning and express meaning and how they feel connectedness to their surroundings, themselves, and others. Some caregivers expressed their spirituality and the spirituality of the patient in their writings. They wrote about reading or talking to spiritual leaders to help them deal with the uncertainty of the cancer diagnosis.

While these events have been taking place, my mom happened to stumble upon an archive of sermons while looking for some reading on Lent. These Biblical messages have been an answer to her constant prayers for God to show her Himself and our prayers for her to see the goodness and trustworthiness of God through all of this suffering.

The visiting pastor spoke directly to D.B. and S.B. about memories and family. He spoke of trials and struggles, and things that were about to happen that would become special.

Many shared inspirational or spiritual quotes that had helped them to deal with the cancer experience.

The enemy came to steal and destroy but that Jesus came that we might have life, and life more abundantly (John 10:10).

In 2 Timothy 4:7-8 the apostle Paul writes, “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Now there is in store for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge will award to me on that day. And not only for me, but also to all who have longed for his appearing.

In cases in which spirituality was expressed, it was one of the major themes throughout their writings and was primarily focused on a monotheistic religiosity with caregivers praising God often and even for the smallest improvements in the patient’s condition.

God has this!

We are so grateful for all of God’s amazing miracles.

Praise God your prayers were answered.

This was seen regardless of the patient’s illness trajectory.

Discussion

Although the focus was primarily on sharing information, through these disclosures caregivers often provided rich detail of how they were caring for the patient. They shared how they went with the patient to appointments or procedures and the questions they asked as caregivers. Caregivers did not often explicitly share their own feelings or burdens except in times of crisis or transition. When the patient was at key transition points, such as end of life or when waiting for the results of crucial tests, caregivers posted their worries and concerns. However, even at these times, they often tried to focus on the positive, and entries that had negative emotions often had positive hopeful messages as well. Research has shown that caregiver distress increases when these transitions occur (McGuire, Grant, & Park, 2012; Northouse, Katapodi, Schafenacker, & Weiss, 2012; Shaw et al., 2013). If caregivers are open about their feelings and burdens, this may help the social media network step up and offer more support at these critical times. However, if caregivers attempt to project the positive as well as negative during these times, this may send a mixed message to their guests. Guests may not recognize the caregivers’ needs. Twomey and O’Reilly (2017) performed a systematic review of studies examining Facebook and mental health/personality variables. The review explored studies that researched inauthentic versus authentic self-presentation. The studies found that those who do not share their true selves on social media often have low self-esteem and higher levels of social anxiety. Those who were more genuine in their presentation were more likely to report higher self-esteem and higher levels of perceived social support. It could be that those who have more social anxiety are less likely to be honest in what they are feeling because they fear others’ responses. Although these findings are specific to Facebook, they could reflect some of what drives the caregivers to share more or less on CaringBridge.

Although communicating with family and friends is often a caregiver role, social media simplifies this role by allowing the caregiver to communicate with multiple people at once; at the same time, the opportunity to provide real-time updates can make such communication burdensome. Apologies were seen often for delays in writing. They communicated about CaringBridge-related issues such as the site being down or accidentally posting an incomplete post. They explained their actions to the readers; for example, why they needed to limit visitors or why they had not posted recently. Many of the caregivers expressed the difficulty they had writing about the complexity of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and their disappointment at how the patient’s cancer treatment was going. One caregiver even struggled with how to explain to the patient why visitors came to his CaringBridge site but were not writing in the guestbook; caregivers and patients could see individuals were viewing the site even if guests were not posting. These examples demonstrate the additional burden communicating on these sites may cause.

This study identified additional caregiver experiences shared on social media: a focus on spirituality and daily life outside of the cancer diagnosis. The focus on spirituality has been shown to benefit patients and families as a source of hope and strength (Hamilton et al., 2017). The focus on daily life may reflect how patients and caregivers value quality of life. Both patients and caregivers desire a return to normalcy and old routines (Hamilton et al., 2017; Raque-Bogdan et al., 2015; SjÖvall, Gunnars, Olsson, & Thomé, 2011). Caregivers demonstrated these desires and values in their writings. In addition to these new findings, this research study reinforced the findings of current literature, which shows caregivers primarily use social media platforms for sharing patient health information (Anderson, 2011; Gage-Bouchard et al., 2017; Kim & Chung, 2007; Lu et al., 2017).

Limitations

Little research has focused on caregivers’ experiences on social media. Although this study focused on an emerging area of research, there were still limitations. Much of the analysis in this study relied on the coding of one individual. Confirmation bias was a risk to this research because the primary researcher conducted the initial coding independently. The focus of the research was on identifying caregivers’ experiences, so the primary researcher had to be cognizant of not over-interpreting meaning. The writing had to be explicit and not implied by the researchers. To diminish potential biases, the other authors provided review of decisions throughout the process. In addition, 10% of entries were coded by a second coder and an acceptable amount of agreement was identified. Despite careful attention, researcher biases may still exist, and it would be valuable to have other individuals examine the same cases to determine if similar findings resulted.

Because of the CaringBridge privacy agreement and no solicitation policy, the researchers were not able to contact the caregivers themselves or examine sites that had higher levels of privacy restrictions. These were major limitations of this study. Only what was disclosed on low-privacy sites could be examined. Individuals with higher privacy settings may have been more or less willing to share their emotions with their readers.

Another limitation was the use of cities for search terms. Because the CaringBridge search engine is intended to find individuals a user knows and not for identifying patients for research, cities were the most successful method for identifying patients; however, this limited the results to individuals residing in cities. Research on rural social media use indicates users prefer higher privacy settings and have fewer connections/relationships (Gilbert, Karahalios, & Sandvig, 2010). With these variations from urban social media users, they may also have differing disclosure patterns on websites such as CaringBridge.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses often recommend the use of social media sites to people with cancer and caregivers as a way for them to communicate with their family and friends. Many of these sites are adding additional tools to support patients with informational and tangible needs (Carezone, 2017; CaringBridge, 2014). Caregivers may need support in communicating the plan of care. Nurses educate caregivers during appointments or hospital admissions about the plan of care; answering questions and clarifying the plan for patients and caregivers can make it easier for them to communicate those plans to others. It is important to keep in mind the education nurses and other members of the healthcare team provide is often shared on these websites, so it is crucial to ensure the information provided is clear and correct.

The lack of disclosure of negative emotions on CaringBridge may mean caregivers need alternate resources to cope with their emotions and alternative routes to communicate them. Nurses in partnership with psychology providers can identify ways to promote honest self-disclosure and create trust and a comfortable environment for caregivers to express their burden and needs. Nurses can provide support for caregivers struggling with when and how often to communicate on the websites. They can reassure caregivers that communication should take place when it is the right time for them. If caregivers feel overwhelmed by the task of communicating, nurses can help them to identify resources and support to help them with the task of journaling. In addition, nurses can help caregivers identify secondary caregivers to update the site.

Implications for Research

Research specific to health communication on websites such as CaringBridge and to caregivers of adult patients with cancer is limited (Hamm et al., 2013; Kent et al., 2016). More research is needed to assess whether the variations seen in this study are replicable across different patient and family populations (Hamm et al., 2013). Future research should examine the other types of social media caregivers are using and follow up with the caregivers themselves to gain further insight into their experiences. Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter accounts may be places caregivers are more willing to talk about themselves because they are websites centered on the caregiver rather than CaringBridge, which is centered on the patient. Still much of what they write on these sites could continue to be focused on the patient. Facebook and Instagram are the most-used social media websites for adults (Pew Research Center, 2018). However, due to time constraints of caregiving, caregivers may not socialize or use their regular social media websites as often (NCI, 2019; Williams & Bakitas, 2012), and they may not use multiple social media platforms. In addition, with how difficult it may be for caregivers to share their emotions, anonymous applications may be a better avenue for understanding the caregiver experience. One such application, Whisper, allows individuals to write about whatever they want anonymously (Whisper, 2017). Caregivers may be more honest about their experiences because of the anonymity of the site. They may also connect with other caregivers with similar experiences without feeling judged by their in-person social network. Social media sites like CaringBridge bring together acquaintances as well as close family and friends. Caregivers may fear the impact of what they disclose to these groups because their words could follow them beyond CaringBridge.

Conclusion

This study provided valuable insights into what caregivers were willing to share with their CaringBridge network. Major categories identified included patient health information, cancer awareness and advocacy, social support, caregiver burden, daily living, emotions (positive and negative), and spirituality. In the cases examined, some caregivers shared negative emotions and reached out and requested support, whereas others did not. Understanding why certain caregivers do or do not share on social media can help nurses better support all caregivers.

About the Author(s)

Rosaleen D. Bloom, PhD, APRN, ACNS-BC, AOCNS®, is an assistant professor in the St. David’s School of Nursing at Texas State University in Round Rock; Susan Beck, PhD, APRN, FAAN, AOCN®, is professor emerita in the College of Nursing at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City; Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, PhD, MPH, is the program director of the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch of the Behavioral Research Program at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, MD; Maija Reblin, PhD, is an assistant member in the Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior at Moffit Cancer Center in Tampa, FL; and Lee Ellington, PhD, is a professor in the College of Nursing at the University of Utah. Bloom was supported by an American Cancer Society Doctoral Scholarship (DSCN-13-266-01-SCN). Beck has previously received honoraria from CareVive and has received support for travel from the International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care Board of Directors. All authors contributed to the conceptualization, design, and manuscript preparation. Bloom and Ellington completed the data collection and provided statistical support. Bloom, Beck, and Ellington provided the analysis. Bloom can be reached at r_b442@txstate.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2018. Accepted March 13, 2019.)

References

American Cancer Society. (2018). Cancer facts and figures, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and…

Anderson, I.K. (2011). The uses and gratifications of online care pages: A study of CaringBridge. Health Communication, 26, 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.558335

Bender, J.L., Jimenez-Marroquin, M., & Jadad, A.R. (2011). Seeking support on Facebook: A content of analysis of breast cancer groups. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13, e16. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1560

Bender, J.L., Wiljer, D., To, M.J., Bedard, P.L., Chung, P., Jewett, M.A., & Gospodarowicz, M. (2012). Testicular cancer survivors’ supportive care needs and use of online support: A cross-sectional survey. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 2737–2746.

Carezone. (2017). Carezone: Features. Retrieved from https://carezone.com/features

CaringBridge. (2014). CaringBridge offers more ways for people to connect and care during any health event. Retrieved from https://www.caringbridge.org/newsroom/news-releases/caringbridge-offers…

CaringBridge. (2018a). 2018 year in review. Retrieved from https://www.caringbridge.org/assets/ugc/content/2018_Annual_Report_v9_I…

CaringBridge. (2018b). Privacy policy. Retrieved from https://www.caringbridge.org/privacy-policy

DuBenske, L.L., Wen, K.Y., Gustafson, D.H., Guarnaccia, C.A., Cleary, J.F., Dinauer, S.K., & McTavish, F.M. (2008). Caregivers’ differing needs across key experiences of the advanced cancer disease trajectory. Palliative and Supportive Care, 6, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951508000400

Ellis, J. (2012). The impact of lung cancer on patients and carers. Chronic Respiratory Disease, 9, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972311433577

Family Caregiver Alliance. (2014). Emotional side of caregiving. Retrieved from https://www.caregiver.org/emotional-side-caregiving

Gage-Bouchard, E.A., LaValley, S., Mollica, M., & Beaupin, L.K. (2017). Cancer communication on social media: Examining how cancer caregivers use Facebook for cancer-related communication. Cancer Nursing, 40, 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000418

Gilbert, E., Karahalios, K., & Sandvig, C. (2010). The network in the garden: Designing social media for rural life. American Behavioral Scientist, 53, 1367–1388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210361690

Given, B.A., Given, C.W., & Sherwood, P.R. (2012). Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. Journal of Supportive Oncology, 10, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2011.10.003

Gofton, T.E., Graber, J., & Carver, A. (2012). Identifying the palliative care needs of patients living with cerebral tumors and metastases: A retrospective analysis. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 108, 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-012-0855-y

Hamilton, J.B., Worthy, V.C., Moore, A.D., Best, N.C., Stewart, J.M., & Song, M.K. (2017). Messages of hope: Helping family members to overcome fears and fatalistic attitudes toward cancer. Journal of Cancer Education, 32, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-015-0895-z

Hamm, M.P., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Scott, S.D., Given, L.M., & Hartling, L. (2013). Social media use among patients and caregivers: A scoping review. BMJ Open, 3, e002819. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002819

Holman, A. (2017). Content analysis, process of. In M. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 245–248). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hsieh, H.F., & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jacobs, B.J. (2017). Repeat after me: I am a good caregiver. Retrieved from https://www.aarp.org/home-family/caregiving/info-2017/tips-for-caregive…

Kent, E.E., Rowland, J.H., Northouse, L., Litzelman, K., Chou, W.Y., Shelburne, N., . . . Huss, K. (2016). Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer, 122, 1987–1995.

Kim, S., & Chung, D.S., (2007). Characteristics of cancer blog users. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 95, 445–450. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.95.4.445

Lambert, S., Girgis, A., Lecathelinais, C., & Stacey, F. (2013). Walking a mile in their shoes: Anxiety and depression among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors at 6 and 12 months post-diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1495-7

Lapid, M.I., Atherton, P.J., Clark, M.M. Kung, S., Sloan, J.A., & Rummans, T.A. (2015). Cancer caregiver: Perceived benefits of technology. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 21, 893–902. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0117

Lepore, S.J., & Revenson, T.A. (2007). Social constraints on disclosure and adjustment to cancer. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00013.x

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C.C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research, 28, 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x

Lu, Y., Wu, Y., Liu, J., Li, J., & Zhang, P. (2017). Understanding health care social media use from different stakeholder perspectives: A content analysis of an online health community. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e109. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7087

McGuire, D.B., Grant, M., & Park, J. (2012). Palliative care and end of life: The caregiver. Nursing Outlook, 60, 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2012.08.003

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Cancer Institute. (2014). Caring for the caregiver. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/caring-for-the-ca…

National Cancer Institute. (2019). Family caregivers in cancer: Roles and challenges (PDQ®). Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/family-friends/family-caregi…

Northouse, L.L., Katapodi, M.C., Schafenacker, A.M., & Weiss, D. (2012). The impact of caregiving on the psychosocial well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 28, 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.006

Pew Research Center. (2013). How online family caregivers interact with their health online. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2013/06/20/how-online-family-caregivers-int…

Pew Research Center. (2018). Social media fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

Prestin, A., Vieux, S.N., & Chou, W.Y. (2015). Is online health activity alive and well or flatlining? Findings from 10 years of the Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 790–798. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018590

Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., . . . Sulmasy, D. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12, 885–904. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0142

Raque-Bogdan, T.L., Hoffman, M.A., Ginter, A.C., Piontkowski, S., Schexnayder, K., & White, R. (2015). The work life and career development of young breast cancer survivors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000068

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Saria, M.G., Courchesne, N.S., Evangelista, L., Carter, J.L., MacManus, D.A., Gorman, M.K., . . . Maliski, S.L. (2017). Anxiety and depression associated with burden in caregivers of patients with brain metastases. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.ONF.306-315

Shaw, J., Harrison, J., Young, J., Butow, P., Sandroussi, C., Martin, D., & Solomon, M. (2013). Coping with newly diagnosed upper gastrointestinal cancer: A longitudinal qualitative study of family caregivers’ role perception and supportive care needs. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1575-8

U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Census 2000 gateway. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1998). Informal caregiving: Compassion in action. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/informal-caregiving-compassion-action

van Ryn, M., Sanders, S., Kahn, K., van Houtven, C., Griffin, J.M., Martin, M., . . . Rowland, J. (2011). Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: A hidden quality issue? Psycho-Oncology, 20, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1703

Wang, Y.C., Kraut, R.E., & Levine, J.M. (2015). Eliciting and receiving online support: Using computer-aided content analysis to examine the dynamics of online social support. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e99. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3558

Whisper. (2017). Community guidelines. Retrieved from http://whisper.sh/guidelines

Williams, A.L., & Bakitas, M. (2012). Cancer family caregivers: A new direction for interventions. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15, 775–783. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0046

Word, D.L., Coleman, C.D., Nunziata, R., & Kominski, R. (n.d.). Demographic aspects of surnames from Census 2000. Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/topics/genealogy/2000surnames/surnames.pdf