The Relationship Between Colorectal Cancer Survivors’ Positive Psychology, Symptom Characteristics, and Prior Trauma During Acute Cancer Survivorship

Objectives: To examine colorectal cancer survivors’ positive psychology and symptom characteristics, and to assess for potential impact of prior trauma on these relationships during acute cancer survivorship.

Sample & Setting: A cross-sectional study of 117 colorectal cancer survivors was conducted at a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center.

Methods & Variables: Participants completed a demographic questionnaire, and the Carver Benefit Finding Scale and Posttraumatic Growth Inventory assessed positive psychology. Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression analyses were performed.

Results: 49 symptoms were reported and varied based on prior trauma. Significance was found between positive psychology and symptom frequency (p < 0.001); symptoms reported almost daily and daily were inversely related to positive psychology.

Implications for Nursing: Nurses should prioritize symptoms; less frequent symptoms improve positive psychology. Early identification of positive changes may promote survivors’ self-awareness and management skills to mitigate adverse symptoms.

Jump to a section

Colorectal cancer (CRC), a cancer of the digestive tract, colon, or rectum, is the fourth most common cancer (about 1.9 million cases per year) and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally (American Cancer Society, 2021; National Cancer Institute, 2021; Siegel et al., 2019). Data show that CRC cases are increasing, particularly among individuals aged 20–50 years (American Cancer Society, 2020). However, advances in detection and treatment have prolonged survival, and survivors are living well beyond 20 years postdiagnosis. Mortality rates have subsequently decreased by 2.3% since 2012 (Howlader et al., 2019; Siegel et al., 2019). Factors that improve adverse outcomes (e.g., symptoms) have become increasingly more important throughout the cancer survivorship continuum, which is the length of time from a cancer diagnosis until the end of life (Mullan, 1985; Sheikh-Wu et al., 2021, 2022). Studies show that cancer survivors report beneficial and adverse experiences associated with a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatments. For example, survivors report positive changes associated with receiving a cancer diagnosis, such as increased quality of life and enhanced life satisfaction (Carver & Antoni, 2004; Wang et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2017). In addition to survivors’ positive changes, survivors also report adverse symptoms, physical or psychological subjective signs that indicate an abnormal condition within the human body, typically caused by an injury or disease, and measured by occurrence, frequency, and severity (Gapstur, 2007; Sheikh-Wu et al., 2020, 2021; Sreedhar, 2021; Stark et al., 2012). Adverse symptoms tend to accumulate from cancer and its treatments.

Positive psychology, which includes benefit finding and post-traumatic growth, is a potential change associated with a cancer diagnosis and can affect outcomes. Positive psychology focuses on an individual’s traits or character strengths, positive mental states, and social organizations that can improve outcomes (Casellas-Grau et al., 2016; Cerezo et al., 2014; Macaskill, 2016). Benefit finding is a process where a survivor reassigns positive meaning and values to their cancer diagnosis based on the benefits they identify with and that begins immediately after a person is diagnosed with cancer (Andrykowski et al., 2017; Jansen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015). Post-traumatic growth is one’s ability to cope after a traumatic event (Batista et al., 2014; Jansen et al., 2011; Occhipinti et al., 2015; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Post-traumatic growth is a slow, progressive change in interpersonal and life perspective that occurs through conscious cognitive coping (Batista et al., 2014; Jansen et al., 2011; Occhipinti et al., 2015; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Studies show that a traumatic event may lead to changes in benefit finding and post-traumatic growth. A traumatic event is considered an unexpected and uncontrolled crisis, such as a physical or sexual assault or abuse, sudden death of a loved one, natural disaster, or severe illness or hospitalization that produces lifelong effects (Menger et al., 2020; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Individuals experiencing a traumatic event may evaluate, assign, and cope with the event in such a way that they obtain a sense of benefit from the trauma (Casellas-Grau et al., 2016; Menger et al., 2020), thereby leading to higher levels of benefit finding and post-traumatic growth. This change in positive psychology can influence one’s perspective of subsequent traumas, as could be the case with someone who has prior trauma and then develops a new trauma, like a diagnosis of CRC.

Positive psychology influences the perception of living by providing an optimistic outlook to one’s life and may also affect how CRC survivors view their symptoms. For example, a survivor with high levels of positive psychology may view their symptoms more favorably than a survivor with low levels of positive psychology. Studies among breast and mixed cancer populations have shown that survivors with high levels of benefit finding and post-traumatic growth report fewer psychological distress symptoms (stress, anxiety, and depression) and fewer adverse outcomes (Antoine et al., 2018; Hendriks & Aabidien, 2020; Llewellyn et al., 2013; McNulty & Fincham, 2012; Walsh et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). Differences in benefit finding and post-traumatic growth levels may affect symptoms among CRC survivors during acute cancer survivorship, which is the length of time from cancer diagnosis to the completion of primary treatment (Mullan, 1985; Sheikh-Wu et al., in press, 2022); however, evidence is sparse.

CRC survivors experience a wide range of symptoms, including depression, body image disorder, sexual dysfunction, bowel changes (e.g., constipation; excessive amounts of gas; narrow, ribbon-like stool), and neuropathy of the hands and feet (Deshields et al., 2014; Juul et al., 2018; Miaskowski et al., 2017; Mosher & Duhamel, 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2015; Sheikh-Wu et al., 2022). Symptoms are more abundant and severe and accumulate during acute cancer survivorship because survivors begin to undergo cancer treatment after diagnosis (Sheikh-Wu et al., in press, 2022). CRC survivors, much like breast, prostate, or lung cancer survivors, would undoubtedly have additional adverse outcomes if their symptoms were not managed (Sheikh-Wu et al., 2021, 2022). However, few studies have examined the effect of positive psychology and symptoms characteristics (i.e., occurrence, frequency, and severity) among CRC survivors during acute cancer survivorship.

Little is known about the effects of positive psychology and symptom characteristics such as occurrence, frequency, and severity, particularly during acute cancer survivorship among an under-researched CRC population (Andrykowski et al., 2017; Carver & Antoni, 2004; Lee et al., 2017; Seo & Kwon, 2018; Wen et al., 2017). In addition, understanding of the effects of prior trauma within the context of positive psychology and symptoms during acute cancer survivorship is limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine levels of positive psychology (benefit finding and post-traumatic growth), symptom characteristics (occurrence, frequency, and severity), and differences between CRC survivors with and without a prior traumatic event during acute cancer survivorship.

Methods

Study Design, Sample, and Framework

From the literature, a study framework was developed to guide the research questions, and it was used to describe the relationships between symptom characteristics and positive psychology (i.e., the aggregate of benefit finding and post-traumatic growth) among CRC survivors with or without a prior traumatic event during acute cancer survivorship. A cross-sectional study of 117 CRC survivors was conducted at a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center in South Florida. Recruitment and data collection occurred from April to August 2021. The institutional review board at the University of Miami approved the study. Electronic informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waivers were obtained prior to data collection.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) being aged at least 18 years; (b) having the ability to comprehend English; (c) having a diagnosis of colon, rectal, or CRC; and (d) undergoing active treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) having a diagnosis of severe mental illness (e.g., active bipolar disorder, schizophrenia); (b) having completed cancer treatment or being documented as terminally ill, or initiating hospice, comfort care, or end-of-life measures; and (c) being unable or unwilling to give informed consent.

Outcome Instruments

Instruments with established scoring procedures and evidence of validity with mixed cancer survivors were used in this study. All self-report measures were completed in REDCap (Harris et al., 2019). The authors created a 25-item self-report questionnaire to assess participant demographic information. The questionnaire included age, marital status, education level, and cancer-related questions. Traumatic events prior to survivors’ cancer diagnosis were assessed by asking a multiple-part question. Questions addressed if the participant had ever experienced a traumatic event prior to their cancer diagnosis and how long ago the traumatic event took place. In addition, if the participant wanted to elaborate on the type of traumatic event, an open-ended comment box was available. Traumatic events were defined as a distressing incident that causes physical, psychological, emotional, or spiritual harm that involves an actual or perceived threat to a person (Menger et al., 2020; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996).

A modified Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist (Williams et al., 2013, 2015) of 49 items was used to assess the participants’ weekly symptom occurrence, frequency (how often the symptom occurred: randomly [1–3 times], weekly [4–6 times], almost daily [7–9 times], or daily [10 or more times]), and severity (mild, moderate, severe, or very severe). The original checklist has shown good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.8 in samples of mixed cancer survivors (Mansouri et al., 2017; Sreedhar, 2021; Williams et al., 2013, 2015). The Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist was modified to include additional symptoms (n = 24) common among CRC survivors (e.g., mucus in the stool, feeling pressure in gastrointestinal tract, anal pain). In addition, the Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist assessed psychological distress symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression.

Positive psychology was assessed by the Carver Benefit Finding Scale and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. The Carver Benefit Finding Scale assessed survivors’ benefit finding level using a 17-item questionnaire (Antoni et al., 2001; Carver, 2012; Carver & Antoni, 2004). The items are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The Carver Benefit Finding Scale has shown good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 from a sample size of 209 men with prostate cancer (Pascoe & Edvardsson, 2015) and 0.87 in a Chinese population with CRC (Chen et al., 2021). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) is a 21-item questionnaire assessing survivors’ positive outcomes after a traumatic event, such as cancer. The inventory items are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (did not experience) to 5 (very great degree) and has shown good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.87 to 0.97 in samples of mixed cancer survivors and the general population (n = 85 and 604, respectively) (Grad & Zeligman, 2017; Park & Sinnott, 2018; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; Zhang et al., 2019). A combined score of the Carver Benefit Finding Scale and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory calculated the total positive psychology score (Jansen et al., 2011).

Statistical Methods

G*Power, version 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009), was used to estimate the post-hoc power and sample size for the research study. A power of 0.99 was achieved with 117 participants for a bivariate model with an effect size of 0.2 and alpha = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Measures of central tendencies and percentages were obtained to determine the study sample demographics, symptom characteristics, benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, positive psychology, and history of prior trauma. Covariates of age, sex, cancer stage, and treatment type were adjusted for symptom occurrence. For between-group differences in benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology based on sex and prior trauma, the Mann–Whitney U test (Hart, 2001) was performed. For between-group differences in post-traumatic growth, benefit finding, and positive psychology based on age, education, and postdiagnosis months, the Kruskal–Wallis H test (Ostertagová et al., 2014) was performed. Nonparametric statistical tests were used to test noncontinuous data. Multiple linear regression (Grégoire, 2014) was used to model the relationship between positive psychology and (a) having undergone a prior traumatic event; (b) symptom number, frequency, and severity; and (c) psychological distress symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. The four assumptions of multiple linear regression (normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and independence) were tested and met (Garson, 2014; Osbourne & Waters, 2002).

Results

Demographic and Sample Characteristics

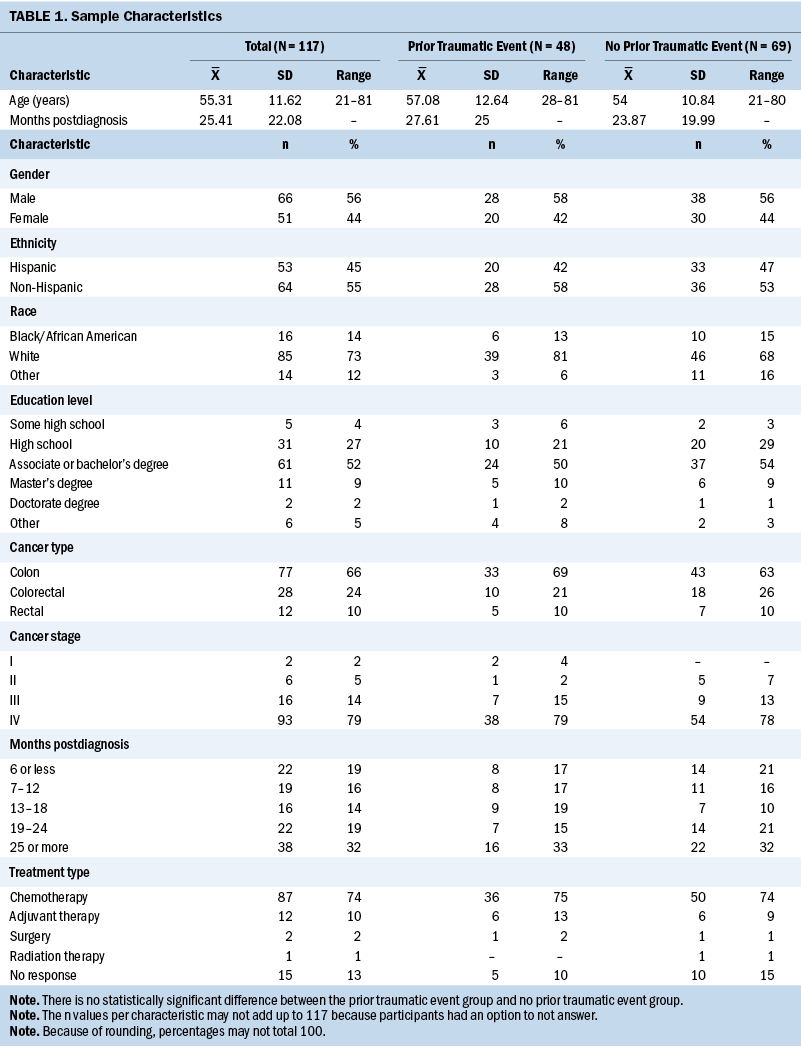

A total of 117 survivors completed the study. Seventy-seven had colon cancer, 12 had rectal cancer, and 28 had CRC, with cancer stages ranging from I to IV. Participants’ mean age was 55.31 years, and 44% were female. Forty-one percent of survivors reported a traumatic event prior to cancer. See Table 1 for aggregate sample and group (prior trauma and no prior trauma) demographics and health-related characteristics. There were no differences in demographics or health-related characteristics between CRC survivors with and without prior trauma. All participants were actively undergoing treatment.

Symptom Characteristics

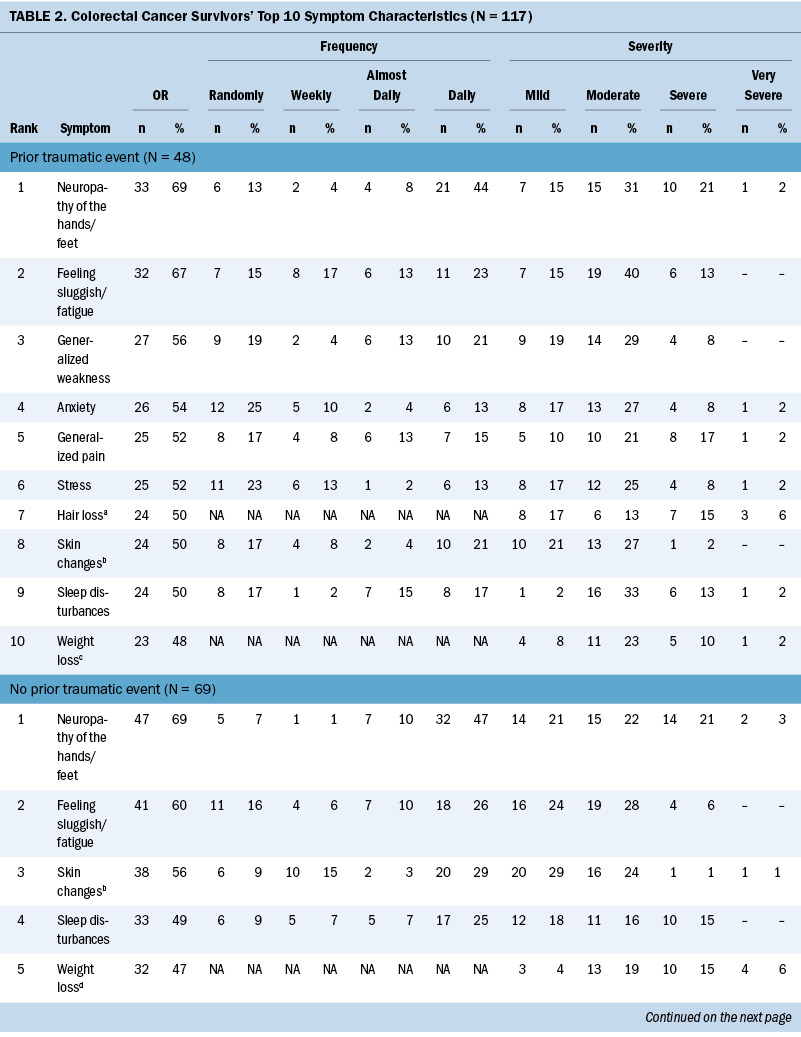

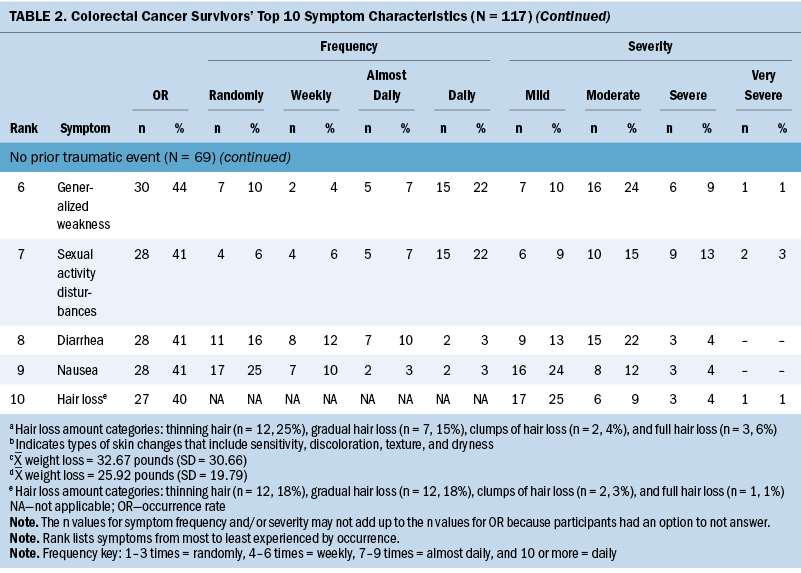

The Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist assessed 49 symptoms based on occurrence, frequency, and severity. Table 2 details the top 10 symptoms reported among survivors based on history of prior trauma. Symptom data are rank ordered based on occurrence; symptom frequency and severity are also reported. After adjusting for age, sex, cancer stage, and treatment type for symptom occurrence, the authors observed the following:

- Age was not found to be significant (p > 0.05).

- Sex was significant for symptoms of hair loss (women reported a higher occurrence rate [p = 0.003]) and abdominal bloating (men reported a higher occurrence rate [p = 0.042]).

- Cancer stage was significant for symptoms of sore veins (p = 0.012) and gastrointestinal pressure (p = 0.019) (survivors with stage III cancer reported a higher occurrence rate).

- Treatment type was significant for symptoms of difficulty swallowing, dizziness/lightheadedness, headache, and anal pain (survivors undergoing chemotherapy reported a higher occurrence rate) (p < 0.001).

The most common symptoms among survivors with a prior traumatic event were neuropathy of the hands/feet, feeling sluggish/fatigue, generalized weakness, anxiety, and generalized pain. The most common symptoms reported among survivors without a prior traumatic event were neuropathy of the hands/feet, feeling sluggish/fatigue, skin changes (sensitivity, discoloration, texture, and dryness), sleep disturbances, and weight loss. Psychological distress symptoms varied between those with and without prior trauma. Survivors with a prior traumatic event reported a higher occurrence of anxiety (54% versus 31%, p = 0.011), stress (52% versus 38%, p = 0.159), and depression (40% versus 22%, p = 0.047), compared to survivors without a prior traumatic event. All three psychological distress symptoms were reported in 49% of the survivors with prior trauma, compared to 30% in those without prior trauma.

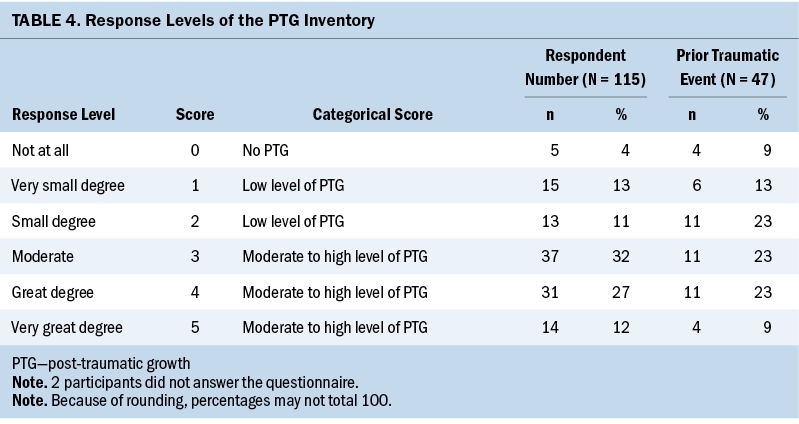

Positive Psychology, Benefit Finding, and Post-Traumatic Growth Characteristics

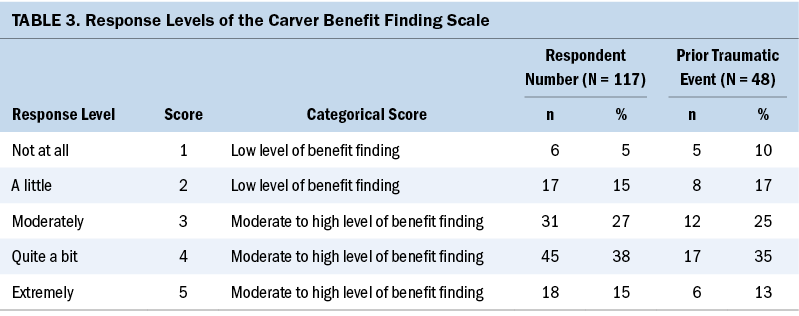

Nearly all survivors (about 90%) reported some level of benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology (see Tables 3 and 4). More than half of the survivors reported moderate to high levels of benefit finding (80%, mean = 3.42, SD = 1.05), post-traumatic growth (71%, mean = 3.01, SD = 1.27), and positive psychology (75%, mean = 3.21, SD = 1.08). Forty-one percent of the survivors reported a prior traumatic event before their CRC diagnosis (benefit finding: mean = 3.3, SD = 1.12, post-traumatic growth: mean = 2.67, SD = 1.41, and positive psychology: mean = 2.98, SD = 1.2). CRC survivors with a prior traumatic event reported lower post-traumatic growth levels (t[–2.419] = –0.572, p = 0.017). No statistically significant relationship was found between prior trauma with benefit finding (t[–1.063] = –0.209, p = 0.29) or positive psychology levels (t[–1.93] = –0.081, p = 0.056).

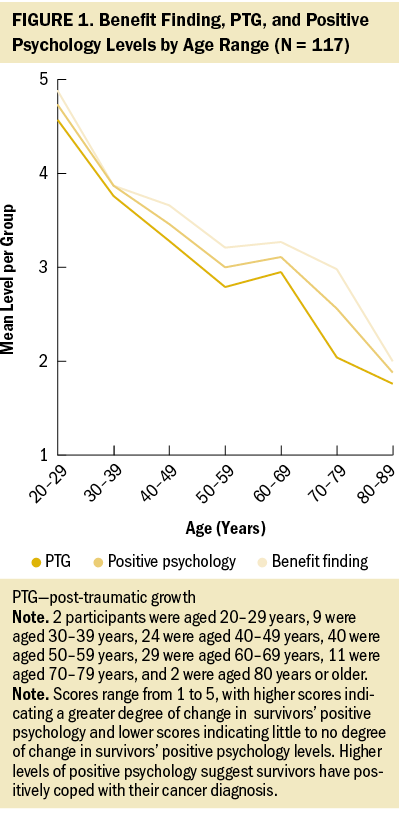

Group Difference and Positive Psychology Characteristics

The authors assessed differences among age, sex, education, and postdiagnosis months between CRC survivors’ (n = 117) benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels. There were only differences with age and benefit finding (p = 0.01), post-traumatic growth (p = 0.007), and positive psychology levels (p = 0.012) (see Figure 1). Positive psychology levels decreased with increasing age. CRC survivors aged 20–29 years reported the highest levels of benefit finding (mean = 4.88), post-traumatic growth (mean = 4.57), and positive psychology (mean = 4.73), and those aged 80–89 years reported the lowest levels of benefit finding (mean = 2), post-traumatic growth (mean = 1.76), and positive psychology (mean = 1.88).

The authors evaluated the effect of prior trauma and group differences on benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels. They observed a relationship between sex and post-traumatic growth levels (p = 0.023) among CRC survivors with a prior traumatic event. The mean post-traumatic growth level was 3.09 for men and 2.1 for women. Among CRC survivors without a prior traumatic event, the authors observed significant relationships between sex and (a) benefit finding levels (p = 0.031, meanmale score = 3.79 and meanfemale score = 3.24); (b) post-traumatic growth levels (p = 0.023, meanmale score = 3.63 and meanfemale score = 2.91); and (c) positive psychology levels (p = 0.015, meanmale score = 3.7 and meanfemale score = 3.07). There was no meaningful relationship with education, postdiagnosis months, and age.

Relationships Between Positive Psychology Levels and Symptoms

The authors assessed the relationship between positive psychology and symptom characteristics (number, frequency, and severity) and psychological distress symptoms (stress, anxiety, and depression). Only positive psychology and symptom frequency (F[3,112] = 6.151, p < 0.001) were significant. Symptoms that occurred at random were significantly related to increased positive psychology levels (t[13.26] = 3.914, p < 0.001). Symptoms that occurred almost daily (t[–3.2] = –1.09, p = 0.002) and daily (t[2.7] = –0.92, p = 0.008) significantly decreased positive psychology levels among CRC survivors. Symptoms that occurred weekly were not significantly related to positive psychology levels.

The authors examined group differences in positive psychology levels and symptom characteristics (number, frequency, and severity) and psychological distress symptoms (stress, anxiety, and depression) among CRC survivors with and without a prior traumatic event. There were no significant findings among CRC survivors with a prior traumatic event. The authors only observed a relationship between positive psychology and symptom frequency (F[1,64] = 8.129, p = 0.006) among CRC survivors without a prior traumatic event. Symptoms that occurred daily significantly decreased positive psychology levels (t[2.673] = 1.052, p = 0.01). Symptoms that occurred randomly, weekly, and almost daily were not significantly related to positive psychology levels among survivors without a prior traumatic event.

Discussion

This study has several observations that warrant additional discussion. This study is one of few studies to assess the relationships between positive psychology (benefit finding and post-traumatic growth) and symptom characteristics (occurrence, frequency, and severity) among CRC survivors during acute cancer survivorship. Prior trauma has been associated with changes in positive psychology, and the authors assessed for the potential impact of prior trauma on these relationships.

First, the current study observed a significant relationship between positive psychology levels and symptom frequency among CRC survivors. Symptoms reported almost daily and daily were inversely related to positive psychology levels during acute cancer survivorship. This finding suggests that the more frequent the symptom occurrence, the more impact the symptom has on the survivor, such as blunting or reducing any potential short- or long-term psychological growth from coping and dealing with a CRC diagnosis. Also, longitudinal studies are warranted to determine if this relationship is sustained after acute cancer survivorship because studies report fewer symptoms after the acute phase. Studies show there are benefits of higher levels of positive psychology, including increased levels of well-being and quality of life (e.g., life satisfaction and purpose) and reduced morbidity (e.g., improvement in physical and psychological function) (Andrykowski et al., 2017; Casellas-Grau et al., 2016; Cerezo et al., 2014; Macaskill, 2016; Menger et al., 2020). This suggests that reducing symptom frequency or potentially managing symptoms early could increase positive psychology levels, resulting in greater life satisfaction and improved health-related outcomes.

Second, higher levels of positive psychology have been associated with a reduced burden of psychological distress symptoms (stress, anxiety, and depression) across several cancer populations (Andrykowski et al., 2017; Hendriks et al., 2020; Mosher & Duhamel, 2012; Wang et al., 2015). However, the current study did not observe a relationship between benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, or positive psychology levels, and psychological distress symptoms among the study aggregate. However, when the authors evaluated the relationship between positive psychology and psychological distress symptoms based on the history of a reported prior traumatic event, CRC survivors with a prior traumatic event reported more psychological distress symptoms. Individuals with a history of prior trauma have been shown to have higher occurrence rates of psychological distress symptoms than those without a prior trauma in various populations (Kessler et al., 2018). Specifically, studies have shown that those with prior trauma who experience a new and similar trauma (e.g., previously unexpected loss of a partner, then a new CRC diagnosis) are more likely to report high levels of psychological distress independent of positive psychology levels (Fang et al., 2020; Slanbekova et al., 2017). The high levels of psychological distress seen in this type of circumstance may represent a post-traumatic stress disorder and may blunt any potential benefit from post-traumatic growth or benefit finding affecting levels of positive psychology (Fang et al., 2020; Slanbekova et al., 2017). Although there was no statistically significant relationship between levels of positive psychology and psychological distress symptoms, this does not exclude a potentially clinically meaningful effect. For example, studies should evaluate if positive changes associated with cancer affected health-seeking behaviors, such as self-management of symptoms, which could influence the quality of life and reduce morbidity.

Third, understanding of benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels among CRC survivors throughout acute cancer survivorship is limited. More than 70% of the current sample had moderate to high benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels, suggesting that CRC survivors positively cope with their cancer during acute cancer survivorship. In addition, CRC survivors without a history of prior trauma reported more positive changes (e.g., higher levels of benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology) associated with their cancer diagnosis. The authors observed differences in positive changes based on prior trauma and sex. Among CRC survivors with prior trauma, men reported higher benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels than women, suggesting that men may adapt and cope faster when faced with a traumatic event. The current CRC survivor sample was predominantly male (56%) and is reflective of national trends. However, studies regarding benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology have been conducted predominantly with breast cancer survivors (Antoine et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2020), limiting knowledge of the effects in men. Studies conducted with prostate cancer survivors have shown low to moderate levels of positive psychology (Pascoe & Edvardsson, 2015; Thornton & Perez, 2006). However, these studies have been conducted with older adult prostate cancer survivors (aged 65 years or older) post–cancer treatment (Pascoe & Edvardsson, 2015; Thornton & Perez, 2006) and did not account for prior history of trauma. Similar findings are reported among veteran, post-traumatic stress disorder, and sexual assault populations regarding moderate positive psychology levels and psychological distress symptoms following exposure to traumatic events (Tsai et al., 2015; Ulloa et al., 2016). However, findings are still inconsistent, which may be because of the variability of study design, time since the traumatic event exposure, theoretical framework, and measurement tool.

From the aggregate sample, the authors observed that benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology levels decreased with advancing age during acute cancer survivorship. This observation is independent of a history of prior trauma. Young CRC survivors reported higher positive changes related to their cancer. Previous work has suggested that positive psychology levels remain consistent regardless of age because the cognitive coping process is based on one’s personality characteristics and traits (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). However, research in various cancer populations has indicated an inverse relationship between post-traumatic growth and age (Koutrouli et al., 2016). That is, younger survivors may perceive an unexpected cancer diagnosis as more traumatic or life-threatening compared to older survivors. Therefore, younger survivors may develop higher levels of positive psychology (post-traumatic growth and benefit finding) because their perception of the CRC diagnosis (e.g., trauma) was significantly greater.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Because this is a cross-sectional study, data were obtained from one point in time, making it difficult to assess positive psychology and symptom trajectories. However, the authors minimized this concern by sampling CRC survivors across the acute cancer survivorship continuum. Future work should be prospective in nature with repeated measures to quantify positive psychology levels and evaluate their effects on symptom trajectories among CRC survivors. In addition, a larger sample size (e.g., equal numbers per age group with and without prior trauma) would allow for a better understanding of relationships among age, sex, prior trauma, symptoms, and positive psychology levels among CRC survivors. Given the predominance of stage IV CRC survivors in the current sample, it is also difficult to determine the relationship between positive psychology and cancer stage, and benefits of positive psychology reported may reflect effects from age and other factors. The current sample was reflective of national CRC demographic characteristics regarding age, sex, cancer stage, and education levels; however, the study underrepresented non-Hispanic Black individuals, limiting generalizability despite being reflective of South Florida demographics.

Implications for Nursing

Oncology nurses are well poised to implement and promote self-management skills to reduce adverse outcomes, like symptoms among CRC survivors. Nurses need to prioritize and track symptom frequency; less frequent symptoms improve positive psychology levels (positive change related to cancer) among CRC survivors. Most importantly, nurses need to be educated on positive psychology and the associated benefits that improve survivors’ outcomes (e.g., quality of life, life satisfaction) and reduce negative symptom burden during acute cancer survivorship. A better understanding of CRC survivors’ positive psychology may help improve survivors’ awareness of these changes associated with benefit finding and post-traumatic growth and reduce adverse symptoms throughout their treatment.

Additional emphasis needs to be placed on positive psychology in the clinical setting to aid nurses’ understanding of positive changes associated with survivors’ cancer and help identify potential survivors who are not adjusting to their cancer during treatment. Nurses should assess for prior trauma to identify any potential impacts prior trauma may have on the survivor, their symptoms, and positive adjustment to their cancer during acute cancer survivorship. Early identification of positive changes from the survivors and healthcare team (i.e., nurse practitioners and nurses) may promote the survivors’ self-awareness and management skills, mitigating the adverse symptoms of treatments during acute cancer survivorship. Therefore, understanding the role of positive psychology on the symptom characteristics may help identify CRC survivors’ risk factors and potential modifiable factors that could be manipulated to develop interventions.

Conclusion

This study evaluated CRC survivors’ positive psychology (benefit finding and post-traumatic growth); symptom characteristics (occurrence, frequency, and severity); and differences between survivors with and without a prior traumatic event during acute cancer survivorship. This study is one of the first to gather new insights regarding CRC survivors’ positive psychology and symptoms during treatment. Forty-one percent of CRC survivors had a history of a prior traumatic event, and symptoms varied based on survivors with a prior traumatic event. CRC survivors’ positive psychology levels declined with age, and men reported higher levels of benefit finding, post-traumatic growth, and positive psychology. Understanding the importance of relationships between positive psychology, symptoms, and health outcomes is important for nurses because nurses are poised to evaluate and monitor for changes in positive psychology and symptoms during acute cancer survivorship. A better understanding of these relationships can provide the foundation for interventions that increase positive psychology and improve symptom management among CRC survivors across cancer survivorship.

About the Authors

Sameena F. Sheikh-Wu, PhD, BA, BSN, RN-BC, is a PhD student, Debbie Anglade, PhD, RN, MSN, CPHQ, CCM, is an associate professor of clinical nursing, and Karina A. Gattamorta, PhD, is a research associate professor, all in the School of Nursing and Health Studies at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, FL; Canhua Xiao, PhD, RN, FAAN, is an associate professor in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University in Atlanta, GA; and Charles A. Downs, PhD, ACNP-BC, FAAN, is an associate professor in the School of Nursing and Health Studies at the University of Miami. This research was supported, in part, by a dissertation grant from the Beta Tau Chapter of Sigma. Sheikh-Wu completed the data collection. Sheikh-Wu and Gattamorta provided statistical support. Sheikh-Wu and Xiao provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design and the manuscript preparation. Sheikh-Wu can be reached at sfs23@miami.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted March 2022. Accepted June 17, 2022.)

References

American Cancer Society. (2020). Colorectal cancer rates rise in younger adults. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/colorectal-cancer-rates-rise-in-youn…

American Cancer Society. (2021). Survival rates for colorectal cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-s…

Andrykowski, M.A., Steffens, R.F., Bush, H.M., & Tucker, T.C. (2017). Posttraumatic growth and benefit-finding in lung cancer survivors: The benefit of rural residence? Journal of Health Psychology, 22(7), 896–905. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315617820

Antoine, P., Dauvier, B., Andreotti, E., & Congard, A. (2018). Individual differences in the effects of a positive psychology intervention: Applied psychology. Personality and Individual Differences, 122(1), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.024

Antoni, M.H., Lehman, J.M., Kilbourn, K.M., Boyers, A.E., Culver, J.L., Alferi, S.M., . . . Carver, C.S. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology, 20(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20

Batista, S., Charro, S., Ribeiro, A., & Monteiro, L. (2014). Posttraumatic growth in oncology. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 375–375.

Carver, C.S. (2012). Finding benefit in the experience of breast cancer: Issues and questions. International Journal of Psychology, 47, 100.

Carver, C.S., & Antoni, M.H. (2004). Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychology, 23(6), 595–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.595

Casellas-Grau, A., Font, A., Vines, J., & Ochoa, C. (2016). Positive psychology functioning in breast cancer: An integrative review. Breast, 27, 136–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.04.001

Cerezo, M.V., Ortiz-Tallo, M., Cardenal, V., & de La Torre-Luque, A. (2014). Positive psychology group intervention for breast cancer patients: A randomised trial. Psychological Reports, 115(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.2466/15.20.PR0.115c17z7

Chen, M., Gong, J., Li, J., Luo, X., & Li, Q. (2021). The experienced benefits of the 17-item Benefit Finding Scale in Chinese colorectal cancer survivor and spousal caregiver couples. Healthcare, 9(8), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9050512

Deshields, T., Potter, P., Olsen, S., & Liu, J. (2014). The persistence of symptom burden: Symptom experience and quality of life of cancer patients across one year. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(4), 1089–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-2049-3

Fang, S., Chung, M.C., & Wang, Y. (2020). The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 992.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Gapstur, R.L. (2007). Symptom burden: A concept analysis and implications for oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(3), 673–680. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.ONF.673-680

Garson, G.D. (2014). Multiple regression. Statistical Associates Publishers. http://www.statisticalassociates.com/booklist.htm

Grad, R.I., & Zeligman, M. (2017). Predictors of post-traumatic growth: The role of social interest and meaning in life. Journal of Individual Psychology, 73(3), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2017.0016

Grégoire, G. (2014). Multiple linear regression. EAS Publications Series, 66, 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1051/eas/1466005

Harris, P.A., Taylor, R., Minor, B.L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., . . . Duda, S.N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Hart, A. (2001). Mann–Whitney test is not just a test of medians: Differences in spread can be important. British Medical Journal, 323(7309), 391–393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7309.391

Hendriks, T., & Aabidien, H. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 357-390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., de Jong, J., & Bholmeijer, E. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 357–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Howlader, N., Noone, A.M., Krapcho, M., Miller, D., Brest, A., Yu, M., . . . Cronin, K.A. (2019). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2016. National Cancer Institute.

Jansen, L., Hoffmeister, M., Chang-Claude, J., Brenner, H., & Arndt, V. (2011). Benefit finding and post-traumatic growth in long-term colorectal cancer survivors: Prevalence, determinants, and associations with quality of life. British Journal of Cancer, 105(8), 1158–1165. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.335

Juul, J.S., Hornung, N., Andersen, B., Laurberg, S., Olesen, F., & Vedsted, P. (2018). The value of using the faecal immunochemical test in general practice on patients presenting with non-alarm symptoms of colorectal cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 119(4), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0178-7

Kessler, R.C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Bromet, E.J., Gureje, O., Karam, E.G., . . . Zaslavsky, A.M. (2018). The associations of earlier trauma exposures and history of mental disorders with PTSD after subsequent traumas. Molecular Psychiatry, 23(9), 1892–1899. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.194

Koutrouli, N., Anagnostopoulos, F., Griva, F., Gourounti, K., Kolokotroni, F., Efstathiou, V., . . . Potamianos, G. (2016). Exploring the relationship between posttraumatic growth, cognitive processing, psychological distress, and social constraints in a sample of breast cancer patients. Women and Health, 56(6), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2015.1118725

Lee, H.-S., Lee, S., Park, S., Baek, Y., Youn, J.-H., Cho, D.B., . . . Ko, K.-P. (2017). The association between somatic and psychological discomfort and health-related quality of life according to the elderly and non-elderly. Quality of Life Research, 27(3), 673–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1715-1

Llewellyn, C.D., Horney, D.J., McGurk, M., Weinman, J., Herold, J., Altman, K., & Smith, H.E. (2013). Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 22(1), 97–105.

Macaskill, A. (2016). Review of positive psychology applications in clinical medical populations. Healthcare, 4(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030066

Mansouri, A., Motaghedi, R., Rashidian, A., Ashouri, A., Kagrar, M., Hajibabaei, M., . . . Ansari, S. (2017). Validity and reliability assessment of the Persian version of Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 42(3), 292–300.

McNulty, J.K., & Fincham, F.D. (2012). Beyond positive psychology? American Psychologist, 67(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024572

Menger, F., Patterson, J., O’Hara, J., & Sharp, L. (2020). Research priorities on post-traumatic growth: Where next for the benefit of cancer survivors? Psycho-Oncology, 29(11), 1968–1970. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5490

Miaskowski, C., Barsevick, A., Berger, A., Casagrande, R., Grady, P.A., Jacobsen, P., . . . Marden, S. (2017). Advancing symptom science through symptom cluster research: Expert panel proceedings and recommendations. Journal of National Cancer Institute, 109(4), djw253. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw253

Mosher, C.E., & Duhamel, K.N. (2012). An examination of distress, sleep, and fatigue in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 21(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1873

Mullan, F. (1985). Seasons of survival: Reflections of a physician with cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 313(4), 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198507253130421

National Cancer Institute. (2021). Cancer stat facts: Colorectal cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

Occhipinti, S., Chambers, S.K., Lepore, S., Aitken, J., & Dunn, J. (2015). A longitudinal study of post-traumatic growth and psychological distress in colorectal cancer survivors. PLOS ONE, 10(9), e0139119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139119

Osbourne, J.W., & Waters, E. (2002). Four assumptions of multiple regression that researchers should always test. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 8(2), 1–5.

Ostertagová, E., Ostertag , O., & Kováč, J.O. (2014). Methodology and application of the Kruskal–Wallis test. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 611, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.611.115

Park, C.L., & Sinnott, S.M. (2018). Testing the validity of self-reported posttraumatic growth in young adult cancer survivors. Behavioral Sciences, 8(12), 116.

Pascoe, L., & Edvardsson, D. (2015). Psychometric properties and performance of the 17-item Benefit Finding Scale (BFS) in an outpatient population of men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(2), 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.09.004

Rasmussen, S., Larsen, P.V., Søndergaard, J., Elnegaard, S., Svendsen, R.P., & Jarbøl, D.E. (2015). Specific and non-specific symptoms of colorectal cancer and contact to general practice. Family Practice, 32(4), 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv032

Seo, E.Y., & Kwon, S. (2018). The influence of spiritual well-being, self-esteem, and perceived social support on post-traumatic growth among breast cancer survivors. Asian Oncology Nursing, 18(4), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2018.18.4.232

Sheikh-Wu, S.F., Anglade, D., Gattamorta, K., Xiao, C., & Downs, C.A. (in press). A cancer survivorship model for holistic cancer care and research. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal.

Sheikh-Wu, S.F., Anglade, D., Gattamorta, K., Xiao, C., & Downs, C.A. (2022). Symptom occurrence, frequency, and severity among colorectal cancer survivors during acute cancer survivorship. Oncology Nursing Forum, 49(5), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1188/22.ONF.421-431

Sheikh-Wu, S.F., Downs, C.A., & Anglade, D. (2020). Interventions for managing a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances during cancer survivorship: A systematic review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(4), E107–E119. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.E107-E119

Sheikh-Wu, S.F., Kauffman, M.A., Anglade, D., Shamsaldeen, F., Ahn, S., & Downs, C.A. (2021). Effectiveness of different music interventions on managing symptoms in cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 52, 101968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101968

Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., & Jemal, A. (2019). Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21551

Slanbekova, G., Chung, M.C., Abildina, S., Sabirova, R., Kapbasova, G., & Karipbaev, B. (2017). The impact of coping and emotional intelligence on the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder from past trauma, adjustment difficulty, and psychological distress following divorce. Journal of Mental Health, 26(4), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1322186

Sreedhar, J.S. (2021). Symptom occurence, severity, and self-care methods by ethnicity and age group among adults with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 48(5), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.ONF.522-534

Stark, L.L., Tofthagen, C., Visovsky, C., & McMillan, S.C. (2012). The symptom experience of patients with cancer. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 14(1), 61–70.

Tedeschi, R.G., & Calhoun, L.G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Thornton, A.A., & Perez, M.A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in prostate cancer survivors and their partners. Psycho-Oncology, 15(4), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.953

Tsai, J., El-Gabalawy, R., Sledge, W.H., Southwick, S.M., & Pietrzak, R.H. (2015). Post-traumatic growth among veterans in the USA: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans study. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714001202

Ulloa, E., Guzman, M.L., Salazar, M., & Cala, C. (2016). Post-traumatic growth and sexual violence: A literature review. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 25(3), 286–304.

Walsh, D.M.J., Groarke, A.M., Morrison, T.G., Durkan, G., Rogers, E., & Sullivan, F.J. (2018). Measuring a new facet of post traumatic growth: Development of a scale of physical post traumatic growth in men with prostate cancer. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0195992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195992

Wang, Y., Zhu, X., Yi, J., Tang, L., He, J., Chen, G., . . . Yang, Y. (2015). Benefit finding predicts depressive and anxious symptoms in women with breast cancer. Quality of Life Research, 24(11), 2681–2688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1001-z

Wen, K.-Y., Ma, X.S., Fang, C., Song, Y., Tan, Y., Seals, B., & Ma, G.X. (2017). Psychosocial correlates of benefit finding in breast cancer survivors in China. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(13), 1731–1742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316637839

Williams, A.R., Williams, D.D., Williams, P.D., Alemi, F., Hesham, H., Donley, B., & Kheirbek, R.E. (2015). The development and application of an oncology Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist for Adults (TRSC) and Children (TRSC-C) and e-health applications. BioMedical Engineering Online, 14(Suppl. 2), S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-925X-14-S2-S1

Williams, D.P., Graham, M.K., Storlie, L.D., Pedace, M.T., Haeflinger, V.K., Williams, D.D., . . . Williams, R.A. (2013). Therapy-Related Symptom Checklist use during treatments at a cancer center. Cancer Nursing, 36(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182595406

Zhang, C., Gao, R., Tai, J., Li, Y., Chen, S., Chen, L., . . . Li, F. (2019). The relationship between self-perceived burden and posttraumatic growth among colorectal cancer patients: The mediating effects of resilience. BioMed Research International, 2019, 6840743. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6840743