Empowering Lung Cancer Survivors in Post-Treatment Survivorship Care Using Participatory Action Research

Purpose: To explore the experiences of lung cancer survivors (LCSs) and their informal and professional caregivers with post-treatment care and to empower them to implement action-based study findings.

Participants & Setting: Participants were recruited using purposeful and snowball sampling from patients at a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center in the northeastern United States.

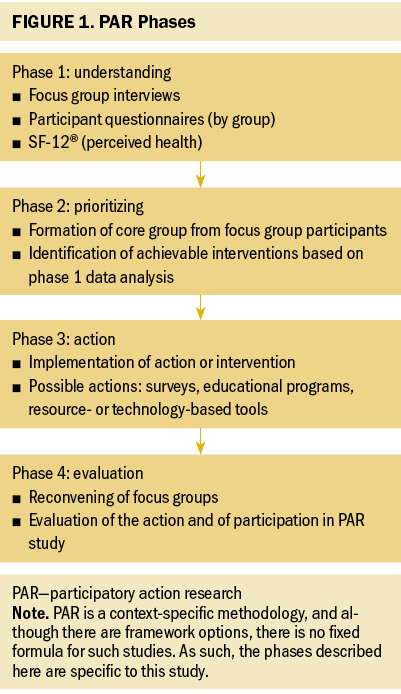

Methodologic Approach: This study used a participatory action research (PAR) four-phase design. Phase 1 was a focused ethnography; phase 2 consisted of a core group of participants deciding on an action, which was implemented in phase 3; and phase 4 consisted of an evaluation of the action.

Findings: The study found 28 categories, eight patterns, and three themes. The themes were the need for resources and education, involvement in mentoring and advocacy, and the value of living versus surviving. The action was creating two flyers focused on resources and advocacy for post-treatment support for LCSs. All participants agreed with the themes and action. Tobacco management and smoking-related stigma for LCSs were the only topics of dissent.

Implications for Nursing: Oncology nurses can use PAR to empower survivors in their post-treatment care. Future PAR cycles should focus on creating support groups and alleviating stigma for LCSs and their caregivers.

Jump to a section

In 2022, 236,740 people were estimated to have been diagnosed with lung cancer, making it the second most common cancer in the United States (Siegel et al., 2022). Improvements in lung cancer survival rates reflect several factors, including diagnostic and surgical procedures, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, improved access to care related to the Affordable Care Act, and expansion of eligibility for lung cancer screening (Siegel et al., 2022). Because of these improvements, this survivor group, which has needs not previously identified or addressed by care teams, is expected to grow (Giuliani et al., 2016; Swisher et al., 2020).

Because lung cancer survivors (LCSs) represent a small proportion of cancer survivors, research specific to their needs is not as robust as that for other cancer types. A focus on symptom management versus holistic post-treatment care may compel LCSs to seek information about healthy behaviors, smoking cessation, and social issues (McDonnell et al., 2020; Rohan et al., 2016). For these reasons, developing care models and resources specific to LCSs is vital for health systems to address any care gaps that may result in poor cancer and noncancer health outcomes.

Cancer survivorship and post-treatment care have been studied for the past three decades; however, care models remain elusive, and innovations are needed. Healthcare systems’ goals should include promoting patient-centered care, finding methods to reduce disparities, and providing coordinated survivorship care (Alcaraz et al., 2020; Yabroff et al., 2019). This study leveraged these goals by empowering LCSs, as an underrepresented survivor group, to engage in and implement immediate changes to post-treatment care. A previously published integrative review (Filchner et al., 2022) revealed the need for additional research into engagement of survivors in their own care as well as research into the interplay of their support systems, including informal and professional caregivers. In addition, the review identified eight themes or care gaps to be addressed, including relationships with healthcare providers, psychosocial issues like stigma, healthy lifestyle guidance, understanding symptoms and physical activity, and the need for care models to include self-management and use of survivorship care plans (Filchner et al., 2022). Therefore, the following research questions guided this study:

- What are the values, beliefs, and health needs of adult LCSs in the post-treatment care phase of survivorship?

- What are the priorities of LCSs, informal caregivers, and professional caregivers, and what actions can they take to promote post-treatment care?

- What are the implications for immediate change based on these priorities and actions?

The purposes of this study were to (a) explore the values, beliefs, and cancer and noncancer health needs of adult LCSs and caregivers in the post-treatment care phase of survivorship; (b) collaborate with LCSs and caregivers to develop solutions for promoting post-treatment care based on these values, beliefs, and health needs; (c) implement an action or solution developed by the researcher and coresearchers (i.e., participants); and (d) evaluate the action and participants’ experiences of the participatory action research (PAR) design.

Methods

Design

This study used a PAR design that aimed to address the problems experienced by the population of interest by involving them in identifying issues and taking action for improvement (Baum et al., 2006). In addition, this study design enabled researchers to collaborate with participants, placing them in the role of coresearchers and helping them to take ownership of their actions to solve the study problem (McIntyre, 2008). PAR studies are generally cyclical in that evaluation of the action often leads to revised or new solutions that can be implemented for immediate change. Care delivery models can be transformed by involving the affected participants in the change process (Dobrina et al., 2018). PAR is a context-specific methodology, and although there are framework options, there is no fixed formula for such studies. Therefore, this method lends flexibility to the researcher and participants (McIntyre, 2008). This study used a four-phase PAR cycle (see Figure 1). By using the PAR methodology, LCSs were able to provide input regarding their unmet needs based on their unique perspectives and to work with the researchers to develop solutions. The LCSs made decisions about which other key stakeholders to involve in finding and implementing solutions. Empowering LCSs to create their own care trajectories may improve cancer and noncancer health outcomes and help patients adhere to survivorship guidelines. Because these issues are at the forefront of decreasing cancer burden in the United States, this study may create immediate action and advance survivorship research to keep pace with the ever-growing survivor population.

Participants, Setting, and Recruitment

Study participants consisted of LCSs, their informal caregivers, and professional caregivers, who formed the culture and community for the PAR design. Participants were aged 18 years or older, were able to read and converse in English, and, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, had access to the internet and a computer or smartphone to accommodate virtual interactions. In addition, the study used the following inclusion criteria for each of the three participant groups:

- LCSs had completed initial treatment for their cancer, including any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, adjuvant immunotherapy, and targeted therapy with curative intent.

- Informal caregivers of LCSs (active or past) included family members, friends, and community-based support resources.

- Professional caregivers were healthcare providers who cared for LCSs, including physicians, nurses, advanced practice clinicians, social workers, rehabilitative practitioners, and administrators.

The study setting was a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center located in the northeastern United States. Required ethics approvals were obtained from the site’s institutional review board as well as from its nursing research and scientific review committees. Because of ongoing COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, participant interactions were conducted using a virtual platform.

Gatekeepers facilitated purposeful and snowball recruitment of participants into phase 1 (Richards & Morse, 2013). Setting gatekeepers consisted of staff in subspecialty clinics (medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgery) and members of two institution-based supportive programs. In addition, a recruitment flyer, the institutional survivorship research website, and on-hold messaging were used for recruitment. The principal investigator (PI) facilitated phase 2 recruitment by inviting participants to contribute to the development of the action based on their ability to represent their respective groups and their willingness to commit to the extra meetings and time required to complete phase 2. The PI obtained informed consent from each participant before data collection.

PAR Phase Description, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

Phase 1: This phase used focused ethnography to understand the values, beliefs, and cancer and noncancer health needs of adult LCSs. Focus groups and individual interviews were the primary data collection methods. Group-specific semistructured interview guides developed by the authors were used to elicit information from the participants. Focus group sessions and interviews were conducted until data saturation (i.e., redundancy, or the point at which no new information is gleaned) occurred to provide a thick description of post-treatment care experiences. (McFarland & Wehbe-Alamah, 2019). Thick description refers to the contextual and detailed account of the patterns of cultural and social relationships (Holloway & Galvin, 2016). Nine focus groups and interviews were conducted.

Data analysis of the focused ethnography was completed using Leininger’s ethnonursing research method (McFarland et al., 2012) and NVivo, version 12.0. Analysis began with the focus groups and individual interviews and continued throughout the study as an iterative process. First, data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed; second, data were coded; third, data codes were analyzed for patterns; and fourth, thematic interpretation and synthesis were conducted (McFarland et al., 2012). The PI conducted this data analysis with review and confirmation by all authors.

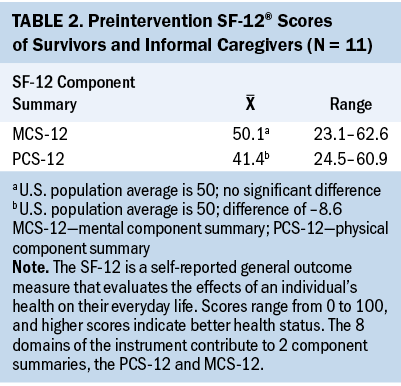

Each participant also completed an investigator-designed questionnaire specific to the participant type (i.e., LCS, informal caregiver, or professional caregiver). The questionnaire data were used for descriptive purposes and collected before the initial focus groups and interviews. Because participation in health research can affect health interventions, methods are needed to assess the effects of participation, but these are rarely described in the literature (Harris et al., 2018). In addition, proxy respondents (e.g., caregivers) may affect patient-reported outcomes in specific cancer populations because the patient may not feel healthy enough to complete the surveys; therefore, it is also essential to measure proxy health-related quality of life (QOL) (Roydhouse et al., 2018). To address this, the LCS and informal caregiver groups completed the SF-12® to assess perceived health status. The SF-12 is a self-reported general outcome measure that evaluates the effects of an individual’s health on their everyday life (Ware et al., 1996). Scores range from 0 to 100, and higher scores indicate better health status. The eight domains of the instrument contribute to two component summaries, the physical component summary (PCS-12) and the mental component summary (MCS-12).

The data collected from participant questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics and reported separately for each group. The authors scored the SF-12 using the OrthoToolKit (n.d.), an online SF-12 calculator. Each participant response generated a report with scores for the PCS-12 and MCS-12. Scores were then analyzed using descriptive statistics and compared to the mean scores of the general U.S. population.

Phase 2: Phase 2 involved reviewing and prioritizing the findings from phase 1 to develop an action. Analysis results were shared with a core working group consisting of two LCSs, one informal caregiver, one professional caregiver, and the PI. This group confirmed the final themes and used the theme data to prioritize and design the intervention (action), with guidance and feasible options developed by the authors.

Phase 3: Phase 3 was the action phase, during which the agreed-on intervention was implemented. Possible solutions included surveys, educational or resource-based offerings, technology-based tools, or self-management support. The goal was to implement an action within a three-month time frame for one PAR cycle completion.

Phase 4: The final phase was the evaluation component of the study. First, the authors developed evaluation questions based on the action taken in phase 3 and inquiries about participants’ experiences. Next, study participants reconvened into focus groups in which the PI reviewed the data analysis process and themes from phase 1, and they were asked to confirm these theme findings. Finally, the evaluation was conducted using principles of micro-interlocutor analysis (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). This method allows for counting participants as individuals in the evaluation process rather than using the focus group as a whole unit. To provide richer evaluation data, information is collected about participants’ responses, the order in which they responded, how they reacted, and any nonverbal communication they used (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009).

Findings

Sample Description

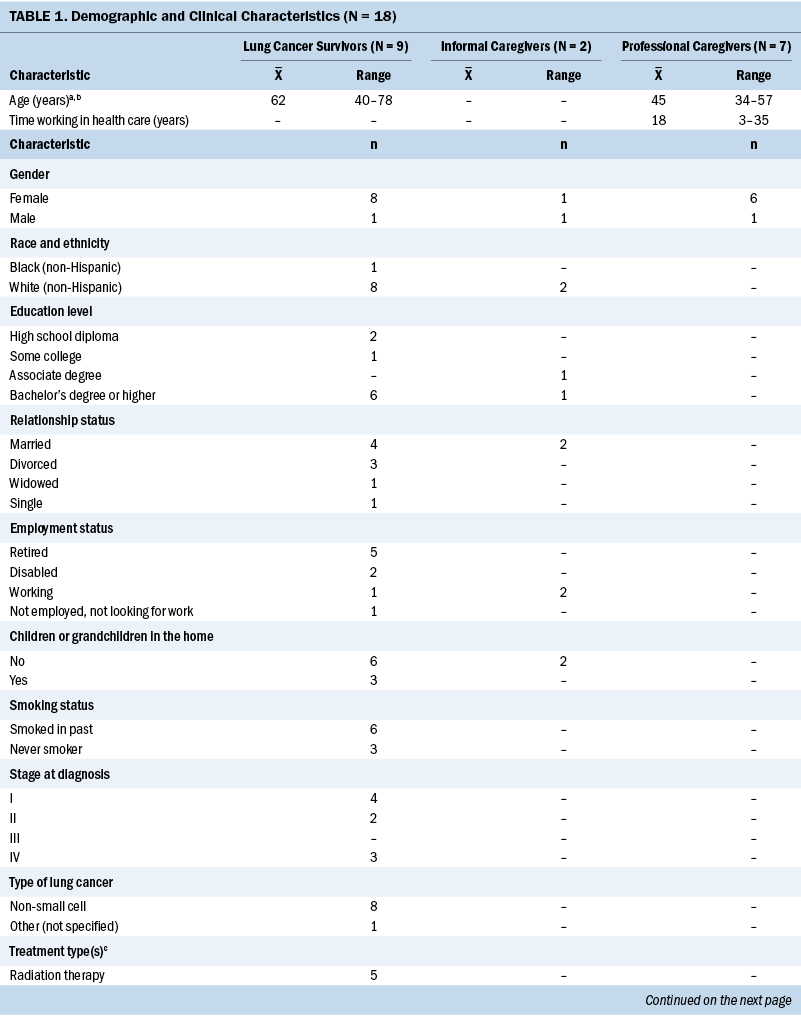

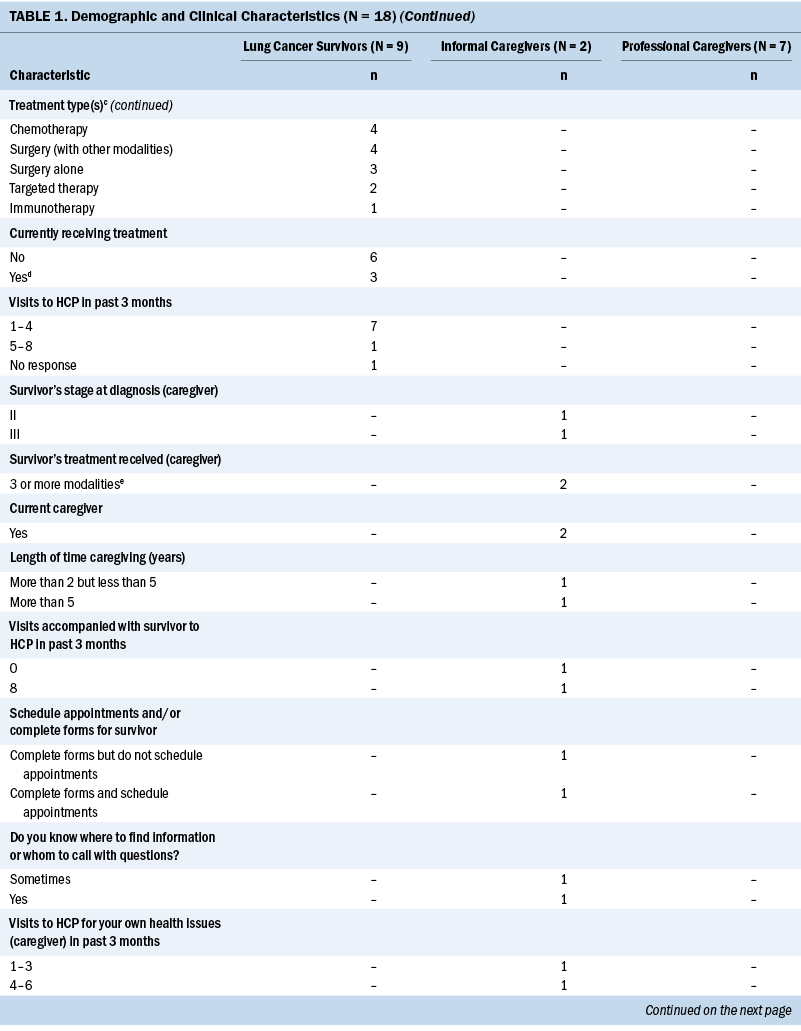

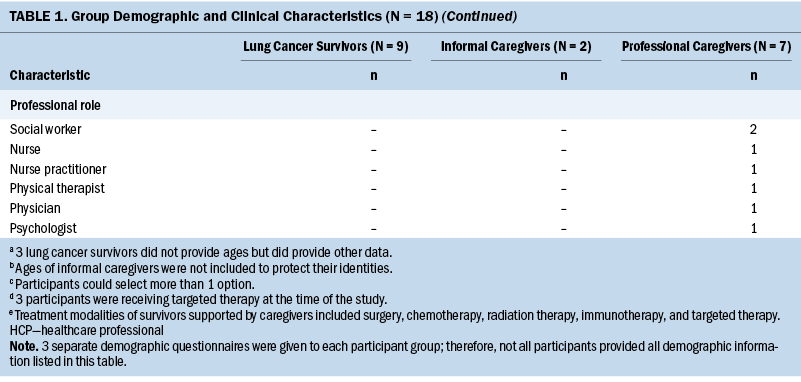

The sample was recruited over five months. The final sample (N = 18) consisted of nine LCSs, two informal caregivers, and seven professional caregivers (see Table 1). The authors used a variety of methods to increase recruitment of informal caregivers, but after only two were found, a decision was made to proceed with the available participants. The mean age of the total sample was 54 years, and most participants were female (n = 15). Mean scores for each component summary of the SF-12 are displayed in Table 2. The mean PCS-12 score of the study participants was 8.6 points lower than that of the general U.S. population. The mean MCS-12 score of the study participants was not significantly different from the general U.S. population.

Phase 1

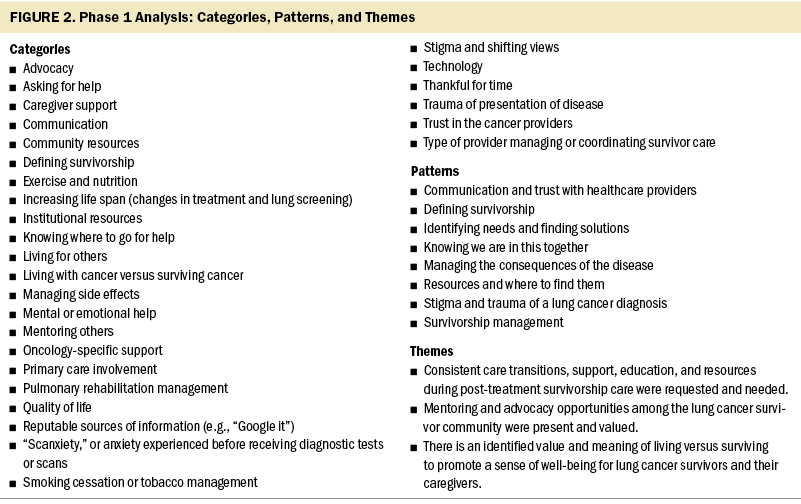

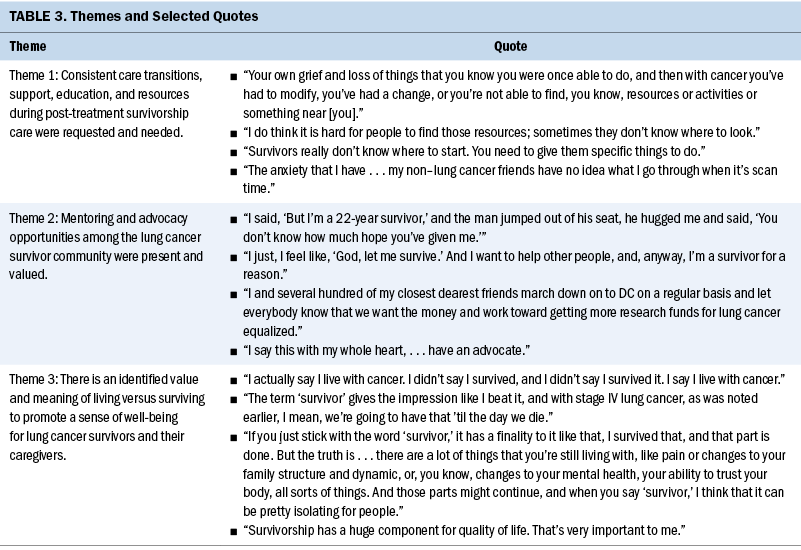

The focus group data analysis resulted in 28 categories, eight patterns, and three themes (see Figure 2). Selected quotes for each theme are displayed in Table 3.

Theme 1: need for resources and education: The first theme, in full, was, “Consistent care transitions, support, education, and resources during post-treatment survivorship care were requested and needed.” Care transitions varied depending on the participant’s stage of disease. Although early-stage survivors had no qualms about transitioning to a survivorship clinic, the later-stage survivors did not want to be transitioned. They discussed the involvement of their primary care providers and how, despite the need for these providers to be involved, survivors often sought out and deferred to their oncology providers for the management of non-oncology issues. They were vocal about this topic, which indicated this group’s need for individualized survivorship care.

Education was requested, with a focus on information about exercise and nutrition. One participant described her desire to start walking to exercise and build energy and strength. This participant had needed to seek exercise guidance on her own because it was not provided automatically as part of standard care. The discussion also included the topics of how to find reputable sources from the internet and how the practice of using internet search engines factors into finding information sources.

Information about how to access community and institutional resources was also discussed. There were varying reports from participants; some easily received information from their providers, but one participant who had moved and begun treatment at a new facility described not receiving enough information. The survivor had needed help with obtaining medications through the pharmacy and expressed frustration with the time necessary to find the proper connections. Professional caregivers described the timing of providing resource information, the volume of information to give, and how these factors are influenced by the individual needs of survivors or informal caregivers. Despite variations in the degree of support, education, or resources needed, each participant identified care gaps in these areas.

Theme 2: involvement in mentoring and advocacy: The second theme, in full, was, “Mentoring and advocacy opportunities among the LCS community were present and valued.” Regardless of participant type (i.e., LCS, informal caregiver, or professional caregiver), there was a strong desire to be involved with helping others. Some participants had initially sought help for themselves and then become mentors for others. Participants had a desire not only to help other survivors but also to become involved with improving care at the institutional level. The depth of participation in these activities ranged from simply sharing stories with other survivors in the clinic waiting room to formally voicing the need for additional research dollars from government entities. Professional caregivers participated in events to raise awareness and funds for survivors’ supportive care needs. Participants also felt compelled to combat the stigma often associated with lung cancer. They advocated to spread the message and inform the public that anyone with lungs can get lung cancer.

Theme 3: the value of living versus surviving: The third theme, in full, was, “There is an identified value and meaning of living versus surviving to promote a sense of well-being for LCSs and their caregivers.” Participants discussed using the words “survivor” and “survivorship.” There was a strong focus on living and having QOL versus surviving. Some early-stage participants described feelings of guilt and being blessed. They did not feel like survivors because they needed only surgery and were thankful that they did not have to go through other types of treatments. Participants also spoke of living for others and that the presence of grandchildren in their lives helped them recover from their treatment. Professional caregivers did not like the word “survivor” because it denotes “a battle” and stated that there should be more emphasis on thriving. However, they also relayed that because the word “survivor” is used throughout cancer care in the United States, they did not see how to move away from using it.

Within the context of living versus surviving, it was important for the survivors to be able to tell their stories. Many had experienced a traumatic medical event leading to a lung cancer diagnosis. They provided rich descriptions of how they dealt with their world “turning upside down.” For example, an informal caregiver described the loss of control from cancer, stating, “My role is to give her [the LCS] back some control.” They also explained how the changing landscape of treatments helped them survive, and they described how they are now “living with cancer.”

Trust in their healthcare providers was also crucial to participants’ overall well-being. LCSs described their emotional turmoil during the week of diagnostic tests or scans. Professional caregivers named this phenomenon “scanxiety” and described their experiences with helping survivors and informal caregivers cope. Survivors clearly stated that scan results should come only from their oncology providers versus other healthcare providers. Knowing that their provider had reviewed the scans was a source of comfort to them. Participants also discussed the need for support groups to enhance their sense of well-being throughout their cancer journey.

Stigma related to the lung cancer diagnosis was not a stand-alone theme and was part of the theme of living versus surviving, but it could reasonably be included in all three themes. LCSs felt that there has been a shift in stigmatization, particularly from healthcare providers, in that they noticed fewer assumptions being made about their smoking status. They described experiencing more interactions where the underlying belief is that anyone with lungs can get lung cancer. One participant stated, “Regardless of how you got lung cancer, we all deserve compassion and access to care.” One survivor noted, “I don’t talk about it because I’m embarrassed about it. I didn’t smoke.” Another participant stated the following about smoking stigma:

If you go back to old movies, the hero always smoked, and the women were sexy because they smoked. But they always kissed each other on the cheek good night at the door. Fast forward to modern movies, the guy lights up a cigarette and you know he is evil and is definitely the guy you’re going after, but the heroes are jumping in bed with everybody. So, which is the riskier behavior?

Phase 2

The core group convened to review the results of the data analysis and themes developed from phase 1 and to determine the action to be implemented in phase 3. The core group members confirmed the themes and decided to create two informational flyers focused on resources and advocacy. The core group members contributed the names of organizations to list on the advocacy flyer. The members also discussed which services were essential to share on the resource flyer.

Phase 3

The PI created the two flyers and worked with the care institution’s marketing department on the layout, branding, and addition of QR codes to allow direct access to specific websites. The QR codes on the resource flyer linked directly to specific resource pages on the institution’s website. The advocacy flyer’s QR codes directed users to the websites of lung cancer advocacy groups and organizations. The organizations were contacted and asked for multiple forms of communication to include on the flyer. For example, each organization provided a QR code, website link, contact name, telephone number, and email address for patients and survivors to reach out. The resource flyer was named Resource Guide for Lung Cancer Survivors and contained multiple forms of access and methods of communication (e.g., telephone number, email address, contact person). The advocacy flyer was named Lung Cancer Survivors Helping Lung Cancer Survivors and included an image of a hand holding a white ribbon representing lung cancer. The first drafts of the flyers were reviewed by the PI and the core group and were edited as needed in preparation for phase 4.

Phase 4

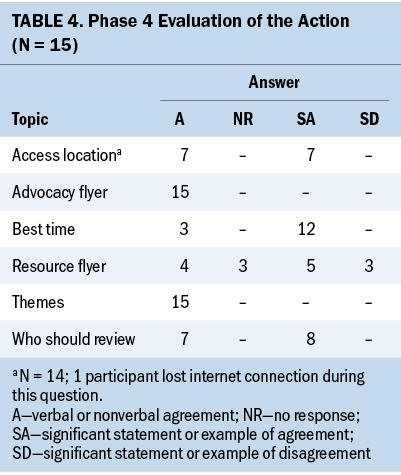

Phase 4 consisted of an evaluation of the action and experiences of the study participants. Of the original 18 participants, 15 took part in the final evaluation. Each question on the evaluation was coded as agreement, no response, significant statement for agreement, or significant statement for dissent. The counts for each question are displayed in Table 4.

The first point of the evaluation was agreement about the themes. Every participant agreed that the themes were accurate and noted the strength of the advocacy theme. The following comment summarized the group’s thoughts around this theme: “Knowing you are not the only one is important.”

The groups were explicitly asked about the design, clarity, and importance of the information provided on the flyers. Every participant agreed with the advocacy flyer’s content and layout and liked having multiple options for contacting the organizations. Some participants were unfamiliar with QR codes, and other group members walked them through how to use the codes during the meeting. One participant commented that including the QR codes was a “lifesaver” for her because she had residual neuropathy, which made typing individual letters or numbers extremely difficult and time-consuming. Another participant commented on the inclusion of the white ribbon symbol for lung cancer awareness and noted that the title and graphics were “spot-on.” The flyer and information provided immediate satisfaction for those unfamiliar with the survivor network group (which facilitated mentoring between survivors) at the study setting, as well as an opportunity to act for some participants who planned to become mentors.

The resource flyer also had support, particularly from professional caregivers. One participant who facilitated an early-stage LCS clinic expressed the desire to make the flyer a dot phrase (i.e., a shortcut) in the electronic health record so that the information would be printed out as part of the survivor’s after-visit summary. Among the LCSs and informal caregivers, there was some dissent about including information about tobacco management. On the one hand, three participants felt that including smoking information contributed to the stigma that every person with lung cancer must have been a smoker. On the other hand, another LCS made a strong argument for its inclusion, stating, “About 80% of lung cancer is caused by smoking, so why would we try to hide it? We need to provide the information for those who really need it.” One professional caregiver stated, “I’m begging you to keep the tobacco management information on the flyer.” Because there were suggestions for the addition of another resource, discussion included making the resource flyer double-sided, with four resources listed on each side, to aid with visual clarity, and there was a request to move the tobacco management information to the back side of the flyer.

Additional points made by participants during the evaluation of the flyers were when the best time was to provide them to survivors, who should provide and review them with survivors, and where they should be located or distributed (e.g., waiting rooms, education centers). Most participants wanted the flyers to be provided multiple times in the post-treatment phase of care, most wanted a nurse to provide and review the information, and most thought that the flyers should be placed in various areas of the institution for increased access. Some also suggested sending flyers to other specialists’ offices (e.g., pulmonologists), to aid in distribution.

Finally, the participants were interviewed about their experience in the PAR study. All agreed that it was a positive process that helped them appreciate the viewpoints of various stakeholders in survivorship care. Ideas for additional cycles of the PAR process included forming an LCS support group, developing an exercise program for LCSs, and creating another flyer with disease stage–specific resources. Participants were also asked about their knowledge of the Patient and Family Advisory Council at the study setting (professional caregivers were excluded). Only one of eight participants knew that this group also advocates for institutional care improvements. Additional work to promote awareness of this vital group is needed.

Discussion

This study aimed to empower LCSs and their caregivers to actively participate in meeting their post-treatment care needs using a PAR study design. Unfortunately, not many examples of such methods exist in oncology research. PAR principles are frequently used to guide focus group discussions without using a PAR framework to empower participants or implement an action (Anderson et al., 2021; Lea et al., 2018). However, this study demonstrated that using a PAR design can provide rich and meaningful data for immediate changes that can meet care needs.

The PAR process revealed that access to resources, information about advocacy, and the ability to share one’s story are essential aspects of the LCS care trajectory. The stigma of a lung cancer diagnosis continues to affect the emotional health of LCSs, as demonstrated by the discussion of including tobacco management information on the resource flyer. In previous studies, LCSs identified similar issues, such as the need for resources and the stigma associated with lung cancer (Fitch, 2020; Rohan et al., 2016). Stigmatization also exists for never-smokers and LCSs who continue to smoke.

Survivors have identified issues like the lack of advocacy organizations for LCSs as a societal problem associated with the stigma of a lung cancer diagnosis. Survivors have also encountered stigmatization from healthcare providers, which can make them uncomfortable about seeking resources for support (Lehto, 2014). In this study, advocacy and mentorship were strong themes that resonated with all participants. Advocacy groups had helped many of the participants during their journeys, and these groups continued to provide satisfaction by offering them ways to help others. Providing venues like support groups for LCSs to share their stories is important for survivors’ QOL. In a review of articles on QOL factors for LCSs, increasing social support was found to be the most critical factor for improving QOL (Hofman et al., 2021). This study confirmed the importance of social support based on the participants’ requests for support groups.

A mixed-methods study by Ross et al. (2022) used strategies to engage survivors, healthcare providers, and patient navigators to explore survivors’ post-treatment concerns. Similar to the current study, findings revealed the need for tailored resources for healthy lifestyle and psychosocial health (Ross et al., 2022). This study showed that LCS and caregiver engagement is vital to creating post-treatment care offerings that improve survivor outcomes. When survivors are given the opportunity to be heard and contribute to institutional action, it can lead to more robust and holistic post-treatment care. Using a PAR framework can facilitate these improvements.

Limitations

PAR studies are context specific; therefore, a limitation is that these findings can be used only in this study setting and are not generalizable to the entire population of LCSs and their caregivers. The participants in this study may have been more motivated to voice their concerns and become involved in advocacy activities than participants in other LCS or caregiver groups. The focused ethnography was dependent on virtual focus groups and interviews and did not include expanded observations beyond what could be seen on the screen because of the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the recruitment of informal caregivers was challenging. Although additional data from this group may have provided additional insight into post-treatment care, it is likely that the small number of informal caregivers was related to the care burden faced by this population. Finally, a more diverse group (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity) could provide an understanding of needs not identified in this study.

Nursing Implications and Future Research

The Research Agenda of the Oncology Nursing Society (Von Ah et al., 2019) prioritizes research about survivors and focuses on unique research designs to expeditiously move nursing science forward. Based on the PAR methodology, this study immediately affected post-treatment care for LCSs. There was overwhelming interest from the participants to explore forming a support group specifically for LCSs and their caregivers. Additional research is needed surrounding stigma and how it can be alleviated for LCSs. Data generated from this study can inform future PAR cycles using interprofessional teams led by nurses to coordinate and improve post-treatment care. Research supporting nurses as leaders in survivorship care is necessary and can lead to healthier outcomes for LCSs through enhanced engagement and self-management strategies. By replicating the processes and methods used in this study, nurses can implement actions tailored explicitly to LCSs and investigate their use in other cancer survivor groups or cancer care settings.

Conclusion

This study was unique because it empowered LCSs and caregivers to engage in post-treatment care. Participants were able to act immediately to make available the information about resources and advocacy that they had identified as a care gap. Using a PAR design in studies of survivorship can enrich the LCS experience and support individualized survivor care. In addition, leveraging a range of stakeholder groups (i.e., informal and formal caregivers) supports studies using the PAR method within a clinical setting.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the core group participants, who will remain anonymous to protect their privacy. It was an honor to witness and be a part of their enthusiasm to help other lung cancer survivors and caregivers.

About the Authors

Kelly Filchner, PhD, RN, OCN®, CCRC, was, at the time of this writing, director of Fox Chase Cancer Center Partners in Philadelphia, PA; Rick Zoucha, PhD, PMHCNS-BC, CTN-A, FTNSS, FAAN, is the director of nursing education, a professor, and the chair of the advanced role and PhD programs and Joan Such Lockhart, PhD, RN, CNE, ANEF, FAAN, is a professor emeritus and adjunct faculty member, both in the School of Nursing at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, PA; and Crystal S. Denlinger, MD, is senior vice president and chief scientific officer at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in Plymouth Meeting, PA. No financial relationships to disclose. Filchner completed the data collection and provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Filchner can be reached at kelly.filchner@scranton.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted December 2022. Accepted April 20, 2023.)

References

Alcaraz, K.I., Wiedt, T.L., Daniels, E.C., Yabroff, K.R., Guerra, C.E., & Wender, R.C. (2020). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21586

Anderson, J.N., Krukowski, R.A., Paladino, A.J., Graff, J.C., Schwartzberg, L., Curry, A.N., . . . Graetz, I. (2021). THRIVE intervention development: Using participatory action research principles to guide a mHealth app-based intervention to improve oncology care. Journal of Hospital Management and Health Policy, 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-103

Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

Dobrina, R., Tenze, M., & Palese, A. (2018). Transforming end-of-life care by implementing a patient-centered care model: Findings from an action research project. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 20(6), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000468

Filchner, K., Zoucha, R., Lockhart, J.S., & Denlinger, C.S. (2022). Lung cancer survivor experiences with post-treatment care: An integrative review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 49(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1188/22.ONF.167-184

Fitch, M.I. (2020). Exploring experiences of survivors and caregivers regarding lung cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Journal of Patient Experience, 7(2), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373519831700

Giuliani, M.E., Milne, R.A., Puts, M., Sampson, L.R., Kwan, J.Y.Y., Le, L.W., . . . Jones, J. (2016). The prevalence and nature of supportive care needs in lung cancer patients. Current Oncology, 23(4), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.23.3012

Harris, J., Cook, T., Gibbs, L., Oetzel, J., Salsberg, J., Shinn, C., . . . Wright, M. (2018). Searching for the impact of participation in health and health research: Challenges and methods. BioMed Research International, 2018, 9427452. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9427452

Hofman, A., Zajdel, N., Klekowski, J., & Chabowski, M. (2021). Improving social support to increase QoL in lung cancer patients. Cancer Management and Research, 13, 2319–2327. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.S278087

Holloway, I., & Galvin, K. (2016). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Lea, S., Martins, A., Morgan, S., Cargill, J., Taylor, R.M., & Fern, L.A. (2018). Online information and support needs of young people with cancer: A participatory action research study. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 9, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.2147/ahmt.s173115

Lehto, R.H. (2014). Patient views on smoking, lung cancer, and stigma: A focus group perspective. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(3), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.02.003

McDonnell, K.K., Owens, O.L., Hilfinger Messias, D.K., Friedman, D.B., Newsome, B.R., Campbell King, C., . . . Webb, L.A. (2020). After ringing the bell: Receptivity of and preferences for healthy behaviors in African American dyads surviving lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.281-291

McFarland, M.R., Mixer, S.J., Webhe-Alamah, H.B., & Burk, R. (2012). Ethnonursing: A qualitative research method for studying culturally competent care across disciplines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691201100306

McFarland, M.R., & Wehbe-Alamah, H.B. (2019). Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality: An overview with a historical retrospective and a view toward the future. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 30(6), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659619867134

McIntyre, A. (2008). Participatory action research. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385679

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Dickinson, W.B., Leech, N.L., & Zoran, A.G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800301

OrthoToolKit. (n.d.). SF-12—OrthoToolKit. https://orthotoolkit.com/sf-12

Richards, L., & Morse, J.M. (2013). ReadMe first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods (3rd ed.). Sage. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/readme-first-for-a-users-guide-to-qual…

Rohan, E.A., Boehm, J., Allen, K.G., & Poehlman, J. (2016). In their own words: A qualitative study of the psychosocial concerns of posttreatment and long-term lung cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 34(3), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2015.1129010

Ross, L.W., Townsend, J.S., & Rohan, E.A. (2022). Still lost in transition? Perspectives of ongoing cancer survivorship care needs from comprehensive cancer control programs, survivors, and health care providers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053037

Roydhouse, J.K., Gutman, R., Keating, N.L., Mor, V., & Wilson, I.B. (2018). Proxy and patient reports of health-related quality of life in a national cancer survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0823-5

Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., Fuchs, H.E., & Jemal, A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 72(1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21708

Swisher, A.K., Kennedy-Rea, S., Starkey, A., Duckworth, A., Burkart, M., Graebe, G., . . . Hudson, A. (2020). Bridging the gap: Identifying and meeting the needs of lung cancer survivors. Journal of Public Health, 30, 607–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01332-w

Von Ah, D., Brown, C.G., Brown, S.J., Bryant, A.L., Davies, M., Dodd, M., . . . Cooley, M.E. (2019). Research Agenda of the Oncology Nursing Society: 2019–2022. Oncology Nursing Forum, 46(6), 654–669. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.654-669

Ware, J., Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S.D. (1996). A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

Yabroff, K.R., Gansler, T., Wender, R.C., Cullen, K.J., & Brawley, O.W. (2019). Minimizing the burden of cancer in the United States: Goals for a high-performing health care system. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(3), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21556