Describing Self-Advocacy in Underrepresented Women With Advanced Cancer

Purpose: To describe the self-advocacy experiences of women from underrepresented groups who have advanced breast or gynecologic cancer.

Participants & Setting: To be eligible for the study, participants had to self-identify as vulnerable, which was defined as a member of a group considered at risk for poor cancer outcomes and underrepresented in clinical research.

Methodologic Approach: This descriptive, longitudinal, qualitative study consisted of one-on-one interviews of women within three months of an advanced breast or gynecologic cancer diagnosis.

Findings: 10 participants completed 25 interviews. The average age of participants was 60.2 years (range = 38–75 years). Three major themes emerged: (a) speaking up and speaking out, (b) interacting with the healthcare team, and (c) relying on support from others.

Implications for Nursing: Women with advanced cancer who are from underrepresented groups self-advocated in unique ways, learning over time the importance of how to communicate their needs and manage their healthcare team. Future research should incorporate these findings into tailored self-advocacy interventions.

Jump to a section

Self-advocacy is the ability of a patient to have their needs met when faced with a challenge. Self-advocacy behaviors include navigating complex medical systems, communicating with the healthcare team, collaborating in decision-making regarding treatment, having input regarding the impact of disease and its treatment on quality of life, and using social networks for support (Thomas et al., 2021). Self-advocating is important for individuals with advanced cancer because of their ongoing need for treatment and the common side effects and complications of cancer and treatment. Research has found that, across sociodemographic groups, women with advanced gynecologic or breast cancer who practice self-advocacy behaviors have higher quality-of-life scores on several symptom scales (Thomas et al., 2023).

Women from groups that are historically underrepresented in cancer clinical trials are often also at increased risk for poor cancer outcomes (Shariff-Marco et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2022). These groups include women of non-White race and Latina ethnicity, with a high school education or lower, an annual household income of 200% of the federal poverty level or less, and nonheterosexual sexual orientation.

Often, women from groups historically underrepresented in clinical research experience more challenges and obstacles to high-quality cancer care (Patel, Lopez, et al., 2020). Area deprivation, which is determined based on indicators such as employment, housing quality, poverty, and neighborhood-level measures of education, produces a direct negative effect on overall survival, progression-free survival, and cancer-specific survival (Unger, Moseley, et al., 2021). These findings suggest that underrepresented populations could benefit from self-advocating because of the additional challenges they experience in receiving cancer care (Gonzalez et al., 2022; Pinheiro et al., 2022; Unger, Moseley, et al., 2021; Wiltshire et al., 2006). However, there has been limited qualitative research exploring how underrepresented women with advanced cancer self-advocate.

Current conceptualizations of self-advocacy have primarily relied on homogeneous samples of women who are predominantly White, affluent, and educated (Hagan et al., 2018; Hagan & Donovan, 2013). This is a limitation because underrepresented groups are more likely to experience medical distrust, challenges in communicating with their healthcare providers, and difficulty accessing support services known to improve cancer outcomes (Asare et al., 2020; Coleman et al., 2022; Molina et al., 2015; Sutton et al., 2019). Given this gap in the literature, it is possible that current self-advocacy conceptualizations are not inclusive of individuals who may be considered underrepresented or at risk for poor cancer care outcomes because of social determinants of health.

The aims of this study are to describe self-advocacy experiences among underrepresented women with advanced breast or gynecologic cancer and to identify unique ways in which this group engages with and is challenged by self-advocacy.

Methodologic Approach

Design

The current study had a descriptive, longitudinal, qualitative design that consisted of one-on-one interviews. This is a substudy of a larger parent randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03339765) evaluating a self-advocacy serious game intervention. The parent study recruited individuals from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pennsylvania. The parent study and substudy received human subjects approval from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (STUDY19050104).

Sample

This study was conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, a large academic National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center that treats more than 113,000 patients each year. The authors recruited female participants with a recent diagnosis of advanced gynecologic or breast cancer by reviewing weekly clinic schedules and identifying all eligible participants. Potential participants were identified by research team members using participants’ self-reported sociodemographic information and the study database materials. Participants in the control and intervention arms were included. Eligibility criteria for the parent study included having a self-reported female sex, being aged 18 years or older, having a diagnosis of an advanced breast or gynecologic cancer within the past three months, and being literate in English. Individuals were excluded if they had a hospice referral at time of screening, had an active mental health disorder, or had impaired cognition. To be eligible for the current study, participants enrolled in the parent study had to self-identify as vulnerable, which was defined as a member of a group considered at risk for poor cancer outcomes and underrepresented in research based on one or more of the following qualities: non-White race, Latina ethnicity, maximum of a high school education, an annual household income of 200% of the federal poverty level or less, or nonheterosexual sexual orientation (Javier-DesLoges et al., 2022; Patel, Staples, et al., 2020; Unger, Hershman, et al., 2021). Once identified, the parent study’s research coordinator, who had an existing relationship with all study participants, emailed eligible participants to invite them to join this substudy. If interested, the research assistant contacted the participant to review the substudy aims, procedures, and risks and benefits. An additional consent form was completed by interested participants before data collection.

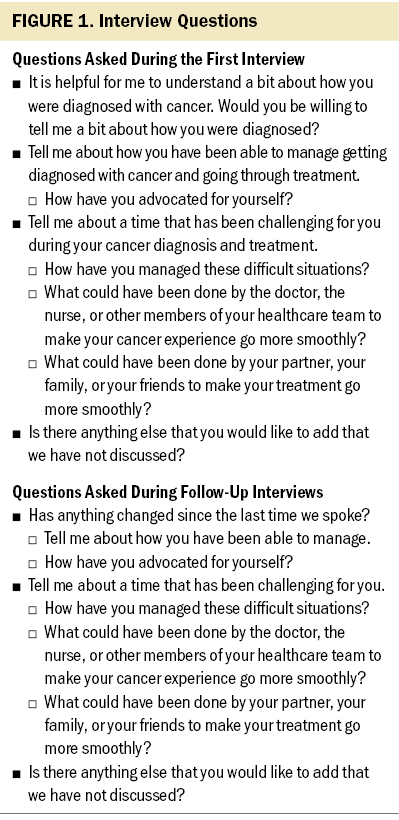

Participation consisted of three telephone interviews over six months to capture a variety of self-advocacy experiences over time. Interview questions were designed to elicit participants’ self-advocacy experiences, defined as how they addressed challenges related to their cancer care. The authors did not formally introduce a definition of self-advocacy as defined by prior research and instead focused participant responses on their lived cancer experiences. The follow-up interviews focused on any new or different experiences that had occurred since the prior interview.

Data Collection

The interview techniques described by Creswell and Poth (2017) were used to perform all participant interviews. Qualitative rigor was maintained by documenting credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability through methods including investigator field notes, bracketing of biases, triangulation of data sources, and audit trails, as per Lincoln et al. (1985).

Interviews were conducted by a female research assistant (R.B.), who was a White female undergraduate student trained in qualitative methods. Only the interviewer and participant were present for interviews. The interview questions were piloted among study team members with training in qualitative research. The participants were not provided with questions, guides, or prompts prior to the interviews. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and initially analyzed by two authors (T.H.T. and S.B.). The data analysts were a White female nurse scientist and university faculty member trained in qualitative research who has previously led similar qualitative research studies (T.H.T.) and a White female oncology physician with training and prior experience in qualitative research (S.B.).

Figure 1 presents the semistructured interview guide with questions asked at each interview time point. Prior to each interview, the interviewer briefly built rapport with the participant and emphasized the nonjudgmental nature of the individual’s experiences with self-advocacy. Confidentiality was also stressed to ensure that participants felt comfortable discussing their experiences. All interviews occurred remotely, via telephone, and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews lasted about 20–40 minutes, were audio recorded, and were transcribed verbatim using TranscribeMe.com. Participants were compensated with a $25 prepaid debit card for completing each interview.

Analysis

The investigators individually reviewed and coded the transcripts before meeting to discuss and compare coding. A descriptive content analysis method was used, including an iterative constant comparison approach using axial coding techniques (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Initial themes and subthemes were extracted from the transcripts and discussed by the authors using an iterative process and shared with an additional Black female nurse scientist (S.G.) for relevancy and clarity (Morse, 2008). Variations in opinions among the authors were resolved via discussion until consensus was met. The transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or review. The authors did not use software to assist with qualitative data analysis.

In accordance with thematic analysis procedures, the authors classified categories of responses into overarching themes as well as underlying subthemes. When data saturation of themes and subthemes was reached (i.e., no new themes or subthemes were discovered), recruitment ceased. Final themes and subthemes were reviewed and finalized by all authors to ensure consistency. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (Tong et al., 2007) guided the presentation of results.

Findings

Between December 2019 and April 2020, 10 of the 31 parent study participants eligible for the substudy consented and completed substudy procedures. Eighteen participants did not respond to three email invitations from the research coordinator, two declined to participate, and one died prior to being contacted. Twenty-five interviews were completed in total, with participants (N = 10) completing a total of one (n = 2), two (n = 1), or three (n = 7) interviews.

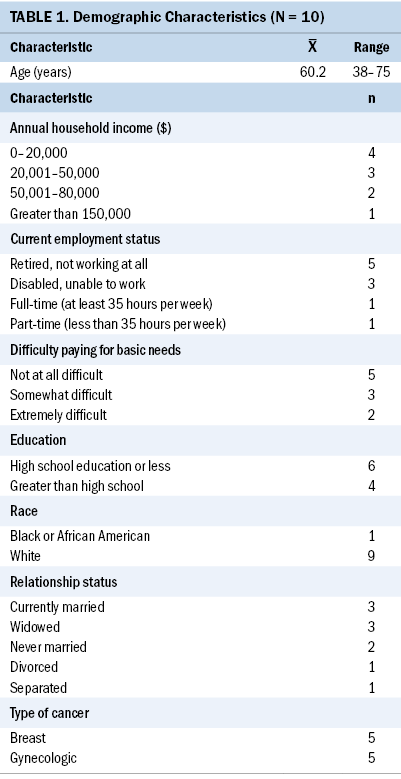

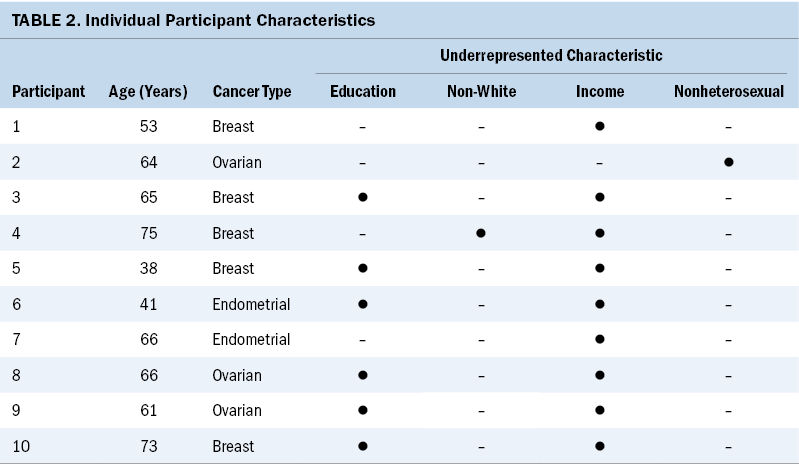

Table 1 reports the health and sociodemographic information of participants, and Table 2 lists individual participants’ information. The average age of participants was 60.2 years, with a range of 38–75 years. Most participants were White (n = 9), married (n = 3) or widowed (n = 3), and retired (n = 5). Half of the participants had breast cancer (n = 5), and the other half had a gynecologic cancer (n = 3 ovarian; n = 2 endometrial). Nine participants were considered vulnerable based on household income, six based on education, one based on race, and one based on sexual orientation. Seven participants met criteria for two of these categories. Six participants received the intervention arm of the parent study and four participants did not.

Themes and Subthemes

The analysis revealed the following major themes with corresponding subthemes of self-advocacy among underrepresented women with advanced cancer: (a) speaking up and speaking out, (b) interacting with the healthcare team, and (c) relying on support from others.

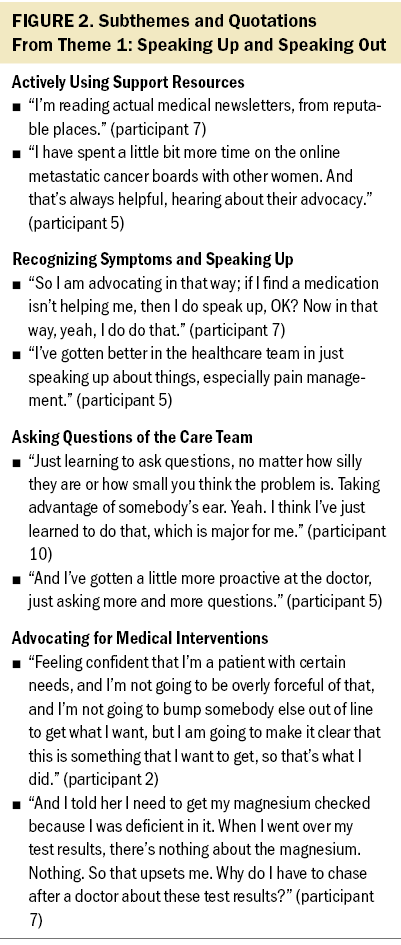

Theme 1: speaking up and speaking out: This theme was divided into four subthemes: actively using support resources, recognizing symptoms and speaking up, asking questions of the care team, and advocating for medical interventions. Representative quotations for each subtheme are presented in Figure 2. Participants self-advocated by being upfront about their needs. They used the internet and support groups to learn more about their disease processes and to advocate based on these resources. Using these resources encouraged participants to ask more questions of their care team, which was also frequently cited as a form of self-advocacy. In addition, half of the participants reported self-advocacy in the form of requesting medical interventions, whether imaging for a suspected recurrence, continuation of chemotherapy, or obtaining of additional laboratory values.

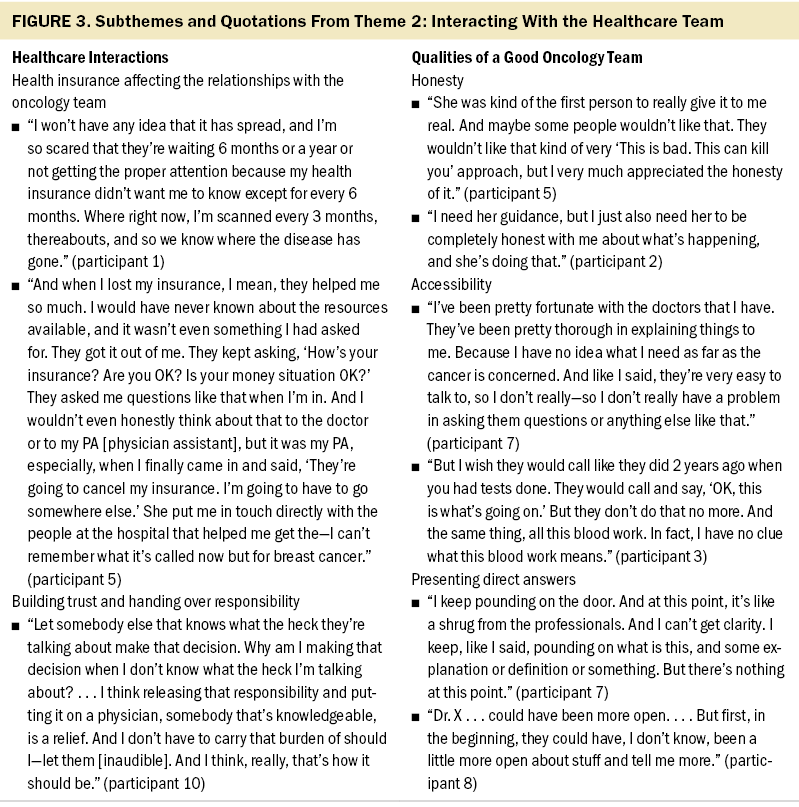

Theme 2: interacting with the healthcare team: This theme was divided into two subthemes: healthcare interactions, which was further divided into the two subthemes of health insurance affecting the relationships with the oncology team, and building trust and handing over responsibility; and qualities of a good oncology team, which was further divided into the three subthemes of honesty, accessibility, and presenting direct answers. Representative quotations for each subtheme are provided in Figure 3. Participants’ efforts to self-advocate led to frustration in their attempts to understand and manage the complex structures of the entire oncology team. One participant summed up her confusion by stating, “Who’s who in the zoo, and who do you call?” Two participants discussed the impact of health insurance and costs of their treatment and surveillance on their ability to self-advocate. One of these participants was grateful to have healthcare team members who addressed health insurance concerns preemptively, and the other participant noted concern that health insurance would affect her ability to have continued imaging surveillance and care from her team. Finally, one participant felt that she self-advocated by putting the burden of responsibility of caring for her disease onto the physician, noting “a relief” when letting “somebody that’s knowledgeable” take complete control.

Participants preferred specific qualities in their healthcare team that made it easier to self-advocate, including honesty, accessibility, and directness. Three participants cited honesty from their care team as being a key component to good care. One participant focused on the importance of support from her team, noting she has “care from them, from the whole team, from my doctor to the nurses to everybody in the office.” Two participants appreciated easy accessibility to their care team, particularly when it came to asking questions. Finally, two participants expressed a preference for direct answers from their providers, even when the answer was not desirable.

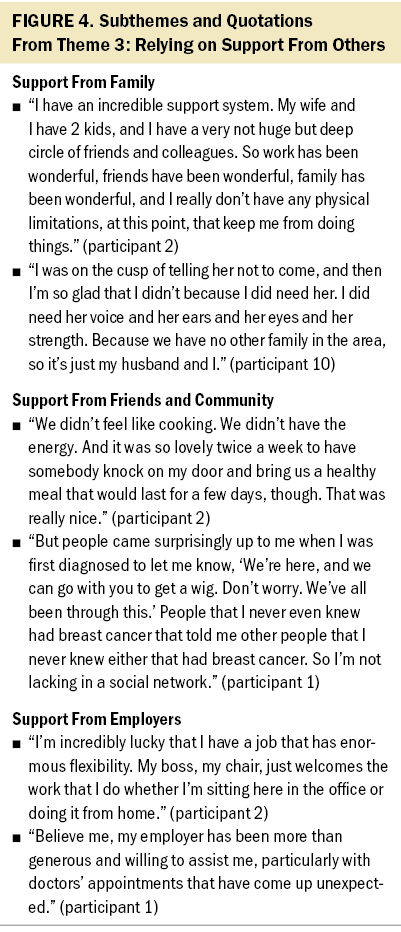

Theme 3: relying on support from others: This theme was divided into three subthemes: support from family, support from friends and community, and support from employers. Representative quotations for each subtheme are presented in Figure 4. Participants spoke of advocacy through allowing their social networks to support and care for them during their treatment. Four women spoke about their family members, three spoke about their friends and the community of fellow individuals with cancer, and two spoke of their employers. One participant noted self-advocacy in regard to to day-to-day life, recognizing that she had “nobody else that can handle this stuff for me, so I have to try and be on top of it.”

Discussion

This study uncovered the self-advocacy needs and behaviors of underrepresented women with advanced cancer diagnoses, demonstrating that women engaged in self-advocacy to ensure that their values, needs, and priorities were addressed by their healthcare teams. The authors found three main themes through which women self-advocated in the face of a serious diagnosis: (a) speaking up and speaking out (i.e., directly advocating for their needs), (b) interacting with the healthcare team, and (c) relying on support from others. By addressing weaknesses in prior research that relied on quantitative measures of self-advocacy among broad groups of mostly White, affluent, and well-educated women, this study begins to differentiate the self-advocacy needs and behaviors of women from diverse backgrounds.

Results demonstrated that women from groups that have traditionally been underrepresented in cancer research primarily self-advocated by speaking up about symptoms, asking questions of the care team, and requesting specific medical interventions. Participants were acutely aware that their oncologists were caring for other patients, and they frequently mentioned the importance of respecting their oncologists’ time so that others could receive care. In contrast, a cross-sectional study of 78 participants with advanced breast or gynecologic cancer in which only one-third of the participants identified as vulnerable found that some women self-advocated by “pushing back” against their oncologist and felt entitled to direct their care (Thomas et al., 2023).

Participants in the current study expressed an overwhelming sense of appreciation for and trust in the oncology teams, and there was no expression of distrust necessitating the need to push back. Parallel findings of high trust and better-quality communication among individuals from lower socioeconomic status and underrepresented groups have been reported among patients with chronic life-limiting illnesses (Coats et al., 2018). Participants’ awareness of the complexities of the medical system and appreciation for the entire oncology team may facilitate collaboration with the team, but they may also indicate hesitation or uncertainty regarding how to alert the healthcare team of any unmet needs. This finding might have been different if more women of color had been included, considering concerns related to stigma, bias, and mistrust frequently experienced by these women and the tendency for Black women with these cancers to silence their concerns (Madlock Gatison, 2015; Palmer Kelly et al., 2021; WhiteMeans & Osmani, 2017). It may also represent lower expectations that some women have based on their cumulative experiences interacting within a healthcare system traditionally dismissive of their needs. In addition, although information-seeking behavior has previously been described in the literature, little has been written specifically about this behavior in underrepresented patients (Adamson et al., 2018). Continuing to explore preferred methods of healthcare communication among patients from underrepresented groups may lead to more self-advocacy in this population (Fareed et al., 2021).

Women frequently relied on their social networks to focus on treatment and recovery. This ranged from knowledge sharing to emotional support to physical assistance and was an important aspect of self-advocacy in this participant population. Survivor advocates are important allies for patients from underrepresented groups when undergoing screening or treatment for cancer. By assisting women in navigating the healthcare system, survivor advocates are able to encourage self-advocacy among underrepresented women (Molina et al., 2022). In this study, it was evident that fellow cancer survivors played an important role in participants’ ability to self-advocate. Encouraging underrepresented patients with advanced cancer to partner with survivor advocates may have a positive, multilevel impact on cancer care disparities (Jackson et al., 2021; Newman & Jackson, 2009).

Although most efforts to promote self-advocacy have focused on improving health literacy and communication with healthcare teams, the findings of the current study identify additional aspects of self-advocacy that contribute to the care and quality of life of underrepresented women with an advanced cancer diagnosis. Building supportive collaborations with their healthcare providers and encouraging their abilities to speak out and seek support can further enhance their self-advocacy. By recognizing and understanding the importance of supporting these women in different facets of their lives, the healthcare team will be able to better support self-advocacy behaviors in their patients with advanced cancer.

Limitations

There were several limitations noted with this study. First, this qualitative study occurred within an intervention trial so it is unclear whether self-advocacy skills existed prior to participation or were learned during the intervention. Second, this was a relatively small qualitative study that was performed at a single institution. Third, all underrepresented statuses were combined together, so the study does not directly tie specific experiences to specific groups of women. Fourth, the study design did not include accounts from healthcare providers whose behaviors and affect are known to influence how individuals engage in self-advocacy behaviors such as communication and relationship building (Siminoff et al., 2006). Despite these limitations, this study adds to the growing body of literature on forms of self-advocacy among underrepresented women with advanced cancer. In addition, future research should focus on having study team members who represent the group being interviewed to ensure that data are collected and analyzed in a culturally congruent manner.

Implications for Nursing

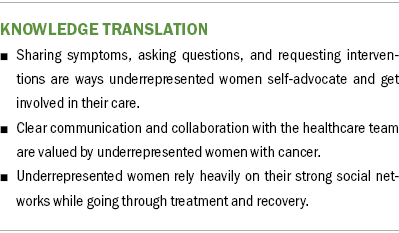

Underrepresented women with advanced cancer value clear communication and collaboration with their healthcare teams. This reflects prior research describing self-advocacy among broad groups of women with cancer and is also consistent with prior research suggesting women prefer to actively participate in their cancer care (Schuler et al., 2017; Yennurajalingam et al., 2018). Underrepresented women are at high risk for poor patient–clinician communication, and healthcare providers should focus on open communication strategies (PérezStable & El-Toukhy, 2018).

Conclusion

Underrepresented women diagnosed with advanced-stage gynecologic or breast cancer engage in several self-advocacy behaviors to ensure that their cancer needs are met. These behaviors include directly advocating for their needs, working closely with their oncology team, and relying on others for support. Future research should untangle how specific groups of women with advanced cancer self-advocate to appreciate how race, socioeconomic status, disability, gender identity, and other social factors affect the need for individuals to self-advocate and the implications of doing so, given that these interventions can be tailored to specific patient populations.

About the Authors

Sarah Bell, MD, is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the Division of Gynecologic Oncology in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Magee-Womens Hospital, Rachel Bergeron, BSN, RN, is a nurse at Aya Healthcare in Pittsburgh, and Patricia Jo Murray, PhD, is a project coordinator and researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, all in Pennsylvania; Shena Gazaway, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; and Teresa Hagan Thomas, PhD, RN, is an associate professor in the Department of Health Promotion and Development in the School of Nursing and a member of the Palliative Research Center in the School of Medicine, both at the University of Pittsburgh. This research was supported, in part, by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Award (MSRG-18-051-51; principal investigator: Thomas), a National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Award, and a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R37 CA262025). Bergeron and Thomas contributed to the conceptualization and design and provided statistical support. Bergeron, Murray, and Thomas completed the data collection. Bell, Bergeron, Gazaway, and Thomas contributed to the manuscript preparation. All authors provided the analysis. Dr. Bell can be reached at bellsg@upmc.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2023. Accepted June 5, 2023.)

References

Adamson, M., Choi, K., Notaro, S., & Cotoc, C. (2018). The doctor–patient relationship and information-seeking behavior: Four orientations to cancer communication. Journal of Palliative Care, 33(2), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718759881

Asare, M., Fakhoury, C., Thompson, N., Culakova, E., Kleckner, A.S., Adunlin, G., . . . Kamen, C.S. (2020). The patient–provider relationship: Predictors of Black/African American cancer patients’ perceived quality of care and health outcomes. Health Communication, 35(10), 1289–1294.

Coats, H., Downey, L., Sharma, R.K., Curtis, J.R., & Engelberg, R.A. (2018). Quality of communication and trust in patients with serious illness: An exploratory study of the relationships of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and religiosity. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 56(4), 530–540.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.07.005

Coleman, D., Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A., Montero, A., Sawhney, S., Wang, J.H.-Y., Lobo, T., & Graves, K.D. (2022). Stigma, social support, and spirituality: Associations with symptoms among Black, Latina, and Chinese American cervical cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01283-z

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

Creswell, J.W., & Poth, C.N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Fareed, N., Swoboda, C.M., Jonnalagadda, P., Walker, D.M., & Huerta, T.R. (2021). Differences between races in health information seeking and trust over time: Evidence from a cross-sectional, pooled analyses of HINTS data. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120934609

Gonzalez, N., Mead, K.H., Pratt-Chapman, M.L., & Arem, H. (2022). Healthcare utilization in cancer survivors: Six-month longitudinal cohort data. Cancer Causes and Control, 33(7), 1005–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01587-6

Hagan, T.L., Cohen, S.M., Rosenzweig, M.Q., Zorn, K., Stone, C.A., & Donovan, H.S. (2018). The Female Self-Advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale: A validation study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(4), 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13498

Hagan, T.L., & Donovan, H.S. (2013). Ovarian cancer survivors’ experiences of self-advocacy: A focus group study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40(2), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.ONF.A12-A19

Jackson, K., Waters, M., & Newman, L.A. (2021). Sisters network, inc.: The importance of African American survivor advocates in addressing breast cancer disparities. Current Breast Cancer Reports, 13(2), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-021-00404-4

Javier-DesLoges, J., Nelson, T.J., Murphy, J.D., McKay, R.R., Pan, E., Parsons, J.K., . . . Rose, B.S. (2022). Disparities and trends in the participation of minorities, women, and the elderly in breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer clinical trials. Cancer, 128(4), 770–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33991

Lincoln, Y.S., Guba, E.G., & Pilotta, J.J. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 9(4), 438–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

Madlock Gatison, A. (2015). The pink and black experience: Lies that make us suffer in silence and cost us our lives. Women’s Studies in Communication, 38(2), 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2015.1034628

Molina, Y., Hempstead, B.H., Thompson-Dodd, J., Weatherby, S.R., Dunbar, C., Hohl, S.D., . . . Ceballos, R.M. (2015). Medical advocacy and supportive environments for African-Americans following abnormal mammograms. Journal of Cancer Education, 30(3), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0732-9

Molina, Y., Strayhorn, S.M., Bergeron, N.Q., Strahan, D.C., Villines, D., Fitzpatrick, . . . Khanna, A.S. (2022). Navigated African American breast cancer patients as incidental change agents in their family/friend networks. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(3), 2487–2496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06674-z

Morse, J.M. (2008). Confusing categories and themes. Qualitative Health Research, 18(6), 727–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230831493

Newman, L.A., & Jackson, K.E. (2009). The sisters network: A national African American breast cancer survivor advocacy organization. Journal of Oncology Practice, 5(6), 313–314. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.091037

Palmer Kelly, E., McGee, J., Obeng-Gyasi, S., Herbert, C., Azap, R., Abbas, A., & Pawlik, T.M. (2021). Marginalized patient identities and the patient-physician relationship in the cancer care context: A systematic scoping review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(12), 7195–7207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06382-8

Patel, M.I., Lopez, A.M., Blackstock, W., Reeder-Hayes, K., Moushey, E.A., Phillips, J., & Tap, W. (2020). Cancer disparities and health equity: A policy statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(29), 3439–3448. https://doi.org/10.1200%2FJCO.20.00642

Patel, S.N., Staples, J.N., Garcia, C., Chatfield, L., Ferriss, J.S., & Duska, L. (2020). Are ethnic and racial minority women less likely to participate in clinical trials? Gynecologic Oncology, 157(2), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.01.040

Pérez-Stable, E.J., & El-Toukhy, S. (2018). Communicating with diverse patients: How patient and clinician factors affect disparities. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(12), 2186–2194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.021

Pinheiro, L.C., Reshetnyak, E., Akinyemiju, T., Phillips, E., & Safford, M.M. (2022). Social determinants of health and cancer mortality in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort study. Cancer, 128(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33894

Schuler, M., Schildmann, J., Trautmann, F., Hentschel, L., Hornemann, B., Rentsch, A., . . . Schmitt, J. (2017). Cancer patients’ control preferences in decision making and associations with patient-reported outcomes: A prospective study in an outpatient cancer center. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(9), 2753–2760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3686-8

Shariff-Marco, S., Yang, J., John, E.M., Kurian, A.W., Cheng, I., Leung, R., . . . Gomez, S.L.. (2015). Intersection of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status in mortality after breast cancer. Journal of Community Health, 40(6), 1287–1299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0052-y

Siminoff, L.A., Graham, G.C., & Gordon, N.H. (2006). Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: Disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Education and Counseling, 62(3), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011

Sutton, A.L., He, J., Edmonds, M.C., & Sheppard, V.B. (2019). Medical mistrust in black breast cancer patients: Acknowledging the roles of the trustor and the trustee. Journal of Cancer Education, 34(3), 600–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1347-3

Taylor, D.B., Osazuwa-Peters, O.L., Okafor, S.I., Boakye, E.A., Kuziez, D., Perera, C., . . . Osazuwa-Peters, N. (2022). Differential outcomes among survivors of head and neck cancer belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups. JAMA Otolaryngology, 148(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.3425

Thomas, T.H., Donovan, H.S., Rosenzweig, M.Q., Bender, C.M., & Schenker, Y. (2021). A conceptual framework of self-advocacy in women with cancer. Advances in Nursing Science, 44(1), E1–E13. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000342

Thomas, T.H., Taylor, S., Rosenzweig, M., Schenker, Y., & Bender, C. (2023). Self-advocacy behaviors and needs in women with advanced cancer: Assessment and differences by patient characteristics. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(2), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10085-7

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Unger, J.M., Hershman, D.L., Till, C., Minasian, L.M., Osarogiagbon, R.U., Fleury, M.E., & Vaidya, R. (2021). “When offered to participate”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient agreement to participate in cancer clinical trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 113(3), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa155

Unger, J.M., Moseley, A.B., Cheung, C.K., Osarogiagbon, R.U., Symington, B., Ramsey, S.D., & Hershman, D.L. (2021). Persistent disparity: Socioeconomic deprivation and cancer outcomes in patients treated in clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39(12), 1339–1348. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02602

White-Means, S.I., & Osmani, A.R. (2017). Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication with breast cancer patients: Evidence from 2011 MEPS and experiences with cancer supplement. Inquiry, 54, 46958017727104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017727104

Wiltshire, J., Cronin, K., Sarto, G.E., & Brown, R. (2006). Self-advocacy during the medical encounter: Use of health information and racial/ethnic differences. Medical Care, 44(2), 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000196975.52557.b7

Yennurajalingam, S., Rodrigues, L.F., Shamieh, O.M., Tricou, C., Filbet, M., Naing, K., . . . Bruera, E. (2018). Decisional control preferences among patients with advanced cancer: An international multicenter cross-sectional survey. Palliative Medicine, 32(4), 870–880. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317747442