A Multimethod Evaluation of a Specialist Breast Care Nurse–Led Survivorship Clinic in Australia

Objectives: To compare the needs and issues faced by breast cancer survivors (BCSs) who received chemotherapy as part of their treatment with those who did not and assess satisfaction with a specialist breast care nurse–led survivorship clinic.

Sample & Setting: BCSs who attended a specialist breast care nurse–led survivorship clinic at a Western Australian private, not-for-profit hospital.

Methods & Variables: A multimethod evaluation included surveys, quality-of-life assessments, and reviews of wellness plans.

Results: A total of 68 BCSs participated; the majority had received chemotherapy as part of their treatment and were female. BCSs experienced a diverse range of issues. Significant differences were found between chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy groups for financial difficulties (p = 0.002), body image (p = 0.017), future perspective (p = 0.022), and arm symptoms (p = 0.007). Participants indicated that the specialist breast care nurse–led clinic was appropriately timed and highly valued.

Implications for Nursing: Specialist breast care nurse–led clinics can identify and address BCSs’ ongoing needs.

Jump to a section

Cancer survivorship refers to life after diagnosis, living well and optimizing “health of body and mind for life” (Brennan et al., 2008, p. 826). The five-year relative survival rate from early breast cancer in Australia improved from 73% in 1989 to 92% in 2022 (Breast Cancer Trials, n.d.). As survival rates improve post–cancer diagnosis, there is growing recognition of the need for supportive cancer survivorship care (Halpern et al., 2015; Porter-Steele et al., 2017) beyond active treatment, usually defined as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy (All.Can, 2019). In this context, there has been a shift in the definition of survivorship. The Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (2016) added the term wellness to emphasize living well. This incorporates physical, psychological, and economic outcomes focusing on the survivors’ priorities and how they wish to live their life using a person-centered holistic approach. The term survivorship incorporates the time from end of primary treatment to living beyond cancer (Clinical Oncology Society of Australia, 2016). Support can be delivered via visits with clinicians, primary caregivers, and specialist nurses, or via peer support from other cancer survivors. Follow-up may include face-to-face consultations or telephone sessions individually or within a group setting (Gast et al., 2017; Porter-Steele et al., 2017).

Reviews of breast cancer survivorship care models vary from traditional oncology specialist follow-up, shared care with general practitioners, and specialist breast care nurse (SBCN)–led care (Meade et al., 2017; Post et al., 2017; Radhakrishnan et al., 2019). Studies have reported that women value survivorship care and have commented on who is best to deliver this care (Meade et al., 2017; Post et al., 2017; Radhakrishnan et al., 2019). Barriers in survivorship care can be related to the type of relationship between health professionals and breast cancer survivors (BCSs), in particular opportunities to discuss sensitive issues such as sexual health and financial burdens related to survivorship (Canzona et al., 2019; Radhakrishnan et al., 2019). Little is published on the experiences of BCSs who have attended an SBCN-led survivorship clinic, comparing the needs of those who have received chemotherapy and those who have not. In addition, studies are limited on whether unmet needs of BCSs, including psychosocial issues, fear of cancer recurrence, changes in sexual relationships, and physical consequences such as fatigue and financial stress, can be adequately identified in this setting (Lisy et al., 2019; Peate et al., 2021).

There is evidence that BCS satisfaction with care is dependent on specialist knowledge, continuity of care, trusted relationships between patients and their treating team, accessibility and cost of supportive care, and availability of individualized care plans (Brédart et al., 2016; Meade et al., 2017; Radhakrishnan et al., 2019; Saltbæk et al., 2019) that can reduce confusion in ongoing follow-up care recommendations. Individualized survivorship care plans allow BCSs to report issues and concerns and set personal goals (Meade et al., 2017). BCSs strongly preferred their general practitioners and specialist nurses to have knowledge and oncology training in providing support for issues related to treatment and maintaining healthy lifestyle recommendations (Halpern et al., 2015). Patient preference studies suggest that holistic, consistent, and coordinated individual management is valued by BCSs (Kwan et al., 2019; Meade et al., 2017; Saltbæk et al., 2019).

BCSs reportedly felt SBCNs were more accessible and approachable compared to general practitioners when discussing sensitive issues relating to sexuality, emotional concerns, anxiety, and fear of recurrence (Kozul et al., 2020; Porter-Steele et al., 2017). Part of the SBCN role is to provide a conduit between individuals with breast cancer and their treating specialists (Porter-Steele et al., 2017). SBCNs who have been involved in a patient’s breast cancer journey establish a relationship with the patient, have specialist knowledge of their treatment, and are well placed to be involved in the transition to survivorship. This enables continuity of care together with an individualized survivorship care plan and can facilitate communication between the BCS and their interprofessional team (Meade et al., 2017; Porter-Steele et al., 2017; Radhakrishnan et al., 2019). Individual consultation with an SBCN has been demonstrated to improve patients’ knowledge about their breast cancer diagnosis and provide greater psychological and practical support (Brown et al., 2018). Based on the growing evidence of the value of the SBCN role in cancer survivorship, a Wellness After Breast Cancer Clinic (WABCC) was established as an SBCN-led clinic in November 2017.

Objectives

The aims of this study were to identify the issues BCSs experienced and to establish whether BCSs were satisfied with the WABCC. The objectives of the study were to (a) compare the needs and issues faced by BCSs who received chemotherapy as part of their treatment with those who did not and (b) assess BCS satisfaction with an SBCN-led clinic.

Theoretical Framework

The Assessing the Impact of Disease framework (Finlayson et al., 2004) was adopted as the theoretical framework for this study. The framework emphasizes the importance of considering the full impact of disease on the individual and that the effects of illness extend beyond physical functioning. To ensure that other aspects such as emotional and social functioning are assessed, the framework proposes that symptoms, disease severity, and health-related quality of life (QOL) should be measured. These three elements were incorporated into this study to assess the impact of disease in the context of BCSs attending an SBCN-led clinic and are also in keeping with a holistic nursing approach.

Methods and Variables

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline (von Elm et al., 2007) was used to report this study. A multimethod approach including surveys, QOL assessments, and reviews of wellness plans were used to evaluate the WABCC and address the study objectives.

Sample and Setting

The study was undertaken at a 578-bed metropolitan private, not-for-profit tertiary hospital, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, in Western Australia. The study hospital has a comprehensive cancer service that provides diagnostic, surgical, reconstructive surgery, oncologic, and allied health services for patients diagnosed with breast cancer, treating more than 200 patients per year, supported by an interprofessional breast cancer team and an active research portfolio. The SBCN-led WABCC is held weekly. BCSs who had surgery and received and completed any form of active treatment (i.e., radiation therapy, endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy) for their breast cancer diagnosis were invited to attend the WABCC for a face-to-face consultation.

Model of Survivorship

The clinic’s vision is to educate BCSs about risk reduction strategies, reinforce surveillance plans, promote preventive health, and alleviate further financial toxicity related to out-of-pocket medical costs and loss of income because of breast cancer treatment. In addition, the WABCC’s goal is to help BCSs and families better understand longer-term consequences of a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on BCSs’ QOL.

Study Recruitment

All BCSs who attended the WABCC from November 6, 2017, to June 20, 2019, were emailed by the lead researcher (G.R.) with a participant information sheet that outlined the purpose of the study. Contact details were provided, and potential participants had the opportunity to ask questions about the research or opt out of the study. A flyer was also placed in the WABCC to inform potential participants of the study. BCSs who were aged 18 years or older, were of any gender, and had surgery alone or had received any type of adjuvant or neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment (i.e., radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or endocrine therapy) in addition to surgery were eligible to participate. Metastatic disease progression was an exclusion criterion for participation in the study.

Data Collection

QOL

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), version 3.0, and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire–Breast Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-BR23), version 1.0, were used to assess QOL. Both tools are widely reported in the literature and are validated and reliable for use with patients with breast cancer (Nguyen et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2014). Questionnaires were emailed to BCSs one week prior to their one-on-one consultation with the SBCN. The EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3.0, is designed to assess the QOL of individuals with cancer and includes functional scales such as physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social functioning and 13 items related to symptoms including fatigue, nausea, and pain (EORTC, 1995). A high score on the functional scale constitutes a higher level of function, and a high score on the symptomatic scale indicates increasing severity of the symptom experienced. For the two items related to overall health and QOL, a higher score represents a better QOL. In addition, the EORTC QLQ-BR23, version 1.0, breast cancer–specific QOL assessment tool was administered. This consists of eight items that assess functional scales related to body image and sexual functioning and 15 symptom scales related to systemic therapy side effects and breast and arm symptoms (EORTC, 1994).

Wellness Plan

Data were collected from standardized checklists completed during clinic visits by the SBCN, including information on lifestyle, financial, and fertility issues, and family relationships. Data were also collected from summary reports of each patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment with a detailed wellness plan to manage treatment-associated symptoms, monitor cancer recurrence, and promote preventive health. The wellness plans were provided to BCSs and their immediate healthcare providers.

Patient Satisfaction Survey

A seven-item anonymous patient satisfaction questionnaire was distributed electronically to BCSs to assess satisfaction with the service and use of other support services. An open-ended field was included to provide an opportunity for participants to give additional feedback.

Data Analysis

QOL

Data from the QOL questionnaires were coded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0. Relevant descriptive statistics for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 questionnaires (EORTC, 1994, 1995) were calculated. Participants were divided into two treatment groups, chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy, to assess the association between treatment group and QOL. One-way analysis of variance and independent t tests (parametric tests) were used to test for association between variables. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used in all analyses.

Wellness Plan

Clinical and observational data from completed wellness plans were reviewed by the lead researcher (G.R.). Each BCS’s wellness plan was analyzed to identify issues experienced by participants, and the total number of documented issues for each BCS was recorded. To evaluate the ratio of metropolitan and rural participants, boundaries were defined as per the Australian Government (n.d.-b) Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry website. Wellness plans were analyzed collectively and then categorized into chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy cohorts to allow for comparison of issues reported.

Patient Satisfaction Survey

Quantitative data from the patient satisfaction survey were exported from SurveyMonkey into Microsoft Excel for analysis using descriptive statistics. Data were used to assess level of satisfaction, level of agreement, and type and number of all referrals generated. Data generated from open-ended responses were exported into NVivo, version 12.6.0, for analysis. Word frequency parameters were narrowed to the top 50 words and grouped with synonyms.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the study hospital’s human research ethics committee. An opt-out approach to consent was used; participants were included in the study unless they expressed that they wished to be excluded (Australian Government, n.d.-a).

Results

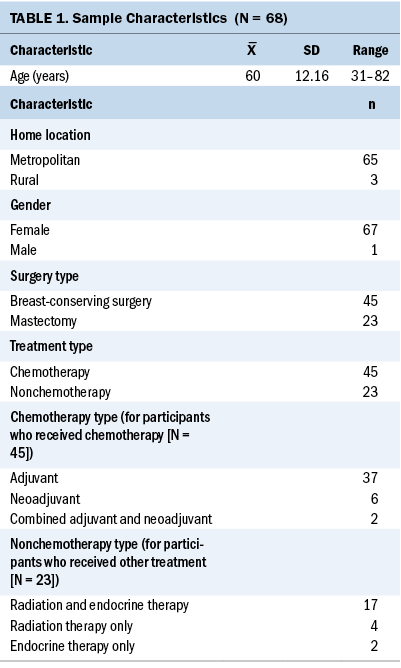

A total of 69 BCSs attended the WABCC during the nominated time period, and all attendees were invited to participate in the study. No potential participants opted out of the study. One BCS was excluded because of disease progression, resulting in a final sample of 68. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

QOL

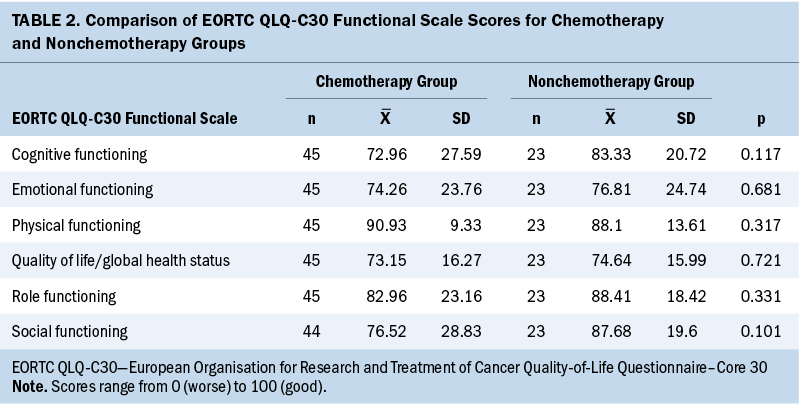

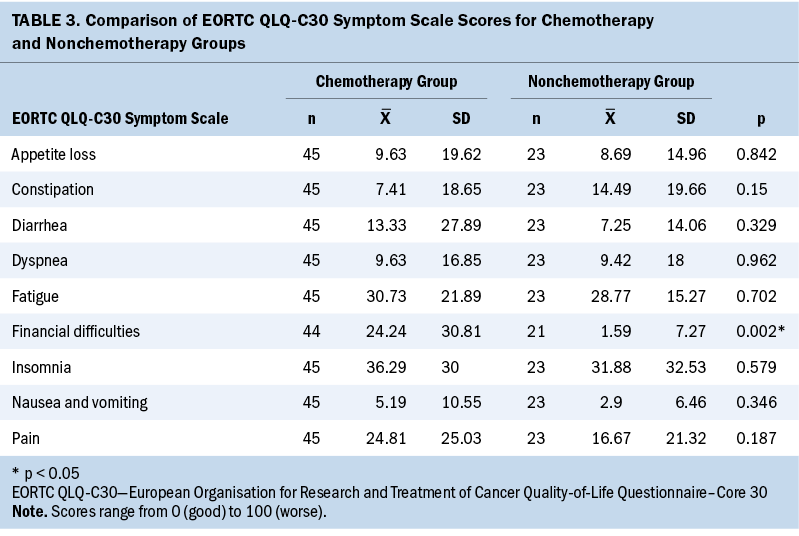

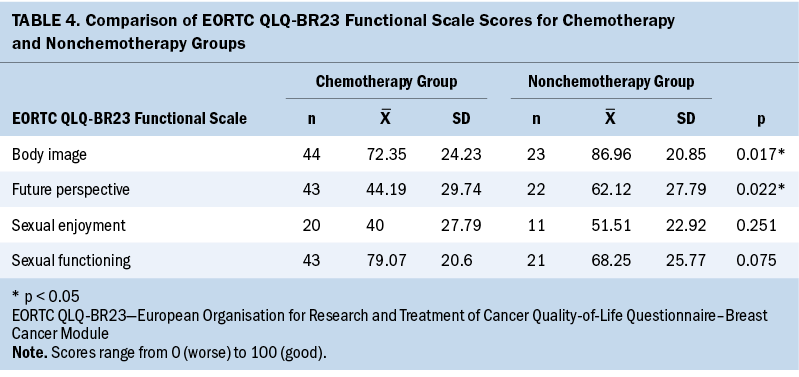

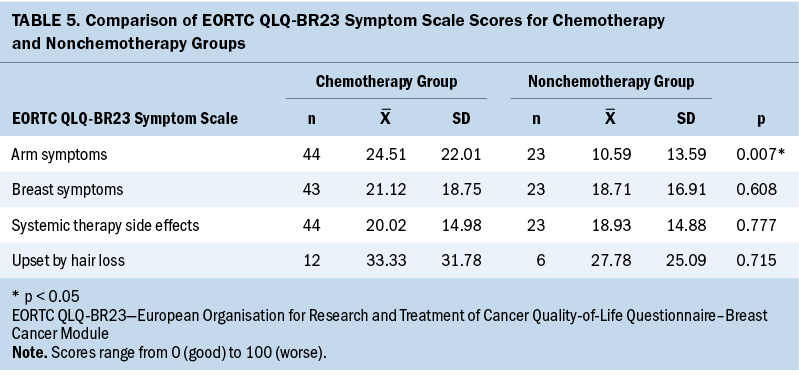

Sixty-eight participants completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. The QOL/global health status mean scores for both treatment groups were similar, and no statistically significant results were found in the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires for the chemotherapy or nonchemotherapy groups for any of the functional items (see Table 2). Analysis of the EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales found that financial difficulties were significantly higher for the chemotherapy group (p = 0.002) (see Table 3). The EORTC QLQ-BR23 functional scales showed that body image and future perspective were significantly lower in the chemotherapy group (p = 0.017 and p = 0.022, respectively) (see Table 4). On the EORTC QLQ-BR23 symptom scales, participants in the chemotherapy group had statistically significantly worse arm symptoms compared to the nonchemotherapy group (p = 0.007); no significant differences were found for other items included in the scale (see Table 5).

Wellness Plans

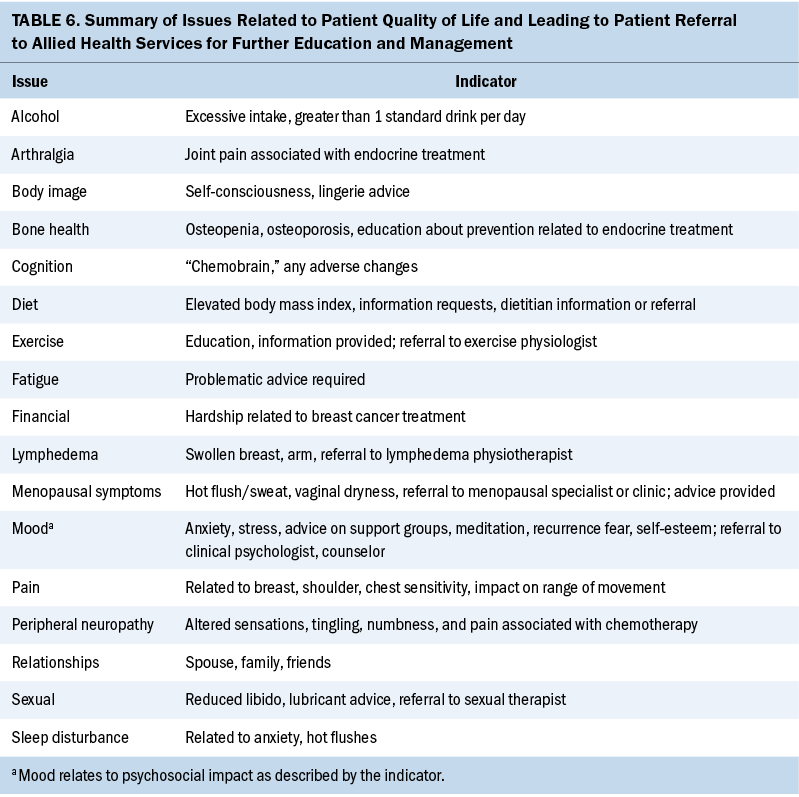

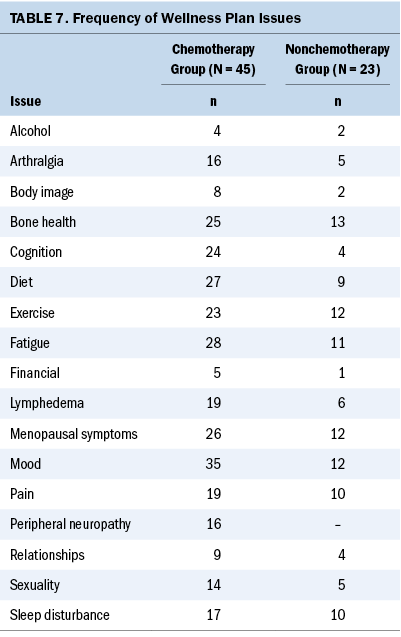

Wellness plans were assessed to describe the number of issues or symptoms of concern following completion of active breast cancer treatment. A total of 47 indicators were identified and categorized into 17 issues (see Table 6). The most frequently reported issues were problems with mood, followed by fatigue, menopausal symptoms, and bone health (see Table 7). The least reported issues were financial impact of breast cancer treatment and alcohol intake advice. Residual peripheral neuropathy was reported only in the chemotherapy group. Participants in the chemotherapy group had a mean of 7 issues with a range of 3–12. The most commonly reported issues were changes in mood, fatigue, and advice on diet. The least frequently reported issue was requiring education and advice on alcohol intake. In the nonchemotherapy group, participants reported a mean of five issues, with a range of two to nine. Education on bone health ranked as the highest issue requiring advice. Problems with mood changes, menopausal symptoms, and advice on exercise programs were equal in frequency, followed by fatigue. The least reported issue was financial impact of breast cancer treatment.

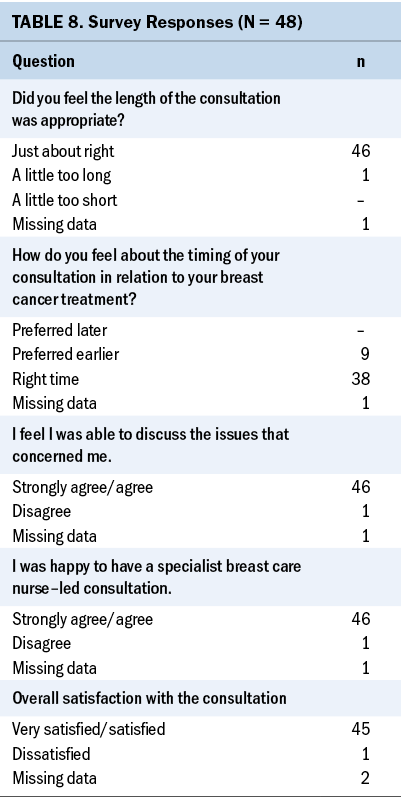

Patient Satisfaction Survey

A 70% (n = 48) response rate was obtained, and all responses were included in the analysis. There were high levels of satisfaction with timing and duration of consultation, and the ability to discuss issues of concern among survey respondents (see Table 8). A total of 69 referrals were disclosed by 40 participants; 8 participants did not respond to this question. The services most frequently referred to included lymphedema physiotherapist (n = 14, 20%), exercise programs (n = 14, 20%), corsetiere for bra/lingerie assistance (n = 11, 16%), and menopause specialist (n = 10, 15%). The least used referral service was the clinical psychologist (n = 4, 6%).

A total of 33 respondents provided additional comments at the end of the survey. The top five terms used by participants were “helpful,” “treatment,” “thank,” “well,” and “issues.” Participants reported that consultations were beneficial, their questions about treatments were answered, and support and information were provided. In addition, participants stated they had an opportunity to discuss issues that were recorded on their individualized wellness plan. Participants valued an individual consultation with an SBCN that allowed time to address concerns and activate resources. One participant described their consultation with the SBCN as “a valuable consult, which provided opportunities to discuss topics in depth. In today’s fast-paced life, an individual consult, which allows time to do this, is so rare. I can’t recommend these consults highly enough.”

Another participant described how the SBCN consultation provided guidance and direction following the completion of active treatment as follows: “Found this very beneficial and good to do after all active treatment finished. You can feel a little lost straight afterwards, and this gave you a bit of a plan moving forward.”

Most respondents felt they were given an opportunity to discuss their concerns and issues following their breast cancer treatment and appreciated referrals to allied health to address survivors’ concerns. One respondent stated:

I feel this is an essential part of the aftercare service. . . . It tied up loose ends or gives you time to address issues you didn’t feel [were] important at the time of treatment. . . . Aftercare was required because it included a new set of health issues because of [breast cancer] treatment that I left unattended because I felt like I’d been through enough. I felt like I could move on and open the door to the new normal with more enthusiasm and support.

The WABCC also provided an opportunity to debrief and address any fears affecting recovery. According to one participant,

I found this appointment to be vital to my moving on to a normal life. It was closure in a way. By summarizing the events of the past year, [the SBCN] enabled me to understand where I am and what I have to do to continue to move forward.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the issues BCSs experienced and to establish whether BCSs were satisfied with the SBCN-led WABCC. A wide range of issues were experienced by participants, including negative mood changes such as stress, anxiety, fear of recurrence, and physical issues such as fatigue and menopausal symptoms that concerned BCSs greatly and are consistent with other research findings (Iyer & Ring, 2017; Lisy et al., 2019; Vuksanovic et al., 2021). Symptoms such as fatigue, menopausal symptoms, bone health issues, pain, residual peripheral neuropathy, impaired cognitive function, hair loss, lymphedema, and sexual dysfunction can adversely affect BCSs’ emotional well-being (Iyer & Ring, 2017; Lisy et al., 2019). Identifying participants’ symptoms, providing education, and offering referrals to allied health aim to assist BCSs to live well.

Participants in this study had completed multimodal active treatments intended to control or cure breast cancer (All.Can, 2019), with the majority of participants receiving chemotherapy. Overall, participants’ QOL/global health status scores were similar for those in the chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy groups. However, the breast cancer–specific BR23 scale indicated that participants who received chemotherapy had worse arm symptoms, poorer body image, and lower future perspective scores. This supports growing evidence of the need to better understand the differences in survivorship issues experienced depending on treatment modalities (Ferreira et al., 2019). Lengths of active treatment are dependent on the treatment mode and may influence appropriate timing of clinic appointments. A small number of participants indicated a preference for earlier clinic appointments; it is likely these participants were in the nonchemotherapy group. Participants who do not receive chemotherapy have a shorter length of active treatment and are likely to benefit from earlier appointments. At commencement of endocrine treatment, the earlier identification and effective management of adverse effects, including education about the rationale for treatment, may contribute to increased adherence (Bender et al., 2014). Timing of a clinic appointment may need to be flexible to coincide with each individual’s treatment time frame.

The wellness plans demonstrated that although most participants reported concerns relating to recurrence, those who received chemotherapy were more likely to report more health-related issues. Those who received chemotherapy reported, on average, two more self-reported issues compared to participants in the nonchemotherapy group, further supporting evidence that patient needs are influenced by mode of treatment (Schmidt et al., 2022). Similar to other studies, the current authors found that fatigue was highly ranked for BCSs in the chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy groups (Jefford et al., 2016; Lisy et al., 2019; Meade et al., 2017). Fatigue is a common unmet physical need experienced by BCSs as a consequence of cancer treatment that limits usual activities. Therefore, education about the management of fatigue should be prioritized.

Financial burdens, including out-of-pocket expenses (medical and nonmedical) (Lisy et al., 2019) and costs associated with survivorship care, present a further hurdle to BCSs’ QOL after active cancer treatment (Halpern et al., 2015; Kwan et al., 2019). Although this study was conducted in a private, not-for-profit tertiary hospital where patients may be more affluent than patients receiving treatment in other healthcare settings, significant differences in participants’ self-reported financial difficulties were found between the chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy groups. Participants in the chemotherapy group were more likely to report financial difficulties than those in the nonchemotherapy group. This may be related to the higher prevalence of symptoms observed in the chemotherapy group, which, in turn, affected functional ability. The symptoms experienced by participants in the chemotherapy group and the resulting reduced functional ability may have impeded their capacity to work.

Of note, financial issues were the least documented issue in the wellness plans, even though individuals with breast cancer report financial hardship as an unmet need (Breast Cancer Network Australia, 2017; Lisy et al., 2019). BCSs who have relied on financial support from family or friends to pay for medical expenses or wellness programs may have experienced feelings of shame or stigma. Some participants had requested that this information not be documented in their wellness plan, resulting in underreporting. It is also likely that some participants may not have disclosed financial difficulties. Similarly, stigma around financial difficulties has been reported in young adult cancer survivors who expressed feelings of shame when resorting to crowdfunding for medical expenses (Ghazal et al., 2023).

Although issues with sexual health were self-reported in the QOL questionnaire, some participants declined further education or requested that the discussion not be documented in their wellness plan. Reluctance to discuss and report sexual dysfunction could be related to feelings of embarrassment, fear of negative judgment, or feeling grateful to be a BCS, with sexual health not being a priority. Providing an opportunity for open discussion on sexual health with assurance of an off-the-record conversation may facilitate communication on a sensitive issue, which otherwise may not occur. Patients may feel that inclusion of this information violates their privacy; therefore, there is a need for awareness of their preferences and sensitivities. This supports previous studies regarding the need to further understand BCSs’ barriers regarding discussion and education about sexual health (Canzona et al., 2019; Kingsberg et al., 2019).

The use of wellness plans that included a written summary of breast cancer diagnosis, treatment, and resources to assist with making healthy lifestyle choices was valued by participants. The absence of comprehensive summaries has previously been reported as an unmet need that contributed to BCSs feeling unsupported after active treatment (Meade et al., 2017). Recommendations report that a key responsibility of SBCNs in delivering survivorship care in a shared care situation is to provide education about healthy lifestyle choices that BCSs can control, including diet, exercise, and alcohol intake (Cancer Australia, 2020). BCS focus groups in Ireland similarly reported unmet needs around dietary advice, exercise, healthy lifestyle choices, and psychological support (Meade et al., 2017).

Self-reported QOL assessments and wellness plans are necessary for comprehensive and holistic assessments. Exploration of the experiences of participants reported in QOL assessments and education provided by the SBCN, including healthy lifestyle choices, management of and education about potential treatment side effects, and general health recommendations, provides an opportunity for issues that may not have been considered a priority by BCSs to be discussed and documented. This is further demonstrated in this study by the differences in self-reported QOL score and wellness plan issue frequency. For example, no statistically significant results were found in the QOL scores between the chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy groups for education about healthy diet and cognition changes experienced. However, more participants in the chemotherapy group required advice compared to the nonchemotherapy group in the wellness plans.

An SBCN-led WABCC provides continuity of care with an opportunity for participants to debrief and reflect on their cancer journey. Individuals with breast cancer treated at the study hospital had developed a relationship with the SBCN during their active treatment. Models of breast cancer survivorship care are varied, and “one size does not fit all” (Porter-Steele et al., 2017, p. 14); the current study found high levels of satisfaction with the SBCN-led WABCC. This supports the findings of other studies that found that BCSs value and feel comfortable with care provided by SBCNs (Brown et al., 2018; Post et al., 2017).

Limitations

The study was conducted at a single-site, private, not-for-profit tertiary hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other settings. The anonymous nature of the survey meant it was not possible to identify the treatment type of the participants completing the survey. The study sample consisted predominantly of BCSs who resided in metropolitan areas; the experiences and preferences of rural-based BCSs may differ. This study did not include patients with advanced and metastatic disease, who may have differing priorities and needs.

Implications for Nursing

BCSs report unmet needs as a consequence of their treatment, and the findings of this study indicate that these vary according to mode of treatment. Having an opportunity to attend a survivorship clinic as a routine appointment on completion of active treatment allows these needs to be assessed and addressed to improve QOL outcomes. SBCNs are integral along the active treatment continuum for individuals diagnosed with breast cancer and their significant others, and this crucial role extends into survivorship care. The support provided by SBCNs is holistic and extends beyond the physical impacts of cancer. All BCSs should be offered an SBCN-led, face-to-face consultation to provide an opportunity to promote healthy lifestyle choices and discuss issues not deemed a priority by BCSs’ self-assessment preconsultation. An individualized wellness plan that records BCSs’ issues and a treatment plan to facilitate open communication, aiming for optimal management of documented needs, should be developed and shared. This plan should be provided to the BCS and all healthcare providers involved in their care.

Conclusion

The SBCN-led survivorship clinic was satisfactory, appropriately timed, and helpful in providing participants with an opportunity to reflect on their breast cancer journey. This study provides further evidence that BCSs’ needs are influenced by the type of treatment received and suggests that appointments with the WABCC should be aligned with completion of active treatment. In addition, participants appreciated individualized wellness plans that documented their treatment and provided options to set achievable goals in making healthy lifestyle choices using evidence-based resources.

The current study also supports the findings from the European Society for Medical Oncology that cancer survivorship care includes physical and psychological effects of surveillance for cancer recurrence and general health promotion (Vaz-Luis et al., 2022). As the survival rate for breast cancer improves worldwide, not all BCSs have access to supportive survivorship care. Globally, the goals of survivorship care are focused on QOL, improved survival, and better overall physical, psychosocial, and long-term health (Halpern et al., 2016). The WABCC addresses issues related to breast cancer treatment and provides BCSs with the tools required to manage life after breast cancer.

About the Authors

Gay Refeld, BN, RN, is a clinical nurse consultant at St. John of God Subiaco Hospital in Western Australia; Christobel Saunders, AO, MBBS, FRACS, is the James Stewart Chair of Surgery in the Department of Surgery in the Centre for Medical Research at Royal Melbourne Hospital in the Melbourne Medical School at the University of Melbourne in Victoria, Australia; Niloufer Jahan Johansen, PhD, was, at the time of this writing, a research officer at St. John of God Subiaco Hospital; Elizabeth Sorial, MPH, is a research assistant in the School of Medicine at the University of Western Australia in Perth; and Alannah Louise Cooper, PhD, RN, is a nurse researcher at St. John of God Subiaco Hospital. No financial relationships to disclose. Refeld, Saunders, and Johansen contributed to the conceptualization and design. Refeld and Johansen completed the data collection. Johansen, Sorial, and Cooper provided statistical support and the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Refeld can be reached at gay.refeld@sjog.org.au, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2023. Accepted July 19, 2023.)

References

All.Can. (2019). Patients insights on cancer care: Opportunities for improving efficiency. https://www.all-can.org/publications/patient-insights-on-cancer-care-op…

Australian Government. (n.d.-a). National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007 (updated 2018). National Health and Medical Research Council. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethic…

Australian Government. (n.d.-b). Postcode delivery classifications. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. https://www.agriculture.gov.au/biosecurity-trade/import/online-services…

Bender, C.M., Gentry, A.L., Brufsky, A.M., Casillo, F.E., Cohen, S.M., Dailey, M.M., . . . Sereika, S.M. (2014). Influence of patient and treatment factors on adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(3), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.274-285

Breast Cancer Network Australia. (2017). The financial impact of breast cancer. https://www.bcna.org.au/about-us/policy-advocacy/research-reports/the-f…

Breast Cancer Trials. (n.d.). Understanding breast cancer statistics and survival rates. https://www.breastcancertrials.org.au/understanding-breast-cancer-stati…

Brédart, A., Merdy, O., Sigal-Zafrani, B., Fiszer, C., Dolbeault, S., & Hardouin, J.-B. (2016). Identifying trajectory clusters in breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs, psychosocial difficulties, and resources from the completion of primary treatment to 8 months later. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(1), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2799-1

Brennan, M., Butow, P., Spillane, A., & Boyle, F. (2008). Survivorship care after breast cancer. Australian Family Physician, 37(10), 826–830.

Brown, J., Refeld, G., & Cooper, A. (2018). Timing and mode of breast care nurse consultation from the patient’s perspective. Oncology Nursing Forum, 45(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.ONF.389-398

Cancer Australia. (2020). Roles and responsibilities of the shared follow-up and survivorship care team. https://bit.ly/3ZkvtjU

Canzona, M.R., Fisher, C.L., Wright, K.B., & Ledford, C.J.W. (2019). Talking about sexual health during survivorship: Understanding what shapes breast cancer survivors’ willingness to communicate with providers. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 13(6), 932–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00809-2

Clinical Oncology Society of Australia. (2016). Model of survivorship care: Critical components of cancer survivorship care in Australia [Position statement, v.1.0]. https://www.cosa.org.au/media/332340/cosa-model-of-survivorship-care-fu…

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. (1994). EORTC QLQ—BR23. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/Specimen-BR23-English…

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. (1995). EORTC QLQ—C30 [v.3.0]. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/Specimen-QLQ-C30-Engl…

Ferreira, A.R., Di Meglio, A., Pistilli, B., Gbenou, A.S., El-Mouhebb, M., Dauchy, S., . . . Vaz-Luis, I. (2019). Differential impact of endocrine therapy and chemotherapy on quality of life of breast cancer survivors: A prospective patient-reported outcomes analysis. Annals of Oncology, 30(11), 1784–1795. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz298

Finlayson, T.L., Moyer, C.A., & Sonnad, S.S. (2004). Assessing symptoms, disease severity, and quality of life in the clinical context: A theoretical framework. American Journal of Managed Care, 10(5), 336–344.

Gast, K.C., Allen, S.V., Ruddy, K.J., & Haddad, T.C. (2017). Novel approaches to support breast cancer survivorship care models. Breast, 36, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.08.004

Ghazal, L.V., Watson, S.E., Gentry, B., & Santacroce, S.J. (2023). “Both a life saver and totally shameful”: Young adult cancer survivors’ perceptions of medical crowdfunding. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 17(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01188-x

Halpern, M.T., McCabe, M.S., & Burg, M.A. (2016). The cancer survivorship journey: Models of care, disparities, barriers, and future directions. American Society of Clinical Oncology Education Book, 35, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_156039

Halpern, M.T., Viswanathan, M., Evans, T.S., Birken, S.A., Basch, E., & Mayer, D.K. (2015). Models of cancer survivorship care: Overview and summary of current evidence. Journal of Oncology Practice, 11(1), e19–e27. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2014.001403

Iyer, R., & Ring, A. (2017). Breast cancer survivorship: Key issues and priorities of care. British Journal of General Practice, 67(656), 140–141. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X689845

Jefford, M., Gough, K., Drosdowsky, A., Russell, L., Aranda, S., Butow, P., . . . Schofield, P. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led supportive care package (SurvivorCare) for survivors of colorectal cancer. Oncologist, 21(8), 1014–1023. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0533

Kingsberg, S.A., Schaffir, J., Faught, B.M., Pinkerton, J.V., Parish, S.J., Iglesia, C.B., . . . Simon, J.A. (2019). Female sexual health: Barriers to optimal outcomes and a roadmap for improved patient-clinician communications. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(4), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7352

Kozul, C., Stafford, L., Little, R., Bousman, C., Park, A., Shanahan, K., & Mann, G.B. (2020). Breast cancer survivor symptoms: A comparison of physicians’ consultation records and nurse-led survivorship care plans. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 24(3), E34–E42. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.CJON.E34-E42

Kwan, J.Y.Y., Croke, J., Panzarella, T., Ubhi, K., Fyles, A., Koch, A., . . . Bender, J.L. (2019). Personalizing post-treatment cancer care: A cross-sectional survey of the needs and preferences of well survivors of breast cancer. Current Oncology, 26(2), e138–e146. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.4131

Lisy, K., Langdon, L., Piper, A., & Jefford, M. (2019). Identifying the most prevalent unmet needs of cancer survivors in Australia: A systematic review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15(5), e68–e78. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13176

Meade, E., McIlfatrick, S., Groarke, A.M., Butler, E., & Dowling, M. (2017). Survivorship care for postmenopausal breast cancer patients in Ireland: What do women want? European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 28, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2017.03.003

Nguyen, J., Popovic, M., Chow, E., Cella, D., Beaumont, J.L., Chu, D., . . . Bottomley, A. (2015). EORTC QLQ-BR23 and FACT-B for the assessment of quality of life in patients with breast cancer: A literature review. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 4(2),157–166. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.76

Peate, M., Saunders, C., Cohen, P., & Hickey, M. (2021). Who is managing menopausal symptoms, sexual problems, mood and sleep disturbance after breast cancer and is it working? Findings from a large community-based survey of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 187(2), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06117-7

Porter-Steele, J., Tjondronegoro, D., Seib, C., Young, L., & Anderson, D. (2017). ‘Not one size fits all’: A brief review of models of care for women with breast cancer in Australia. Cancer Forum, 41(1), 13–19. https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/bitstream/handle/10072/3902…

Post, K.E., Moy, B., Furlani, C., Strand, E., Flanagan, J., & Peppercorn, J.M. (2017). Survivorship model of care: Development and implementation of a nurse practitioner-led intervention for patients with breast cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(4), E99–E105. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.CJON.E99-E105

Radhakrishnan, A., Li, Y., Furgal, A.K.C., Hamilton, A.S., Ward, K.C., Jagsi, R., . . . Wallner, L.P. (2019). Provider involvement in care during initial cancer treatment and patient preferences for provider roles after initial treatment. Journal of Oncology Practice, 15(4), e328–e337. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.18.00497

Saltbæk, L., Karlsen, R.V., Bidstrup, P.E., Høeg, B.L., Zoffmann, V., Horsbøl, T.A., . . . Johansen, C. (2019). MyHealth: Specialist nurse-led follow-up in breast cancer. A randomized controlled trial—Development and feasibility. Acta Oncologica, 58(5), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2018.1563717

Schmidt, M.E., Goldschmidt, S., Hermann, S., & Steindorf, K. (2022). Late effects, long-term problems and unmet needs of cancer survivors. International Journal of Cancer, 151(8), 1280–1290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34152

Tan, M.L., Idris, D.B., Teo, L.W., Loh, S.Y., Seow, G.C., Chia, Y.Y., & Tin, A.S. (2014). Validation of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires in the measurement of quality of life of breast cancer patients in Singapore. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 1(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.135817

Vaz-Luis, I., Masiero, M., Cavaletti, G., Cervantes, A., Chlebowski, R.T., Curigliano, G., . . . Pravettoni, G. (2022). ESMO expert consensus statements on cancer survivorship: Promoting high-quality survivorship care and research in Europe. Annals of Oncology, 33(11), 1119–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.1941

von Elm, E., Altman, D.G., Egger, M., Pocock, S.J., Gøtzsche, P.C., & Vandenbroucke, J.P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLOS Medicine, 4(10), e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

Vuksanovic, D., Sanmugarajah, J., Lunn, D., Sawhney, R., Eu, K., & Liang, R. (2021). Unmet needs in breast cancer survivors are common, and multidisciplinary care is underutilised: The survivorship needs assessment project. Breast Cancer, 28(2), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01156-2