Addressing Cultural Competency: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Cancer Care

Background: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals face mental and physical health disparities. Fear of discrimination and organizational care incompetency promotes avoidance of care and nondisclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity.

Objectives: The purpose of this article is to evaluate the outcomes of cultural competency training for interprofessional staff to foster safe and inclusive LGBTQ cancer care and address this population’s care needs.

Methods: One-hour cultural competency training focused on assessing bias, increasing health knowledge, and creating a safe environment. Fifteen sessions trained 110 participants. Pre- and post-training surveys evaluated staff’s LGBTQ health knowledge and cultural competency self-efficacy.

Findings: Staff were significantly more likely to agree with the following statements post-training: “Organizations should make their bathrooms accessible to gender-variant patients/families and staff,” “I am likely to intervene in a homophobic interaction at work,” “I am confident in asking gender identity questions that are appropriate to my job,” and “I am confident in my ability to provide appropriate LGBTQ resources for my patients.”

Jump to a section

Earn free contact hours: Click here to connect to the evaluation. Certified nurses can claim no more than 1.0 total ILNA point for this program. Up to 1.0 ILNA point may be applied to Professional Practice/Performance. See www.oncc.org for complete details on certification.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals make up 4.5% of the U.S. population, or roughly 11 million people (Conron & Goldberg, 2020). National healthcare organizations, including the Joint Commission, Institute of Medicine (IOM), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, recognize the need for actionable strategies to reduce health disparities for sexual and gender minorities (SGMs) (Griggs et al., 2017; IOM, 2011; Joint Commission, 2014; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017). The LGBTQ population is composed of diverse communities, but they share a common burden of higher rates of smoking, alcohol use, substance use disorder, anxiety, and depression (IOM, 2011; Joint Commission, 2014; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017). Certain health disparities found in LGBTQ patients with cancer stem from these shared issues. In addition, there are risks that are individual to separate communities within the LGBTQ population. For example, men who have sex with men are at higher risk for human papillomavirus and HIV transmission, lesbian and bisexual women (those assigned female at birth) have higher rates of obesity and nulliparity, lesbians are less likely to get preventive screening for cervical cancer, and transgender individuals are less likely to have health insurance (Tamargo et al., 2017). These disparities create an increased risk of anal, lung, breast, ovarian, and cervical cancer. Healthcare experience disparities also contribute to worse health outcomes (Griggs et al., 2017; Hudson & Donohue, 2019; Hulbert et al., 2017; IOM, 2011; Joint Commission, 2014).

Suboptimal LGBTQ care stems from lack of healthcare team training in caring for LGBTQ-specific health needs, lack of opportunities for SGMs to safely disclose sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), discrimination, marginalization, and the fear of discrimination (Griggs et al., 2017). LGBTQ individuals still experience denial of care, negative attitudes and behavior, exclusion from traditional cancer screening campaigns, and implicit bias that leads to avoidance of the healthcare setting. Early cancer detection, survivorship care planning, patient–provider communication, and quality of care suffer from intentional and unintentional marginalization of the LGBTQ community (Griggs et al., 2017; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017). The increased incidence of health disparities within minority communities is recognized within the health community, and it is imperative that healthcare providers address this.

Minority stress theory is one lens in which this relationship is better understood. The minority stress theory states that individuals who come from a stigmatized minority position face adverse effects, or stress, of alienation from dominant social institutions (Meyer, 2003; Rice, 2019). The link between identity and stress are consequential. Intersectionality is a complex term but, simply defined, is the facets of an individual’s identity that diverge and interact throughout that individual’s life (Margolies & Brown, 2019). LGBTQ patients bring their race, education, employment, relationship status, religion, and a myriad of other identities in with them to the healthcare setting. Although these patients may fall under the LGBTQ umbrella, their other identities may create more pressing barriers or compound existing barriers to optimal health outcomes. Considering the intersection of identities helps to shed light on barriers to care (Kamen et al., 2019).

Workforce cultural competency development is a key strategy to addressing LGBTQ barriers to care. ASCO endorses expanding and promoting cultural competency training tailored to the cancer setting for all healthcare team members. There are many definitions and understandings of cultural competency; a comprehensive definition comes from the National Center for Cultural Competence, which states that cultural competency occurs at an individual and system level when there is a defined set of values and principles that demonstrate behaviors, attitudes, policies, and structures that enable them to work effectively cross-culturally (Radix & Maingi, 2018). Healthcare workers must obtain the skills and principles to value diversity and assess their own intersectional cultural values. They must use these skills to integrate cultural knowledge into practice and adapt care to the cultural context of individuals and communities served (Margolies & Brown, 2019). All healthcare team members need LGBTQ cultural competency training because patients encounter an interprofessional team across the care continuum (Griggs et al., 2017). Healthcare professionals receive this training with the goal of providing high-quality care and addressing existing gaps in care that contribute to LGBTQ health disparities.

The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Healthcare Equality Index is a national benchmarking tool for policies and practices related to equity and inclusion of LGBTQ patients, visitors, and employees. Although many healthcare facilities work to promote LGBTQ patient–centered care, HRC (2020) still reports that 56% of lesbian, gay, and bisexual patients and 70% of transgender patients experience some type of discrimination in health care. Research recommends that healthcare facilities provide access to LGBTQ-specific cultural competency, responsiveness, and humility training for all cancer team members, provide a safe environment for disclosure by using LGBTQ-inclusive language, and ask about and use patients’ correct names and pronouns (Kamen et al., 2019). This recommendation reinforces ASCO LGBTQ care position statements and seminal work presented by IOM and the Joint Commission.

The University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore, Maryland, conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to promote culturally competent cancer care for the LGBTQ population. The primary goal of this QI project was to evaluate the outcomes of cultural competency training. Specifically, this project aimed to educate staff about components of SOGI, why LGBTQ patients avoid health care, health disparities affecting LGBTQ patients, and ways to foster a safe and inclusive environment for LGBTQ patients and address this population’s care needs.

Methods

This QI project used a Plan-Do-Study-Act design. Four one-hour planning meetings were held by an interprofessional work group consisting of an inpatient RN, a registered nurse navigator, a licensed social worker, and an adolescent and young adult patient navigator. A gap in the practical application of cultural competency values and skills was noted in everyday care provided by frontline workers. The project team met with the goal of generating a formal, evidence-based, and oncology-tailored cultural competency training that was appropriate for staff members with direct patient contact at the comprehensive cancer center. Executive leadership gave their support and funding for the National LGBT Cancer Network’s (http://cancer-network.org) cultural competency training program. The training provided a toolkit and evaluation measures that were created with the purpose of being modifiable for any organization to assess learning outcomes. Fifteen cancer center champions were then recruited to participate in the National LGBT Cancer Network’s cultural competency program, with the goal of disseminating cultural competency training. The training was an eight-hour, nationally recognized, culturally competent training session that aimed to improve cancer care for the LGBTQ community by training healthcare providers. The champions consisted of social workers, a physician, a nurse practitioner, a dietitian, clinical research staff, and nurses from various sections of the cancer center, including inpatient and outpatient. On champion training completion, the team met multiple times to collaborate and develop customized presentation material and scripting to ensure that all champions were teaching the same content. Resources and best practices from local LGBTQ health resource centers, such as Chase Brexton Health Care Center for LGBTQ Health Equity, HRC’s Healthcare Equality Index Resource Guide, and fundamental LGBTQ health literature, such as The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding from IOM (2011), were also used not only to provide thorough and expansive material, but also to provide additional resources for training participants. The training and meeting date and time were set with champions’ input to minimize routine work interruption.

Sample and Setting

The cancer center is part of a large academic institution with 48 dedicated inpatient beds and a 35-bay oncology infusion center for treatment and management of transplantation and cellular therapies, solid tumors, and hematologic malignancies. The cancer center sees more than 3,000 new patients with cancer annually and participates in 218 clinical trials. During a period of five weeks, from January through February 2020, 110 attendees received cultural competency training. Each session had a diverse group of attendees from all areas of the cancer center, including inpatient, ambulatory, radiation oncology, and research. Training session size was limited to less than 15 participants. Profession and work area of participants are as follows: 62 staff RNs; 2 survivorship nurse navigators; 9 medical assist staff, including radiation therapy technicians, medical assistants, and patient care technicians; 6 clerical staff; 3 administrative staff; 2 patient liasons; 6 medical students; 8 social workers; 5 physicians; 4 nurse practitioners; and 3 physician assistants.

Intervention

The training program included videos, interactive exercises, and class discussion focused on assessing bias, increasing health knowledge, creating a safe environment, and adapting to LGBTQ health needs. LGBTQ terms were discussed briefly, and emphasis was placed on allowing and encouraging patient self-identification and open communication. Champions gave statistics on cancer and other health disparities and statistics detailing the limited number of cancer centers that collect SOGI information or use gender-neutral pronouns on intake forms. Interactional activities focused on how it feels to be “other” in race, age, disability, health, and other contexts. Videos of real-life and simulated LGBTQ patient experiences of discrimination and bias in the healthcare system were shown. Multilayered experiences of discrimination and intersectionality were discussed. This included discussing interpersonal microaggressions, such as heteronormative or gender cultural assumptions or language and intrapersonal fear of marginalization of self and support systems. Systemic discrimination was described. Participants were challenged to become aware of their own biases and actions that may promote unintentional marginalization toward those of different backgrounds. This included exercises to identify commonly made assumptions about individuals’ SOGI and how these assumptions interfere with building trust and rapport with patients (Joint Commission, 2014). The difference between equality and equity was explored. Emphasis was placed on the need to provide support and resources tailored to individual needs compared to a “treat everyone the same” approach in pursuit of reaching quality treatment and outcomes for all patients. Best practices in patient interaction were discussed, including incorporating SOGI disclosure into routine practice at appropriate times. The training stressed using nongendered terms or asking patient preference as standard of care, particularly when referring to gendered body parts, patients’ and loved ones’ titles and relationships, and pronouns. Additional online resources through the HRC Healthcare Equality Index Resource Guide and the National LGBT Cancer Network’s webpage specifically for LGBT patients with cancer (https://cancer-network.org), including smoking cessation campaigns and best practices for asking about SOGI, were shared with participants.

Training Procedures

The interprofessional champion workgroup planned 15 one-hour sessions on multiple days at various times to ensure that cancer center team members on all shifts could attend. Executive leadership encouraged attendance by all interprofessional cancer center team members, and continuing education credits were provided to recognize the time commitment of attending voluntary sessions. At least two champions presented at each session, and champions’ roles during training varied as sections of training were switched to ensure flexibility.

Data Collection

Participants completed a six-item Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), originating from National LGBT Cancer Network training but tailored to the facility’s needs, prior to and after each training session. The surveys were coded to preserve anonymity but enable tracking of individuals’ results. Four items assessed staff attitude toward LGBTQ individuals and the healthcare environment relevant to LGBTQ individuals; two items assessed staff confidence in providing care for LGBTQ patients. These items are a level 2 on the Kirkpatrick Model assessing participants’ change in intention, attitude, and self-efficacy for enacting skills and knowledge (Margolies et al., 2017). The items were designed exclusively for objectives and information presented in this training.

Data Analysis

Using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25.0, a paired-samples t test to evaluate the impact of the training session on team members’ LGBTQ cultural competence scores was completed. A p value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

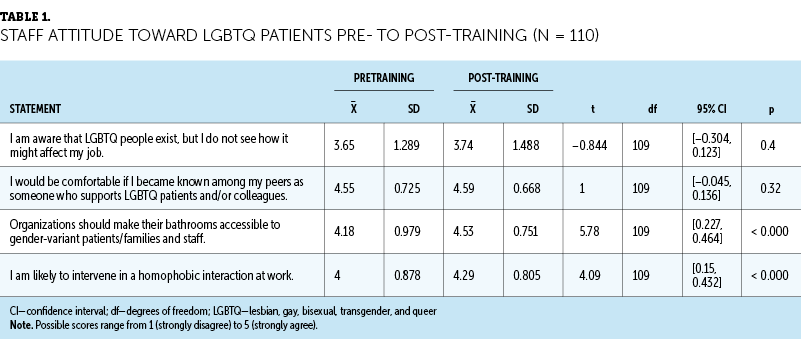

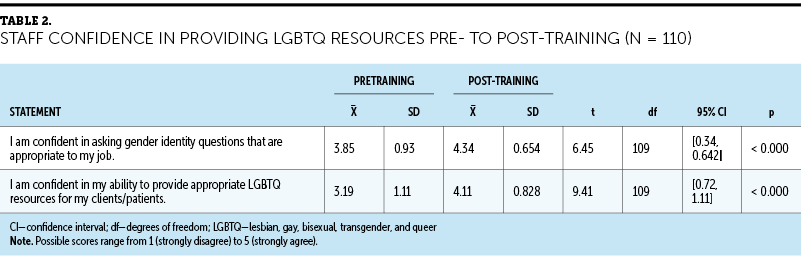

There were statistically significant improvements in survey scores from items related to staff attitude toward LGBTQ patients and staff confidence in providing LGBTQ resources from pre- to post-training. Tables 1 and 2 detail the t-test results.

Staff Attitudes

Staff were significantly more likely to agree with the statement, “Organizations should make their bathrooms accessible to gender-variant patients/families and staff,” from pre- (mean = 4.18, SD = 0.979) to post-training (mean = 4.53, SD = 0.751) (t[109] = 5.78, p < 0.000 [two-tailed]). The mean improvement in bathroom accessibility question scores was 0.345, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 0.464 to 0.227. The eta-squared statistic (0.23) indicated a large effect size. Staff were significantly more likely to agree with the statement, “I am likely to intervene in a homophobic interaction at work,” pre- (mean = 4, SD = 0.878) to post-training (mean = 4.29, SD = 0.805) (t[109] = 4.09, p < 0.000 [two-tailed]). The mean improvement in the intervention with homophobic interaction question scores was 0.29, with a 95% CI ranging from 0.432 to 0.15. No statistical difference was found for the remaining two questions.

Staff LGBTQ Resource Confidence

Staff were significantly more likely to agree with the statement, “I am confident in asking gender identity questions that are appropriate to my job,” pre- (mean = 3.85, SD = 0.93) to post-training (mean = 4.34, SD = 0.654) (t[109] = 6.45, p < 0.000 [two-tailed]). The mean improvement in confidence in asking gender identity question scores was 0.49, with a 95% CI ranging from 0.642 to 0.34. Staff were significantly more likely to agree with the statement, “I am confident in my ability to provide appropriate LGBTQ resources for my clients/patients,” pre- (mean = 3.19, SD = 1.11) to post-training (mean = 4.11, SD = 0.828) (t[109] = 9.41, p < 0.000 [two-tailed]). The mean improvement in providing appropriate LGBTQ resources question scores was 0.92, with a 95% CI ranging from 1.11 to 0.72.

Discussion

This oncology-tailored LGBTQ cultural competency training enhanced team members’ attitudes toward LGBTQ patients and enhanced LGBTQ health knowledge self-efficacy. In pre- and post-training scores, the majority of staff stated that they were comfortable being known as someone who was supportive of LGBTQ people and, consequently, no statistically significant change was found for this item. These findings suggest that healthcare staff are open to the needs of a culturally diverse patient population but need training to direct them on the skills and strategies to build a safe and welcoming environment for LGBTQ individuals and that a comprehensive cultural competency program can help to address the well-documented continuing intentional and unintentional discrimination of LGBTQ individuals in healthcare settings. The QI project findings suggest that successfully addressing sensitive topics, such as homophobia and bias, is best achieved in small, interactive groups. Institutional and individual changes are needed to address workforce cultural incompetence that contributes to health disparities. Institutional practices, such as posting nondiscrimination policies, diverse visual representation, and routine SOGI data collection, were emphasized in training as critical to a culturally competent system (Griggs et al., 2017; IOM, 2011; Margolies & Brown, 2019; Radix & Maingi, 2018).

Given the increase in participants’ confidence in asking gender identity–appropriate questions, the QI project outcomes support providing competency training that directly gives resources and practical tips for speaking with LGBTQ individuals. This includes an emphasis on open communication, nongendered terms and phrases, nonjudgmental mannerisms, and seeing the patient as a whole person (Margolies & Brown, 2019). Providing staff with resources for specific LGBTQ health needs is important to increasing staff’s confidence in providing care to this patient population. Tobacco cessation is a specific topic that affects LGBTQ cancer disparities (IOM, 2011; Joint Commission, 2014; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017). A significant improvement in care confidence was achieved when staff were educated about a specific disparity, such as tobacco use, and the resources to help patients with those health issues. This approach with direct knowledge and resources to help staff care for the LGBTQ patient population’s needs is crucial to successful cultural competency training.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge several limitations to this project, including the use of convenience sampling, use of a questionnaire survey format, and application in one comprehensive cancer center. The current project was not intended to be generalizable; however, the survey was designed explicitly for this training. Participants reported misunderstanding of the item, “I am aware that LGBTQ people exist, but I do not see how it might affect my job.” This item will be reworded for future study to include only one factor, such as “I understand how cultural competency training affects my job.” Limited valid and reliable evaluation tools are available to assess LGBTQ health knowledge self-efficacy and attitude toward LGBTQ patients. Valid and reliable tools will be used for future outcome measurements if made available. Although this training was voluntary, national authorities, such as IOM and ASCO, support integrating mandatory training for all healthcare staff. Given the demands of a high-acuity, large academic medical center, there are many competing priorities for healthcare professionals’ limited time and scheduling demands. Participation by more than 100 cancer center team members was only achieved because of prioritization from leadership and employee interest in this topic. The National LGBT Cancer Network (2022) will be releasing a new online cultural competency training program in 2022 for providers and other medical staff with a special lens on cancer in lieu of in-person cultural competency training.

Implications for Nursing

This QI project illustrates an accessible, effective, and comprehensive approach to LGBTQ cultural competency training applicable to all disciplines with direct interaction with patients with cancer. This interprofessional approach is key to developing a more culturally competent healthcare system (Griggs et al., 2017; IOM, 2011). Using widely available resources from national authorities, such as HRC, the Joint Commission, IOM, and the National LGBT Cancer Network, is pivotal in ensuring the most up-to-date best practices. Interactional activities to increase understanding of complex issues, such as microaggressions and unintentional bias, provide opportunity to fully engage staff in developing skills needed to provide culturally competent care.

LGBTQ patients must feel safe to disclose their SOGI, and it is the responsibility of the healthcare environment to give patients a safe and easy way to disclose this information (Kamen et al., 2019; Margolies & Brown, 2019; Radix & Maingi, 2018; Wheldon et al., 2018). Collection of SOGI data is not only important for individual care, but healthcare organizations, such as ASCO, the Joint Commission, and IOM, stress the importance of systemic improvement in SOGI data collection to help decrease LGBTQ health disparities (Griggs et al., 2017; IOM, 2011; Joint Commission, 2014). Teaching staff to provide for appropriate confidential SOGI disclosure is important in LGBTQ patient care (Kamen et al., 2019).

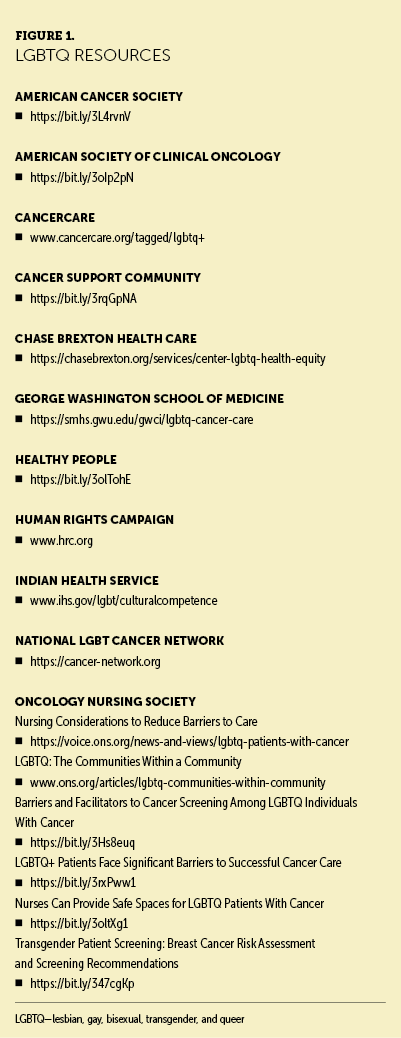

Enabling staff to provide tailored resources is part of workforce development. Resources developed for the SGM community, including health and wellness, provide expanded education on community-specific health needs. A list of additional LGBTQ resources is listed in Figure 1. Linking patients to care and information that is needed is emphasized in training. ASCO emphasizes making support services more widely available to SGMs (Griggs et al., 2017).

Conclusion

A culturally incompetent healthcare workforce contributes to LGBTQ health disparities. Cultural competency tailored to the oncology population for all levels of healthcare staff is vital to addressing these disparities. Education on the components of SOGI, intentional and unintentional bias, health disparities, and strategies and tips to create an inclusive environment for LGBTQ patients are main components of LGBTQ cultural competency training. Training needs to be completed by all staff who come in contact with patients.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Tracy Douglas, DNP, RN, BMTCN®, and Jenni Day, PhD, RN, for assistance with statistical analysis and manuscript review. They acknowledge the following champion trainers who participated in the National LGBT Cancer Network training and helped to organize this ongoing initiative: Brady Freitas, MSW, LCSW-C, Katherine Arensmeyer, MSN, ANP-BC, AOCNP®, Christina Boord, DNP, AGPCNP-BC, Mylene De Vera, MSN, RN, BMTCN®, Ashley Loftice, BSN, RN, OCN®, Kaitlin Schotz, RD, LDN, CSO, Megan Solinger, MHS, MA, OPN-CG, and Rachael Tavik, BSN, RN, OCN®.

About the Author(s)

Stephanie Russell, BSN, RN, OCN®, is a senior clinical nurse II and Nancy Corbitt, BSN, RN, OCN®, is a senior clinical nurse II and an oncology nurse navigator, both at the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center in Baltimore. The authors take full responsibility for this content. Funding for this initiative was provided by Kevin Cullen, MD, Suzanne Cowperthwaite, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, and the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center leadership. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Russell can be reached at stephanie.russell@umm.edu, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2021. Accepted January 1, 2022.)

References

Conron, K.J., & Goldberg, S.K. (2020). Adult LGBT population in the United States. UCLA Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/adult-lgbt-pop-us

Griggs, J., Maingi, S., Blinder, V., Denduluri, N., Khorana, A.A., Norton, L., . . . Rowland, J.H. (2017). American Society of Clinical Oncology Position Statement: Strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(19), 2203–2208. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441

Hudson, S., & Donohue, C. (2019). Cervical and anal cancer prevention for the LGBTQ population. Family Doctor, 7(3), 42–45.

Hulbert, W.N.J., Plumpton, C.O., Flowers, P., McHugh, R., Neal, R.D., Semlyen, J., & Storey, L. (2017). The cancer care experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual patients: A secondary analysis of data from the UK Cancer Patient Experience Survey. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(4), e12670. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12670

Human Rights Campaign. (2020). Healthcare equality index. https://reports.hrc.org/healthcare-equality-index-2020?_ga=2.248964295…

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. National Academies Press.

Joint Commission. (2014). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide.pdf

Kamen, C.S., Alpert, A., Margolies, L., Griggs, J.J., Darbes, L., Smith-Stoner, M., . . . Scout, N. (2019). “Treat us with dignity”: A qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(7), 2525–2532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4535-0

Margolies, L., & Brown, C.G. (2019). Increasing cultural competence with LGBTQ patients. Nursing, 49(6), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000558088.77604.24

Margolies, L., Joo, R., & McDavid, J. (2017). Best practices in creating and delivering LGBTQ cultural competency trainings for health and social service agencies. National LGBT Cancer Network. https://cancer-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/best_practices.pdf

Meyer, I.H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

National LGBT Cancer Network. (2022). Cultural competency training. https://bit.ly/344QqXS

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). LGBT. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/…

Radix, A., & Maingi, S. (2018). LGBT cultural competence and interventions to help oncology nurses and other health care providers. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.005

Rice, D. (2019). LGBTQ: The communities within a community. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23(6), 668–671. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.668-671

Romanelli, M., & Hudson, K.D. (2017). Individual and systemic barriers to health care: Perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(6), 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000306

Tamargo, C.L., Quinn, G.P., Sanchez, J.A., & Schabath, M.B. (2017). Cancer and the LGBTQ population: Quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers’ survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 6(10), 93.

Wheldon, C.W., Schabath, M.B., Hudson, J., Bowman Curci, M., Kanetsky, P.A., Vadaparampil, S.T., . . . Quinn, G.P. (2018). Culturally competent care for sexual and gender minority patients at National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers. LGBT Health, 5(3), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0217 [[[JOURNALCLUB]]]